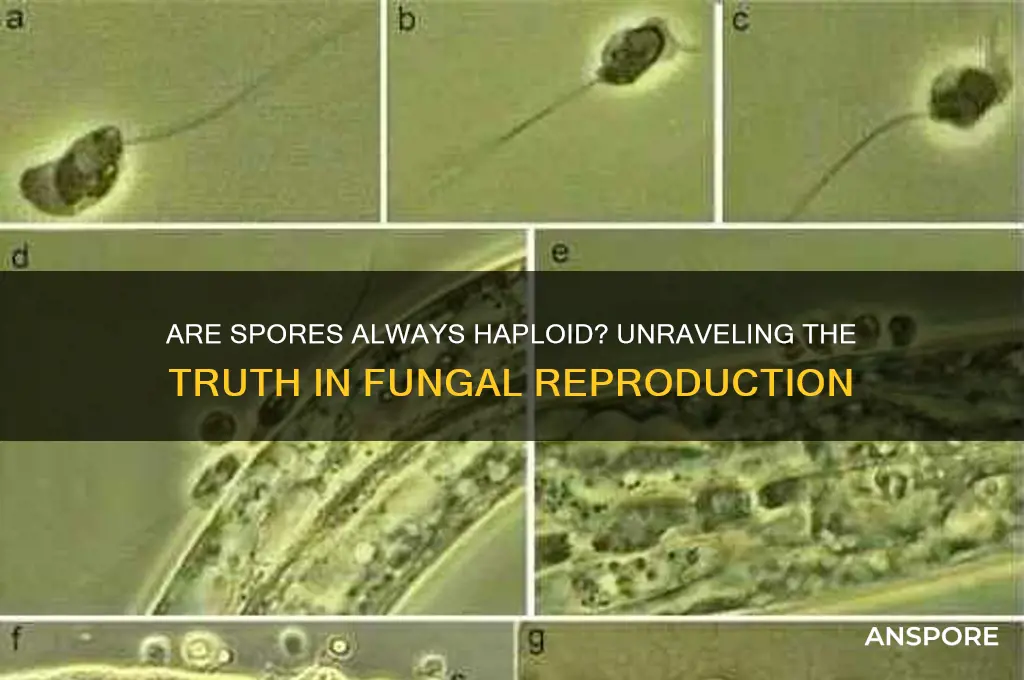

Spores are a critical reproductive structure in many organisms, particularly in fungi, plants, and some protists, serving as a means of dispersal and survival in adverse conditions. A common assumption is that spores are always haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes. However, this is not universally true. While many spores, such as those produced by ferns and fungi during their life cycles, are indeed haploid, others can be diploid or even polyploid, depending on the organism and the specific stage of its reproductive cycle. For instance, in certain algae and some fungi, spores may retain a diploid state, challenging the simplistic view that all spores are haploid. Understanding the ploidy of spores is essential for grasping the complexities of life cycles and reproductive strategies across different biological kingdoms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Are spores always haploid? | No, spores are not always haploid. |

| Haploid spores | Produced in haploid organisms (e.g., fungi, some plants) via meiosis. |

| Diploid spores | Found in some algae and fungi (e.g., zygospores in Zygomycota). |

| Examples of haploid spores | Fungal spores (conidia, ascospores, basidiospores), pollen grains. |

| Examples of diploid spores | Zygospores in Zygomycota, some algal spores. |

| Role of haploid spores | Dispersal, survival, and reproduction in haploid life cycle phases. |

| Role of diploid spores | Result from fertilization, often for survival in harsh conditions. |

| Life cycle context | Depends on the organism's life cycle (haploid-dominant vs. diploid-dominant). |

| Exceptions | Some organisms produce both haploid and diploid spores at different stages. |

| Significance | Reflects diversity in reproductive strategies across kingdoms. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spores in Fungi: Most fungal spores are haploid, produced via meiosis for genetic diversity

- Plant Spores: Haploid spores in plants (e.g., ferns) develop into gametophytes

- Bacterial Spores: Endospores in bacteria are diploid, serving as survival structures

- Algal Spores: Haploid spores in algae are common, but some species produce diploid spores

- Exceptions in Nature: Certain organisms produce diploid spores, challenging the haploid generalization

Spores in Fungi: Most fungal spores are haploid, produced via meiosis for genetic diversity

Fungal spores are predominantly haploid, a characteristic that sets them apart from many other reproductive structures in the biological world. This haploid nature is not arbitrary; it is a strategic adaptation that ensures genetic diversity and survival in varying environments. Unlike diploid cells, which carry two sets of chromosomes, haploid spores contain only one set, making them lighter and more efficient for dispersal. This simplicity in genetic composition allows fungi to colonize new habitats rapidly, a critical advantage in ecosystems where resources are often scarce and competition is fierce.

The production of haploid spores in fungi is achieved through meiosis, a specialized cell division process that reduces the chromosome number by half. Meiosis is not merely a mechanism for reproduction but a tool for innovation. By shuffling genetic material during meiosis, fungi generate spores with unique combinations of traits. This genetic diversity is essential for adapting to environmental challenges, such as temperature fluctuations, nutrient availability, and predation. For instance, a single fungal species can produce spores that vary in their ability to withstand drought or resist toxins, increasing the species' overall resilience.

Consider the practical implications of this process in agriculture and medicine. Fungal spores' haploid nature makes them ideal candidates for genetic studies and biotechnological applications. Researchers can manipulate haploid spores more easily than diploid cells, allowing for precise genetic modifications. This has led to advancements in biofuel production, where fungi are engineered to break down plant material efficiently, and in medicine, where fungal enzymes are used to synthesize drugs. Understanding the haploid state of spores also aids in controlling fungal pathogens, as targeted treatments can disrupt their reproductive cycles.

However, the haploid nature of fungal spores is not without its challenges. Haploid organisms are more susceptible to genetic mutations, which can sometimes lead to detrimental effects. Fungi mitigate this risk through mechanisms like parasexual cycles, where haploid cells temporarily fuse to repair damaged DNA before returning to the haploid state. This balance between genetic diversity and stability highlights the sophistication of fungal reproductive strategies. For gardeners and farmers, recognizing this duality is crucial; while spores' haploid nature promotes beneficial traits, it also requires vigilant management to prevent harmful mutations from spreading.

In conclusion, the haploid nature of most fungal spores is a testament to the evolutionary ingenuity of fungi. Produced via meiosis, these spores embody a delicate balance between genetic diversity and adaptability. Whether in natural ecosystems, agricultural settings, or biotechnological labs, understanding this characteristic provides valuable insights into fungal biology and its applications. By appreciating the role of haploid spores, we can harness their potential while mitigating their risks, ensuring a harmonious coexistence with these ubiquitous organisms.

Bug Types and Spore Immunity: Debunking Myths in Pokémon Battles

You may want to see also

Plant Spores: Haploid spores in plants (e.g., ferns) develop into gametophytes

Spores in the plant kingdom, particularly those of ferns, serve as a fascinating example of haploid development. These microscopic, single-celled structures are produced by the sporophyte generation and are genetically haploid, containing only one set of chromosomes. When conditions are favorable, a fern spore germinates and grows into a gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure that is the sexual phase of the fern's life cycle. This gametophyte is not only haploid but also independent, capable of photosynthesis and survival in its own right. It is on this gametophyte that the male and female reproductive organs develop, setting the stage for the next generation.

Consider the process of spore germination in ferns as a delicate dance of environmental cues and genetic programming. For successful development, spores require specific conditions: adequate moisture, moderate temperatures, and a suitable substrate. Once germinated, the spore grows into a filamentous structure called a protonema, which eventually gives rise to the mature gametophyte. This entire process underscores the adaptability and resilience of haploid spores, which can remain dormant for extended periods, waiting for the right conditions to initiate growth.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the haploid nature of plant spores is crucial for horticulture and conservation. For instance, fern enthusiasts often cultivate these plants from spores, a process that requires patience and precision. Spores are typically sown on a sterile medium, such as a mixture of peat and perlite, and kept in a humid environment with indirect light. Over several weeks, the spores germinate and develop into gametophytes, which can then be transferred to a more permanent growing medium. This method not only allows for the propagation of rare fern species but also provides a hands-on way to observe the unique life cycle of these plants.

Comparing plant spores to those of fungi reveals both similarities and differences. While fungal spores are also often haploid, they typically serve as agents of dispersal and colonization rather than developing into a distinct sexual phase. In contrast, plant spores like those of ferns have a clear developmental trajectory, growing into gametophytes that are essential for sexual reproduction. This distinction highlights the diversity of spore functions across different organisms, even when they share a common haploid characteristic.

In conclusion, the development of haploid spores into gametophytes in plants like ferns is a remarkable biological process that combines simplicity and complexity. It showcases the elegance of plant life cycles, where a single cell can give rise to a structure capable of both independent survival and sexual reproduction. For anyone interested in botany, horticulture, or simply the wonders of nature, the journey of a fern spore from dormancy to gametophyte offers invaluable insights into the intricacies of plant life.

Are Mold Spores Harmful? Understanding Health Risks and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Bacterial Spores: Endospores in bacteria are diploid, serving as survival structures

Bacterial endospores challenge the assumption that all spores are haploid. Unlike the haploid spores of fungi and plants, which are produced through meiosis and carry a single set of chromosomes, bacterial endospores are diploid, retaining the full genetic complement of the parent cell. This distinction is crucial for understanding their function and survival mechanisms. Endospores are not reproductive structures but rather highly resistant, dormant forms that enable bacteria to withstand extreme conditions such as heat, desiccation, and radiation. Their diploid nature ensures genetic stability during prolonged dormancy, a feature essential for their role as survival structures.

The formation of endospores, or sporulation, is a complex, multi-step process triggered by nutrient deprivation. During sporulation, the bacterial cell divides asymmetrically, producing a smaller cell (the forespore) within a larger mother cell. The forespore eventually develops into the mature endospore, encased in multiple protective layers, including a cortex rich in dipicolinic acid and a proteinaceous coat. These layers contribute to the endospore’s remarkable resilience, allowing it to remain viable for centuries under adverse conditions. For example, *Bacillus anthracis* endospores have been isolated from soil samples over 100 years old, demonstrating their longevity.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the diploid nature of endospores is vital for industries such as food preservation and medical sterilization. Endospores of bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum* and *Bacillus cereus* are notorious for surviving standard cooking temperatures, posing risks of foodborne illness. To ensure safety, food processing techniques such as autoclaving (121°C for 15–30 minutes) or the use of high-pressure processing (HPP) are employed to destroy these resilient structures. Similarly, in healthcare settings, surgical instruments are sterilized using methods specifically designed to eliminate endospores, as standard disinfectants may be ineffective.

Comparatively, the diploid endospores of bacteria contrast sharply with the haploid spores of fungi and plants, which are primarily involved in reproduction and dispersal. While fungal spores, such as those of *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind or water, bacterial endospores are heavier and remain localized, waiting for favorable conditions to germinate. This difference highlights the distinct evolutionary strategies of these organisms. Bacterial endospores prioritize survival over dispersal, reflecting their adaptation to unpredictable and harsh environments.

In conclusion, bacterial endospores defy the generalization that all spores are haploid. Their diploid nature, combined with their intricate protective mechanisms, underscores their role as ultimate survival structures. For professionals in fields ranging from microbiology to food safety, recognizing this uniqueness is essential for developing effective strategies to control or utilize these remarkable entities. Whether in the lab, the kitchen, or the clinic, the diploid endospore remains a testament to the ingenuity of bacterial survival.

Cotton Grass: Flowering Conifer or Spore Producer? Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$14.19 $14.99

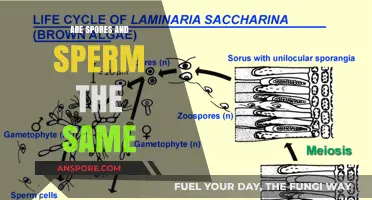

Algal Spores: Haploid spores in algae are common, but some species produce diploid spores

Spores, often associated with fungi and plants, are not universally haploid, and algae provide a fascinating counterpoint to this assumption. In the diverse world of algae, the production of spores is a critical aspect of their life cycle, offering insights into the variability of reproductive strategies in the plant kingdom. While haploid spores are indeed prevalent in many algal species, the existence of diploid spores challenges the notion of a one-size-fits-all approach to spore classification.

Consider the life cycle of *Chlamydomonas*, a well-studied genus of green algae. Here, the dominant phase is haploid, and spores are typically produced through asexual reproduction, maintaining the haploid state. This aligns with the common perception of spores as haploid entities. However, in certain environmental conditions, *Chlamydomonas* can undergo sexual reproduction, resulting in the formation of a diploid zygote. Although this zygote can function as a spore, it remains diploid until it germinates and undergoes meiosis, highlighting a deviation from the haploid norm.

In contrast, red algae, such as *Porphyra*, exhibit a more complex life cycle involving alternation of generations. In this cycle, both haploid and diploid phases are multicellular, and spores can be produced from either phase. Tetraspores, for instance, are haploid spores formed through meiosis, while carpospores are diploid spores resulting from fertilization. This dual spore production strategy underscores the adaptability of algal reproductive systems and the need to approach spore classification with nuance.

The production of diploid spores in algae is not merely an anomaly but a strategic response to environmental pressures. Diploid spores often exhibit greater resilience to harsh conditions, such as desiccation or extreme temperatures, compared to their haploid counterparts. For example, in *Ulva* (sea lettuce), diploid spores (zoospores) are more robust and can survive longer in unfavorable environments, ensuring the species' persistence. This adaptive advantage may explain why some algal species favor diploid spore production under specific circumstances.

Understanding the variability in algal spore ploidy has practical implications, particularly in aquaculture and biotechnology. For instance, when cultivating algae for biofuel production, knowing whether a species produces haploid or diploid spores can influence cultivation strategies. Haploid spores may be preferred for rapid growth and high biomass production, while diploid spores might be selected for their hardiness in outdoor cultivation systems. Thus, the study of algal spores not only enriches our understanding of plant biology but also informs applied sciences, demonstrating the importance of recognizing exceptions to general biological rules.

Does Rain Increase Mold Spores? Understanding the Link Between Rain and Mold

You may want to see also

Exceptions in Nature: Certain organisms produce diploid spores, challenging the haploid generalization

Spores, often associated with fungi and plants, are typically understood to be haploid structures, carrying a single set of chromosomes. However, nature, in its boundless creativity, presents exceptions that defy this generalization. Certain organisms produce diploid spores, challenging our assumptions and revealing the complexity of reproductive strategies. These exceptions are not mere anomalies but rather adaptations that offer unique advantages in specific environments.

Consider the case of some basidiomycetes, a group of fungi that includes mushrooms and rusts. Unlike their haploid counterparts, these fungi produce diploid spores through a process known as karyogamy, where two haploid nuclei fuse before spore formation. This diploid state persists until meiosis occurs, often in response to environmental cues. For instance, the mushroom *Coprinus cinereus* maintains diploid spores, which allow for rapid growth and resilience in nutrient-poor soils. This adaptation highlights how diploidy can confer stability and robustness in challenging conditions.

Another striking example is found in certain algae, such as *Chlamydomonas reinhardtii*. Under stress, this single-celled alga can produce diploid spores, known as zygospores, through the fusion of two haploid gametes. These diploid spores remain dormant until conditions improve, ensuring survival during harsh periods. This strategy underscores the evolutionary advantage of diploidy in enhancing stress tolerance and long-term viability.

To understand the implications of these exceptions, consider the following steps: First, recognize that diploid spores often arise in response to environmental pressures, such as nutrient scarcity or extreme temperatures. Second, note that these spores typically undergo meiosis before germination, restoring the haploid state in the next generation. Finally, appreciate that these exceptions are not random but rather finely tuned adaptations that optimize survival and reproduction in specific ecological niches.

In practical terms, studying these exceptions can inform agricultural and conservation efforts. For example, understanding how diploid spores contribute to fungal resilience could lead to new strategies for crop protection. Similarly, insights into algal zygospores might inspire innovations in biofuel production or environmental remediation. By embracing these exceptions, we gain a deeper appreciation for the diversity of life and the ingenuity of nature’s solutions.

Challenges in Sterilizing Spore-Forming Bacteria: Effective Methods Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, spores are not always haploid. While many spores, such as those produced by fungi and plants during alternation of generations, are haploid, some organisms produce diploid spores, such as certain fungi like basidiomycetes during their life cycle.

Haploid refers to cells or organisms that have a single set of chromosomes, typically represented as "n." In the context of spores, haploid spores are produced by meiosis and contain half the number of chromosomes of the parent organism.

Yes, spores can be diploid. For example, zygospores in certain fungi and some algal spores are diploid, meaning they have two sets of chromosomes (2n).

Most spores in plants and fungi are haploid because they are produced during the sexual phase of their life cycle via meiosis. This ensures genetic diversity when the spores germinate and grow into gametophytes, which then produce gametes for sexual reproduction.

Bacterial spores are neither haploid nor diploid because bacteria are typically haploid organisms with a single set of chromosomes. Spores in bacteria, such as endospores, are formed as a survival mechanism and retain the same ploidy as the parent cell.