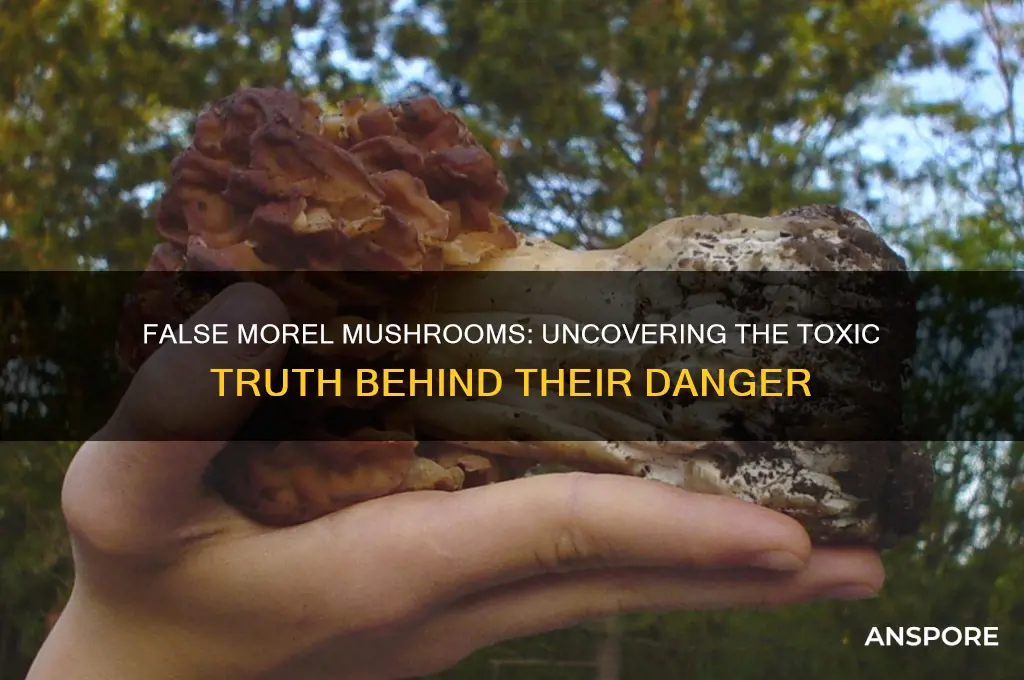

False morel mushrooms, often mistaken for their edible counterparts due to their similar appearance, are indeed highly poisonous and pose a significant risk to those who consume them. These fungi, scientifically known as *Gyromitra esculenta*, contain a toxic compound called gyromitrin, which can cause severe gastrointestinal symptoms, neurological issues, and even organ failure if ingested. Despite their enticing look and historical use in some cultures after extensive preparation, experts strongly advise against consuming false morels, as improper handling can leave dangerous toxins intact. Understanding the risks associated with these mushrooms is crucial for foragers and enthusiasts to avoid accidental poisoning and ensure safety in the wild.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Toxicity | Highly toxic; contains gyromitrin, which converts to monomethylhydrazine (MMH), a toxic compound. |

| Symptoms | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness, abdominal pain, and in severe cases, seizures, liver damage, or death. |

| Appearance | Brain-like, wrinkled, or convoluted caps; often reddish-brown to dark brown in color. |

| Edibility | Considered poisonous and unsafe for consumption, even after cooking or drying. |

| Common Names | False Morel, Brain Mushroom, Beefsteak Morel, Red Morel. |

| Scientific Name | Gyromitra esculenta and other Gyromitra species. |

| Habitat | Found in deciduous and coniferous forests, often near birch, pine, or oak trees. |

| Season | Spring, typically appearing before true morels. |

| Treatment | Immediate medical attention required if ingested; activated charcoal and supportive care may be administered. |

| Prevention | Avoid consumption and accurately identify mushrooms before foraging. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Symptoms of False Morel Poisoning

False morel mushrooms, scientifically known as *Gyromitra esculenta*, contain a toxin called gyromitrin, which breaks down into monomethylhydrazine (MMH) in the body. Ingesting even small amounts of this toxin can lead to severe symptoms, making it crucial to recognize the signs of poisoning early. Symptoms typically appear within 6 to 12 hours after consumption, though they can manifest as early as 2 hours or as late as 24 hours, depending on the amount ingested and individual sensitivity.

The initial symptoms of false morel poisoning often mimic food poisoning, starting with gastrointestinal distress. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain are common and can be severe. These symptoms are the body’s immediate response to the toxin and may lead to dehydration if not managed promptly. It’s essential to rehydrate with oral electrolyte solutions, but medical attention should be sought if symptoms persist or worsen. For children or the elderly, who are more susceptible to dehydration, immediate medical intervention is critical.

As the toxin progresses through the body, neurological symptoms may emerge, signaling a more serious stage of poisoning. Headaches, dizziness, and confusion are early indicators, often followed by muscle cramps, tremors, or seizures. In severe cases, victims may experience ataxia (loss of coordination) or even fall into a coma. These symptoms arise from MMH’s interference with the nervous system, particularly its ability to disrupt neurotransmitter function. Anyone exhibiting neurological symptoms after consuming false morels requires urgent medical care, as these signs can progress rapidly.

Long-term exposure to gyromitrin, such as through repeated consumption of false morels, can lead to chronic symptoms, including liver and kidney damage. While less common than acute poisoning, chronic effects are equally dangerous and often irreversible. Cooking or drying false morels does not eliminate the toxin entirely, so even experienced foragers should avoid them. The safest approach is to treat false morels as inedible and opt for safer mushroom varieties like true morels (*Morchella* species).

In summary, recognizing the symptoms of false morel poisoning—from gastrointestinal distress to severe neurological effects—is vital for timely intervention. If poisoning is suspected, contact a poison control center or seek emergency medical care immediately. Bring a sample of the mushroom for identification if possible. Prevention remains the best strategy: avoid consuming false morels altogether, as their toxin poses a significant health risk, even in small doses.

Mushrooms in Alabama: What to Know and Where to Find Them

You may want to see also

Toxic Compounds in False Morels

False morels, often mistaken for their edible counterparts, harbor a potent toxin known as gyromitrin. This compound, when ingested, converts into monomethylhydrazine, a substance with severe toxic effects on the human body. Even small amounts can lead to symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and in severe cases, seizures or liver failure. Understanding the chemical composition of these mushrooms is crucial for anyone foraging in the wild, as misidentification can have dire consequences.

The toxicity of false morels is not uniform across all species or even within the same mushroom. Factors like age, preparation methods, and individual sensitivity play a role in determining the severity of poisoning. For instance, drying or cooking false morels can reduce gyromitrin levels but does not eliminate the risk entirely. A single false morel contains enough toxin to cause illness, and consuming as little as half a cap can lead to symptoms in sensitive individuals. This variability underscores the importance of avoiding these mushrooms altogether rather than attempting to mitigate their toxicity.

Foraging enthusiasts often debate whether false morels can be safely consumed after proper preparation. However, scientific evidence and historical cases of poisoning strongly advise against this practice. Unlike true morels, which are prized for their flavor and safety, false morels offer no culinary benefit that outweighs their risks. Even experienced foragers have fallen victim to their deceptive appearance, highlighting the need for caution and education in mushroom identification.

If accidental ingestion occurs, immediate medical attention is essential. Symptoms typically appear within 6 to 12 hours, though they can manifest as early as 2 hours or as late as 24 hours after consumption. Treatment may include gastric lavage, activated charcoal, and supportive care to manage symptoms and prevent complications. Awareness of these toxic compounds and their effects can save lives, emphasizing the importance of accurate identification and avoidance of false morels in the wild.

Microwaving Mushrooms Before Stuffing: A Time-Saver or Texture Killer?

You may want to see also

Safe Preparation Methods (If Any)

False morels, despite their enticing appearance, are notorious for containing toxins like gyromitrin, which can cause severe gastrointestinal distress, neurological symptoms, and even organ damage. While some foragers claim these mushrooms can be rendered safe through preparation, the consensus among experts is unequivocal: no method guarantees complete detoxification. However, for those insistent on attempting consumption, certain traditional practices aim to reduce toxin levels, though they come with significant risks.

One widely discussed method involves parboiling—simmering the mushrooms in water for 10–15 minutes, discarding the liquid, and repeating the process. This technique leverages gyromitrin’s volatility, as it converts to a toxic gas when heated. While this may reduce toxin concentration, it does not eliminate it entirely. Critical factors include using ample water (at least 1 liter per 100 grams of mushrooms) and ensuring proper ventilation to disperse the toxic fumes. Even after parboiling, residual toxins can remain, making this method far from foolproof.

Another approach is drying, which some claim breaks down gyromitrin over time. However, this is a misconception; drying merely halts the toxin’s conversion to its toxic form but does not destroy it. Rehydrating dried false morels reactivates the gyromitrin, posing the same risks as fresh specimens. Moreover, the drying process must be done in a well-ventilated area to avoid inhaling toxic vapors, a hazard often overlooked by amateur foragers.

Comparatively, true morels can be safely prepared by simple cooking, as they lack these toxins. False morels, however, demand extreme caution. Even if prepared using these methods, symptoms like nausea, dizziness, or liver stress can still occur, particularly in sensitive individuals or with larger servings. The only truly safe advice is avoidance, as no preparation method can be reliably deemed risk-free. Foraging guides and mycologists uniformly recommend steering clear of false morels, emphasizing that the potential consequences far outweigh any culinary curiosity.

Mushrooms: Highly Addictive or Not?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$10.5 $22.95

$15.8 $17.99

$7.62 $14.95

Differences from True Morels

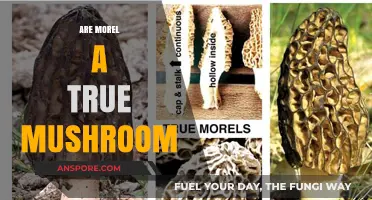

False morels, often mistaken for their edible counterparts, true morels, present a striking contrast in both appearance and toxicity. While true morels have a honeycomb-like cap with deep pits and ridges, false morels appear more brain-like, with convoluted folds and a smoother texture. This distinction is critical for foragers, as misidentification can lead to severe poisoning. True morels typically grow in deciduous forests, whereas false morels are more commonly found in coniferous areas, though this isn’t a foolproof rule. Always examine the cap structure closely: true morels have a hollow stem and cap that hang freely, while false morels often have a wrinkled, bulbous cap attached to the stem at multiple points.

From a toxicity standpoint, false morels contain gyromitrin, a water-soluble toxin that converts to monomethylhydrazine (MMH) in the body. Even small amounts of MMH can cause symptoms like nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and in severe cases, liver and kidney damage. True morels, on the other hand, are safe to eat when cooked properly. To neutralize gyromitrin, false morels must be parboiled, and the water discarded, but this method is risky and not recommended. Instead, avoid false morels entirely. If you’re unsure, consult a mycologist or use a reliable field guide. Remember, true morels have a distinct, earthy aroma, while false morels may smell faintly of chlorine or chemicals.

Foraging safely requires understanding the subtle differences in habitat. True morels often emerge in spring near elm, ash, and poplar trees, thriving in well-drained soil. False morels, however, are more adaptable, appearing under conifers or in disturbed areas. Observe the ecosystem: true morels prefer a symbiotic relationship with specific trees, while false morels are less selective. If you spot mushrooms growing in an area with mixed tree species, proceed with caution. Always cut a specimen in half to inspect the internal structure—true morels are hollow throughout, whereas false morels may have a cottony or partially solid interior.

Practical tips for differentiation include examining the stem. True morel stems are typically longer and smoother, while false morel stems are often shorter and thicker, sometimes with a brittle texture. Additionally, true morels have a more uniform color, ranging from blond to dark brown, whereas false morels may display irregular shades or a reddish tint. If you’re new to foraging, start by joining a local mycological club or attending a guided walk. Avoid consuming any mushroom unless you’re 100% certain of its identity. When in doubt, throw it out—the risk of poisoning far outweighs the culinary reward.

Lastly, consider the seasonality and geographic distribution. True morels are most abundant in spring, particularly in temperate regions of North America and Europe. False morels, however, can appear earlier in the season and are found worldwide, including in colder climates. If you’re foraging in a new area, research local species and consult regional guides. For families with children or pets, educate everyone about the dangers of false morels and emphasize the importance of not touching or tasting wild mushrooms. By focusing on these differences, you can enjoy the thrill of foraging while minimizing the risk of a toxic encounter.

Exploring the Psychedelic Journey of Fly Agaric Mushrooms Safely

You may want to see also

Long-Term Health Risks of Consumption

False morel mushrooms, often mistaken for their edible counterparts, contain a toxic compound called gyromitrin, which converts to monomethylhydrazine (MMH) in the body. While acute poisoning is well-documented, the long-term health risks of consuming these mushrooms are less understood but equally concerning. Repeated or chronic exposure to MMH, even in small amounts, can lead to cumulative toxicity, affecting multiple organ systems over time. This is particularly relevant for foragers who may inadvertently include false morels in their diet due to misidentification.

One of the most significant long-term risks is hepatotoxicity, or liver damage. MMH interferes with the liver’s ability to metabolize toxins, leading to chronic inflammation and fibrosis. Studies suggest that individuals who survive acute poisoning may still experience elevated liver enzymes for months or even years afterward. For those with pre-existing liver conditions, such as fatty liver disease or hepatitis, even a single exposure could exacerbate their condition, potentially leading to cirrhosis or liver failure. Limiting alcohol consumption and avoiding hepatotoxic medications can mitigate additional strain on the liver in these cases.

Another overlooked risk is neurotoxicity. MMH is a known neurotoxin that can cross the blood-brain barrier, causing oxidative stress and neuronal damage. Long-term exposure, even at subclinical levels, may contribute to cognitive decline, memory impairment, or peripheral neuropathy. Elderly individuals and those with pre-existing neurological conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis, are particularly vulnerable. Reducing dietary toxins and incorporating antioxidants like vitamin E or selenium may help protect neuronal health in at-risk populations.

Chronic exposure to false morels may also compromise the immune system. MMH-induced oxidative stress can dysregulate immune responses, increasing susceptibility to infections and autoimmune disorders. For instance, repeated low-dose exposure has been linked to elevated inflammatory markers in animal studies, suggesting a potential role in chronic inflammatory conditions like rheumatoid arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease. Strengthening the immune system through a balanced diet, regular exercise, and adequate sleep can counteract these effects to some extent.

Finally, there is emerging evidence of a possible link between false morel consumption and certain cancers, particularly hepatocellular carcinoma. MMH’s ability to damage DNA and disrupt cellular repair mechanisms may contribute to carcinogenesis over time. While human studies are limited, animal models have shown increased tumor incidence with prolonged exposure. Avoiding false morels entirely is the safest approach, but for those who have consumed them, regular cancer screenings and monitoring for early signs of malignancy are advisable, especially in individuals with a family history of cancer.

In summary, the long-term health risks of false morel consumption extend beyond acute poisoning, encompassing liver damage, neurotoxicity, immune dysfunction, and potential carcinogenic effects. Awareness of these risks, coupled with preventive measures such as accurate mushroom identification and dietary modifications, is crucial for safeguarding health. When in doubt, consult a mycologist or poison control center, as the consequences of misidentification can be far-reaching.

Mushroom Delicacy: Which Variety Reigns Supreme?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, false morel mushrooms (Gyromitra species) are poisonous and can cause severe illness or even death if consumed.

False morels contain a toxin called gyromitrin, which breaks down into monomethylhydrazine, a compound that damages the liver, kidneys, and nervous system.

No, simply cooking false morels does not eliminate their toxins. Proper preparation involves extensive soaking, boiling, and discarding the water multiple times, but even then, consumption is risky.

False morels have a brain-like, wrinkled appearance, while true morels have a honeycomb or sponge-like cap. False morels are toxic, whereas true morels are safe to eat when cooked.

Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness, headaches, and in severe cases, seizures, liver and kidney damage, or even death. Symptoms typically appear within 6–12 hours after ingestion.