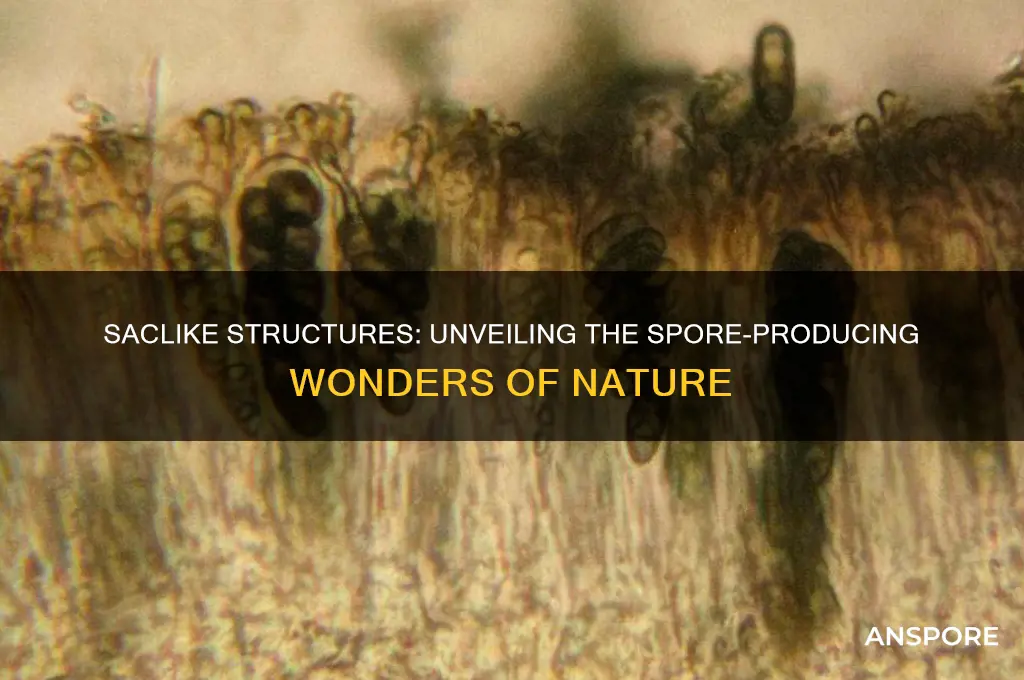

Saclike structures that produce many spores, known as sporangia, are essential components in the life cycles of various organisms, particularly fungi and certain plants. These specialized structures serve as the primary sites for spore formation, enabling the dispersal and propagation of the species. In fungi, sporangia are often found at the tips of hyphae or within fruiting bodies, where they undergo meiosis to produce haploid spores. Similarly, in plants like ferns and mosses, sporangia develop on the undersides of leaves or specialized structures, releasing spores that can grow into new individuals under favorable conditions. This reproductive strategy ensures genetic diversity and enhances survival in diverse environments, making sporangia a fascinating and critical aspect of biology.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Zygosporangia: Thick-walled, resistant structures formed by zygomycetes, containing multiple spores for survival

- Sporangia: Saclike structures in fungi and plants, releasing spores for reproduction and dispersal

- Ascomata: Flask-shaped structures in ascomycetes, producing ascospores for sexual reproduction

- Basidiocarps: Fruiting bodies of basidiomycetes, housing basidia that generate basidiospores

- Conidiomata: Structures in fungi producing conidia, asexual spores for rapid propagation

Zygosporangia: Thick-walled, resistant structures formed by zygomycetes, containing multiple spores for survival

Zygosporangia stand out as nature’s survival capsules in the fungal kingdom, engineered by zygomycetes to endure harsh conditions. These thick-walled structures are not merely protective shells but sophisticated repositories housing multiple spores. Unlike fragile sporangia that release spores immediately, zygosporangia are built to last, often surviving extreme temperatures, desiccation, and nutrient scarcity. This resilience ensures the long-term preservation of genetic material, allowing zygomycetes to persist in environments where other fungi might perish.

To understand their function, consider zygosporangia as fungal seed banks. Formed during sexual reproduction, they result from the fusion of gametangia, creating a zygote that develops into the zygosporangium. This process is triggered under stress, such as nutrient depletion, signaling the fungus to invest in survival rather than immediate propagation. The thick walls, composed of chitin and other polymers, act as a barrier against environmental stressors, while the dormant spores inside await favorable conditions to germinate.

Practical observation of zygosporangia requires a microscope, as they are typically microscopic in size. For enthusiasts or students, collecting soil samples from decaying organic matter—a favored habitat of zygomycetes—increases the likelihood of finding these structures. Staining techniques, such as using cotton blue or lactophenol cotton blue, enhance visibility, revealing their spherical or oval shapes and robust walls. This hands-on approach not only aids identification but also underscores the adaptability of zygomycetes in diverse ecosystems.

From an ecological perspective, zygosporangia play a critical role in soil health and nutrient cycling. By surviving adverse conditions, they ensure the continuity of zygomycete populations, which are essential decomposers in many habitats. Their ability to remain dormant for years highlights the fungal kingdom’s evolutionary ingenuity, offering lessons in resilience that could inspire biotechnology or conservation strategies. Understanding zygosporangia is not just academic—it’s a window into the mechanisms that sustain life in challenging environments.

For those cultivating fungi or studying microbial ecology, recognizing zygosporangia can indicate environmental stress or shifts in fungal communities. While they are not directly harmful, their presence may signal conditions unfavorable for active fungal growth. Conversely, their absence in typical zygomycete habitats could suggest disturbances in the ecosystem. By monitoring these structures, researchers and hobbyists alike can gain insights into fungal responses to environmental changes, making zygosporangia both a marker and a marvel of microbial survival.

Unveiling the Truth: Does Moss Have Spores and How Do They Spread?

You may want to see also

Sporangia: Saclike structures in fungi and plants, releasing spores for reproduction and dispersal

Sporangia, the saclike structures found in fungi and plants, serve as the factories for spore production, playing a critical role in reproduction and dispersal. These structures are not merely passive containers; they are dynamic, often undergoing complex developmental processes to ensure the successful release of spores. In ferns, for example, sporangia cluster into structures called sori, typically found on the undersides of leaves. Each sporangium can produce hundreds to thousands of spores, depending on the species, ensuring a high probability of successful colonization in new environments.

Consider the lifecycle of a fungus like *Physarum polycephalum*, a slime mold that relies on sporangia for survival. When environmental conditions deteriorate, the fungus aggregates into a sporangium, a protective sac that shelters the spores until conditions improve. This process is a survival mechanism, showcasing how sporangia act as both reproductive and protective structures. For gardeners or mycologists, understanding this lifecycle can inform strategies for cultivating or controlling fungal growth, such as adjusting humidity levels to discourage sporangium formation in unwanted areas.

From a comparative perspective, sporangia in plants and fungi differ in structure and function despite their shared purpose. In plants like mosses and ferns, sporangia are typically multicellular and attached to the parent plant, releasing spores through a slit or pore. In contrast, fungal sporangia are often unicellular or composed of a few cells, and they may detach entirely to disperse spores via wind or water. This distinction highlights the evolutionary adaptations of these organisms to their respective environments, with plant sporangia optimized for stability and fungal sporangia for mobility.

For practical application, identifying sporangia can aid in plant and fungal classification. In ferns, the position and shape of sori (clusters of sporangia) are key diagnostic features. For instance, the maidenhair fern (*Adiantum*) has sori along the leaf margins, while the ostrich fern (*Matteuccia struthiopteris*) has them beneath the leaf pinnae. In fungi, sporangia often appear as powdery masses or mold-like growths, such as those seen in bread mold (*Rhizopus stolonifer*). Recognizing these structures can help in early detection of fungal infestations in crops or stored food, allowing for timely intervention.

Finally, the study of sporangia offers insights into evolutionary biology and biotechnology. Researchers are exploring how sporangia develop and function at the molecular level, uncovering genes and pathways that could be targeted for crop improvement or antifungal treatments. For instance, manipulating sporangium formation in fungi could lead to new strategies for controlling plant diseases. Similarly, understanding how plant sporangia respond to environmental cues could enhance breeding programs for stress-tolerant crops. Whether in the lab or the field, sporangia remain a fascinating and practical area of study with broad implications for science and industry.

Are Resting Spores Infectious? Unveiling Their Role in Disease Transmission

You may want to see also

Ascomata: Flask-shaped structures in ascomycetes, producing ascospores for sexual reproduction

Ascomata, the flask-shaped structures found in ascomycetes, are marvels of fungal anatomy, serving as the primary sites for sexual reproduction in this diverse group of organisms. These sac-like formations are not merely passive containers; they are dynamic microenvironments where the intricate process of ascospore production unfolds. Within the ascoma, asci—the spore-bearing cells—develop, each containing typically eight ascospores. This efficient design ensures the prolific dissemination of genetic material, a critical factor in the survival and adaptation of ascomycetes across varied ecosystems.

Consider the lifecycle of *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, a well-studied ascomycete. During sexual reproduction, two haploid cells fuse to form a diploid zygote, which then undergoes meiosis within the ascoma. The resulting asci are encased in a protective layer, shielding the developing ascospores from environmental stressors. Once mature, the ascoma ruptures, releasing the ascospores into the environment. This process is not just a biological curiosity; it has practical implications, particularly in industries like fermentation, where understanding ascospore production can optimize yeast performance.

From a comparative perspective, ascomata stand in stark contrast to structures like sporangia in other fungi, which are often simpler and lack the complexity of ascocarp development. The flask-like shape of ascomata is not arbitrary; it maximizes surface area for ascospore release while minimizing exposure to predators or adverse conditions. This evolutionary adaptation highlights the sophistication of ascomycetes in ensuring reproductive success. For instance, in truffles (*Tuber* spp.), the ascomata are subterranean, relying on animals for spore dispersal, a strategy that underscores the diversity of ascomata functions.

For those studying or working with ascomycetes, observing ascomata under a microscope can provide valuable insights. A 40x to 100x magnification is ideal for visualizing the asci and ascospores within the ascoma. Staining techniques, such as using lactophenol cotton blue, can enhance contrast and reveal structural details. Additionally, maintaining a humid environment during sample preparation is crucial, as desiccation can distort the ascoma’s delicate architecture. These practical tips ensure accurate analysis and appreciation of these remarkable structures.

In conclusion, ascomata are not just sac-like structures but intricate reproductive organs that exemplify the ingenuity of fungal biology. Their role in producing ascospores for sexual reproduction is pivotal, driving genetic diversity and adaptability in ascomycetes. Whether in scientific research, industrial applications, or ecological studies, understanding ascomata offers a window into the fascinating world of fungi, blending biological elegance with practical utility.

Stun Spore vs. Electric Types: Does It Work in Pokémon Battles?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Basidiocarps: Fruiting bodies of basidiomycetes, housing basidia that generate basidiospores

In the intricate world of fungi, basidiocarps stand as marvels of nature, serving as the reproductive powerhouses of basidiomycetes. These sac-like structures, often visible as mushrooms or toadstools, are not merely the fruiting bodies we see above ground but complex organs housing basidia—the spore-producing factories. Each basidium generates multiple basidiospores, ensuring the widespread dissemination of fungal genetics. This process is a testament to the efficiency and adaptability of basidiomycetes, which include some of the most ecologically and economically significant fungi, such as shiitake, portobello, and the deadly amanita.

To understand basidiocarps, consider their structure and function. The exterior, often colorful and varied in texture, protects the internal spore-bearing tissue. Beneath this lies the hymenium, a layer rich in basidia. Each basidium typically produces four spores, which are launched into the environment via a sophisticated mechanism involving a drop of fluid and surface tension. For enthusiasts or mycologists studying these structures, observing the hymenium under a microscope reveals the intricate dance of spore production. Practical tip: When collecting samples, ensure the basidiocarp is mature, as immature specimens may not yet have developed spores.

From a comparative perspective, basidiocarps differ significantly from the asci of ascomycetes, another major fungal group. While asci release spores explosively, basidia rely on a more gradual, passive mechanism. This distinction highlights the evolutionary divergence in spore dispersal strategies. For instance, the fly agaric (*Amanita muscaria*) uses its vibrant red cap to attract animals, which inadvertently spread its spores. In contrast, bracket fungi like *Ganoderma* produce spores in large quantities, relying on wind dispersal. Understanding these differences is crucial for identifying fungi in the wild or cultivating them for food, medicine, or research.

For those interested in cultivating basidiomycetes, creating optimal conditions for basidiocarp formation is key. Factors such as humidity (ideally 85–95%), temperature (20–25°C for most species), and substrate composition play critical roles. For example, shiitake mushrooms (*Lentinula edodes*) thrive on hardwood logs, while oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) prefer straw. Caution: Avoid overwatering, as excessive moisture can lead to bacterial contamination. Additionally, patience is essential; basidiocarp development can take weeks to months, depending on the species.

In conclusion, basidiocarps are not just sac-like structures but sophisticated biological systems that ensure the survival and propagation of basidiomycetes. Their diversity in form and function reflects the adaptability of fungi to various ecosystems. Whether you’re a forager, cultivator, or researcher, understanding basidiocarps opens doors to appreciating the hidden world of fungi and harnessing their potential in food, medicine, and ecology. Practical takeaway: Always identify wild basidiocarps accurately, as some species are toxic or hallucinogenic, while others are culinary treasures.

Detecting Mold Spores: A Comprehensive Guide to Air Quality Testing

You may want to see also

Conidiomata: Structures in fungi producing conidia, asexual spores for rapid propagation

Fungi have evolved diverse strategies for survival and propagation, and one of the most fascinating is the development of conidiomata—sac-like structures that produce conidia, asexual spores enabling rapid reproduction. These structures are not merely biological curiosities; they are critical for the fungi’s ability to colonize new environments, evade predators, and respond to environmental stresses. Conidiomata vary widely in shape, size, and color across fungal species, reflecting their adaptability to different ecological niches. For instance, the black dots on moldy bread are conidiomata, showcasing how these structures are integral to fungal life cycles in everyday settings.

To understand conidiomata, consider their function as spore factories. Unlike sexual spores, conidia are produced asexually, allowing fungi to multiply quickly without a mate. This efficiency is particularly advantageous in stable environments where rapid colonization is key. For example, *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* genera rely heavily on conidiomata to disperse conidia through air or water, ensuring widespread distribution. The structure of conidiomata—often flask-shaped or cushion-like—maximizes spore release, with openings (ostioles) that act as launchpads for conidia. This design highlights the precision with which fungi have evolved to optimize their reproductive strategies.

Practical applications of conidiomata extend beyond biology into agriculture, medicine, and industry. In agriculture, understanding conidiomata can help manage fungal pathogens that damage crops. For instance, *Botrytis cinerea*, the causative agent of gray mold, produces conidiomata that release spores capable of infecting a wide range of plants. By disrupting conidioma formation or spore release, farmers can reduce disease spread. Conversely, beneficial fungi like *Trichoderma* use conidiomata to produce spores that act as biocontrol agents against harmful pathogens. In medicine, conidiomata of *Aspergillus fumigatus* are studied to combat fungal infections, as their spores are a leading cause of aspergillosis in immunocompromised individuals.

For enthusiasts or researchers studying fungi, identifying conidiomata requires careful observation. Look for sac-like structures on fungal surfaces, often visible under a 10x–40x magnifying lens. Color and texture can provide clues; for example, the dark, bumpy appearance of *Cladosporium* conidiomata contrasts with the powdery, green conidiomata of *Penicillium*. Collecting samples for analysis involves sterile techniques to avoid contamination. A simple method is to place a piece of transparent tape over the fungal growth, then transfer it to a microscope slide for examination. This hands-on approach not only aids in identification but also deepens appreciation for the intricate world of fungi.

In conclusion, conidiomata are more than just spore-producing structures—they are testaments to fungal ingenuity. Their role in rapid, asexual reproduction ensures fungi’s resilience and adaptability, whether in a petri dish, a forest, or a food storage facility. By studying conidiomata, we gain insights into fungal biology and unlock practical solutions for agriculture, medicine, and beyond. Whether you’re a scientist, farmer, or curious observer, these structures offer a window into the remarkable strategies fungi employ to thrive in diverse environments.

Where to Buy Milky Spore: Top Retailers and Online Sources

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

These structures are called sporangia.

Sporangia are commonly found in plants, fungi, and some algae.

The primary function of sporangia is to produce and release spores for reproduction and dispersal.

Spores form through processes like meiosis (in plants and fungi) or asexual division (in some organisms) within the sporangia.

No, sporangia are primarily found in non-seed plants like ferns, mosses, and horsetails, as well as in fungi.