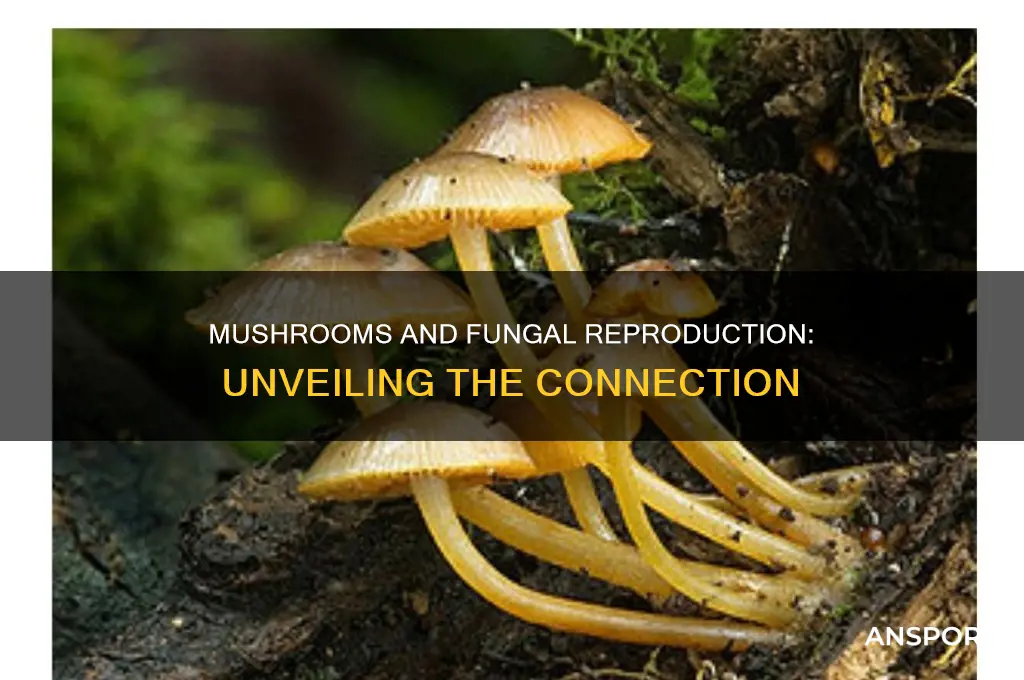

Mushrooms are often associated with the reproductive phase of fungi, but their presence is not solely limited to this stage. While it is true that mushrooms are the visible fruiting bodies produced by certain fungi to disperse spores during reproduction, the fungus itself exists primarily as a network of thread-like structures called mycelium, which grows underground or within organic matter. This mycelium is the vegetative part of the fungus, responsible for nutrient absorption and growth. Mushrooms emerge only under specific environmental conditions, such as adequate moisture and temperature, to facilitate spore production and dispersal. Therefore, while mushrooms are a key indicator of fungal reproduction, they represent just one phase of the fungus's life cycle, and the organism itself persists in other forms throughout its existence.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Mushrooms as Reproductive Structures | Mushrooms are indeed the reproductive structures of certain fungi, specifically basidiomycetes and some ascomycetes. They produce and release spores for reproduction. |

| Presence During Fungal Life Cycle | Mushrooms are only present during the sexual reproductive phase of the fungus. They are not present during the vegetative (growth) phase, which is dominated by the mycelium. |

| Role of Mycelium | The mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus, grows and spreads underground or in its substrate, absorbing nutrients. Mushrooms form when conditions are favorable for reproduction. |

| Spores as Dispersal Units | Mushrooms release spores (e.g., basidiospores or ascospores) that disperse to new locations, where they germinate and grow into new mycelium. |

| Environmental Triggers | Mushroom formation is triggered by specific environmental conditions, such as moisture, temperature, and nutrient availability, which signal the fungus to enter its reproductive phase. |

| Ephemeral Nature | Mushrooms are short-lived structures, typically appearing, releasing spores, and decaying within days to weeks, depending on the species. |

| Non-Reproductive Fungal Forms | Not all fungi produce mushrooms. Some reproduce via asexual spores (e.g., conidia) or other structures like puffballs or truffles, which are also reproductive but differ in form. |

| Ecological Importance | Mushrooms play a crucial role in ecosystem nutrient cycling by dispersing spores and facilitating decomposition and symbiosis with plants (e.g., mycorrhizal fungi). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Fungal Life Cycle Basics: Understanding asexual and sexual reproduction phases in fungi

- Mushroom Formation Process: How mushrooms develop as reproductive structures in fungi

- Non-Reproductive Fungal Forms: Exploring mycelium and other non-mushroom fungal growth stages

- Environmental Triggers for Mushrooms: Factors like moisture and temperature inducing mushroom growth

- Mushrooms vs. Fungal Spores: Differentiating mushrooms as fruiting bodies from spore dispersal mechanisms

Fungal Life Cycle Basics: Understanding asexual and sexual reproduction phases in fungi

Fungi are a diverse group of organisms with a unique life cycle that involves both asexual and sexual reproduction phases. Understanding these phases is crucial to grasping the role of structures like mushrooms in the fungal life cycle. Contrary to the notion that mushrooms are only present during reproduction, they are indeed a visible manifestation of the sexual reproduction phase in certain fungi. However, this is just one part of a complex life cycle that includes various stages and structures. The fungal life cycle begins with the vegetative phase, where the fungus grows and spreads through the production of hyphae, which form a network called the mycelium. This phase is primarily asexual and focuses on nutrient absorption and growth.

Asexual Reproduction in Fungi

Asexual reproduction in fungi is a rapid and efficient method of propagation that does not involve the fusion of gametes. During this phase, fungi produce spores through structures like conidia or sporangiospores. These spores are genetically identical to the parent fungus and are dispersed through air, water, or other means to colonize new environments. Asexual reproduction allows fungi to quickly adapt to favorable conditions and expand their presence. For example, molds often reproduce asexually, producing visible spore structures that can be seen as powdery or fuzzy growths on organic matter. While asexual reproduction is essential for survival and dispersal, it does not involve the formation of mushrooms.

Sexual Reproduction and the Role of Mushrooms

Sexual reproduction in fungi is a more complex process that involves the fusion of haploid cells (gametes) to form a diploid zygote. This phase is critical for genetic diversity and long-term survival. In many fungi, sexual reproduction culminates in the formation of mushrooms, which are the fruiting bodies that produce and disperse sexual spores. Mushrooms are not present during the entire fungal life cycle but are specifically associated with the sexual reproduction phase. They develop from the mycelium when environmental conditions (such as moisture and temperature) are favorable. The gills or pores under the mushroom cap contain the sexual spores, which are released into the environment to initiate new fungal colonies.

The Alternation of Generations

Fungal life cycles often exhibit an alternation of generations, where asexual and sexual phases alternate. In basidiomycetes (the group that includes mushrooms), the life cycle involves a diploid mycelium that undergoes meiosis to produce haploid spores. These spores germinate into haploid mycelia, which can then fuse with compatible partners to form a new diploid mycelium. This cycle ensures genetic recombination and adaptability. Mushrooms are a key part of this sexual phase, serving as the reproductive structures that facilitate spore production and dispersal. Without the sexual phase, fungi would lack the genetic diversity needed to survive changing environments.

Environmental Triggers and Fungal Reproduction

The transition between asexual and sexual phases in fungi is often triggered by environmental factors. For example, nutrient depletion, changes in temperature, or physical disturbances can signal the fungus to shift from vegetative growth to reproductive modes. Mushrooms typically form in response to specific cues, such as increased humidity or the presence of compatible mating partners. This highlights that while mushrooms are not always present, their appearance is a clear indicator of the sexual reproduction phase. Understanding these triggers is essential for studying fungal ecology and managing fungal populations in agriculture, forestry, and medicine.

In conclusion, the fungal life cycle is a dynamic process that includes both asexual and sexual reproduction phases. Mushrooms are a prominent feature of the sexual phase, serving as the structures that produce and disperse sexual spores. However, they are not the only reproductive strategy employed by fungi. Asexual reproduction, through spores like conidia, plays a vital role in growth and dispersal. By understanding these phases, we gain insight into the adaptability and resilience of fungi, which are among the most successful organisms on Earth.

Boosting Immunity: The Science Behind Mushroom Supplements' Health Benefits

You may want to see also

Mushroom Formation Process: How mushrooms develop as reproductive structures in fungi

Mushrooms are indeed reproductive structures of fungi, specifically the fruiting bodies that produce and disperse spores. The formation of mushrooms is a complex process that occurs under specific environmental conditions, primarily when the fungus is ready to reproduce. This process begins with the vegetative growth phase of the fungus, where the mycelium—a network of thread-like structures called hyphae—expands through the substrate, absorbing nutrients. During this phase, the fungus is focused on growth and survival rather than reproduction. However, when conditions such as adequate moisture, temperature, and nutrient availability are met, the fungus transitions to its reproductive phase, initiating the development of mushrooms.

The first stage of mushroom formation involves the aggregation of hyphae into a structure called a primordium. This small, knot-like mass forms beneath the substrate surface and serves as the foundation for the mushroom. The primordium develops through cellular differentiation, where specific hyphae take on specialized roles in forming the mushroom’s cap, stem, and gills. This process is highly regulated by genetic and environmental factors, ensuring the proper development of the fruiting body. As the primordium grows, it pushes through the substrate, becoming visible as a tiny pinhead-like structure, often referred to as "pinning."

Once the primordium emerges, it enters the rapid growth phase, where the mushroom expands in size and develops its characteristic features. The cap (pileus) and stem (stipe) elongate, while the underside of the cap forms gills (in agarics) or pores (in boletes), which house the spore-producing cells. These structures are crucial for reproduction, as they contain basidia—club-shaped cells that produce spores through meiosis. The gills or pores maximize the surface area for spore production, ensuring efficient dispersal when mature. This growth phase is highly sensitive to environmental conditions, such as humidity and light, which can influence the mushroom’s final size and shape.

The final stage of mushroom formation is spore maturation and release. As the basidia mature, they undergo karyogamy (fusion of nuclei) and meiosis to produce haploid spores. These spores are then released into the environment, often through passive mechanisms like wind or water. The timing of spore release is critical, as it must coincide with favorable conditions for spore germination and mycelium establishment. Once spores are dispersed, the mushroom’s role in the reproductive cycle is complete, and it begins to senesce, decomposing and returning nutrients to the substrate.

It is important to note that mushrooms are not always present in the fungal life cycle. They appear only during the reproductive phase, triggered by specific environmental cues. This distinguishes them from the vegetative mycelium, which persists throughout the fungus’s life, focusing on nutrient absorption and growth. Thus, mushrooms are ephemeral structures, serving the sole purpose of sexual reproduction and ensuring the survival and dispersal of the fungal species. Understanding this process highlights the intricate relationship between fungi and their environment, as well as the adaptive strategies they employ for reproduction.

Colorado's Mushroom Legalization: What's the Deal?

You may want to see also

Non-Reproductive Fungal Forms: Exploring mycelium and other non-mushroom fungal growth stages

Fungi are incredibly diverse organisms with complex life cycles that extend far beyond the visible mushrooms we often associate with them. While mushrooms are indeed reproductive structures, they represent only a small fraction of a fungus's life cycle. The majority of a fungus's existence is spent in non-reproductive forms, primarily as mycelium, a network of thread-like structures called hyphae. Mycelium is the vegetative part of the fungus, responsible for nutrient absorption, growth, and colonization of substrates. This network can spread extensively through soil, wood, or other organic matter, often remaining hidden from view. Understanding mycelium and other non-mushroom forms is crucial for appreciating the full scope of fungal biology and their ecological roles.

Mycelium is the workhorse of the fungal world, performing essential functions such as decomposition, nutrient cycling, and symbiotic relationships with plants. Unlike mushrooms, which are ephemeral and appear only under specific conditions, mycelium persists year-round, adapting to environmental changes. Hyphae, the individual filaments of mycelium, secrete enzymes to break down complex organic materials, releasing nutrients that the fungus absorbs. This process is vital for ecosystem health, as fungi are primary decomposers in many environments. Additionally, mycelium forms mutualistic relationships with plant roots, known as mycorrhizae, which enhance nutrient uptake for both the fungus and the plant. These non-reproductive forms highlight the fungus's role as a keystone organism in ecosystems.

Beyond mycelium, fungi exhibit other non-reproductive structures that are equally important. For instance, some fungi produce spores directly from hyphae without forming mushrooms, a process known as asexual reproduction. These spores, such as conidia, are dispersed through air or water to colonize new habitats. Another example is the formation of sclerotia, hardened masses of mycelium that serve as survival structures in adverse conditions. Sclerotia can remain dormant for years, only sprouting when environmental conditions improve. These structures demonstrate the fungus's adaptability and resilience, allowing it to thrive in diverse and challenging environments.

Exploring non-reproductive fungal forms also reveals their potential applications in biotechnology and industry. Mycelium, for example, is being used as a sustainable material for packaging, textiles, and even building materials due to its strength and biodegradability. Additionally, fungi's ability to produce enzymes and secondary metabolites in their vegetative state has led to advancements in medicine, agriculture, and bioremediation. By focusing on these non-mushroom stages, researchers can unlock new possibilities for harnessing fungal capabilities.

In conclusion, mushrooms are just the tip of the fungal iceberg, representing a brief reproductive phase in a much longer and more complex life cycle. Non-reproductive forms, such as mycelium, sclerotia, and asexual spores, are the foundation of fungal existence, driving ecosystem processes and offering innovative solutions to human challenges. By studying these often-overlooked stages, we gain a deeper understanding of fungi's ecological significance and their potential contributions to science and industry. Fungi's non-reproductive forms are a testament to their versatility and importance in the natural world.

Butter Mushroom Delight: Calories Unveiled

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Triggers for Mushrooms: Factors like moisture and temperature inducing mushroom growth

Mushrooms, the visible fruiting bodies of certain fungi, are not always present during the fungus's life cycle. They typically appear under specific environmental conditions that trigger their growth. Among the most critical factors are moisture and temperature, which play pivotal roles in inducing mushroom formation. Fungi, being heterotrophic organisms, rely on external resources for energy and nutrients, and their reproductive structures—mushrooms—emerge when conditions are optimal for spore dispersal. Understanding these environmental triggers is essential for both mycologists and enthusiasts seeking to cultivate or study mushrooms in their natural habitats.

Moisture is arguably the most critical environmental factor influencing mushroom growth. Fungi require water for cellular processes, nutrient absorption, and spore development. In nature, mushrooms often appear after rainfall or in humid environments because water activates dormant fungal mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus. The mycelium absorbs moisture, triggering metabolic processes that lead to the formation of mushrooms. However, excessive moisture can be detrimental, as it may cause waterlogging or promote the growth of competing organisms. Optimal moisture levels vary among species, but most mushrooms thrive in environments with consistent, moderate humidity. For cultivation, maintaining proper substrate moisture through misting or humidifiers is crucial to induce and sustain mushroom growth.

Temperature is another key factor that dictates whether mushrooms will form. Different fungal species have specific temperature ranges within which they can reproduce. For example, some mushrooms, like oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), grow well in cooler temperatures (15–25°C), while others, such as shiitake mushrooms (*Lentinula edodes*), prefer warmer conditions (20–30°C). Temperature influences enzymatic activity within the mycelium, affecting nutrient breakdown and energy allocation for mushroom development. In nature, seasonal temperature changes often correlate with mushroom fruiting, such as the appearance of chanterelles in late summer or morels in spring. For cultivators, controlling temperature through environmental regulation or incubation is essential to mimic these natural triggers and encourage mushroom production.

The interplay between moisture and temperature creates a delicate balance that determines whether mushrooms will emerge. For instance, a sudden increase in moisture combined with suitable temperatures can rapidly induce fruiting. Conversely, prolonged dry or cold conditions may suppress mushroom formation, as the fungus conserves energy in its mycelial form. In ecosystems, this dynamic ensures that mushrooms appear when conditions maximize spore dispersal, such as after rain in temperate forests. Cultivators often replicate these natural cycles by adjusting humidity and temperature in controlled environments, such as grow rooms or greenhouses, to optimize mushroom yields.

Beyond moisture and temperature, other environmental factors like light, pH, and substrate composition also influence mushroom growth, though their impact is often secondary. For example, while most fungi do not require light for energy, some species use light as a signal to initiate fruiting. Similarly, the pH of the substrate affects nutrient availability, which in turn impacts mycelial health and mushroom formation. However, moisture and temperature remain the primary triggers, as they directly control the physiological processes that lead to mushroom development. By manipulating these factors, both in nature and in cultivation, one can predict and enhance mushroom growth, highlighting their central role in the fungal life cycle.

Mushrooms: Carnivorous or Not?

You may want to see also

Mushrooms vs. Fungal Spores: Differentiating mushrooms as fruiting bodies from spore dispersal mechanisms

Mushrooms and fungal spores are both integral components of the fungal life cycle, yet they serve distinct roles and represent different stages of fungal development. Mushrooms, often recognized by their umbrella-like caps and stems, are the visible fruiting bodies of certain fungi. These structures are not always present in the fungal life cycle but emerge specifically during the reproductive phase. In contrast, fungal spores are microscopic, seed-like structures produced by fungi for the purpose of dispersal and propagation. Understanding the difference between mushrooms and fungal spores is crucial for grasping how fungi reproduce and spread.

Mushrooms function as the reproductive organs of fungi, akin to the flowers of plants. They are formed when environmental conditions—such as adequate moisture, temperature, and nutrient availability—signal the fungus to enter its reproductive stage. The primary purpose of a mushroom is to produce and disperse spores. Inside the mushroom’s gills, pores, or teeth, spores are generated in vast quantities. Once mature, these spores are released into the environment, where they can travel via air, water, or animals to colonize new habitats. Thus, mushrooms are ephemeral structures that appear only when the fungus is actively reproducing.

Fungal spores, on the other hand, are the means by which fungi propagate and survive. They are incredibly resilient, capable of withstanding harsh conditions such as drought, extreme temperatures, and lack of nutrients. Spores remain dormant until they land in a suitable environment, where they germinate and grow into new fungal organisms. Unlike mushrooms, spores are not limited to the reproductive phase; they can be produced by various parts of the fungus, including molds and other non-mushroom structures. This distinction highlights that while mushrooms are tied to reproduction, spores are a more versatile and persistent mechanism for fungal survival and dispersal.

The relationship between mushrooms and spores underscores the complexity of fungal reproduction. Mushrooms are the visible manifestation of a fungus’s reproductive efforts, but they are not the only way fungi produce spores. For example, some fungi release spores directly from molds or other structures without forming mushrooms. This diversity in spore production strategies reflects the adaptability of fungi to different environments. Therefore, while mushrooms are a prominent indicator of fungal reproduction, they are not the sole mechanism by which fungi disperse their spores.

In summary, mushrooms and fungal spores play complementary yet distinct roles in the fungal life cycle. Mushrooms are the fruiting bodies that emerge during the reproductive phase to facilitate spore production and dispersal. Spores, however, are the actual units of propagation, capable of surviving and spreading independently of mushrooms. Recognizing this difference clarifies that mushrooms are not always present in the fungal life cycle but are specifically associated with reproduction. Meanwhile, spores are a constant feature of fungal biology, ensuring the longevity and dispersal of these organisms across diverse ecosystems.

Swedish Meatballs: Do Mushrooms Make the Dish?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of fungi and are produced specifically during the reproductive phase to release spores.

Yes, many fungi spend most of their life cycle in a vegetative state (as mycelium) and only produce mushrooms under specific conditions for reproduction.

No, not all fungi produce mushrooms. Some fungi reproduce via spores released from other structures, such as molds or yeasts.

Mushroom production is typically triggered by environmental factors like temperature, humidity, and nutrient availability, which signal optimal conditions for spore dispersal.

No, fungi can reproduce asexually through fragmentation or spore production, but mushrooms are a common reproductive structure for many species.