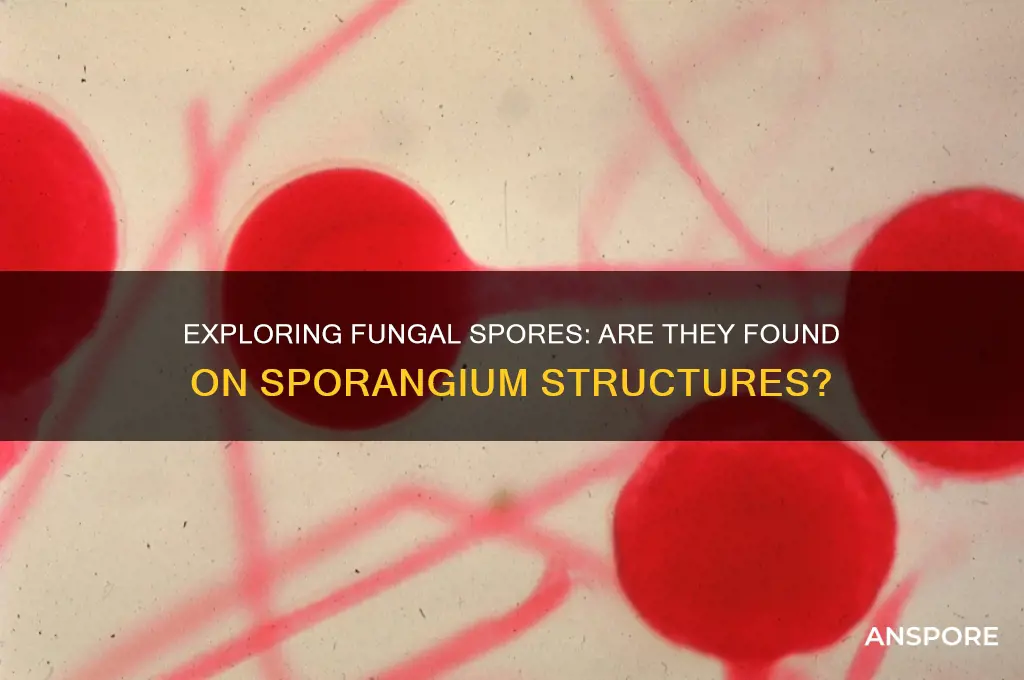

Fungal spores are essential structures for the reproduction and dispersal of fungi, and understanding their location is crucial for studying fungal biology. One key structure associated with spore production is the sporangium, a sac-like organ found in certain types of fungi, particularly in zygomycetes and some oomycetes. The sporangium serves as a site for spore development and containment, raising the question: are fungal spores indeed found on or within the sporangium? This inquiry delves into the anatomical relationship between fungal spores and the sporangium, shedding light on the mechanisms of spore formation, maturation, and release in these organisms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Location of Fungal Spores | Fungal spores are indeed found on sporangia. Sporangia are structures produced by certain fungi (primarily zygomycetes and some ascomycetes) that contain and release spores. |

| Type of Spores | Sporangiospores are the type of spores produced within sporangia. These spores are typically asexual and are formed through mitosis. |

| Function of Sporangium | The primary function of a sporangium is to protect and disperse spores. Once mature, the sporangium ruptures or opens to release the spores into the environment. |

| Shape and Structure | Sporangia can vary in shape (e.g., spherical, oval) and structure depending on the fungal species. They are often borne at the tips of specialized hyphae called sporangiophores. |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Spores are dispersed through various mechanisms, including wind, water, or animals, once released from the sporangium. |

| Examples of Fungi | Fungi like Rhizopus (bread mold) and Mucor are well-known examples where sporangia and sporangiospores are prominent features. |

| Life Cycle Role | Sporangiospores play a key role in the asexual reproduction and survival of fungi, allowing them to colonize new environments rapidly. |

| Comparison with Other Structures | Unlike asci (in ascomycetes) or basidia (in basidiomycetes), sporangia are not involved in sexual reproduction but are strictly asexual structures. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Sporangium structure and function

Fungal spores are indeed found on sporangia, which serve as critical reproductive structures in certain fungi. The sporangium, a sac-like organ, plays a pivotal role in the life cycle of spore-producing fungi, particularly in zygomycetes and some other groups. Understanding its structure and function is essential to grasp how these organisms disseminate and survive in diverse environments.

Structurally, a sporangium is a spherical or oval-shaped structure typically located at the tip of a sporangiophore, a specialized hyphal stalk. Its wall is composed of multiple layers of cells that provide protection and support. Inside, the sporangium houses numerous haploid spores, which are the primary means of asexual reproduction in these fungi. The arrangement and development of these spores within the sporangium vary among species, but they are generally produced through mitosis, ensuring genetic uniformity. For instance, in *Rhizopus*, a common bread mold, the sporangium can contain thousands of spores, each capable of germinating under favorable conditions.

Functionally, the sporangium acts as both a spore factory and a dispersal unit. Once mature, the sporangium wall dries and ruptures, releasing the spores into the environment. This process is often facilitated by environmental cues such as air currents, water, or physical disturbance. The lightweight nature of the spores allows them to travel significant distances, increasing the fungus’s chances of colonizing new habitats. For example, in agricultural settings, sporangial spores of *Sclerotinia* species can spread rapidly, causing devastating crop diseases if not managed promptly.

To optimize spore release, some fungi have evolved mechanisms to enhance dispersal efficiency. For instance, the sporangia of *Pilobolus*, a fungus found on herbivorous animal dung, use a unique "cannon mechanism" where internal pressure builds up, propelling the sporangium toward light sources, often vegetation, ensuring spores land in nutrient-rich environments. This adaptation highlights the sporangium’s role not just as a spore container but as a sophisticated dispersal tool.

In practical terms, understanding sporangium structure and function is crucial for controlling fungal pathogens. For example, in greenhouses, reducing humidity and improving air circulation can inhibit sporangium maturation and spore release, mitigating the spread of molds like *Botrytis*. Similarly, in medical settings, knowing that sporangia of *Mucor* species can produce spores that cause invasive infections in immunocompromised patients underscores the importance of environmental hygiene and early detection. By targeting the sporangium, fungicides and preventive measures can be more effective, disrupting the fungal life cycle at its reproductive core.

Understanding Spore Ploidy: Haploid or Diploid in Fungi and Plants

You may want to see also

Fungal spore formation process

Fungal spores are indeed found on sporangia, which serve as the primary structures for spore production in many fungi. This relationship is fundamental to understanding the fungal spore formation process, a complex yet fascinating mechanism that ensures the survival and dispersal of fungal species. The sporangium, a sac-like structure, houses the spores until they are ready for release, playing a critical role in the life cycle of fungi.

The formation of fungal spores begins with the development of sporangia, typically at the tips of specialized hyphae called sporangiophores. Within the sporangium, spores are produced through a process known as sporogenesis. This involves the division of cells via meiosis, resulting in haploid spores that are genetically diverse. For example, in the bread mold *Rhizopus*, sporangia can contain thousands of spores, each capable of developing into a new fungal organism under favorable conditions. The efficiency of this process highlights the adaptability of fungi to various environments.

One of the most intriguing aspects of spore formation is the precision with which fungi regulate this process. Environmental cues such as light, temperature, and nutrient availability trigger the initiation of sporulation. For instance, in *Phycomyces*, exposure to blue light accelerates sporangium development, demonstrating how fungi respond to external stimuli to optimize spore production. This sensitivity to environmental factors ensures that spores are released when conditions are most conducive to their survival and germination.

Practical applications of understanding spore formation extend to fields like agriculture and medicine. Farmers can manipulate environmental conditions to control fungal growth, reducing crop losses caused by spore-borne pathogens. For example, maintaining lower humidity levels can inhibit sporangium development in molds like *Botrytis cinerea*, which affects grapes and strawberries. Similarly, in medical settings, knowledge of spore formation aids in the development of antifungal treatments that target specific stages of the sporulation process, potentially disrupting fungal proliferation.

In conclusion, the fungal spore formation process is a highly regulated and environmentally responsive mechanism centered around the sporangium. By studying this process, we gain insights into fungal biology and develop strategies to manage fungi in various contexts. Whether in a laboratory, field, or clinical setting, understanding how and where spores are formed is essential for harnessing or controlling fungal activity effectively.

Are Clostridium Botulinum Spores Toxic? Uncovering the Truth and Risks

You may want to see also

Types of fungal spores in sporangia

Fungal spores are indeed found within sporangia, which are specialized structures produced by certain fungi for the purpose of spore dispersal. These spores are not uniform; they vary significantly in type, function, and the mechanisms by which they are released. Understanding these variations is crucial for fields like mycology, agriculture, and medicine, as different spore types can have distinct impacts on ecosystems and human health.

Analytical Perspective:

Sporangia house two primary types of fungal spores: endospores and exospores. Endospores, such as those produced by Zygomycota, develop internally within the sporangium and are released only after the structure ruptures. Exospores, in contrast, form on the outer surface of the sporangium, as seen in some Oomycota species. The distinction lies in their developmental location and release mechanism. For instance, endospores are often dispersed en masse, relying on environmental factors like wind or water to break open the sporangium, while exospores may detach individually, allowing for more targeted dispersal.

Instructive Approach:

To identify spore types, examine the sporangium under a microscope at 400x magnification. Look for the presence of a thick-walled sporangium, which typically indicates endospores. For exospores, observe if the spores are attached to the sporangium’s exterior. A practical tip: staining the sample with lactophenol cotton blue enhances visibility, making it easier to differentiate between spore types and their developmental stages.

Comparative Analysis:

While both endospores and exospores serve reproductive purposes, their ecological roles differ. Endospores are more common in terrestrial fungi, where mass dispersal is advantageous for colonizing new habitats. Exospores, however, are prevalent in aquatic or semi-aquatic fungi, where individual spore release aligns with the need to navigate water currents. This comparison highlights how spore type is often adapted to the fungus’s environment, influencing its survival and propagation strategies.

Descriptive Insight:

Imagine a sporangium as a microscopic balloon filled with endospores, each spore a tiny, resilient capsule waiting to be released. In contrast, exospores resemble buds on a branch, ready to detach and drift away independently. This visual analogy underscores the structural and functional diversity of fungal spores, which are as varied as the fungi that produce them. For example, the sporangia of *Physarum polycephalum* (a slime mold) produce endospores that are dispersed explosively, while those of *Achlya* (a water mold) bear exospores that gently detach into the water.

Persuasive Argument:

Understanding the types of fungal spores in sporangia is not just academic—it has practical implications. For farmers, knowing whether a fungal pathogen produces endospores or exospores can inform control strategies, such as using windbreaks to limit mass dispersal or water management to reduce individual spore spread. For researchers, this knowledge aids in developing targeted antifungal treatments, as spore type can influence susceptibility to environmental stressors or chemicals. By focusing on these specifics, we can better manage fungal populations and mitigate their negative impacts.

How Liverworts Reproduce: Unveiling Their Sporic Life Cycle Secrets

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Sporangium location on fungal organisms

Fungal spores are indeed found on sporangia, which serve as the primary structures for spore production and dispersal in many fungal organisms. The sporangium, a sac-like structure, is a critical component in the life cycle of fungi, particularly in those belonging to the phylum Zygomycota and certain groups of Chytridiomycota. Understanding the location of sporangia on fungal organisms is essential for identifying fungal species, studying their reproductive strategies, and managing fungal diseases in agriculture and medicine.

Strategic Placement for Optimal Dispersal

The location of sporangia on fungal organisms is strategically optimized for spore dispersal. In Zygomycetes, such as *Rhizopus* and *Mucor*, sporangia are typically borne at the tips of specialized hyphae called sporangiophores. These elevated structures ensure that spores are released into air currents, maximizing their reach. For instance, in *Rhizopus stolonifer*, the black bread mold, sporangia are prominently displayed on tall, erect sporangiophores, allowing spores to disperse widely and colonize new substrates efficiently. This placement is a testament to the fungus’s adaptation to its environment, ensuring survival and propagation.

Comparative Analysis Across Fungal Groups

While sporangia in Zygomycetes are often terminally located, other fungal groups exhibit different arrangements. In Chytridiomycetes, the simplest fungi, sporangia may form directly on thalli or rhizoids, often in aquatic environments. This contrasts with the elevated sporangia of Zygomycetes, reflecting the Chytridiomycetes’ reliance on water for spore dispersal. In contrast, some Oomycetes (often mistakenly classified as fungi) produce sporangia on branching structures called sporangiophores, similar to Zygomycetes, but their spores are typically zoospores, which swim rather than being wind-dispersed. These variations highlight the diversity in sporangium location and function across fungal lineages.

Practical Implications for Fungal Management

Knowledge of sporangium location is invaluable in practical applications, particularly in controlling fungal pathogens. For example, in agricultural settings, understanding that sporangia in *Rhizopus* are elevated on sporangiophores can inform strategies for reducing spore dispersal, such as increasing air filtration in greenhouses or using fungicides targeted at these structures. Similarly, in medical mycology, recognizing the location of sporangia in opportunistic pathogens like *Mucor* can aid in diagnosing and treating mucormycosis, a severe fungal infection. For instance, surgical debridement of infected tissue may focus on areas where sporangia are densely clustered to prevent further spore release.

Descriptive Insights into Sporangium Development

The development of sporangia is a fascinating process that varies depending on their location. In Zygomycetes, sporangia form through the swelling of a hyphal tip, followed by the production of spores within the sac. The sporangium wall then ruptures, releasing the spores into the environment. In contrast, Chytridiomycetes often produce sporangia through the enlargement of a single cell, which eventually releases zoospores. Observing these developmental stages under a microscope can provide critical insights into fungal reproduction and life cycles. For hobbyists or students, a simple experiment involves culturing *Rhizopus* on bread and observing the development of sporangia over 2–3 days, noting their location and structure.

Takeaway for Fungal Enthusiasts and Professionals

In summary, the location of sporangia on fungal organisms is a key feature that reflects their reproductive strategy and ecological niche. Whether elevated on sporangiophores in Zygomycetes or directly on thalli in Chytridiomycetes, this placement is crucial for spore dispersal and fungal survival. For enthusiasts, understanding sporangium location enhances appreciation of fungal diversity, while for professionals, it informs practical strategies for fungal management. By studying these structures, we gain deeper insights into the intricate world of fungi and their impact on ecosystems, agriculture, and human health.

Unveiling the Unique Appearance of Morel Spores: A Visual Guide

You may want to see also

Environmental factors affecting spore release

Fungal spores are indeed found on sporangia, which are structures produced by certain fungi to house and disperse these spores. However, the release of these spores is not a random event; it is heavily influenced by environmental factors that trigger or inhibit their dispersal. Understanding these factors is crucial for managing fungal populations, whether in agricultural settings, natural ecosystems, or indoor environments.

Humidity and Moisture: The Double-Edged Sword

Moisture is a primary driver of spore release, but its effect varies depending on the fungal species. For instance, many basidiomycetes, like those causing wood rot, release spores in high humidity (above 90%) to ensure they adhere to surfaces and germinate effectively. Conversely, dry conditions can force some fungi, such as *Aspergillus* species, to release spores prematurely as a survival mechanism. Practical tip: In greenhouses, maintaining relative humidity below 80% can reduce spore release from common pathogens like *Botrytis cinerea*, but avoid dropping it below 50% to prevent stress-induced dispersal.

Temperature: Timing is Everything

Temperature acts as a cue for spore release, often synchronized with seasonal changes. For example, *Alternaria* spores, common allergens and crop pathogens, are released in warm temperatures (25–30°C), while cold-tolerant fungi like *Fusarium* may disperse spores in cooler conditions (15–20°C). Caution: Sudden temperature fluctuations, such as those caused by heating systems in indoor environments, can trigger unexpected spore release, exacerbating allergies or mold growth.

Light and Photoperiod: The Hidden Regulator

Light exposure and photoperiod (day length) influence spore release in many fungi. For instance, *Neurospora crassa*, a model fungus, releases spores in response to light, particularly blue wavelengths (450–470 nm). In natural settings, this aligns spore dispersal with dawn, maximizing wind-driven spread. Comparative insight: Unlike plants, which often use light for growth, fungi use it as a signal for reproduction, making light control a potential tool for managing spore release in enclosed spaces.

Wind and Airflow: The Dispersal Mechanism

Wind is the primary agent for spore dispersal, but its effectiveness depends on spore size and environmental conditions. Small spores (1–5 μm), like those of *Cladosporium*, are easily carried over long distances, while larger spores (10–20 μm), such as those of *Ganoderma*, require stronger gusts. Instructive tip: In agricultural fields, reducing wind speed with windbreaks can limit spore spread, but ensure adequate airflow to prevent moisture buildup, which could promote fungal growth.

Nutrient Availability: The Survival Imperative

Spore release is often triggered when nutrients in the substrate are depleted, forcing the fungus to disperse its offspring. For example, *Penicillium* species release spores when carbon sources are exhausted. Analytical takeaway: In indoor environments, removing organic debris and reducing dust can deprive fungi of nutrients, delaying spore release and minimizing mold risks.

By manipulating these environmental factors, it is possible to control spore release, whether to protect crops, improve indoor air quality, or study fungal behavior. Each factor interacts with others, creating a complex web of influences that requires tailored strategies for effective management.

Best Places to Purchase Morel Mushroom Spores for Cultivation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, fungal spores are often found on or within the sporangium, a structure produced by certain fungi to contain and release spores.

The sporangium serves as a reproductive structure in fungi, housing and dispersing spores to facilitate the spread and survival of the organism.

No, not all fungi produce spores on a sporangium. This structure is specific to certain groups of fungi, such as zygomycetes and some other lower fungi.

Spores are typically released from the sporangium through rupture or opening of the structure, often triggered by environmental factors like wind, rain, or physical disturbance.

While most fungal spores from a sporangium are harmless, some species can cause infections in humans, particularly in individuals with weakened immune systems.