Spores are a critical reproductive structure in many organisms, particularly in fungi, plants, and some protists, but they are not typically considered multicellular organisms themselves. Instead, spores are usually haploid, single-celled entities that serve as a means of dispersal and survival in adverse conditions. In the context of whether spores are haploid multicellular organisms, the answer is generally no, as they are predominantly unicellular. However, there are exceptions, such as in certain fungal species where spores can develop into multicellular structures under specific conditions. Understanding the nature of spores—whether haploid or diploid, and whether unicellular or multicellular—is essential for grasping their role in the life cycles of various organisms and their ecological significance.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Ploidy | Haploid (contain a single set of chromosomes) |

| Cellularity | Typically unicellular, though some spores can develop into multicellular structures (e.g., fungal hyphae or plant gametophytes) |

| Function | Reproductive units for dispersal and survival in adverse conditions |

| Origin | Produced by meiosis in diploid organisms (e.g., fungi, plants, some bacteria) |

| Examples | Fungal spores, plant spores (e.g., ferns, mosses), bacterial endospores |

| Multicellular Development | Some spores (e.g., fungal and plant spores) can germinate into multicellular organisms under favorable conditions |

| Survival Mechanism | Dormant and resistant to harsh environments (e.g., heat, desiccation, chemicals) |

| Dispersal | Spread by wind, water, animals, or other means to colonize new habitats |

| Genetic Variation | Haploid nature allows for genetic recombination during sexual reproduction in some organisms |

| Size | Microscopic, ranging from a few micrometers to several hundred micrometers |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition of Spores: Spores are reproductive units produced by plants, algae, fungi, and some bacteria

- Haploid Nature: Spores are typically haploid, carrying a single set of chromosomes

- Multicellularity: Most spores are unicellular, but some organisms produce multicellular spore structures

- Life Cycle Role: Spores play a key role in dispersal, survival, and reproduction in many organisms

- Examples of Spores: Examples include fungal spores, fern spores, and bacterial endospores

Definition of Spores: Spores are reproductive units produced by plants, algae, fungi, and some bacteria

Spores are microscopic, often single-celled structures that serve as a survival and dispersal mechanism for various organisms, including plants, algae, fungi, and certain bacteria. These reproductive units are not merely miniature versions of the parent organism but are specialized for resilience and propagation. For instance, fungal spores, such as those from *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, can withstand extreme conditions like desiccation, high temperatures, and UV radiation, allowing them to persist in environments where the parent organism cannot. This adaptability makes spores a critical component of their life cycle, ensuring species survival across generations.

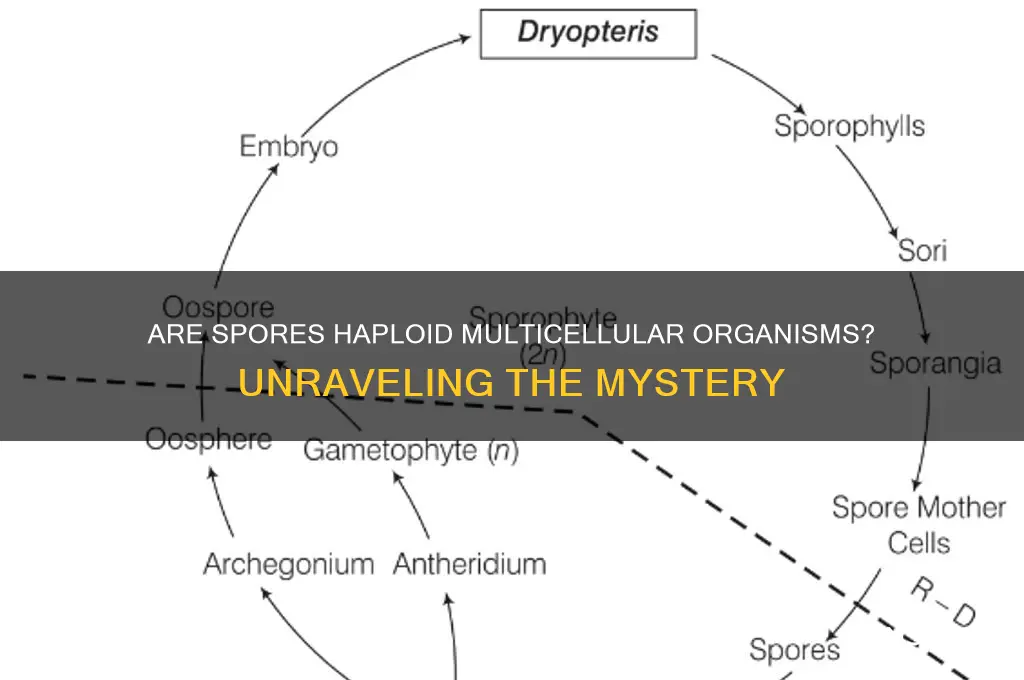

To understand whether spores are haploid multicellular organisms, it’s essential to dissect their genetic composition. Most spores, particularly those of fungi and plants, are haploid, meaning they carry a single set of chromosomes. This haploid state is a strategic evolutionary adaptation, enabling rapid reproduction and genetic diversity when spores germinate and fuse with others. For example, in ferns, haploid spores grow into gametophytes, which produce gametes for sexual reproduction. However, the term "multicellular" rarely applies to spores, as they are typically unicellular or consist of a few cells at most. Exceptions exist, such as the multicellular spores of some algae, but these are not the norm.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore biology has significant implications, especially in fields like agriculture, medicine, and environmental science. For instance, farmers use fungal spores as bioinoculants to enhance soil health and plant growth, while medical professionals study spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum* to develop vaccines and treatments. To harness spores effectively, consider their environmental requirements: fungal spores germinate optimally at 20–30°C and 70–90% humidity, while plant spores often require specific light conditions. Always handle spores with care, especially those of pathogenic organisms, using sterile techniques and personal protective equipment to prevent contamination.

Comparatively, spores differ from seeds in their structure, function, and resilience. While seeds are multicellular, nutrient-rich structures that develop into new plants, spores are lightweight, nutrient-poor, and designed for dispersal and survival. For example, a dandelion seed contains an embryo, endosperm, and protective coat, whereas a fungal spore is a single cell encased in a durable wall. This distinction highlights the unique role of spores in their respective life cycles, emphasizing their efficiency in colonizing new habitats. By studying these differences, scientists can develop targeted strategies for spore control, such as using fungicides to inhibit fungal spore germination in crops.

In conclusion, spores are not typically haploid multicellular organisms but rather haploid, often unicellular structures optimized for survival and reproduction. Their genetic simplicity and environmental resilience make them fascinating subjects of study and valuable tools in various applications. Whether you’re a gardener combating fungal infections or a researcher exploring spore biology, understanding their definition and characteristics is key to leveraging their potential effectively. Always approach spore-related tasks with precision and caution, ensuring both safety and success in your endeavors.

Exploring the Presence of Spores in Human DNA: Fact or Fiction?

You may want to see also

Haploid Nature: Spores are typically haploid, carrying a single set of chromosomes

Spores, the reproductive units of many plants, fungi, and some protozoans, are predominantly haploid, meaning they carry a single set of chromosomes. This genetic simplicity is a cornerstone of their survival strategy, enabling rapid reproduction and adaptation in diverse environments. Unlike diploid cells, which contain two sets of chromosomes, haploid spores require only one successful division to form a new organism, streamlining their lifecycle and enhancing their resilience.

Consider the lifecycle of ferns, a classic example of spore-producing plants. After a fern releases spores, each haploid spore germinates into a tiny, heart-shaped gametophyte. This gametophyte, despite its small size, is a fully functional, independent organism. It produces gametes (sperm and eggs) through mitosis, which then fuse to form a diploid zygote. This zygote grows into the familiar fern plant, completing the cycle. The haploid nature of spores ensures genetic diversity, as the fusion of gametes from different gametophytes introduces new combinations of traits.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the haploid nature of spores is crucial for horticulture and agriculture. For instance, mushroom farmers cultivate haploid spores to grow mycelium, the vegetative part of fungi, which eventually produces fruiting bodies. By controlling environmental factors like humidity and temperature, farmers can optimize spore germination and mycelium growth. Similarly, in plant breeding, haploid spores are used to create hybrid varieties with desirable traits, such as disease resistance or higher yield.

Comparatively, the haploid state of spores contrasts sharply with the diploid cells of most multicellular organisms. While diploid cells provide stability and redundancy, haploid spores prioritize flexibility and efficiency. This trade-off is evident in their ecological roles: spores can survive harsh conditions, such as drought or extreme temperatures, by remaining dormant until favorable conditions return. Their simplicity allows them to disperse widely, colonizing new habitats with minimal energy expenditure.

In conclusion, the haploid nature of spores is a key to their success as reproductive units. It enables rapid reproduction, genetic diversity, and adaptability, making spores indispensable in both natural ecosystems and human applications. Whether in the wild or in controlled environments, understanding and harnessing this trait can lead to innovations in agriculture, conservation, and biotechnology. By focusing on their unique genetic makeup, we can unlock the full potential of these microscopic powerhouses.

Spore Syringe Shelf Life: Fridge Storage Duration Explained

You may want to see also

Multicellularity: Most spores are unicellular, but some organisms produce multicellular spore structures

Spores, often associated with plants and fungi, are typically unicellular structures designed for dispersal and survival in harsh conditions. However, a fascinating exception exists: some organisms produce multicellular spore structures, challenging the conventional understanding of spore biology. These multicellular spores, though rare, offer unique insights into the evolution of complexity and the strategies organisms employ to ensure survival.

Consider the case of certain algae, such as *Volvox*, which forms multicellular spores called zygotes. Unlike their unicellular counterparts, these zygotes consist of multiple cells working in concert. This multicellularity enhances their resilience, allowing them to withstand environmental stresses more effectively. For instance, the collective cellular machinery can repair damage or maintain metabolic functions that a single cell might struggle to sustain. This example highlights how multicellular spore structures can provide evolutionary advantages, particularly in unpredictable environments.

From a practical standpoint, understanding multicellular spores has implications for fields like agriculture and biotechnology. For example, multicellular spores in fungi, such as those in the genus *Basidiomycota*, play a crucial role in nutrient cycling and ecosystem health. Farmers and researchers can leverage this knowledge to develop more effective fungicides or promote beneficial fungal growth in soil. Similarly, in biotechnology, multicellular spore structures could inspire the design of resilient synthetic organisms capable of surviving extreme conditions, such as those found in space exploration.

Comparatively, the distinction between unicellular and multicellular spores underscores the diversity of reproductive strategies in the natural world. While unicellular spores prioritize simplicity and efficiency, multicellular spores invest in complexity to gain long-term survival benefits. This trade-off illustrates the balance between energy expenditure and survival potential, a recurring theme in biology. By studying these differences, scientists can uncover principles that apply across species, from microorganisms to multicellular life forms.

In conclusion, while most spores are unicellular, the existence of multicellular spore structures adds a layer of complexity to our understanding of life’s strategies for survival and reproduction. These exceptions not only challenge biological norms but also offer practical applications in agriculture, biotechnology, and beyond. By examining these unique cases, we gain a deeper appreciation for the ingenuity of nature and the potential it holds for human innovation.

Do All Fungi Develop Exclusively from Spores? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Life Cycle Role: Spores play a key role in dispersal, survival, and reproduction in many organisms

Spores are nature's survival capsules, engineered for resilience and dispersal. These microscopic, often single-celled structures are produced by plants, fungi, and some protozoa to endure harsh conditions—drought, extreme temperatures, or nutrient scarcity. Unlike seeds, which are multicellular and contain stored food, spores are typically haploid, carrying half the genetic material of the parent organism. This simplicity is their strength: it allows them to remain dormant for years, even centuries, until conditions are favorable for growth. For example, fern spores can survive in soil for decades, waiting for the right combination of moisture and light to germinate. This adaptability makes spores a critical mechanism for the survival and persistence of species across generations.

Consider the role of spores in dispersal, a process essential for colonizing new habitats. Fungi, such as mushrooms, release billions of spores into the air, carried by wind or water to distant locations. This strategy ensures genetic diversity and reduces competition in crowded environments. Similarly, plant spores, like those of mosses and ferns, are lightweight and easily transported, enabling these organisms to thrive in diverse ecosystems, from tropical rainforests to arid deserts. Even in aquatic environments, algae like *Chlamydomonas* produce spores that can withstand desiccation, allowing them to survive in temporary water bodies. This dispersal capability highlights spores as nature's solution to the challenge of geographic isolation.

Reproduction through spores is a testament to their efficiency and versatility. In fungi, for instance, spores are the primary means of asexual reproduction, allowing rapid colonization of new areas. When a spore lands in a suitable environment, it germinates, grows, and produces a new organism, often within days. This process is particularly vital for organisms in unpredictable environments, where traditional reproductive methods may fail. For example, bread mold (*Rhizopus*) can produce spores within 24 hours under optimal conditions, ensuring its survival in fluctuating habitats. This rapid reproductive cycle underscores the spore's role as a life-sustaining mechanism.

However, the spore's role in survival is not without challenges. While their hardy structure protects them from environmental stressors, it also limits their immediate growth potential. Spores require specific triggers—such as water, warmth, or light—to activate, and their success depends on landing in a suitable environment. For instance, *Bacillus* spores, commonly found in soil, can survive extreme conditions but must germinate in nutrient-rich conditions to thrive. This duality—resilience paired with dependency—illustrates the delicate balance spores maintain in their life cycle.

In practical terms, understanding spores can inform strategies in agriculture, conservation, and medicine. Farmers can harness spore-producing fungi, like *Trichoderma*, to protect crops from pathogens. Conservationists can use spore banks to preserve endangered plant species, ensuring their genetic material survives for future restoration efforts. Even in medicine, spores of *Bacillus subtilis* are used as probiotics, leveraging their durability to deliver health benefits. By studying spores, we unlock tools for sustainability, biodiversity, and innovation, highlighting their indispensable role in both natural and human-engineered systems.

Spores vs. Pollen: Unraveling the Differences in Plant Reproduction

You may want to see also

Examples of Spores: Examples include fungal spores, fern spores, and bacterial endospores

Spores are a fascinating survival mechanism employed by various organisms, but not all spores are created equal. Let's delve into three distinct examples: fungal spores, fern spores, and bacterial endospores, each showcasing unique adaptations to their environments.

Fungal Spores: Masters of Dispersal

Fungi, the silent decomposers of our ecosystems, rely heavily on spores for reproduction and dispersal. These microscopic structures are typically haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes. Imagine a dandelion puffball – fungal spores are like those tiny seeds, carried by wind, water, or even insects to colonize new territories. For instance, the common bread mold, *Aspergillus*, produces vast quantities of spores that can travel through the air, landing on bread and initiating the familiar fuzzy growth. This ability to disperse widely allows fungi to thrive in diverse environments, from damp forests to the confines of our kitchens.

Fungal spores are incredibly resilient, capable of surviving harsh conditions like drought and extreme temperatures. This resilience is crucial for their survival, enabling them to persist until favorable conditions return.

Fern Spores: Ancient Survivors

Ferns, ancient plants that predate dinosaurs, have a unique life cycle involving two distinct phases: a sporophyte (spore-producing) generation and a gametophyte (gamete-producing) generation. Fern spores are haploid, like fungal spores, and are produced in structures called sporangia on the underside of fern fronds. These spores are incredibly lightweight and can be dispersed by wind over long distances. Upon landing in a suitable environment, a fern spore germinates into a tiny, heart-shaped gametophyte, which then produces gametes (sperm and eggs) to continue the life cycle. This alternation of generations is a hallmark of ferns and other non-seed plants, showcasing a different evolutionary strategy compared to flowering plants.

The delicate, lacy fronds of ferns belie the toughness of their spores. These spores can remain viable for years, waiting for the right conditions to sprout and initiate a new fern plant.

Bacterial Endospores: Dormant Survivors

Bacteria, the microscopic workhorses of our planet, have evolved a remarkable survival strategy in the form of endospores. Unlike the spores of fungi and ferns, endospores are not involved in reproduction but rather serve as a dormant, highly resistant form of the bacterium. Endospores are formed within the bacterial cell in response to harsh environmental conditions like nutrient depletion or extreme temperatures. They are incredibly resilient, capable of withstanding boiling temperatures, radiation, and even the vacuum of space. This extreme durability allows bacteria to survive in environments that would be lethal to their active forms.

While not all spores are multicellular, they all share a common purpose: ensuring the survival and propagation of their respective organisms. From the airborne dispersal of fungal spores to the ancient life cycle of ferns and the extreme resilience of bacterial endospores, spores are a testament to the ingenuity of life's strategies for persistence. Understanding these diverse examples highlights the remarkable adaptability of organisms in the face of environmental challenges.

Spore Prints vs. Liquid Culture: Which Method Yields Better Results?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores are typically haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes, but they are generally unicellular, not multicellular.

Yes, spores can germinate and develop into multicellular organisms, such as in fungi and plants, through processes like vegetative growth or sporophyte formation.

No, spores can be produced by both unicellular and multicellular organisms, such as bacteria, fungi, plants, and some protists.