Fungal spores play a crucial role in the reproduction and survival of fungi, serving as the primary means by which these organisms propagate and disperse. Unlike plants and animals, fungi reproduce both sexually and asexually, with spores being the key structures in both processes. Asexual spores, such as conidia and sporangiospores, are produced through mitosis and allow for rapid multiplication and colonization of new environments. Sexual spores, like asci and basidiospores, result from meiosis and genetic recombination, promoting genetic diversity and adaptability. These spores are lightweight, resilient, and often equipped with mechanisms to withstand harsh conditions, enabling fungi to spread over vast distances via air, water, or animals. Thus, fungal spores are not only essential for reproduction but also for the ecological success and persistence of fungal species.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Role in Reproduction | Fungal spores are the primary means of sexual and asexual reproduction in fungi. |

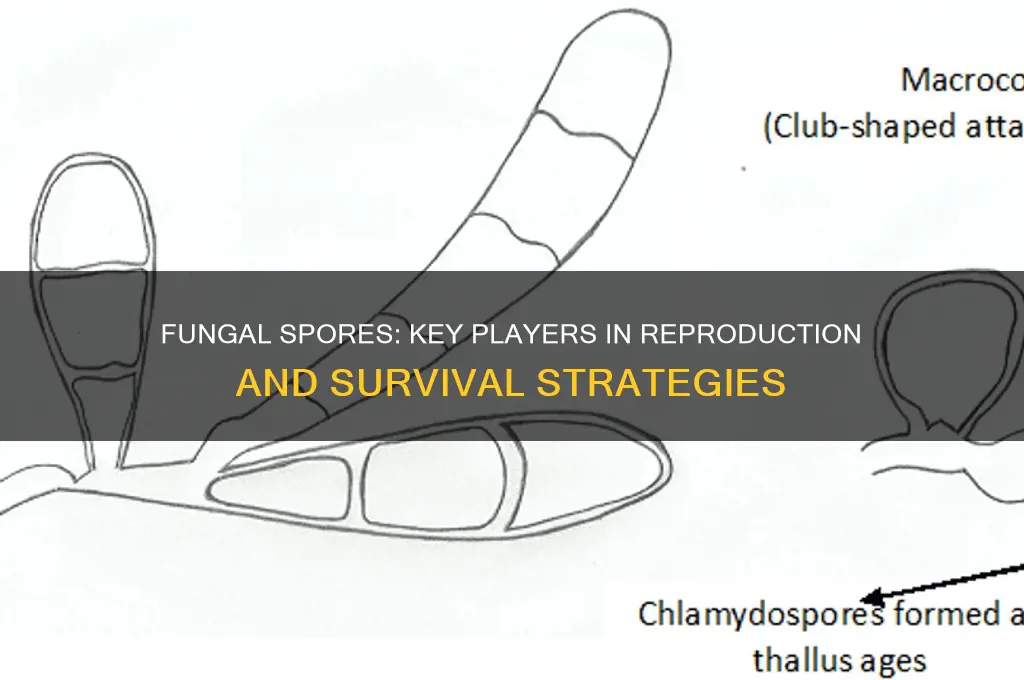

| Types of Spores | Asexual: Conidia, Sporangiospores, Chlamydospores; Sexual: Zygospores, Ascospores, Basidiospores. |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Wind, water, animals, and insects aid in spore dispersal. |

| Dormancy | Spores can remain dormant for extended periods, surviving harsh conditions. |

| Genetic Diversity | Sexual spores (e.g., ascospores, basidiospores) increase genetic diversity through meiosis and recombination. |

| Survival Structures | Asexual spores (e.g., chlamydospores) act as survival structures in adverse environments. |

| Germination | Spores germinate under favorable conditions, developing into new fungal structures. |

| Ecological Importance | Essential for fungal life cycles, decomposition, and ecosystem nutrient cycling. |

| Human Impact | Used in agriculture (e.g., mycorrhizal fungi), food production (e.g., mushrooms), and biotechnology. |

| Pathogenicity | Some spores cause diseases in plants, animals, and humans (e.g., Aspergillus, Candida). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Fungal spore types and functions

Fungal spores are diverse, each type tailored to specific environmental challenges and reproductive strategies. Broadly categorized into asexual and sexual spores, they ensure fungi’s survival across habitats. Asexual spores, like conidia and sporangiospores, are produced rapidly in favorable conditions, allowing quick colonization. Sexual spores, such as asci and basidiospores, form through genetic recombination, enhancing adaptability in harsh environments. This dual system highlights fungi’s evolutionary ingenuity in balancing speed and resilience.

Consider the conidia, asexual spores produced at the ends of specialized hyphae. Found in molds like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*, they disperse via air currents, enabling rapid spread. For instance, a single *Aspergillus* colony can release millions of conidia daily, colonizing new substrates within hours. To control their growth indoors, maintain humidity below 60% and ventilate damp areas, as conidia thrive in moist environments. This practical tip underscores the spore’s efficiency and the need for proactive management.

In contrast, basidiospores, sexual spores of mushrooms and rust fungi, exemplify precision in dispersal. Formed on club-like structures called basidia, they are ejected with force, reaching distances up to 10 cm. This mechanism ensures wide distribution, critical for fungi like *Coprinus comatus*. Gardeners can encourage basidiospore germination by mulching with organic matter, as these spores require nutrient-rich substrates to thrive. This example illustrates how spore function dictates cultivation strategies.

Zygospores, another sexual spore type, are thick-walled and resilient, formed through the fusion of hyphae in fungi like *Rhizopus*. Their durability allows them to survive extreme conditions, such as desiccation or freezing, for years. Farmers combating *Rhizopus* rot in crops should rotate storage areas and reduce humidity, as zygospores persist in soil and debris. This spore’s function as a survival structure highlights its role in fungal persistence and the challenges it poses in agricultural settings.

Understanding spore types and functions is not just academic—it’s practical. For instance, ascospores, produced in sac-like asci, are common in plant pathogens like *Magnaporthe oryzae*, causing rice blast. Farmers can reduce ascospores’ impact by planting resistant varieties and applying fungicides during spore release periods, typically early morning. This targeted approach leverages knowledge of spore behavior to mitigate crop losses. Such specificity transforms abstract biology into actionable strategies, bridging science and application.

Bread Mold Spores: Are They a Hidden Health Hazard?

You may want to see also

Role of spores in asexual reproduction

Fungal spores are not just passive agents of dispersal; they are the cornerstone of asexual reproduction in fungi, ensuring survival and proliferation across diverse environments. These microscopic structures are produced in vast quantities, enabling fungi to colonize new habitats rapidly and efficiently. Unlike sexual reproduction, which requires the fusion of gametes, asexual reproduction through spores allows fungi to reproduce from a single parent, maintaining genetic uniformity and facilitating quick adaptation to stable environments.

Consider the process of sporulation, a meticulously regulated mechanism where fungi like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* produce spores under favorable conditions. These spores, often housed in specialized structures like sporangia or conidia, are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind, water, or animals. Once released, they can remain dormant for extended periods, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate. This resilience is particularly advantageous in unpredictable ecosystems, where resources may be scarce or conditions harsh. For instance, a single *Aspergillus* colony can release millions of conidia daily, ensuring that at least some spores land in environments conducive to growth.

The role of spores in asexual reproduction is not merely about quantity but also about precision. Fungi have evolved diverse spore types, each adapted to specific ecological niches. For example, zygospores in bread molds are thick-walled and resistant to desiccation, ideal for surviving in dry environments. In contrast, basidiospores in mushrooms are equipped with a small droplet of fluid that aids in their ejection into the air, maximizing dispersal range. This specialization highlights the evolutionary sophistication of fungal spores, tailored to exploit every possible avenue for survival and propagation.

Practical applications of this knowledge are vast, particularly in agriculture and medicine. Farmers can manipulate environmental conditions to suppress spore germination in pathogenic fungi, reducing crop losses. For instance, maintaining low humidity levels can inhibit the germination of *Botrytis cinerea* spores, a common cause of gray mold in vineyards. Conversely, understanding spore behavior can enhance the cultivation of beneficial fungi, such as *Trichoderma*, which are used as biocontrol agents against plant diseases. By controlling factors like temperature, light, and nutrient availability, growers can optimize spore production and efficacy.

In conclusion, the role of spores in asexual reproduction is a testament to the adaptability and efficiency of fungi. These structures are not just means of dispersal but sophisticated tools for survival, each designed to thrive in specific conditions. By studying their mechanisms, we unlock practical strategies for managing fungal populations, whether to combat pathogens or harness their benefits. The humble spore, often overlooked, is indeed a powerhouse of fungal biology.

Are Dry Mold Spores Dangerous? Understanding Health Risks and Safety

You may want to see also

Sexual reproduction via spore formation

Fungal spores are not merely agents of asexual reproduction; they also play a pivotal role in sexual reproduction, a process that ensures genetic diversity and adaptability in fungi. Unlike asexual spores, which are clones of the parent organism, sexual spores result from the fusion of gametes, introducing genetic recombination. This mechanism is particularly crucial for fungi to survive in changing environments, as it allows for the emergence of new traits that may confer advantages such as resistance to pathogens or tolerance to extreme conditions.

The process of sexual reproduction via spore formation typically begins with the interaction of compatible fungal individuals, often signaled by environmental cues like nutrient availability or temperature changes. For example, in basidiomycetes (e.g., mushrooms), hyphae from two compatible mates fuse, forming a dikaryotic mycelium where two haploid nuclei coexist in a single cell. This stage is followed by the development of specialized structures like basidiocarps, where meiosis occurs, leading to the formation of haploid basidiospores. These spores are then dispersed, capable of germinating into new individuals under favorable conditions.

One of the most fascinating aspects of this process is its efficiency in promoting genetic diversity. In ascomycetes (e.g., yeasts and molds), sexual reproduction involves the formation of asci, sac-like structures that contain ascospores. The fusion of haploid cells (gametangia) results in a diploid zygote, which undergoes meiosis to produce haploid ascospores. This cycle not only ensures genetic variation but also allows fungi to colonize new habitats rapidly. For instance, *Neurospora crassa*, a model organism in genetics, uses this mechanism to adapt to diverse ecological niches.

Practical applications of understanding sexual spore formation extend to agriculture and medicine. Farmers can manipulate environmental conditions to encourage sexual reproduction in beneficial fungi, enhancing soil health and crop yields. Conversely, controlling sexual reproduction in pathogenic fungi can mitigate diseases in plants and humans. For example, disrupting the mating signals of *Magnaporthe oryzae*, a rice pathogen, has shown promise in reducing crop losses. Similarly, antifungal drugs targeting sexual spore formation pathways could offer new strategies for treating fungal infections in humans.

In conclusion, sexual reproduction via spore formation is a sophisticated and essential process in the fungal life cycle. By fostering genetic diversity, it enables fungi to thrive in diverse environments and adapt to challenges. Whether in ecological balance, agricultural productivity, or medical advancements, understanding this mechanism provides valuable insights and practical tools for harnessing the potential of fungi.

Where to Legally Obtain Psilocybin Spores for Research and Cultivation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental triggers for spore release

Fungal spores are not merely passive agents of reproduction; their release is a highly regulated process influenced by specific environmental cues. Understanding these triggers is crucial for both ecological studies and practical applications, such as controlling fungal pathogens in agriculture or harnessing fungi for biotechnology. Among the most significant environmental factors are humidity, light, temperature, and nutrient availability, each playing a distinct role in signaling the optimal time for spore dispersal.

Consider humidity, a primary trigger for many fungal species. For instance, the ascomycete *Botrytis cinerea*, a notorious plant pathogen, initiates spore release under high humidity conditions, typically above 90%. This response is adaptive, as moisture facilitates spore adhesion to surfaces and subsequent germination. In contrast, some basidiomycetes, like the mushroom *Coprinus comatus*, release spores in drier conditions, often after a rain event has provided sufficient moisture for initial growth but before humidity levels drop too low. Monitoring humidity levels in agricultural settings can thus help predict and mitigate fungal outbreaks by timing interventions, such as fungicide application, during periods of heightened spore release.

Light exposure is another critical factor, particularly for fungi inhabiting surface environments. Many species, including *Neurospora crassa*, exhibit phototropic responses, releasing spores during specific light cycles. For example, *N. crassa* disperses spores in the early morning, coinciding with the transition from darkness to light. This behavior is regulated by photoreceptors that detect blue light, a mechanism shared by numerous fungi. For indoor fungal cultivation or containment, manipulating light exposure—such as using blue light filters or controlling photoperiods—can suppress unwanted spore release, reducing contamination risks in laboratories or grow rooms.

Temperature fluctuations also act as a potent trigger, often in conjunction with other factors. The human pathogen *Aspergillus fumigatus* releases spores in response to temperatures between 37°C and 50°C, a range that mimics the conditions of its natural habitat, including decomposing organic matter and mammalian hosts. In industrial settings, maintaining temperatures outside this range can limit spore dispersal, particularly in HVAC systems where *A. fumigatus* is a common contaminant. Similarly, in natural ecosystems, seasonal temperature shifts signal fungi like *Puccinia graminis* (the cause of wheat rust) to release spores, aligning with the growth cycles of their host plants.

Nutrient availability provides a final, often overlooked, environmental cue. Some fungi, such as *Trichoderma* species, release spores when nutrient levels in their substrate decline, ensuring dispersal to new resource-rich areas. This behavior is exploited in biocontrol applications, where *Trichoderma* is used to outcompete plant pathogens. By manipulating nutrient concentrations in soil or growth media, farmers and researchers can encourage beneficial spore release while suppressing harmful species. For instance, reducing nitrogen levels in soil has been shown to stimulate spore production in certain *Trichoderma* strains, enhancing their efficacy as biological control agents.

In summary, environmental triggers for spore release are diverse and species-specific, reflecting fungi’s adaptability to their habitats. By identifying and manipulating these cues—humidity, light, temperature, and nutrients—we can better manage fungal populations in agriculture, medicine, and industry. Whether through predictive modeling, environmental control, or targeted interventions, understanding these triggers transforms our ability to harness or hinder fungal reproduction, depending on the context.

Exploring the Microscopic World: What Does a Spore Really Look Like?

You may want to see also

Spore dispersal mechanisms in fungi

Fungi rely on spores as their primary means of reproduction and dispersal, ensuring survival across diverse environments. These microscopic units are lightweight, durable, and produced in vast quantities, enabling fungi to colonize new habitats efficiently. However, the success of this strategy hinges on effective dispersal mechanisms, which vary widely among fungal species. From passive methods like wind and water to active strategies involving explosive force or animal vectors, each mechanism is finely tuned to the fungus’s ecological niche.

Consider the *Puffball* fungus, a master of passive dispersal. When mature, its fruiting body develops internal pressure until it ruptures, releasing a cloud of spores into the air. This process, known as "puffballing," relies on wind currents to carry spores over long distances. Similarly, *Aspergillus* species use a spring-like mechanism called a sterigma to launch spores with precision, though their dispersal still depends on external air movement. For optimal spore release, gardeners and mycologists should avoid disturbing puffball fungi during their mature stage, as even slight pressure can trigger premature discharge.

In contrast, some fungi employ active mechanisms that eliminate reliance on external forces. The *Pilobolus* fungus, for instance, uses a phototropic sporangiophore to aim its spore-containing structure toward light sources, typically the forest canopy. Upon reaching maturity, the sporangium bursts, propelling spores up to 2 meters with an internal pressure of approximately 1.5 atmospheres. This targeted approach ensures spores land in environments favorable for growth. Researchers studying such mechanisms often use controlled light sources to observe and measure spore trajectories.

Water serves as another critical dispersal medium, particularly for aquatic and semi-aquatic fungi. Species like *Chytridiomycota* produce motile spores called zoospores, equipped with flagella for swimming. These spores can travel short distances in water, colonizing new substrates efficiently. In agricultural settings, managing water flow is essential to prevent the spread of chytrid fungi, which can cause crop diseases. For example, reducing standing water and improving drainage can limit zoospore mobility.

Animal vectors also play a significant role in spore dispersal, particularly for fungi associated with dung or decaying matter. Spores of *Coprinus comatus* (the shaggy mane mushroom) often adhere to the fur or feet of small mammals, hitching a ride to new locations. Similarly, insects visiting fungi for nutrients inadvertently carry spores on their bodies. To encourage beneficial fungi in gardens, planting insect-attracting flowers near fungal habitats can enhance spore dispersal.

Understanding these mechanisms not only sheds light on fungal ecology but also informs practical applications. For instance, mycologists can mimic natural dispersal methods to cultivate fungi more effectively, while farmers can implement targeted strategies to control pathogenic species. By studying spore dispersal, we gain insights into the resilience and adaptability of fungi, one of nature’s most successful life forms.

Is Milky Spore Safe for Dogs? A Pet Owner's Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, fungal spores are a primary means of reproduction in fungi. They are specialized cells produced by fungi to disperse and form new individuals under favorable conditions.

Fungal spores are released into the environment and, when conditions are right (e.g., moisture, temperature), they germinate and grow into new fungal organisms, ensuring the species' survival and spread.

Fungal spores can be involved in both sexual and asexual reproduction, depending on the species. Some fungi produce spores through meiosis (sexual) for genetic diversity, while others produce spores through mitosis (asexual) for rapid multiplication.