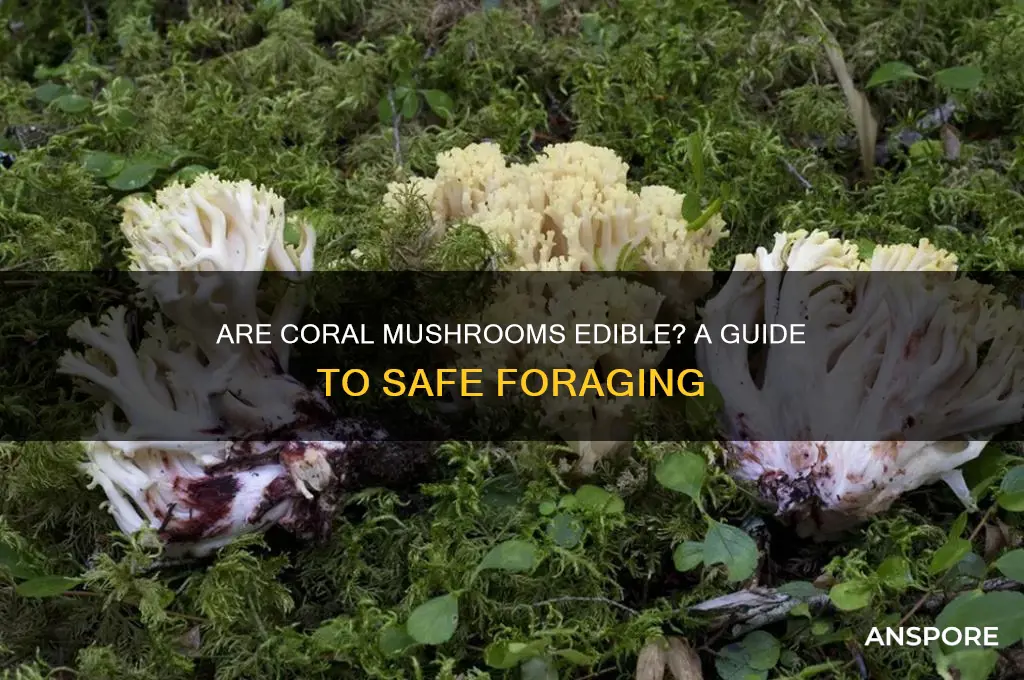

Coral mushrooms, known for their distinctive branching, finger-like structures, are a fascinating group of fungi that often capture the attention of foragers and nature enthusiasts. While some species, such as the yellow coral mushroom (*Clavulina chrysopaea*), are considered edible and even prized in certain cuisines, many others are either inedible or lack culinary value. It is crucial to approach coral mushrooms with caution, as accurate identification is essential; misidentification can lead to consuming toxic species. Consulting a reliable field guide or expert is highly recommended before considering any coral mushroom for consumption.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Edibility | Most coral mushrooms are edible, but some species can be toxic or cause gastrointestinal upset. |

| Common Edible Species | Ramaria formosa (Beautiful Clavaria), Ramaria botrytis (Coral Tooth), Ramaria aurea (Golden Coral) |

| Toxic Species | Ramaria pallida (Pallid Coral), Ramaria stricta (Upright Coral) |

| Taste | Mild to slightly nutty or fruity |

| Texture | Brittle, fragile, and often branching |

| Color | Vibrant hues of yellow, orange, red, purple, or white |

| Habitat | Found in forests, often near coniferous or deciduous trees |

| Season | Typically fruiting in late summer to fall |

| Identification Difficulty | Moderate to high; requires careful examination of features like color, branching pattern, and spore print |

| Precautions | Always cook before consuming, as some species may cause digestive issues when raw. Avoid consuming large quantities of any wild mushroom without proper identification. |

| Conservation Status | Not typically threatened, but habitat destruction can impact populations |

| Look-alikes | Some toxic species resemble edible corals, emphasizing the need for accurate identification |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Identifying Coral Mushrooms: Key features to distinguish edible from poisonous varieties safely

- Edible Species: Popular coral mushrooms like *Ramaria botrytis* and their culinary uses

- Toxic Look-Alikes: Dangerous species resembling edible coral mushrooms and how to avoid them

- Preparation Tips: Best methods for cleaning, cooking, and preserving edible coral mushrooms

- Foraging Safety: Guidelines for responsibly harvesting coral mushrooms in the wild

Identifying Coral Mushrooms: Key features to distinguish edible from poisonous varieties safely

Coral mushrooms, with their distinctive branching structures, often captivate foragers, but not all are safe to eat. Identifying edible varieties requires keen observation and knowledge of key features. Start by examining the color: edible species like *Ramaria formosa* (the pinkish-white coral mushroom) typically lack bright, garish hues, while poisonous ones may display vivid yellows, greens, or reds. However, color alone is insufficient; always cross-reference with other characteristics.

Texture and consistency are equally critical. Edible coral mushrooms usually have a firm, brittle texture that snaps cleanly when broken, whereas poisonous varieties may feel softer or rubbery. For instance, *Ramaria stricta*, a toxic species, often has a more pliable structure. Additionally, inspect the branching pattern: edible corals tend to have neatly forked, symmetrical branches, while poisonous ones may appear irregular or jagged. Always carry a field guide or use a reliable app to compare your findings.

One often-overlooked feature is the spore print. While time-consuming, this method can provide definitive clues. Edible coral mushrooms typically produce cream, yellow, or pale orange spores, whereas poisonous species may yield darker or more unusual colors. To take a spore print, place a cap gill-side down on white paper overnight. This step, though optional, adds an extra layer of safety for novice foragers.

Finally, consider habitat and seasonality. Edible coral mushrooms often grow in coniferous or mixed woodlands during late summer to fall, while poisonous varieties may appear in less typical environments or at odd times of the year. For example, *Ramaria formosa* thrives under pines, whereas toxic species like *Clavulina cristata* prefer deciduous forests. Always avoid consuming any mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity, and consult an expert if in doubt. Safe foraging relies on patience, practice, and a commitment to detail.

Edible Species: Popular coral mushrooms like *Ramaria botrytis* and their culinary uses

Among the diverse array of coral mushrooms, *Ramaria botrytis*, commonly known as the cauliflower coral or clammy coral, stands out as a prized edible species. Its distinctive cluster of branching, yellowish-orange fruiting bodies resembles a cauliflower, making it easily identifiable for foragers. Unlike some of its toxic relatives, *R. botrytis* is not only safe to eat but also boasts a mild, nutty flavor that pairs well with various culinary creations. However, proper identification is crucial, as misidentification can lead to severe consequences. Always consult a field guide or an expert before harvesting.

In the kitchen, *Ramaria botrytis* shines as a versatile ingredient. Its firm texture holds up well to cooking methods like sautéing, grilling, or roasting, making it an excellent addition to stir-fries, risottos, or even as a standalone side dish. For a simple yet flavorful preparation, sauté the cleaned mushrooms in butter with garlic and thyme, then finish with a splash of lemon juice to brighten the earthy tones. Alternatively, dry the mushrooms for long-term storage and rehydrate them later in soups or stews, where they’ll absorb flavors while adding a subtle umami depth. Avoid overcooking, as this can cause the mushrooms to become mushy and lose their delicate texture.

While *R. botrytis* is generally safe for consumption, it’s essential to exercise caution. Some individuals may experience mild gastrointestinal discomfort, particularly if consumed in large quantities. As a rule of thumb, start with a small portion (around 50–100 grams per person) to gauge tolerance. Additionally, always cook these mushrooms thoroughly, as raw coral mushrooms can be difficult to digest and may contain trace compounds that are neutralized by heat. Pregnant or nursing individuals, as well as those with mushroom allergies, should avoid consuming them altogether.

Compared to other edible mushrooms, *Ramaria botrytis* offers a unique combination of accessibility and culinary potential. Its widespread distribution in North America and Europe makes it a favorite among foragers, while its flavor profile sets it apart from more common varieties like button or shiitake mushrooms. For those new to foraging, *R. botrytis* serves as an excellent entry point, provided proper identification techniques are followed. Pairing it with richer ingredients like cream or cheese can elevate its natural nuttiness, while lighter preparations allow its subtle nuances to take center stage. Whether you’re an experienced chef or a curious home cook, this coral mushroom is a worthy addition to your culinary repertoire.

Toxic Look-Alikes: Dangerous species resembling edible coral mushrooms and how to avoid them

Coral mushrooms, with their delicate, branching structures, often tempt foragers with their apparent edibility. However, the forest floor is a minefield of toxic look-alikes that mimic their appearance. One such imposter is the Ramaria formosa, commonly known as the Pinkish Coral Mushroom. While it shares the coral mushroom’s branching habit, it contains a toxin that causes severe gastrointestinal distress, including vomiting and diarrhea, within hours of ingestion. Unlike its edible counterparts, *R. formosa* often has a slightly off-putting odor and a more garish pink or orange coloration, but these features can be subtle, making identification treacherous for the untrained eye.

To avoid such dangers, foragers must adopt a meticulous approach. First, examine the mushroom’s spore color—edible coral mushrooms typically produce white or pale yellow spores, while *R. formosa* and other toxic species often have ochre or brownish spores. Second, habitat matters: edible corals like *Ramaria botrytis* (the cauliflower coral) are commonly found in coniferous forests, whereas toxic species may prefer deciduous areas. Third, taste tests are risky; instead, carry a reliable field guide or use a mushroom identification app to cross-reference features like branching pattern, color, and odor.

Another deceptive doppelgänger is the Clavulina species, often called club corals. While some are edible, others, like *Clavulina rugosa*, are toxic and cause mild to moderate poisoning. These mushrooms lack the branching structure of true corals, instead forming club-like or spindle-shaped fruiting bodies. A key differentiator is their texture—edible corals are typically brittle, while toxic club corals are often rubbery or gelatinous. Foraging without proper knowledge of these nuances can turn a woodland adventure into a hospital visit.

Children and pets are particularly vulnerable to accidental poisoning, as they may be drawn to the coral-like appearance of these fungi. If ingestion of a suspected toxic species occurs, immediate medical attention is critical. Symptoms can appear within 30 minutes to 2 hours, depending on the toxin. Keep a sample of the mushroom for identification, as this aids in treatment. Prevention is paramount: teach children and pet owners to avoid touching or tasting wild mushrooms, and always forage with an experienced guide or after thorough self-education.

In conclusion, while edible coral mushrooms are a forager’s delight, their toxic look-alikes demand respect and caution. By focusing on spore color, habitat, texture, and odor, and by avoiding risky shortcuts like taste tests, foragers can safely enjoy their harvest. Remember, the forest’s beauty lies in its diversity—but not all that resembles coral is safe to consume.

Explore related products

Preparation Tips: Best methods for cleaning, cooking, and preserving edible coral mushrooms

Coral mushrooms, particularly the edible varieties like *Ramaria botrytis* (the cauliflower mushroom) and *Ramaria formosa* (though the latter is debated and often avoided due to potential toxicity), require careful preparation to ensure safety and enhance flavor. Before diving into cleaning, cooking, or preserving, always confirm the species with a reliable guide or expert, as misidentification can lead to severe consequences. Once verified, the preparation process begins with cleaning, a step that demands precision to preserve the mushroom’s delicate structure while removing debris.

Cleaning coral mushrooms involves a gentle touch to avoid breaking their fragile, branching structure. Start by trimming the base, which is often woody and tough, using a sharp knife or kitchen shears. Next, use a soft brush or damp cloth to remove dirt and debris, avoiding excessive water that can cause the mushrooms to become waterlogged. For particularly stubborn particles, a quick rinse under cold water is acceptable, but pat the mushrooms dry immediately with paper towels or a clean cloth. This method ensures the mushrooms retain their texture and flavor without absorbing excess moisture, which can dilute their earthy taste.

Cooking coral mushrooms highlights their unique texture and flavor, which can be described as nutty, earthy, and slightly sweet. Sautéing is one of the best methods, as it enhances their natural richness. Heat a tablespoon of butter or olive oil in a pan over medium heat, add the mushrooms, and cook for 5–7 minutes, stirring occasionally, until they are golden brown and tender. For a deeper flavor, add minced garlic and fresh herbs like thyme or parsley during the last two minutes of cooking. Alternatively, roasting coral mushrooms at 375°F (190°C) for 15–20 minutes brings out their natural sweetness and creates a crispy exterior. Toss them in olive oil, salt, and pepper before roasting for optimal results.

Preserving coral mushrooms allows you to enjoy their unique qualities year-round. Drying is the most effective method, as it concentrates their flavor and extends their shelf life. To dry, spread the cleaned mushrooms in a single layer on a dehydrator tray or baking sheet, and dry at a low temperature (135°F or 57°C) for 6–12 hours, or until completely dry and brittle. Store the dried mushrooms in an airtight container in a cool, dark place for up to a year. Rehydrate them by soaking in hot water for 15–20 minutes before using in soups, stews, or sauces. Freezing is another option, though it can alter their texture slightly. Blanch the mushrooms in boiling water for 1–2 minutes, plunge them into ice water, drain, and freeze in airtight bags for up to six months.

While coral mushrooms offer a delightful culinary experience, caution is paramount. Always cook them thoroughly, as consuming them raw or undercooked can cause digestive discomfort. Additionally, avoid overharvesting in the wild to ensure the sustainability of these fungi. By following these preparation tips—cleaning with care, cooking to enhance flavor, and preserving for future use—you can safely enjoy the unique qualities of edible coral mushrooms in a variety of dishes.

Foraging Safety: Guidelines for responsibly harvesting coral mushrooms in the wild

Coral mushrooms, with their striking branching structures and vibrant colors, are a forager’s delight—but their beauty demands caution. While many species, like *Ramaria botrytis* (the cauliflower coral mushroom), are edible and prized for their nutty flavor, others can cause gastrointestinal distress or worse. Misidentification is a real risk, as toxic look-alikes like *Ramaria formosa* (the poisonous peach coral) share similar habitats. Before harvesting, ensure you’ve positively identified the species using a reliable field guide or expert consultation. Remember: when in doubt, leave it out.

Responsible foraging begins with respect for the ecosystem. Coral mushrooms play a vital role in forest health, decomposing wood and cycling nutrients. Harvest sustainably by leaving at least two-thirds of any cluster undisturbed, allowing the mycelium to continue its ecological work. Use a sharp knife to cut the base of the mushroom rather than pulling it from the substrate, which can damage the underground network. Avoid foraging in protected areas or where pollution is likely, such as roadside ditches or industrial zones, as mushrooms readily absorb toxins.

Timing is critical for both safety and flavor. Harvest coral mushrooms when they’re young and firm, as older specimens can become woody and less palatable. Early fall is prime foraging season in temperate regions, but always check local conditions. Clean your harvest carefully by brushing off debris or rinsing quickly—coral mushrooms are delicate and can absorb water, spoiling their texture. Store them in a paper bag in the refrigerator, where they’ll keep for 2–3 days, or dry them for longer preservation.

Finally, educate yourself on the legal and ethical dimensions of foraging. Many regions have regulations governing wild mushroom collection, including permit requirements or quantity limits. Always seek permission when foraging on private land and avoid overharvesting in popular areas. Share your knowledge with fellow foragers, emphasizing the importance of leaving no trace and respecting nature’s balance. By adopting these practices, you can enjoy the bounty of coral mushrooms while safeguarding their future—and yours.

Frequently asked questions

No, not all coral mushrooms are edible. While some species like *Ramaria botrytis* (the cauliflower coral mushroom) are safe to eat, others can be toxic or cause digestive issues. Always identify the specific species before consuming.

Accurate identification is key. Edible coral mushrooms typically have a cauliflower-like appearance, mild taste, and lack any bitter or spicy flavors when tested. Consult a field guide or expert for confirmation.

Some coral mushrooms are poisonous, such as *Ramaria formosa* (the pinkish coral mushroom), which can cause gastrointestinal distress. Avoid consuming any coral mushroom unless you are certain of its edibility.

It is not recommended to eat coral mushrooms raw, as they can be difficult to digest and may cause stomach upset. Cooking them thoroughly is advised to improve palatability and safety.

Edible coral mushrooms, like *Ramaria botrytis*, have a mild, earthy flavor similar to other wild mushrooms. They are often used in soups, stews, or sautéed dishes to enhance flavor.