Fungi are a diverse group of organisms that play crucial roles in ecosystems, from decomposing organic matter to forming symbiotic relationships with plants. One of the most distinctive features of fungi is their method of reproduction, which primarily involves the production and dispersal of spores. Spores are microscopic, single-celled or multicellular structures that serve as the primary means of propagation for most fungi. These spores are highly resilient, capable of surviving harsh environmental conditions, and can be dispersed through air, water, or animals. Once they land in a suitable environment, spores germinate and grow into new fungal individuals, ensuring the continuation of the species. This efficient and widespread method of reproduction highlights the adaptability and ecological significance of fungi in various habitats.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Propagation Method | Fungi are primarily propagated by spores. |

| Types of Spores | Sexual (e.g., zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores) and asexual (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores, zoospores). |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Air, water, animals, insects, and human activities. |

| Survival Strategy | Spores are highly resistant to harsh environmental conditions, allowing fungi to survive in diverse habitats. |

| Germination | Spores germinate under favorable conditions, such as adequate moisture, temperature, and nutrients. |

| Role in Life Cycle | Spores are essential for reproduction and dispersal, ensuring the continuation of fungal species. |

| Diversity | Fungi produce vast numbers of spores, contributing to their widespread distribution and ecological success. |

| Ecological Importance | Spores play a key role in nutrient cycling, decomposition, and symbiotic relationships in ecosystems. |

| Human Impact | Fungal spores can cause allergies, diseases, and food spoilage but are also used in biotechnology and agriculture. |

Explore related products

$13.99 $17.99

What You'll Learn

Types of fungal spores

Fungi are indeed propagated by spores, which serve as their primary means of reproduction and dispersal. These microscopic structures are lightweight, resilient, and capable of surviving harsh conditions, ensuring the survival and spread of fungal species across diverse environments. Among the various types of fungal spores, each plays a unique role in the life cycle and ecological impact of fungi.

Sporangiospores, for instance, are produced within a structure called a sporangium and are commonly found in zygomycetes, such as black bread mold (*Rhizopus*). These spores are formed through asexual reproduction and are released en masse, often dispersed by air currents. To observe sporangiospores, one can grow *Rhizopus* on a slice of bread and notice the black, powdery spores that develop within 24–48 hours. A practical tip: avoid inhaling these spores, as they can cause allergic reactions or infections in immunocompromised individuals.

In contrast, conidia are asexual spores produced at the tips or sides of specialized hyphae called conidiophores. Found in fungi like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*, conidia are single-celled and highly adaptable, allowing rapid colonization of new substrates. For example, *Aspergillus niger* produces conidia that can contaminate food and damp indoor environments. To prevent conidial growth, maintain humidity levels below 60% and promptly address water leaks or dampness in buildings.

Ascospores and basidiospores are sexual spores, formed in asci and basidia, respectively. Ascospores, characteristic of sac fungi (e.g., *Neurospora*), are often eight per ascus and are released through a pore or slit. Basidiospores, found in mushrooms and rust fungi, are typically produced on club-shaped basidia and are dispersed by wind or water. Foraging enthusiasts should note that while many basidiomycetes are edible, proper identification is crucial, as some species are toxic. A cautionary step: always consult a field guide or expert before consuming wild mushrooms.

Finally, zygospores are thick-walled, sexual spores formed through the fusion of gametangia in zygomycetes. These spores are highly resistant to environmental stresses, such as desiccation and extreme temperatures, enabling long-term survival in soil. While zygospores are less commonly encountered than other spore types, their resilience underscores the adaptability of fungi. For gardeners, understanding zygospore persistence can inform soil management practices, such as crop rotation to reduce fungal pathogens.

In summary, the diversity of fungal spores—sporangiospores, conidia, ascospores, basidiospores, and zygospores—reflects the varied reproductive strategies and ecological roles of fungi. Each spore type is tailored to specific environmental conditions and dispersal mechanisms, ensuring the widespread success of fungi in nearly every habitat on Earth.

Understanding Mold Spores Lifespan: How Long Do They Survive?

You may want to see also

Sporulation process in fungi

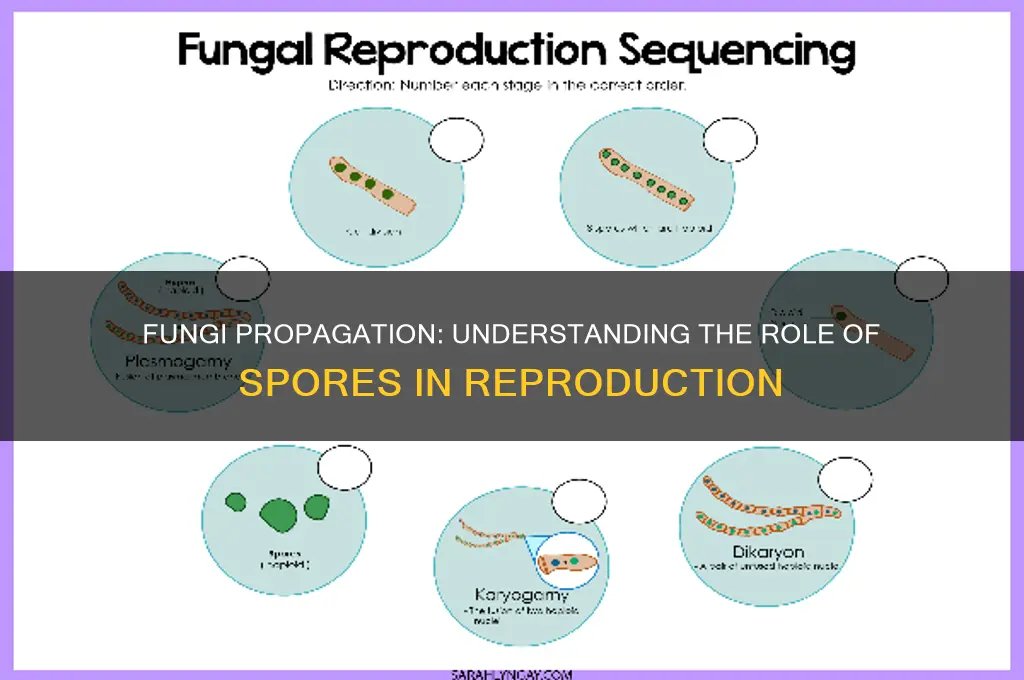

Fungi are indeed propagated by spores, a fact that underscores their remarkable adaptability and survival strategies. The sporulation process is a complex, highly regulated mechanism that ensures the dissemination and longevity of fungal species across diverse environments. This process is not merely a means of reproduction but a sophisticated response to environmental cues, enabling fungi to thrive in conditions that would be inhospitable to many other organisms.

The Sporulation Process: A Step-by-Step Overview

Sporulation begins with the detection of environmental stressors such as nutrient depletion, desiccation, or overcrowding. In response, fungal cells undergo a series of morphological and metabolic changes. For example, in *Aspergillus* species, the process starts with the formation of a structure called a vesicle, which develops into a sterigma and ultimately produces conidia—asexual spores. In contrast, basidiomycetes like mushrooms form basidiospores on club-shaped structures called basidia. Each step is tightly controlled by genetic and biochemical pathways, ensuring precision in spore development.

Environmental Triggers and Optimal Conditions

Sporulation is highly sensitive to environmental factors. For instance, light exposure can induce sporulation in certain fungi, such as *Neurospora crassa*, which uses photoreceptors to initiate the process. Temperature also plays a critical role; many fungi sporulate optimally at temperatures between 25°C and 30°C. Humidity levels are equally important, as spores require a balance of moisture to develop without becoming waterlogged. Practical tip: For laboratory cultivation, maintaining a relative humidity of 85–90% and a temperature of 28°C can enhance sporulation efficiency in species like *Penicillium*.

Comparative Analysis: Asexual vs. Sexual Sporulation

Asexual sporulation, such as the production of conidia or spores, is faster and more common, allowing fungi to rapidly colonize new areas. However, sexual sporulation, which involves the fusion of gametes and the formation of structures like asci or basidia, produces genetically diverse spores that enhance survival in changing environments. For example, the sexual spores of *Fusarium* species are more resilient to harsh conditions than their asexual counterparts. This duality highlights the evolutionary advantage of fungi, balancing speed and adaptability.

Practical Applications and Cautions

Understanding sporulation is crucial in fields like agriculture, medicine, and biotechnology. For instance, controlling sporulation in plant pathogens can reduce crop diseases, while harnessing spore production in beneficial fungi like *Trichoderma* can enhance biocontrol strategies. However, caution is necessary when handling fungal spores, as they can be allergens or pathogens. For example, *Aspergillus fumigatus* spores can cause invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised individuals. Always use personal protective equipment, such as HEPA filters and gloves, when working with fungal cultures.

Takeaway: The Elegance of Sporulation

The sporulation process in fungi is a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. By responding to environmental cues with precision and producing spores that are both resilient and diverse, fungi ensure their survival across ecosystems. Whether in a laboratory setting or the natural world, understanding this process unlocks opportunities for innovation while demanding respect for its potential risks.

Effective Ways to Purify Air and Eliminate Mold Spores Safely

You may want to see also

Environmental factors affecting spore release

Fungi rely on spore release for propagation, but this process is not random. Environmental factors act as conductors, orchestrating the timing and intensity of spore dispersal. Understanding these factors is crucial for managing fungal populations, whether in agriculture, forestry, or indoor environments.

Let's delve into the key environmental players and their impact.

Humidity: The Triggering Mist

High humidity acts as a primary trigger for spore release in many fungi. Think of it as a signal to the fungus that conditions are favorable for germination. Spores, being lightweight and often hydrophobic, are easily carried by water vapor, increasing their chances of reaching suitable substrates. For example, the common mold *Aspergillus* releases spores in response to humidity levels above 70%. In controlled environments like greenhouses, maintaining humidity below this threshold can significantly reduce spore dispersal and subsequent fungal growth.

Temperature: The Metronome of Release

Temperature plays a dual role in spore release. Some fungi, like the notorious *Fusarium*, exhibit optimal spore discharge at specific temperature ranges, often correlating with their preferred growth conditions. Others, like certain species of *Penicillium*, may release spores over a wider temperature range but with varying intensity. Understanding these temperature preferences allows for targeted interventions. For instance, lowering temperatures in storage facilities can suppress spore release in fungi that thrive in warmer conditions.

Light: A Subtle Influencer

While less direct than humidity and temperature, light can also influence spore release. Some fungi are phototropic, meaning they respond to light stimuli. For example, certain species of *Alternaria*, a common plant pathogen, release spores in response to blue light. This knowledge can be leveraged in agricultural settings by manipulating light exposure to disrupt spore dispersal patterns and reduce disease incidence.

Airflow: The Dispersal Highway

Air movement is essential for spore dispersal. Still air limits the distance spores can travel, while even gentle breezes can carry them over considerable distances. In indoor environments, proper ventilation is crucial for preventing spore accumulation and subsequent fungal growth. In agricultural settings, windbreaks can be strategically placed to reduce the spread of fungal pathogens from infected plants to healthy ones.

Practical Takeaways

By understanding these environmental factors, we can implement targeted strategies to manage fungal spore release. This includes:

- Humidity Control: Maintaining optimal humidity levels in indoor spaces and storage facilities.

- Temperature Regulation: Adjusting temperatures to discourage spore release from specific fungal species.

- Light Manipulation: Utilizing light spectra to disrupt spore discharge in phototropic fungi.

- Airflow Management: Ensuring adequate ventilation and employing windbreaks to control spore dispersal.

These measures, informed by the intricate relationship between fungi and their environment, empower us to mitigate the impact of fungal spores and promote healthier ecosystems.

Shroomish's Spore Move: When and How to Unlock It

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Methods of spore dispersal

Fungi are indeed propagated by spores, and their dispersal methods are as diverse as the fungi themselves. These microscopic units of reproduction are lightweight and numerous, allowing fungi to colonize new environments efficiently. Understanding how spores are dispersed is crucial for both ecological studies and practical applications, such as controlling fungal diseases in agriculture.

One of the most common methods of spore dispersal is wind. Fungi like mushrooms and molds produce spores in vast quantities, often releasing them into the air in a process called ballistospore discharge. For example, the common puffball fungus ejects spores at speeds up to 70 miles per hour, ensuring they travel far and wide. Wind dispersal is particularly effective for fungi in open environments, where air currents can carry spores over long distances. To maximize this method, some fungi have evolved spore-bearing structures, such as gills or pores, that are positioned to catch the wind.

Water is another key player in spore dispersal, especially for aquatic and soil-dwelling fungi. Spores of water molds, like those in the genus *Phytophthora*, are often dispersed by rain splash or flowing water. In agricultural settings, this can lead to rapid spread of diseases like late blight in potatoes. Gardeners and farmers can mitigate this by ensuring proper drainage and avoiding overhead watering, which can dislodge spores and spread them to healthy plants.

Animals and humans also contribute to spore dispersal, often unintentionally. Zoospores, motile spores propelled by flagella, can swim to new locations, but many fungi rely on larger creatures. Spores can attach to the fur or feathers of animals, or even to human clothing and tools, hitching a ride to new habitats. For instance, truffle spores are dispersed by animals that dig up and eat the fungi, later depositing the spores in their droppings. This symbiotic relationship highlights the ingenuity of fungal dispersal strategies.

Finally, some fungi employ explosive mechanisms to disperse spores. The genus *Pilobolus*, commonly known as "hat-thrower fungi," uses internal pressure to launch spore-containing structures several feet into the air, often landing on grazing animals. This method ensures spores are deposited in nutrient-rich environments, such as animal manure, where they can thrive. While less common, these dramatic dispersal methods underscore the adaptability of fungi in propagating themselves.

In practical terms, understanding these dispersal methods can inform strategies for managing fungal growth. For example, in indoor environments, reducing humidity can limit water-based spore dispersal, while regular cleaning can minimize the accumulation of spores on surfaces. By studying these methods, we gain insights into the resilience of fungi and how to coexist with them effectively.

Do Dead Mold Spores Impact Analysis Results? A Detailed Look

You may want to see also

Role of spores in fungal reproduction

Fungi are indeed propagated by spores, a fact that underscores their unique and efficient reproductive strategy. Unlike plants and animals, fungi do not rely on seeds or live offspring for reproduction. Instead, they produce microscopic spores that serve as both dispersal units and survival structures. These spores are lightweight, easily airborne, and capable of withstanding harsh environmental conditions, making them ideal for colonizing new habitats. This method of reproduction allows fungi to thrive in diverse ecosystems, from forest floors to human-made environments.

The role of spores in fungal reproduction is multifaceted. Firstly, spores act as the primary means of dispersal. When released from the fungal structure (such as a mushroom cap or mold colony), they can travel vast distances via wind, water, or even animal vectors. For example, a single mushroom can release billions of spores in a single day, ensuring that at least some will land in favorable conditions for growth. This high-volume strategy increases the likelihood of successful colonization, even in unpredictable environments.

Secondly, spores are remarkably resilient. They can remain dormant for extended periods, sometimes years, until conditions become suitable for germination. This adaptability is crucial for fungi’s survival in fluctuating climates. For instance, in arid regions, spores can lie dormant during dry spells and sprout rapidly after rainfall. Similarly, in colder climates, they can withstand freezing temperatures, only to activate when warmth returns. This ability to "wait out" adverse conditions highlights the spore’s role as a survival mechanism.

Practical applications of fungal spores extend beyond their natural habitats. In agriculture, spores of beneficial fungi like *Trichoderma* are used as biofungicides to control plant diseases. These spores are applied in powdered form, with recommended dosages ranging from 1 to 5 grams per square meter, depending on the crop and severity of infection. Similarly, in food production, spores of *Aspergillus oryzae* are used in fermenting soy sauce and miso, where precise spore counts (typically 10^6 spores/mL) ensure consistent fermentation.

Understanding the role of spores in fungal reproduction also has implications for human health. Fungal spores are a common allergen, affecting approximately 10–20% of the global population. For individuals with allergies or asthma, minimizing exposure to indoor fungal spores is critical. Practical tips include maintaining indoor humidity below 50%, regularly cleaning air conditioning systems, and avoiding carpeting in damp areas. Additionally, HEPA filters can reduce airborne spore counts, providing relief for sensitive individuals.

In conclusion, spores are the cornerstone of fungal reproduction, enabling dispersal, survival, and adaptation. Their versatility has practical applications in agriculture, food production, and health management. By understanding their role, we can harness their benefits while mitigating their drawbacks, showcasing the intricate balance between fungi and their environments.

Does Sterilization Kill Spores? Unraveling the Science Behind Effective Disinfection

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, most fungi are propagated by spores, which are microscopic, single-celled reproductive units.

Fungi produce various types of spores, including asexual spores (e.g., conidia) and sexual spores (e.g., asci, basidiospores, and zygospores), depending on their life cycle.

Fungal spores disperse through air, water, animals, or insects, allowing them to spread to new environments and colonize different substrates.

While most fungi reproduce via spores, some species can also propagate through vegetative methods like fragmentation or mycelial growth.

Spores are crucial for fungal survival as they are highly resilient, enabling fungi to withstand harsh conditions and ensure long-term persistence in diverse ecosystems.