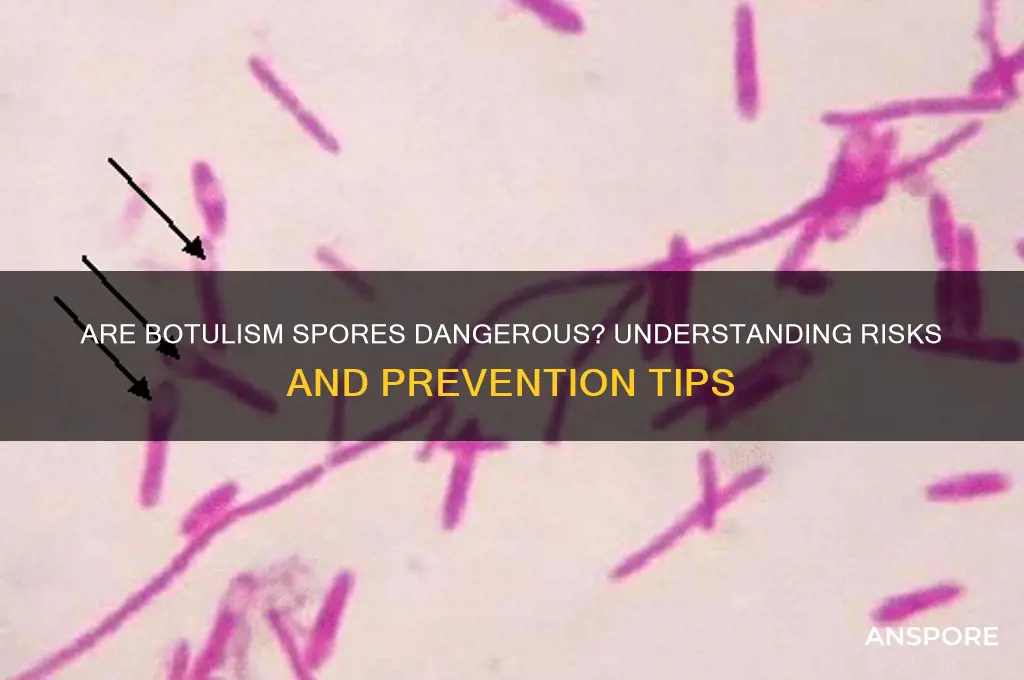

Botulism spores, produced by the bacterium *Clostridium botulinum*, are highly resilient and can survive in various environments, including soil, water, and improperly processed foods. While the spores themselves are not harmful, they become dangerous when they germinate and produce botulinum toxin, one of the most potent toxins known to science. This toxin can cause botulism, a severe and potentially fatal illness characterized by muscle paralysis, respiratory failure, and other life-threatening symptoms. Understanding the risks associated with botulism spores is crucial, as they can contaminate food sources like home-canned goods, honey, and certain types of fish, posing a significant public health concern if not handled or processed correctly.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Heat Resistance | Highly resistant to heat, surviving boiling temperatures for several hours. |

| Environmental Persistence | Can survive in soil, sediments, and aquatic environments for years. |

| Toxicity | Spores themselves are not toxic; only the toxin produced by germinated spores is dangerous. |

| Germination Conditions | Require anaerobic (oxygen-free) conditions, low acidity, and specific nutrients to germinate. |

| Toxin Production | Once germinated, bacteria produce botulinum toxin, one of the most potent toxins known. |

| Human Risk | Spores are harmless if ingested but pose a risk if they germinate and produce toxin in the gut or wounds. |

| Food Contamination | Commonly found in improperly canned foods, where conditions allow spore germination and toxin production. |

| Prevention | Proper food handling, canning techniques, and avoiding consumption of suspect foods reduce risk. |

| Treatment | Antitoxin administration and supportive care are critical if toxin exposure occurs. |

| Vaccination | No widely available vaccine for humans, but antitoxins are used for treatment and prevention in high-risk cases. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spores in Food: Botulism spores survive in improperly canned or preserved foods, posing serious health risks

- Environmental Presence: Spores exist in soil, dust, and sediments, but are harmless unless ingested or inhaled

- Heat Resistance: Spores withstand boiling temperatures, requiring specific conditions to be destroyed effectively

- Germination Risk: Spores become dangerous only when they germinate and produce toxins in favorable environments

- Human Exposure: Inhalation or open wound exposure to spores can lead to rare but severe infections

Spores in Food: Botulism spores survive in improperly canned or preserved foods, posing serious health risks

Botulism spores, produced by the bacterium *Clostridium botulinum*, are remarkably resilient, capable of surviving in environments devoid of oxygen and enduring temperatures up to 100°C for several hours. This durability makes them particularly dangerous in improperly canned or preserved foods, where they can germinate, produce toxins, and cause severe illness. Unlike the spores themselves, the botulinum toxin is one of the most potent known to science, with a lethal dose for humans estimated at just 0.000001 gram. This underscores the critical importance of proper food handling and preservation techniques to prevent spore activation.

To mitigate the risk, home canners and preservers must adhere to specific guidelines. Pressure canning at temperatures above 121°C is essential for low-acid foods like vegetables, meats, and soups, as these conditions effectively destroy spores. Boiling water bath canning, while sufficient for high-acid foods like fruits and pickles, is inadequate for low-acid items. Additionally, ensuring proper sealing of jars and checking for signs of spoilage, such as bulging lids or foul odors, are crucial steps. For those using commercially canned products, inspecting cans for dents, leaks, or swelling before consumption can prevent exposure to contaminated food.

Comparatively, the risk of botulism from commercially produced foods is significantly lower due to stringent regulatory standards and industrial sterilization processes. However, home-preserved foods account for a disproportionate number of botulism cases, particularly in regions where traditional preservation methods are common. For instance, cases have been linked to improperly fermented foods like homemade pickles or cured meats. This highlights the need for education and resources to empower individuals to preserve food safely, especially in communities where such practices are prevalent.

The health risks associated with botulism are severe and swift. Symptoms typically appear within 12 to 36 hours of consuming contaminated food and include blurred vision, difficulty swallowing, and muscle weakness, progressing to paralysis in severe cases. Infants are particularly vulnerable, as their digestive systems are less developed, making them susceptible to botulism from sources like honey, which may contain spores. Prompt medical attention, including administration of antitoxins and supportive care, is critical for survival. Awareness of these symptoms and their rapid onset can be lifesaving, emphasizing the need for vigilance in food preparation and consumption.

In conclusion, while botulism spores are inherently dangerous, their threat can be neutralized through informed practices. By understanding the conditions under which spores thrive and implementing proper preservation techniques, individuals can enjoy safely canned and preserved foods without fear. Education, adherence to guidelines, and awareness of symptoms collectively form a robust defense against this preventable yet potentially fatal illness.

Are Anthrax Spores Identical? Unraveling the Genetic Similarities and Differences

You may want to see also

Environmental Presence: Spores exist in soil, dust, and sediments, but are harmless unless ingested or inhaled

Botulism spores, produced by the bacterium *Clostridium botulinum*, are ubiquitous in the environment, lurking in soil, dust, and sediments. This widespread presence might sound alarming, but it’s important to understand that these spores are inherently dormant and harmless in their natural state. They lack the ability to cause harm unless activated under specific conditions. For instance, in environments devoid of oxygen, such as sealed containers or deep wounds, the spores can germinate into active bacteria, which then produce the potent botulinum toxin. This toxin, not the spores themselves, is the true danger, capable of causing paralysis and even death in severe cases.

Consider the practical implications of this environmental presence. Gardening, for example, exposes individuals to soil teeming with botulism spores, yet this activity is generally safe. The risk arises only if contaminated soil is ingested or if spores enter the body through open wounds. Similarly, household dust may contain spores, but routine cleaning and good hygiene practices effectively mitigate any potential threat. Even in natural water bodies, where spores settle in sediments, the risk of exposure is minimal unless the water is consumed untreated or used in food preparation without proper sterilization.

To contextualize the risk, it’s helpful to compare botulism spores to other environmental hazards. While lead in soil or asbestos in dust pose immediate dangers upon exposure, botulism spores require specific conditions to become harmful. For instance, the ingestion of as few as 30–130 botulinum toxin spores can lead to botulism in infants, whose digestive systems are less developed, but adults typically require much higher doses or direct toxin exposure to be affected. This highlights the importance of age-specific precautions, such as avoiding honey for children under one year old, as it can contain botulism spores.

For those concerned about environmental exposure, practical steps can further reduce risk. When handling soil or dust, wearing gloves and washing hands thoroughly afterward can prevent accidental ingestion. Food preservation methods, such as boiling home-canned goods for at least 10 minutes before consumption, destroy any activated bacteria or toxins. Additionally, ensuring proper ventilation in indoor spaces minimizes the inhalation of dust particles that might carry spores. By understanding the conditions under which spores become dangerous, individuals can navigate their environment with confidence rather than fear.

Ultimately, the environmental presence of botulism spores is a reminder of the delicate balance between microbial life and human safety. While these spores are everywhere, their potential to cause harm is limited by their dormant nature and the specific conditions required for activation. By focusing on prevention—through hygiene, proper food handling, and awareness of high-risk scenarios—individuals can coexist with these spores without undue concern. The key takeaway is not to avoid the environment but to respect its complexities and take informed, targeted precautions.

Understanding Milky Spore: A Natural Grub Control Solution for Lawns

You may want to see also

Heat Resistance: Spores withstand boiling temperatures, requiring specific conditions to be destroyed effectively

Botulism spores, produced by the bacterium *Clostridium botulinum*, are remarkably resilient, capable of surviving boiling temperatures that would destroy most other pathogens. This heat resistance is a critical factor in their danger, as it allows them to persist in environments where food is improperly processed or stored. For instance, boiling water (100°C or 212°F) is insufficient to eliminate these spores, which can remain viable even after prolonged exposure to such temperatures. This resilience underscores the necessity of specific, more extreme conditions to ensure their destruction, such as pressure canning at temperatures above 121°C (250°F) for a minimum of 30 minutes, depending on the food type and container size.

To effectively destroy botulism spores, understanding their heat resistance is paramount. Home canners, for example, must use pressure canners rather than boiling water baths for low-acid foods like vegetables, meats, and soups. A boiling water bath, typically used for high-acid foods like fruits and pickles, reaches only 100°C, which is inadequate for spore destruction. Pressure canners, on the other hand, achieve temperatures of 121°C or higher, providing the necessary conditions to kill spores. Failure to follow these guidelines can result in spore survival, leading to botulism toxin production in sealed jars, which is odorless, tasteless, and potentially fatal if consumed.

The danger of botulism spores extends beyond home canning to commercial food production and even natural environments. For instance, honey, a common household item, can contain botulism spores, posing a risk to infants under one year old whose digestive systems are not yet capable of neutralizing them. This is why health authorities universally advise against feeding honey to babies. Similarly, improperly processed canned foods, whether homemade or commercially produced, can harbor spores if not heated to the required temperatures. This highlights the importance of adhering to strict processing guidelines, such as those provided by the USDA, to ensure food safety.

A comparative analysis of spore resistance reveals why standard cooking methods are ineffective. While most bacteria are killed at temperatures between 60°C and 80°C (140°F to 176°F), botulism spores require temperatures exceeding 121°C to be destroyed. This is why foods like baked potatoes cooked in aluminum foil, which may not reach these temperatures internally, can pose a risk if left at room temperature. The spores can survive the cooking process and, in the absence of oxygen within the foil, germinate and produce toxin. Practical tips include using a food thermometer to ensure internal temperatures exceed 121°C during cooking and promptly refrigerating leftovers to inhibit spore germination.

In conclusion, the heat resistance of botulism spores demands specific, scientifically validated methods to ensure their destruction. Whether in home canning, commercial food production, or everyday cooking, understanding and applying these methods is critical to preventing botulism. By following guidelines such as pressure canning for low-acid foods, avoiding honey for infants, and ensuring proper cooking and storage temperatures, individuals can mitigate the risks associated with these resilient spores. This knowledge is not just theoretical but a practical necessity for safeguarding health in various food-related contexts.

Understanding Spore Prints: A Beginner's Guide to Mushroom Identification

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Germination Risk: Spores become dangerous only when they germinate and produce toxins in favorable environments

Botulism spores, produced by the bacterium *Clostridium botulinum*, are remarkably resilient, capable of surviving extreme conditions such as high temperatures, desiccation, and harsh chemicals. This durability allows them to persist in soil, water, and even canned foods. However, their mere presence does not pose an immediate threat. The danger arises only when these spores germinate, transforming into active bacteria that produce potent neurotoxins. Understanding this germination process is crucial, as it highlights the specific conditions required for spores to become hazardous.

Germination of botulism spores is not a spontaneous event; it demands a favorable environment characterized by low oxygen levels, warmth, and a pH range between 4.6 and 9.0. These conditions are often found in improperly processed or stored foods, particularly low-acid canned goods like vegetables, meats, and fish. For instance, a home-canned jar of green beans stored at room temperature provides an ideal setting for spore germination. The absence of oxygen inside the sealed jar, combined with the warmth of the environment, triggers the spores to activate and begin toxin production. This toxin, even in minute quantities (as little as 0.0007 micrograms per kilogram of body weight), can cause severe paralysis and, in some cases, death.

Preventing germination is far more effective than dealing with active toxin-producing bacteria. Practical steps include proper food handling and storage. For home canning, always use a pressure canner for low-acid foods to achieve temperatures above 240°F (116°C), which destroys spores. Store canned goods in a cool, dry place, ideally below 75°F (24°C), to inhibit spore activation. Commercially processed foods undergo strict sterilization protocols, but consumers should still inspect cans for bulging or leaks, which indicate potential contamination. For infants, avoid feeding them honey or corn syrup, as these can contain botulism spores that may germinate in their immature digestive systems.

Comparing botulism spores to other bacterial threats underscores their unique risk profile. Unlike pathogens like *Salmonella* or *E. coli*, which are dangerous in their active form, botulism spores are harmless until they germinate. This distinction emphasizes the importance of targeting environmental conditions rather than the spores themselves. While boiling water (212°F/100°C) can kill active *C. botulinum* bacteria, it does not eliminate spores, which require much higher temperatures or prolonged exposure to heat. This makes prevention through proper food processing and storage the most effective strategy.

In summary, botulism spores transition from benign to deadly only when they germinate in favorable conditions. By controlling factors like temperature, oxygen levels, and pH, individuals can mitigate the risk of toxin production. Whether through meticulous home canning practices or vigilant food inspection, understanding the germination process empowers people to protect themselves from this silent threat. The key takeaway is clear: it’s not the spores themselves, but the environments we create that determine their danger.

Effective Temperatures to Eliminate Mold Spores: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Human Exposure: Inhalation or open wound exposure to spores can lead to rare but severe infections

Botulism spores, though dormant and generally harmless in their natural state, pose a significant threat when introduced into the human body through inhalation or open wound exposure. These spores, produced by the bacterium *Clostridium botulinum*, are remarkably resilient, capable of surviving in soil, dust, and even extreme environmental conditions. While ingestion is the most common route of infection, inhalation or wound contamination can lead to rare but severe infections, particularly in specific high-risk scenarios. For instance, laboratory workers handling botulinum toxin or individuals exposed to contaminated environments, such as construction sites with disturbed soil, face heightened risks. Understanding these exposure pathways is critical for prevention and early intervention.

Inhalation of botulism spores is an uncommon but potentially life-threatening scenario, often associated with bioterrorism or industrial accidents. The spores, when inhaled, can germinate in the lungs, leading to a condition known as inhalational botulism. This form of infection is exceptionally rare, with fewer than 100 documented cases worldwide. However, its severity cannot be overstated—symptoms include respiratory paralysis, muscle weakness, and difficulty breathing, often requiring immediate mechanical ventilation. The lethal dose of botulinum toxin via inhalation is estimated to be as low as 0.001 micrograms per kilogram of body weight, making it one of the most potent toxins known. Early recognition of symptoms, such as blurred vision or slurred speech, is crucial for prompt medical intervention.

Open wound exposure to botulism spores, while less common than ingestion, can result in wound botulism, a condition primarily associated with intravenous drug use or traumatic injuries in contaminated environments. The spores enter the body through breaks in the skin, where they germinate and produce toxin in the absence of oxygen. This form of botulism is particularly insidious because symptoms may not appear for several days, delaying diagnosis. High-risk groups include individuals who inject drugs, especially those using black tar heroin, which has been linked to soil contamination. Prevention strategies include thorough wound cleaning with antiseptic solutions and avoiding exposure to potentially contaminated materials. For healthcare providers, recognizing the link between injection drug use and wound botulism is essential for timely treatment.

Practical precautions can significantly reduce the risk of botulism from inhalation or wound exposure. For individuals working in high-risk environments, such as laboratories or construction sites, wearing personal protective equipment (PPE), including masks and gloves, is non-negotiable. Proper ventilation in enclosed spaces and regular decontamination of equipment can further minimize spore exposure. In the event of a suspected exposure, immediate medical consultation is critical. Treatment typically involves administration of antitoxins, such as botulism immune globulin, and supportive care to manage symptoms. Public health education, particularly in communities with high rates of injection drug use, can play a vital role in preventing wound botulism. By combining awareness with proactive measures, the rare but severe risks of botulism spore exposure can be effectively mitigated.

Mastering Liquid Culture: A Step-by-Step Guide from Spore Syringe

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Botulism spores themselves are not harmful, but they can become dangerous if they germinate and produce the botulinum toxin in conditions like low oxygen and warm temperatures.

Yes, botulism spores are highly resistant and can survive in food, especially in low-acid, improperly canned, or preserved items. They pose a risk if they grow and produce toxin.

Botulism spores are commonly found in soil and water but are not harmful in these environments unless they enter a host or food source where they can germinate and produce toxin.

Botulism spores are heat-resistant and cannot be killed by normal cooking temperatures. However, the toxin they produce can be destroyed by boiling food for at least 10 minutes.