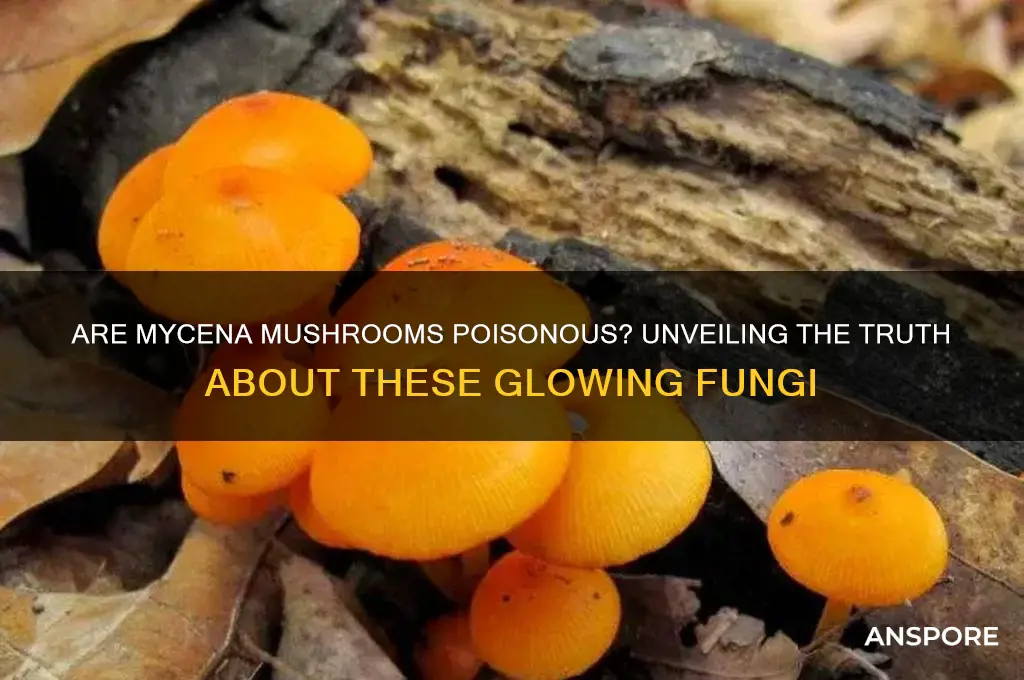

Mycena mushrooms, commonly known as bonnet mushrooms, are a diverse genus of fungi characterized by their small, delicate fruiting bodies and often vibrant colors. While many species of Mycena are not considered highly toxic, their edibility varies widely, and some can cause mild gastrointestinal discomfort if consumed. It is crucial to note that a few species, such as *Mycena pura* (the lilac bonnet), are generally regarded as edible in small quantities, but accurate identification is essential due to the presence of potentially harmful look-alikes. As a general rule, foraging for Mycena mushrooms without expert guidance is discouraged, as misidentification can lead to poisoning. Always consult a reliable field guide or a mycologist before consuming any wild mushrooms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Edibility | Most Mycena species are considered inedible or potentially toxic. Some species may cause gastrointestinal upset if consumed. |

| Toxicity Level | Generally mildly toxic to non-toxic, but not recommended for consumption due to lack of culinary value and potential risks. |

| Common Species | Mycena pura (known as "Fairy Helmet") is one of the few species occasionally consumed, but even this is not widely recommended. |

| Symptoms of Poisoning | Mild gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) if ingested. No severe or life-threatening effects reported. |

| Active Compounds | Unknown specific toxins, but some species may contain irritants or mild toxins. |

| Identification Difficulty | High. Many Mycena species are small, delicate, and easily confused with other mushrooms, increasing the risk of misidentification. |

| Culinary Use | Not used in cooking due to lack of flavor, small size, and potential toxicity. |

| Habitat | Found in forests, often on decaying wood or leaf litter, worldwide. |

| Conservation Status | Not typically threatened, but habitat loss can impact populations. |

| Recommendation | Avoid consumption. Appreciate Mycena mushrooms for their aesthetic value rather than as a food source. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Common Mycena Species Toxicity

Mycena mushrooms, often referred to as "bonnet mushrooms," are a diverse genus with over 500 species, many of which are known for their delicate, colorful fruiting bodies. While the majority of Mycena species are not considered deadly, their toxicity levels vary widely, making identification crucial for foragers. For instance, *Mycena pura*, commonly known as the Lilac Bonnet, is generally regarded as edible but lacks substantial flavor, leading many to avoid it. In contrast, *Mycena leucophaea*, or the White Edge Bonnet, contains compounds that can cause gastrointestinal distress in some individuals, though severe reactions are rare.

When assessing toxicity, it’s essential to consider both the species and the individual’s sensitivity. For example, *Mycena rosea*, the Rosy Mycena, is often consumed in small quantities without adverse effects, but its safety is not universally agreed upon. Some foragers report mild stomach upset after ingestion, suggesting that tolerance varies. As a rule of thumb, consuming any wild mushroom in large quantities, even those considered edible, can lead to discomfort. For beginners, it’s advisable to start with a small sample (e.g., one or two caps) and wait 24 hours to monitor for reactions before consuming more.

One of the most debated species is *Mycena chlorophos*, the bioluminescent mushroom known for its striking green glow. While it is not known to be fatally toxic, its edibility remains uncertain. Some sources suggest it may cause mild hallucinations or nausea, though these claims lack scientific consensus. Given its rarity and ecological significance, foragers are generally discouraged from consuming it. Instead, appreciating its beauty in the wild is the recommended approach, aligning with ethical foraging practices.

For those interested in identifying Mycena species, a few key characteristics can help mitigate risk. Always examine the mushroom’s gill attachment, spore color, and habitat. For instance, *Mycena galopus*, or the Milky Mycena, exudes a milky latex when damaged, a feature that distinguishes it from similar species. However, even with proper identification, cross-contamination with nearby toxic fungi is a risk. Always clean mushrooms thoroughly and cook them before consumption, as heat can break down potential toxins.

In conclusion, while many Mycena species are not fatally poisonous, their edibility is often uncertain and highly dependent on individual tolerance. Foragers should prioritize caution, relying on expert guides or mycological resources for accurate identification. When in doubt, the safest approach is to admire these mushrooms in their natural habitat rather than risk ingestion. After all, the beauty of Mycenas lies not in their culinary value but in their ecological role and aesthetic appeal.

Are Paleonia's Brown Mushrooms Poisonous? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Symptoms of Mycena Poisoning

Mycena mushrooms, often recognized by their delicate, bioluminescent caps, are generally considered non-toxic. However, not all species within the Mycena genus are safe for consumption. Misidentification can lead to ingestion of toxic varieties, triggering a range of symptoms that vary in severity. Understanding these symptoms is crucial for anyone foraging or accidentally consuming these mushrooms.

The onset of symptoms typically occurs within 30 minutes to 2 hours after ingestion, depending on the species and quantity consumed. Gastrointestinal distress is the most common reaction, manifesting as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. These symptoms are often accompanied by dehydration, which can be particularly dangerous for children, the elderly, or individuals with compromised immune systems. In rare cases, ingestion of toxic Mycena species may lead to more severe reactions, such as dizziness, confusion, or mild hallucinations, though these are less documented and depend on the specific toxin involved.

Analyzing Severity and Risk Factors

While most Mycena poisonings are mild and resolve within 24 hours, certain factors can exacerbate symptoms. For instance, consuming large quantities or combining mushrooms with alcohol can intensify the body’s reaction. Additionally, individuals with pre-existing liver or kidney conditions may experience prolonged or more severe symptoms. It’s essential to monitor for signs of dehydration, especially in children, as this can complicate recovery. If symptoms persist or worsen, immediate medical attention is advised.

Practical Tips for Prevention and Response

To avoid Mycena poisoning, always consult a field guide or expert before consuming wild mushrooms. Avoid foraging in areas contaminated by pollutants, as some Mycena species can accumulate toxins from their environment. If poisoning is suspected, induce vomiting only if advised by a poison control center or healthcare professional. Instead, focus on rehydration and rest while seeking medical advice. Keep a sample of the mushroom for identification, as this can aid in treatment.

Comparative Perspective

Compared to more notorious toxic mushrooms like Amanita species, Mycena poisoning is generally less severe. However, the lack of widespread awareness about toxic Mycena varieties makes them a hidden risk. While Amanita poisoning often involves liver or kidney damage, Mycena toxicity tends to be more localized to the gastrointestinal system. This distinction highlights the importance of species-specific knowledge in mushroom safety.

Takeaway

While most Mycena mushrooms are harmless, the potential for misidentification and toxicity exists. Recognizing symptoms such as gastrointestinal distress, dehydration, and mild neurological effects is key to prompt and effective response. Prevention through proper identification and cautious foraging remains the best defense against Mycena poisoning. When in doubt, err on the side of caution and avoid consumption altogether.

Are Dead Man's Fingers Mushrooms Poisonous? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Edible vs. Poisonous Varieties

Mycena mushrooms, often lumped into the "little brown mushrooms" category, present a fascinating yet perilous dichotomy. While some species are edible and even prized for their delicate flavor, others harbor toxins that can cause severe gastrointestinal distress or worse. This duality demands careful identification, as missteps can have dire consequences. For instance, *Mycena pura*, commonly known as the lilac bonnet, is considered edible and is appreciated in culinary circles for its mild, earthy taste. Conversely, *Mycena leucopallens* contains toxins that can lead to nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea if ingested. The challenge lies in their morphological similarities, making field identification unreliable without expert knowledge or laboratory analysis.

To navigate this complexity, foragers must adopt a meticulous approach. Start by examining spore color, a critical diagnostic feature. Edible species like *Mycena haematopus* (the bleeding fairy helmet) have white spores, while some toxic varieties may exhibit different colors. Habitat is another clue: edible Mycenas often grow on wood, while poisonous ones may prefer soil. However, these rules are not absolute. A more foolproof method involves consulting a mycologist or using a field guide with detailed descriptions and photographs. For beginners, the safest rule is to avoid consuming any Mycena mushroom unless its edibility is confirmed by an expert.

The risks of misidentification are not to be underestimated. Even small quantities of toxic Mycenas can cause symptoms within hours of ingestion. Children and pets are particularly vulnerable due to their lower body mass, making it essential to keep foraged mushrooms out of their reach. If accidental ingestion occurs, immediate medical attention is crucial. Symptoms like abdominal pain, dizziness, or hallucinations warrant a call to poison control or a visit to the emergency room. Carrying a portable mushroom identification guide or using a smartphone app can provide quick reference in the field, though these tools should supplement, not replace, expert advice.

Despite the dangers, the allure of edible Mycenas persists, especially among experienced foragers. Their delicate texture and subtle flavor make them a rewarding find for those who can identify them safely. One practical tip is to focus on a few well-documented edible species and learn their unique characteristics thoroughly. For example, *Mycena epipterygia* (the orange mycena) is both edible and distinctive, with its bright orange cap and bioluminescent properties. By narrowing the scope and practicing caution, foragers can enjoy the benefits of these mushrooms while minimizing risks.

In conclusion, the edible vs. poisonous debate in Mycenas underscores the broader principle of mushroom foraging: when in doubt, leave it out. The thin line between a culinary delight and a toxic hazard demands respect for the complexity of fungal identification. While some Mycenas offer gastronomic rewards, the potential consequences of a mistake far outweigh the benefits of a risky meal. Armed with knowledge, caution, and humility, foragers can appreciate the beauty of these mushrooms without endangering themselves or others.

Glow-in-the-Dark Mushrooms: Are They Poisonous or Safe to Touch?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Safe Handling and Identification

Mycena mushrooms, often lumped into the "little brown mushrooms" category, present a challenge for foragers due to their sheer diversity. Over 500 species exist, and while many are considered inedible due to their unpalatable taste or insignificant size, a handful are reportedly edible. However, pinpointing these edible species requires meticulous identification, as several Mycena species contain toxins that can cause gastrointestinal distress.

Understanding the potential risks associated with misidentification is crucial. Consuming even a small amount of a toxic Mycena species can lead to unpleasant symptoms like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. This highlights the importance of approaching these mushrooms with caution and prioritizing accurate identification before considering consumption.

Visual Clues and Field Identification:

The first line of defense against accidental poisoning is accurate field identification. Mycena mushrooms typically have a distinctive appearance: small, delicate caps often with a conical or bell-shaped profile, and slender, fragile stems. Their colors range from white and gray to various shades of brown, sometimes with a slight bluish or greenish tint. Look for key features like the presence of a partial veil (a thin membrane connecting the cap to the stem in young mushrooms), the color and texture of the gills, and the overall habitat where the mushroom is found. For example, some Mycena species prefer decaying wood, while others are found in grassy areas.

Utilizing field guides, reputable online resources, and consulting with experienced mycologists are essential tools for accurate identification. Remember, relying solely on color or general appearance can be misleading, as several Mycena species share similar characteristics.

Handling and Preparation (If Identified as Edible):

Even if you've confidently identified an edible Mycena species, proper handling is crucial. Always wear gloves when handling wild mushrooms to avoid skin irritation from potential toxins or allergens. Thoroughly clean the mushrooms by gently brushing off dirt and debris. Avoid washing them, as they absorb water readily, which can dilute their flavor and potentially concentrate any remaining toxins.

Some foragers recommend blanching edible Mycena species in boiling water for a brief period before cooking to further reduce the risk of any potential toxins. However, this step is not universally accepted, and its effectiveness varies depending on the specific species.

A Word of Caution:

While some Mycena species are considered edible, the risks associated with misidentification are significant. The consequences of consuming a toxic species can be severe, especially for children, the elderly, or individuals with compromised immune systems. If you are unsure about the identification of a Mycena mushroom, err on the side of caution and do not consume it. Consulting with a local mycological society or a certified mushroom expert is always the safest course of action. Remember, accurate identification is paramount when dealing with wild mushrooms, and when in doubt, leave it out.

Are Conocybe Mushrooms Poisonous? A Comprehensive Guide to Their Toxicity

You may want to see also

Historical Poisoning Cases

Mycena mushrooms, often lumped into the broader category of "mycena," encompass a diverse genus with over 500 species. While many are considered non-toxic, historical records and case studies reveal instances where consumption led to adverse effects. One notable example involves *Mycena pura*, commonly known as the lilac bonnet. In 1987, a family in Oregon experienced mild gastrointestinal distress after mistaking this species for edible *Laccaria* mushrooms. Though not fatal, the incident underscores the importance of precise identification, as even seemingly benign mycena species can cause discomfort when ingested in quantities exceeding 100 grams.

A more severe case dates back to 1892 in Germany, where a group of foragers consumed *Mycena inclinata*, or the clustered bonnet. Three individuals, aged 25 to 40, reported symptoms including nausea, dizziness, and temporary vision impairment within two hours of ingestion. Analysis later revealed the presence of trace amounts of muscarine, a compound found in some mycena species. While muscarine is generally not lethal in small doses, its cholinergic effects can be dangerous for individuals with pre-existing heart or respiratory conditions. This case highlights the need for caution, especially when consuming wild mushrooms without expert verification.

In contrast, *Mycena galopus*, or the milky mycena, has been implicated in a 1954 poisoning in Sweden. A 12-year-old child ingested a small cap (approximately 5 grams) and experienced profuse sweating, confusion, and a rapid heartbeat. The symptoms subsided within 24 hours, but the incident sparked debate among mycologists about the potential toxicity of this species. While some argue that the child’s reaction was due to individual sensitivity, others suggest that *M. galopus* may contain unidentified compounds that warrant further study. This case serves as a reminder that even small doses of certain mycena species can pose risks, particularly to children and vulnerable populations.

To avoid historical pitfalls, foragers should adhere to strict guidelines. Always consult a field guide or expert before consuming any wild mushroom. Pay attention to subtle differences in color, gill structure, and habitat, as these can distinguish toxic species from their edible counterparts. If in doubt, discard the mushroom entirely. In the event of accidental ingestion, monitor for symptoms such as sweating, blurred vision, or abdominal pain, and seek medical attention immediately. While mycena mushrooms are not universally poisonous, their historical involvement in poisoning cases demands respect and caution.

Are Mushrooms Safe for Guinea Pigs? A Poison Risk Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all Mycena mushrooms are poisonous. While some species, like *Mycena pura* (Lilac Bonnet), are edible and considered safe, others may cause gastrointestinal upset or be toxic. Always identify the specific species before consuming.

Most Mycena species are not known to cause severe poisoning, but some may lead to mild symptoms like stomachache or nausea if ingested. There are no reports of fatal poisonings from Mycena mushrooms.

It’s difficult to determine edibility without proper identification. Consult a reliable field guide or expert, as some Mycena species resemble toxic mushrooms. Avoid consuming any Mycena unless you are absolutely certain of its identity.