The question of whether spores are always male is a common misconception rooted in the confusion between the roles of spores in plant and fungal reproduction and the concept of gender in animals. Spores, which are reproductive units produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, are not inherently male or female. Instead, they are asexual or unicellular structures that can develop into new organisms under favorable conditions. In plants like ferns and fungi, spores are typically haploid and can grow into gametophytes, which then produce male and female gametes. Therefore, spores themselves do not have a gender; they are simply a means of reproduction that can give rise to organisms capable of producing male or female reproductive cells.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Fungal Spores: Gender Neutrality

Fungal spores challenge our traditional understanding of gender in biology. Unlike animals and many plants, fungi do not produce male or female spores. Instead, their reproductive structures release haploid cells that can fuse with compatible partners, regardless of a predefined gender role. This asexual or unisex approach to reproduction highlights the diversity of life’s strategies and raises questions about why we project human gender concepts onto organisms that operate on entirely different principles.

Consider the process of spore formation in fungi like *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*. These species produce spores through structures such as conidia or sporangiospores, which are not inherently male or female. When conditions are right, these spores germinate and grow into new individuals without requiring a mate. However, when sexual reproduction occurs, two compatible spores (often labeled "+" and "–" rather than male/female) fuse to form a zygote. This system, known as heterothallism, emphasizes compatibility over gender, demonstrating that reproductive success in fungi relies on genetic matching, not sex-based roles.

From a practical standpoint, understanding fungal spore gender neutrality is crucial in fields like agriculture and medicine. For instance, fungicides targeting spore production must account for the absence of gender-specific vulnerabilities. Similarly, in mycology labs, researchers studying spore behavior focus on environmental triggers (e.g., humidity, temperature) rather than gender-based traits. Home gardeners can apply this knowledge by creating conditions unfavorable for spore germination—such as reducing moisture levels—to control fungal growth without relying on gender-targeted interventions.

Comparing fungal spores to pollen grains in plants further underscores their gender neutrality. While pollen is often described as "male," fungal spores lack this designation. This distinction is not just semantic; it reflects fundamental differences in reproductive biology. Plants evolved separate male and female structures for pollination, whereas fungi streamlined their reproduction to prioritize adaptability and survival in diverse environments. This comparison invites us to rethink how we categorize and study reproductive mechanisms across species.

In conclusion, fungal spores exemplify nature’s capacity to innovate beyond human constructs like gender. Their unisex nature not only simplifies their reproductive cycle but also enhances their resilience in various ecosystems. By embracing this perspective, scientists and enthusiasts alike can better appreciate the complexity and elegance of fungal biology, moving away from anthropocentric frameworks that limit our understanding of life’s possibilities.

Can You Play Mouthwashing on Mac? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Plant Spores: Male vs. Female Roles

Spores, the microscopic units of reproduction in plants like ferns and fungi, defy simple categorization as male or female. Unlike animals, where sex is often binary, plants exhibit a spectrum of reproductive strategies. In spore-producing plants, the concept of male and female roles is more nuanced, tied to the production of gametes rather than the spores themselves.

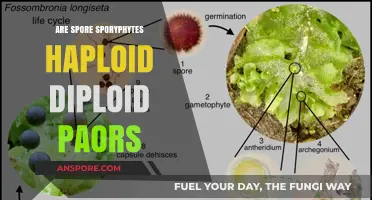

Spores are essentially single-celled organisms capable of developing into new individuals. They are produced in structures like sporangia and are typically haploid, meaning they carry half the genetic material of the parent plant. The key distinction lies not in the spores themselves, but in the type of gametes they give rise to. Some spores develop into structures that produce sperm (male gametes), while others develop into structures that produce eggs (female gametes). This division of labor is fundamental to the reproductive cycle of spore-producing plants.

Consider the life cycle of a fern, a classic example of a spore-producing plant. When a fern spore germinates, it grows into a small, heart-shaped structure called a prothallus. The prothallus is bisexual, meaning it can produce both male and female gametes. However, the spores themselves are not inherently male or female. It is only after the spore develops into a prothallus that the sex organs—antheridia (producing sperm) and archegonia (producing eggs)—form. This illustrates that the male and female roles are assigned at a later stage, not at the spore level.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this distinction is crucial for horticulture and conservation. For instance, when cultivating ferns, knowing that spores are not sex-specific allows for more efficient propagation. Gardeners can focus on creating optimal conditions for spore germination and prothallus development, rather than attempting to separate "male" and "female" spores. Similarly, in conservation efforts for endangered spore-producing plants, this knowledge helps in designing strategies that support the entire reproductive cycle, from spore dispersal to gamete production.

In conclusion, the idea that spores are always male is a misconception. Spores are neutral entities that develop into structures capable of producing either male or female gametes. This understanding not only clarifies the biology of spore-producing plants but also has practical applications in horticulture and conservation. By recognizing the flexibility and complexity of plant reproductive systems, we can better appreciate and support the diversity of life on Earth.

Understanding Spore-Producing Plants: Haploid, Diploid, or Both?

You may want to see also

Algal Spores: Asexual Reproduction

Spores are not always male, and this misconception often stems from a misunderstanding of their role in reproduction. In the context of algal spores, the focus shifts entirely to asexual reproduction, a process that challenges traditional notions of gendered reproductive structures. Algal spores, produced through methods like zoospores or aplanospores, are unicellular entities capable of developing into new individuals without fertilization. This mechanism highlights the diversity of reproductive strategies in nature, where gendered roles are irrelevant.

Consider the life cycle of *Chlamydomonas*, a green alga. Under favorable conditions, it reproduces asexually by forming zoospores, which are motile and can disperse to colonize new environments. These spores are not male or female but rather self-sufficient units of life. The process begins with the alga undergoing multiple fission within its cell wall, eventually releasing spores equipped with flagella for movement. This example underscores how asexual reproduction in algae bypasses the need for gendered gametes, emphasizing efficiency and adaptability.

From a practical standpoint, understanding algal spore reproduction is crucial for industries like aquaculture and biotechnology. For instance, cultivating algae for biofuel production often relies on optimizing asexual spore formation to ensure rapid growth and consistency. Researchers manipulate environmental factors such as light intensity, nutrient availability, and temperature to induce spore release. A key tip for cultivators is to maintain a pH range of 7.5–8.5 and provide a 12-hour light/dark cycle to maximize spore viability. This knowledge not only enhances productivity but also reduces reliance on complex sexual reproduction methods.

Comparatively, while sexual reproduction in plants and animals often involves male and female gametes, algal asexual spores represent a streamlined alternative. This contrast is particularly evident when examining the energy investment required for each strategy. Asexual reproduction in algae demands fewer resources, as it does not involve mate-seeking behaviors or the production of specialized reproductive cells. This efficiency makes it an evolutionary advantage in stable environments, where rapid proliferation is more beneficial than genetic diversity.

In conclusion, algal spores challenge the notion that reproductive structures must align with male or female categories. Their asexual nature not only simplifies the reproductive process but also offers insights into the adaptability of life forms. Whether in scientific research or industrial applications, recognizing the unique role of these spores expands our understanding of biological diversity and its practical implications. By focusing on such specific mechanisms, we uncover the elegance of nature’s solutions to survival and proliferation.

Are Spore Syringes Legal in Florida? Understanding the Current Laws

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spores in Ferns: Sex Determination

Ferns, unlike flowering plants, do not produce seeds. Instead, they reproduce via spores, tiny, single-celled structures that develop into new individuals. A common misconception is that spores are always male, but this oversimplifies the fascinating reproductive biology of ferns. In reality, fern spores are neither male nor female; they are haploid cells that give rise to a gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure that produces both sperm and eggs. This means a single spore can generate both male and female reproductive organs, challenging the binary notion of sex determination in plants.

To understand this process, consider the life cycle of a fern. When a spore lands in a suitable environment, it germinates into a gametophyte, also known as a prothallus. This gametophyte is bisexual, producing sperm in antheridia and eggs in archegonia. When water is present, sperm swim to fertilize eggs, resulting in a diploid zygote that grows into the familiar fern plant. This alternation of generations—between haploid gametophytes and diploid sporophytes—is a hallmark of fern reproduction. Thus, the spore itself is not male or female but a precursor to a structure that houses both sexes.

One practical tip for observing this process is to collect fern spores from the undersides of mature fronds, where they are often clustered in structures called sori. Place the spores on a damp, sterile medium, such as agar or soil, and maintain humidity by covering them with a clear lid. Within a few weeks, you’ll see gametophytes develop, allowing you to witness the bisexual nature of these structures firsthand. This simple experiment highlights the complexity of fern reproduction and dispels the myth that spores are inherently male.

Comparatively, this system contrasts sharply with seed plants, where pollen (male) and ovules (female) are distinct. Ferns’ approach is more fluid, with a single spore capable of initiating both male and female functions. This adaptability may explain why ferns have thrived for over 360 million years, surviving mass extinctions and colonizing diverse habitats. By studying fern spores, we gain insights into the evolutionary flexibility of plant reproductive strategies and the origins of sex determination in the plant kingdom.

In conclusion, fern spores are not always male—or female, for that matter. They are haploid cells that develop into bisexual gametophytes, blurring traditional sex distinctions. This unique reproductive mechanism underscores the diversity of life on Earth and offers a compelling example of nature’s ingenuity. Whether you’re a botanist, educator, or curious observer, exploring fern spores provides a window into the intricate world of plant biology and challenges our assumptions about sex determination.

Are Mold Spores Water Soluble? Unraveling the Science Behind It

You may want to see also

Bacterial Spores: Gender Irrelevance

Bacterial spores challenge the notion of gender relevance in biology. Unlike organisms with distinct male and female reproductive structures, bacteria reproduce asexually, rendering gender concepts inapplicable. Spores, formed by certain bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are not male or female but rather dormant, resilient survival structures. These spores withstand extreme conditions—heat, radiation, and desiccation—and reactivate when the environment becomes favorable. Understanding this gender irrelevance is crucial for fields like microbiology, medicine, and biotechnology, where spore behavior impacts sterilization, infection control, and industrial processes.

Consider the process of spore formation, or sporulation, as a survival mechanism rather than a reproductive strategy tied to gender. When nutrients deplete, some bacteria initiate sporulation, producing a single spore within the mother cell. This spore contains a copy of the bacterium’s DNA, encased in multiple protective layers, including a cortex and exosporium. No male or female gametes are involved; the process is entirely asexual. For example, *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax, forms spores that can persist in soil for decades, highlighting their role in endurance rather than gendered reproduction.

From a practical standpoint, recognizing the gender irrelevance of bacterial spores simplifies their management in clinical and industrial settings. Sterilization protocols, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes, target spore destruction because of their resistance. In healthcare, this knowledge is vital for preventing spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridioides difficile* from causing infections. Similarly, in food preservation, understanding spores’ resilience informs methods like pressure canning, which eliminates *Clostridium botulinum* spores in low-acid foods. Misapplying gendered concepts to spores could lead to ineffective strategies, underscoring the importance of this distinction.

Comparatively, fungal spores, such as those from molds and yeasts, are often mistakenly conflated with bacterial spores due to their similar role in survival. However, fungal spores can be involved in sexual or asexual reproduction, depending on the species, and may exhibit structures analogous to male and female roles. Bacterial spores, in contrast, lack any such complexity. This comparison highlights the uniqueness of bacterial spores’ gender irrelevance and reinforces the need for precise terminology in scientific discourse.

In conclusion, bacterial spores’ gender irrelevance is a fundamental biological principle with practical implications. By focusing on their asexual, survival-oriented nature, professionals can design more effective strategies for sterilization, infection control, and industrial applications. This clarity eliminates confusion and ensures that efforts are directed toward understanding spores’ true role in bacterial life cycles. Whether in a lab, hospital, or factory, recognizing this irrelevance is key to mastering spore-related challenges.

Are Mushroom Spores Legal in Canada? Understanding the Current Laws

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, spores are not always male. Spores are reproductive units produced by plants, fungi, and some microorganisms, and they can be either male, female, or asexual, depending on the organism and its reproductive strategy.

Not all plants produce male spores. Some plants, like ferns, produce both male and female spores (microspores and megaspores), while others, such as mosses, produce only one type of spore that can develop into both male and female structures.

No, spores in fungi are not always male. Fungi produce spores as part of their life cycle, and these spores can be asexual (like conidia) or sexual (like basidiospores or asci), but they are not classified as male or female.

In some organisms, spores can develop into structures that produce both male and female gametes. For example, in certain algae and bryophytes, a single spore can grow into a gametophyte that produces both sperm and eggs. However, spores themselves are not inherently male or female.