Spores, often microscopic and lightweight, are reproductive structures produced by various organisms such as fungi, bacteria, and plants. Their ability to disperse through the air raises the question: are spores considered an aerosol? Aerosols are defined as suspensions of fine solid particles or liquid droplets in a gas, typically air. Given that spores can remain suspended in the air for extended periods and travel significant distances, they fit the criteria of an aerosol. This classification is crucial in understanding their role in environmental processes, disease transmission, and atmospheric science, as it highlights their potential impact on air quality, human health, and ecological systems.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition of Spores and Aerosols: Clarify what constitutes spores and aerosols in scientific terms

- Spores as Airborne Particles: Explore if spores meet criteria to be classified as aerosols

- Size and Dispersion of Spores: Analyze spore size and how they disperse in the air

- Health and Environmental Impact: Discuss spores' effects on human health and ecosystems as aerosols

- Detection and Measurement Methods: Examine techniques to identify and quantify spores in the air

Definition of Spores and Aerosols: Clarify what constitutes spores and aerosols in scientific terms

Spores and aerosols, though often mentioned in the same breath, are distinct entities with unique characteristics and roles in science. Spores are reproductive structures produced by certain plants, algae, fungi, and bacteria, designed to survive harsh conditions and disperse over long distances. They are typically unicellular and encased in a protective shell, enabling them to remain dormant until favorable conditions trigger germination. For example, fungal spores like those from *Aspergillus* can persist in soil or air for years, waiting for moisture and warmth to sprout into new organisms. Aerosols, on the other hand, are microscopic particles or liquid droplets suspended in gas, such as air. They can range from natural entities like pollen and dust to human-made pollutants like smoke or spray droplets. Aerosols are defined by their size, typically between 0.001 and 100 micrometers, which allows them to remain airborne for extended periods. Understanding these definitions is crucial, as spores can become part of an aerosol when dispersed into the air, but not all aerosols contain spores.

To clarify further, consider the mechanisms of dispersal. Spores are inherently adapted for aerial or waterborne travel, often utilizing wind, water currents, or even animal carriers to spread. For instance, fungal spores released during dry, windy conditions can travel miles before settling. Aerosols, however, are formed through processes like evaporation, combustion, or mechanical agitation. A common example is sea spray, where wave action generates salt particles that become airborne. While spores can be a component of natural aerosols, such as in the case of fungal or bacterial spores in dust storms, they are not synonymous with aerosols. The key distinction lies in their origin and purpose: spores are reproductive units, while aerosols are a medium of transport for various particles, including but not limited to spores.

From a practical perspective, the interplay between spores and aerosols has significant implications for health and environmental science. Inhalation of spore-containing aerosols can lead to respiratory conditions like asthma or allergic reactions, particularly in individuals sensitive to fungal or pollen spores. For example, concentrations of fungal spores in indoor air exceeding 1,000 colony-forming units (CFU) per cubic meter are often associated with increased health risks. Similarly, bacterial spores, such as those from *Bacillus anthracis* (the causative agent of anthrax), can remain viable in aerosol form for days, posing bioterrorism threats. To mitigate these risks, air filtration systems with HEPA filters are recommended, as they can capture particles as small as 0.3 micrometers, effectively removing both spores and aerosolized particles from indoor environments.

A comparative analysis highlights the differences in their scientific treatment. Spores are studied under microbiology and botany, focusing on their genetic resilience, germination triggers, and ecological roles. Aerosols, however, fall under atmospheric science and physics, where researchers examine their formation, behavior, and impact on climate and air quality. For instance, while microbiologists might investigate how fungal spores survive desiccation, atmospheric scientists could model how aerosolized spores contribute to cloud formation. This interdisciplinary divide underscores the need for collaborative research to fully understand the dynamics of spores in aerosol systems, particularly in contexts like disease transmission or environmental monitoring.

In conclusion, while spores and aerosols intersect in their ability to travel through air, their definitions and functions remain distinct. Spores are specialized reproductive units, while aerosols are a broader category of suspended particles. Recognizing this difference is essential for fields ranging from public health to environmental science. Practical measures, such as air quality monitoring and filtration, can address the risks posed by spore-containing aerosols, ensuring safer indoor and outdoor environments. By clarifying these terms, scientists and practitioners can better navigate the complexities of airborne particles and their impacts on human and ecological systems.

Understanding Bacterial Spores: Formation, Function, and Survival Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Spores as Airborne Particles: Explore if spores meet criteria to be classified as aerosols

Spores, the reproductive units of fungi, bacteria, and plants, are undeniably airborne. They are lightweight, often measuring between 1 and 10 micrometers in diameter, allowing them to remain suspended in the air for extended periods. This characteristic raises the question: do spores meet the criteria to be classified as aerosols? Aerosols are defined as solid or liquid particles suspended in a gas, typically air, with sizes ranging from a few nanometers to 100 micrometers. Given their size and airborne nature, spores fall squarely within this size range, suggesting they could indeed be classified as aerosols. However, classification requires more than just size; it involves understanding their behavior, dispersion, and environmental impact.

To determine if spores qualify as aerosols, consider their dispersion mechanisms. Spores are released into the air through various processes, such as wind dispersal, human activity, or natural disturbances like wildfires. Once airborne, they can travel significant distances, influenced by air currents, humidity, and temperature. This behavior aligns with aerosol dynamics, where particles are transported and distributed across environments. For instance, fungal spores like *Aspergillus* and *Cladosporium* are commonly detected in indoor and outdoor air samples, demonstrating their ability to act as airborne particles. However, unlike engineered aerosols, spores are biological entities with unique properties, such as the ability to germinate under favorable conditions, which complicates their classification.

From a practical standpoint, treating spores as aerosols has implications for health and safety. Inhalation of certain spores, like those of *Stachybotrys chartarum* (black mold), can cause respiratory issues, allergies, or infections. Understanding spores as aerosols allows for better risk assessment and mitigation strategies. For example, in healthcare settings, HEPA filters are used to capture airborne particles, including spores, to prevent infections. Similarly, in agriculture, spore dispersal models, informed by aerosol physics, help predict fungal disease outbreaks in crops. This practical application underscores the importance of recognizing spores as aerosols, even if their biological nature sets them apart from non-living particles.

A comparative analysis highlights the similarities and differences between spores and typical aerosols. While both are airborne and within the same size range, spores possess biological functions that aerosols lack. For instance, pollen grains, another type of biological particle, are often classified as aerosols due to their airborne nature, but their role in plant reproduction distinguishes them from non-biological particles. Spores, too, have a reproductive purpose, which introduces variability in their behavior, such as dormancy or germination. This duality—being both a biological entity and an airborne particle—challenges strict classification but also enriches our understanding of their role in ecosystems and human environments.

In conclusion, spores meet the size and dispersion criteria to be classified as aerosols, yet their biological nature introduces complexities. Recognizing spores as aerosols enhances our ability to study their environmental impact, manage health risks, and develop effective control measures. Whether in healthcare, agriculture, or environmental science, this classification provides a framework for addressing the unique challenges posed by these airborne biological particles. While the debate may continue, the practical benefits of treating spores as aerosols are undeniable, offering a more comprehensive approach to understanding and managing their presence in the air.

Are Black Mold Spores Airborne? Understanding the Risks and Spread

You may want to see also

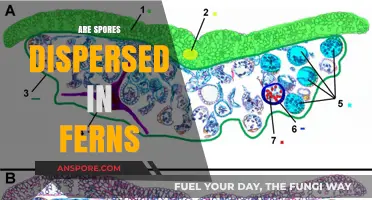

Size and Dispersion of Spores: Analyze spore size and how they disperse in the air

Spores, ranging in size from 1 to 100 micrometers, are lightweight biological particles uniquely suited for airborne dispersal. This size spectrum places them squarely within the inhalable particle range, typically defined as 0.5 to 10 micrometers for efficient respiratory deposition. Larger spores, such as those of *Aspergillus* (2–5 μm), can still remain suspended in air currents due to their low density, while smaller spores, like those of *Bacillus* (1 μm), exhibit extended aerosol lifetimes, often measured in hours or days. This size-dependent behavior is critical in understanding their role as aerosols, as it directly influences their transport, deposition, and potential health impacts.

Dispersion mechanisms for spores are as varied as their sources. Fungal spores, for instance, are often released in dry, windy conditions, where mechanical disruption of fungal structures propels them into the air. Bacterial spores, such as *Clostridium*, may become aerosolized through human activities like soil tilling or construction, where particulate matter is disturbed. Once airborne, spore dispersion is governed by environmental factors: humidity can cause spores to aggregate and settle, while temperature gradients and air turbulence enhance their vertical and horizontal transport. For example, *Alternaria* spores, common allergens, are known to travel hundreds of kilometers, aided by their lightweight structure and favorable meteorological conditions.

Analyzing spore dispersion requires a practical approach. In indoor environments, spore concentrations can be monitored using volumetric air samplers, which collect particles over time to assess exposure risks. For instance, occupational settings like agricultural facilities or laboratories may require spore counts below 1000 colony-forming units per cubic meter (CFU/m³) to ensure worker safety. Outdoors, real-time sensors and weather models predict spore movement, helping allergists issue alerts during high-spore seasons. A key takeaway is that spore size and dispersion are not just biological phenomena but actionable data points for mitigating health risks and environmental impacts.

Comparatively, spores differ from other aerosols like pollen or industrial particles in their resilience and dispersion dynamics. Unlike pollen, which is often larger (10–100 μm) and settles quickly, spores can remain aloft longer, increasing their potential for inhalation. Their small size also allows them to penetrate deep into the respiratory system, with particles under 5 μm reaching the alveolar region. This distinction underscores the need for targeted filtration strategies, such as HEPA filters (effective for particles ≥0.3 μm) in HVAC systems, to reduce indoor spore concentrations. Practical tips include using air purifiers during spore seasons and maintaining relative humidity below 50% to inhibit fungal spore growth.

In conclusion, the size and dispersion of spores are fundamental to their classification as aerosols and their impact on human health and ecosystems. From their aerodynamic properties to environmental interactions, spores exemplify the intersection of biology and physics in aerosol science. By understanding these dynamics, we can develop more effective monitoring and control measures, whether for allergen management, disease prevention, or environmental conservation. This knowledge is not just academic—it translates into actionable steps for healthier living spaces and more informed public health policies.

Are Psilocybe Spores Illegal in Washington State? Legal Insights

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Health and Environmental Impact: Discuss spores' effects on human health and ecosystems as aerosols

Spores, when suspended in the air as aerosols, can have profound and multifaceted impacts on both human health and ecosystems. These microscopic particles, produced by fungi, bacteria, and plants, are lightweight and easily dispersed, making them a significant environmental and health concern. Their ability to travel long distances and remain viable under harsh conditions amplifies their potential to affect diverse environments and populations.

Human Health Implications:

Inhalation of spore aerosols poses risks that vary depending on spore type, concentration, and individual susceptibility. For instance, fungal spores like *Aspergillus* and *Alternaria* can trigger allergic reactions, asthma exacerbations, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis, particularly in immunocompromised individuals or those with pre-existing respiratory conditions. Studies show that indoor spore concentrations above 500 colony-forming units (CFU) per cubic meter significantly increase the risk of respiratory symptoms. Occupational settings, such as agricultural or construction environments, often expose workers to higher spore levels, necessitating protective measures like N95 masks and adequate ventilation. Bacterial spores, such as those from *Bacillus anthracis* (anthrax), are less common but far more dangerous, with even minimal inhalation doses (as low as 8,000–50,000 spores) potentially causing severe illness or death.

Ecosystem Disruption:

In ecosystems, spore aerosols play a dual role—both beneficial and detrimental. Plant spores, like those from ferns and mosses, are essential for vegetation propagation and ecosystem regeneration. However, invasive fungal spores, such as *Phytophthora infestans* (the cause of late blight in potatoes), can devastate crops and native plant species, leading to biodiversity loss and economic hardship. Aquatic ecosystems are particularly vulnerable, as spore aerosols can introduce pathogens to water bodies, affecting fish and other organisms. For example, *Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis*, a fungal pathogen spread via aerosols, has contributed to the decline of amphibian populations globally.

Mitigation and Practical Tips:

Reducing the health and environmental impact of spore aerosols requires targeted strategies. For individuals, monitoring indoor humidity levels (ideally below 50%) and using HEPA filters can minimize fungal spore accumulation. In agricultural settings, crop rotation and fungicides help prevent spore-borne diseases. On a larger scale, climate change mitigation is critical, as rising temperatures and altered precipitation patterns favor spore proliferation and dispersal. Early detection systems for invasive species and public health surveillance programs can also limit the spread of harmful spores.

Comparative Perspective:

Unlike other aerosols, such as pollen or industrial pollutants, spores are living entities capable of germination and colonization. This unique characteristic makes them both resilient and adaptable, challenging traditional control methods. While pollen allergies are seasonal and predictable, spore-related health issues can occur year-round, particularly in damp or mold-prone environments. Similarly, while industrial aerosols are often localized, spores can travel across continents, making their management a global concern.

In conclusion, spore aerosols are a critical yet often overlooked environmental and health issue. Their dual nature—as both life-sustaining agents and potential pathogens—demands a nuanced approach to mitigation. By understanding their mechanisms and impacts, individuals and communities can take proactive steps to protect health and preserve ecosystems in an increasingly interconnected world.

Are Spores Always Haploid? Unraveling the Truth in Fungal Reproduction

You may want to see also

Detection and Measurement Methods: Examine techniques to identify and quantify spores in the air

Spores, being lightweight and easily dispersed, are indeed classified as aerosols, making their detection and measurement in the air a critical task across various fields, from environmental monitoring to public health. Identifying and quantifying these microscopic particles requires specialized techniques that balance precision with practicality. Below, we explore the methods, their applications, and the nuances that make them effective.

Sampling Techniques: The First Step in Detection

Air sampling is the cornerstone of spore detection. One widely used method is the impaction technique, where air is forced through a small opening onto a sticky surface or agar plate, trapping spores for analysis. For instance, the Burkard spore trap uses a 10-liter-per-minute airflow to collect spores on a petroleum jelly-coated tape, allowing for hourly monitoring. Another approach is filtration, where air is drawn through a filter (e.g., polycarbonate or glass fiber) to capture spores, which are later analyzed using microscopy or molecular methods. Each technique has its strengths: impaction is ideal for real-time monitoring, while filtration offers higher collection efficiency for low-concentration environments.

Molecular Methods: Precision in Identification

Once collected, spores must be identified and quantified. Traditional microscopy, while cost-effective, often lacks specificity, especially for closely related species. Enter molecular methods like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and quantitative PCR (qPCR), which amplify and quantify spore DNA with remarkable precision. For example, qPCR can detect as few as 10 spores per cubic meter of air, making it invaluable for allergen or pathogen monitoring. However, these methods require careful sample preparation to avoid DNA degradation, and their cost can be prohibitive for large-scale applications.

Emerging Technologies: Real-Time Monitoring and Automation

Advancements in technology are revolutionizing spore detection. Real-time PCR systems, such as the BioFire FilmArray, provide results in under an hour, enabling rapid response to outbreaks. Additionally, automated spore counters, like the SporePlay system, use laser scattering to detect and quantify spores in real time, eliminating the need for manual sampling. These technologies are particularly useful in high-risk environments, such as hospitals or agricultural settings, where immediate action is critical. However, their high initial investment and maintenance costs limit accessibility for smaller organizations.

Practical Considerations: Balancing Accuracy and Feasibility

Choosing the right detection method depends on the context. For instance, in allergen monitoring, a combination of impaction sampling and ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) can provide both quantitative and qualitative data on pollen spores. In contrast, pathogen detection in healthcare settings may prioritize qPCR for its sensitivity. Regardless of the method, calibration and regular maintenance of equipment are essential to ensure accurate results. For example, spore traps should be cleaned weekly to prevent clogging, and PCR reagents must be stored at -20°C to maintain efficacy.

Takeaway: A Multifaceted Approach for Effective Monitoring

Detecting and quantifying spores in the air is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor. By combining sampling techniques with advanced analytical methods, researchers and practitioners can achieve both accuracy and efficiency. Whether monitoring for allergens, pathogens, or environmental indicators, the key lies in selecting tools that align with specific needs while addressing practical constraints. As technology continues to evolve, the future promises even more innovative solutions for this critical task.

Sporangia vs. Spores: Understanding the Difference in Fungal Reproduction

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, spores can be considered an aerosol when they are suspended in the air as tiny particles, typically ranging from 1 to 100 micrometers in size.

Spores become airborne through natural processes like wind dispersal, human activities such as disturbing soil or plants, or mechanical systems like HVAC units that circulate air.

Most spores, including those from fungi, bacteria, and plants, can form an aerosol if they are light enough and conditions (e.g., wind, humidity) are favorable for their dispersal.

Inhaling spore aerosols can pose health risks, such as allergic reactions, asthma exacerbations, or infections, depending on the type of spore and the individual's immune system.