Bacillus cereus is a spore-forming bacterium commonly associated with foodborne illnesses, and its spores are known for their remarkable resistance to harsh environmental conditions. However, the question of whether *Bacillus cereus* spores are heat labile is crucial in understanding their survival during food processing and cooking. While these spores can withstand high temperatures, they are not entirely heat-resistant; prolonged exposure to temperatures above 121°C (250°F) under pressure, such as in autoclaving, can effectively destroy them. Nonetheless, shorter exposure to lower temperatures, such as those used in typical cooking methods, may not always eliminate the spores, posing a potential risk of contamination if food is mishandled or stored improperly. This highlights the importance of proper food handling and processing techniques to mitigate the risk of *Bacillus cereus* spore survival and subsequent germination, which can lead to food spoilage and illness.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Heat Resistance Mechanisms: How B. cereus spores withstand or succumb to high temperatures during food processing

- Thermal Inactivation Kinetics: Studying the rate of spore destruction at varying heat levels

- Food Processing Impact: Effects of pasteurization, sterilization, and cooking on spore viability

- Strain Variability: Differences in heat sensitivity among B. cereus strains and their spores

- Survival in Heat-Treated Foods: Persistence of spores in processed foods despite thermal treatments

Heat Resistance Mechanisms: How B. cereus spores withstand or succumb to high temperatures during food processing

Bacillus cereus spores are notorious for their resilience, particularly in food processing environments where high temperatures are employed to eliminate pathogens. Despite being subjected to heat treatments that would destroy many other microorganisms, B. cereus spores often survive, posing a significant food safety risk. This survival is not due to chance but to a suite of sophisticated heat resistance mechanisms that these spores employ. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing effective strategies to control B. cereus in food products.

One key mechanism of heat resistance in B. cereus spores is their unique structure. The spore’s outer layers, including the exosporium, coat, and cortex, act as protective barriers against heat. The cortex, in particular, contains high levels of calcium dipicolinate, a compound that stabilizes the spore’s DNA and proteins during heat exposure. Additionally, the spore’s low water content reduces the mobility of molecules, slowing down heat-induced damage. These structural features enable B. cereus spores to withstand temperatures up to 100°C for extended periods, far exceeding the tolerance of their vegetative forms.

Another critical factor in the heat resistance of B. cereus spores is their ability to repair heat-induced damage. Spores possess a small, dormant genome that remains protected within the core. When exposed to heat, DNA damage may occur, but upon germination, the spore activates repair enzymes to restore its genetic integrity. This repair capability is particularly effective at sublethal temperatures, where spores can recover and resume growth. For instance, spores exposed to 70–80°C for 10 minutes may exhibit DNA damage but can often repair it during germination, ensuring survival.

To combat B. cereus spores in food processing, it is essential to apply heat treatments that exceed their resistance thresholds. For example, moist heat treatments at 121°C for 3–5 minutes, commonly used in canning, are effective in destroying most B. cereus spores. However, dry heat treatments are less effective due to the spore’s low water content, which limits heat penetration. Combining heat with other stressors, such as high pressure or chemical agents, can enhance spore inactivation. For instance, adding 2% sodium chloride to a heat treatment can reduce the D-value (time required to reduce spore population by 90%) by up to 50%.

Despite their remarkable heat resistance, B. cereus spores are not invincible. Prolonged exposure to high temperatures, even above their typical resistance range, will eventually lead to spore inactivation. For example, holding temperatures at 130°C for 10–15 minutes can achieve complete spore destruction in most food matrices. However, achieving such temperatures in industrial settings requires careful process design to avoid damaging the food product. Practical tips include preheating equipment to ensure rapid temperature escalation and monitoring core temperatures to confirm uniform heat distribution.

In conclusion, the heat resistance of B. cereus spores is a complex interplay of structural protection and repair mechanisms. While these spores can withstand moderate heat treatments, they succumb to prolonged exposure to high temperatures or combined stressors. By understanding these mechanisms, food processors can design targeted interventions to ensure the safety of their products. Effective control of B. cereus spores requires a combination of scientific knowledge, precise process control, and practical application of heat treatments tailored to specific food matrices.

Understanding Spore-Forming Bacteria: Survival Mechanisms and Health Implications

You may want to see also

Thermal Inactivation Kinetics: Studying the rate of spore destruction at varying heat levels

Bacillus cereus spores are notorious for their resilience, surviving conditions that would destroy most other microorganisms. However, their heat resistance is not absolute. Thermal inactivation kinetics provides a quantitative framework to understand how these spores succumb to heat, offering critical insights for food safety and sterilization processes. By studying the rate of spore destruction at varying heat levels, researchers can pinpoint the temperature and time combinations that ensure complete inactivation, minimizing the risk of foodborne illness.

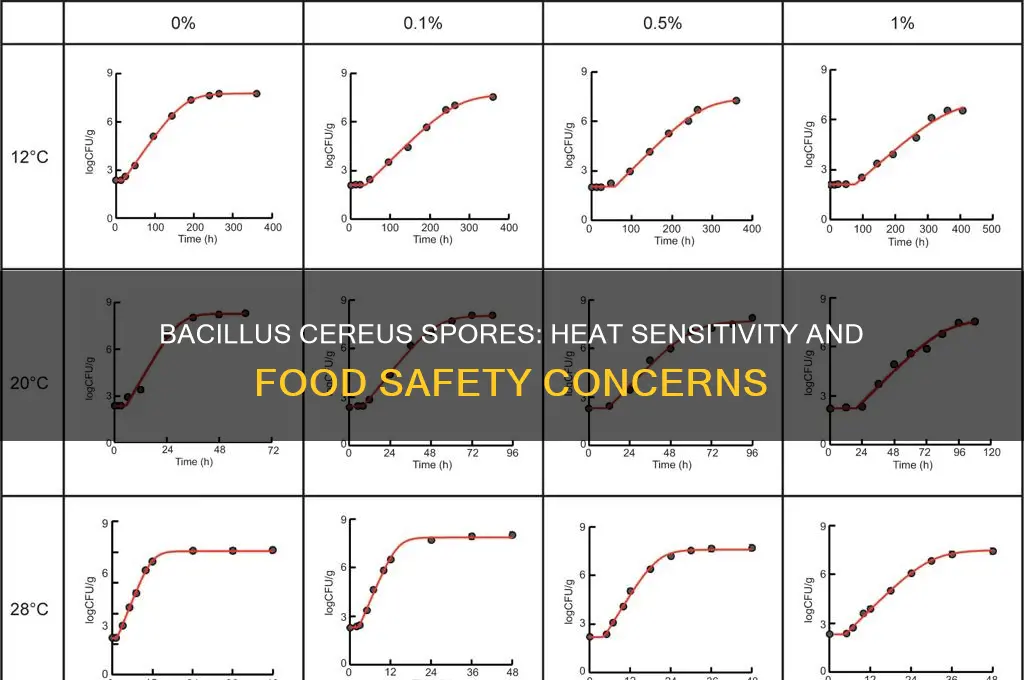

To conduct such studies, scientists employ a systematic approach. Spores are exposed to controlled temperatures ranging from 80°C to 120°C, with exposure times varying from seconds to hours. The decimal reduction time (D-value), defined as the time required to reduce the spore population by 90%, is a key metric. For instance, at 100°C, the D-value for B. cereus spores is approximately 2-5 minutes, depending on strain and environmental factors. Higher temperatures significantly reduce the D-value; at 120°C, spores may be inactivated within seconds. These data are plotted on thermal death time curves, which serve as practical tools for designing heat treatment protocols in industries like food processing and healthcare.

While thermal inactivation is effective, it is not without challenges. Spores in different matrices (e.g., rice, dairy, or soil) may exhibit varying resistance due to protective effects of surrounding materials. For example, spores in starchy foods like rice often require longer heating times due to the insulating properties of the matrix. Additionally, sublethal heat treatments can induce heat shock proteins, potentially increasing spore resistance. Therefore, studies must account for these variables to ensure accurate predictions of spore inactivation.

Practical applications of thermal inactivation kinetics extend beyond the lab. In food processing, retorting processes are calibrated using D-values to achieve commercial sterility. For instance, canned foods are typically heated to 121°C for 3-4 minutes to ensure B. cereus spores are destroyed. Similarly, in healthcare, autoclaves operate at 121°C for 15-20 minutes to sterilize medical instruments. Understanding these kinetics allows industries to optimize processes, balancing safety with energy efficiency and product quality.

In conclusion, thermal inactivation kinetics is a powerful tool for unraveling the heat lability of B. cereus spores. By systematically studying spore destruction rates at varying heat levels, researchers and practitioners can design targeted interventions that safeguard public health. Whether in food production or medical sterilization, this knowledge ensures that heat treatments are both effective and efficient, leaving no room for spore survival.

Are Spore Servers Still Active in 2023? A Comprehensive Update

You may want to see also

Food Processing Impact: Effects of pasteurization, sterilization, and cooking on spore viability

Bacillus cereus spores are notoriously resistant to heat, a trait that poses significant challenges in food processing. While pasteurization, sterilization, and cooking are designed to eliminate pathogens, their effectiveness against B. cereus spores varies widely depending on the method and conditions applied. Understanding these differences is critical for ensuring food safety and preventing spore-related contamination.

Pasteurization, typically performed at temperatures between 63°C and 85°C for 15 to 30 seconds, is effective against vegetative cells of B. cereus but falls short when it comes to spores. For example, milk pasteurization at 72°C for 15 seconds (HTST method) reduces vegetative B. cereus but does not eliminate spores. Similarly, in canned foods, pasteurization at 70°C for 10 minutes may not suffice to destroy spores, which can survive and germinate under favorable conditions. To mitigate this, combining pasteurization with other hurdles like pH control or preservatives is recommended.

Sterilization, involving temperatures above 100°C (121°C for 15–30 minutes in autoclaves), is more effective against B. cereus spores. Commercial sterilization processes, such as those used in canned goods, aim to achieve a 12-log reduction in spore count, ensuring their destruction. However, incomplete sterilization or post-process contamination can still lead to spore survival. For instance, in low-acid canned foods, even a single surviving spore can grow and produce toxins if the product is mishandled after processing. Rigorous monitoring of time, temperature, and sealing integrity is essential to prevent such risks.

Cooking methods, such as boiling, frying, or baking, vary in their impact on spore viability. Boiling at 100°C for 10 minutes reduces spore counts but does not guarantee complete elimination. Frying at temperatures above 150°C can be more effective, as spores are exposed to both heat and desiccation. However, uneven heating in large food items, like rice or meat, can leave spores intact in cooler internal regions. Reheating cooked food to at least 75°C for 2–3 minutes is a practical tip to minimize spore survival, but it is not foolproof. Proper storage and handling remain crucial to prevent spore germination.

In summary, while pasteurization, sterilization, and cooking play vital roles in food safety, their efficacy against B. cereus spores is method-dependent. Pasteurization is inadequate for spore destruction, sterilization is reliable when properly executed, and cooking requires careful attention to temperature and duration. Combining these processes with additional hurdles, such as refrigeration or acidification, enhances safety. For food processors and consumers alike, understanding these limitations is key to preventing B. cereus-related illnesses.

Understanding Spores: Definition, Function, and Significance in Nature

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Strain Variability: Differences in heat sensitivity among B. cereus strains and their spores

Bacillus cereus, a ubiquitous foodborne pathogen, exhibits significant strain variability in heat sensitivity, complicating efforts to standardize thermal inactivation protocols. While some strains and their spores are effectively eliminated at temperatures above 121°C for 3 minutes (a common industrial sterilization benchmark), others persist even after prolonged exposure to similar conditions. This variability is attributed to differences in spore coat composition, germination mechanisms, and genetic factors such as plasmid-encoded heat resistance genes. For instance, strains isolated from dairy environments often demonstrate higher heat tolerance compared to those from soil, likely due to selective pressures in their respective habitats. Understanding these differences is critical for food safety, as underestimating a strain’s heat resistance can lead to survival of spores in processed foods, posing risks of toxin production and illness.

To address strain variability, researchers employ differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and isothermal microcalorimetry to quantify heat resistance among B. cereus isolates. These techniques reveal that some strains require temperatures exceeding 130°C for complete inactivation, while others are inactivated at 110°C. Practical implications for food processing include the need for strain-specific thermal treatments, particularly in industries like canned food production, where spore survival can lead to spoilage or foodborne outbreaks. For example, low-acid canned foods must adhere to FDA guidelines of 121°C for 3 minutes, but this may be insufficient for highly heat-resistant strains. Manufacturers should consider additional hurdles, such as combining heat treatment with antimicrobial agents or adjusting processing times based on strain-specific data.

From a persuasive standpoint, investing in strain-specific heat resistance profiling is not just a scientific endeavor but a public health imperative. Outbreaks linked to B. cereus, such as the 2018 incident involving contaminated milkshakes in the UK, underscore the consequences of overlooking strain variability. Regulatory bodies and food producers must prioritize molecular typing and heat resistance testing of B. cereus isolates to tailor thermal processing protocols. For small-scale producers, adopting rapid detection methods like PCR-based assays can identify high-risk strains early, enabling targeted interventions. Ignoring this variability risks not only consumer health but also brand reputation and economic stability in the food industry.

Comparatively, strain variability in B. cereus contrasts with pathogens like Clostridium botulinum, where heat resistance is more uniform across strains. This difference highlights the need for pathogen-specific approaches in food safety management. While C. botulinum spores are consistently inactivated at 121°C for 3 minutes, B. cereus requires a more nuanced strategy. For instance, in rice-based dishes, where B. cereus is a common contaminant, rapid cooling (below 10°C within 90 minutes) and reheating to 75°C can mitigate spore germination and toxin production, even if spores survive initial cooking. Such comparative insights emphasize the importance of tailoring interventions to the unique characteristics of each pathogen.

In conclusion, strain variability in heat sensitivity among B. cereus strains and their spores demands a shift from one-size-fits-all thermal treatments to evidence-based, strain-specific protocols. By leveraging advanced analytical tools, adopting multi-hurdle approaches, and prioritizing molecular surveillance, the food industry can effectively manage this variability. Practical steps include routine testing of processing environments for B. cereus isolates, adjusting thermal treatments based on resistance profiles, and educating food handlers on critical control points like cooling and reheating. Addressing strain variability not only enhances food safety but also builds resilience against emerging strains in an evolving food landscape.

Can Heat Kill Mold Spores? Effective Temperatures and Methods Explained

You may want to see also

Survival in Heat-Treated Foods: Persistence of spores in processed foods despite thermal treatments

Bacillus cereus spores are notorious for their resilience, often surviving thermal treatments that would eliminate most other pathogens. Despite exposure to temperatures exceeding 100°C, these spores can persist in processed foods, posing a significant food safety challenge. This survival is attributed to their robust structure, which includes a thick protein coat and a resistant outer layer that protects the genetic material within. Understanding this persistence is crucial for developing effective strategies to mitigate contamination in heat-treated foods.

One key factor in spore survival is the duration and intensity of heat treatment. While pasteurization (typically 72°C for 15 seconds) may reduce spore counts, it often fails to eliminate them entirely. For example, in canned vegetables or pasteurized dairy products, spores can remain dormant, only to germinate and multiply under favorable conditions post-processing. High-temperature short-time (HTST) treatments, such as ultra-high temperature (UHT) processing at 135–150°C for 2–5 seconds, are more effective but still not foolproof. Spores in low-moisture foods, like spices or dried grains, are particularly challenging due to their reduced water activity, which further enhances heat resistance.

The persistence of B. cereus spores in processed foods highlights the need for multi-faceted control measures. Combining thermal treatments with additional interventions, such as acidification, antimicrobial agents, or modified atmosphere packaging, can improve efficacy. For instance, lowering the pH of a product below 4.6 can inhibit spore germination, while incorporating preservatives like nisin can target vegetative cells. However, these approaches must be carefully calibrated to avoid compromising product quality or safety.

Practical tips for food manufacturers include rigorous monitoring of processing parameters, such as temperature and time, to ensure consistency. Post-processing contamination must also be prevented through strict hygiene practices and environmental monitoring. For consumers, reheating processed foods to at least 75°C can reduce spore viability, but this is not a guarantee of safety. Ultimately, the persistence of B. cereus spores in heat-treated foods underscores the importance of a proactive, science-based approach to food safety, combining thermal treatments with complementary strategies to minimize risk.

Seeds vs. Spores: Unraveling the Unique Differences in Plant Reproduction

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Bacillus cereus spores are generally heat resistant, not heat labile. They can survive high temperatures, including those used in typical cooking processes.

Bacillus cereus spores typically require temperatures above 121°C (250°F) for at least 15-30 minutes, such as those achieved in autoclaving, to ensure their destruction.

Yes, Bacillus cereus spores can survive boiling water (100°C or 212°F) for extended periods, as this temperature is not sufficient to kill them.