The question of whether spores are found in human DNA is a fascinating yet complex topic that bridges the realms of microbiology, genetics, and evolutionary biology. Spores, typically associated with plants, fungi, and certain bacteria, are reproductive structures designed for survival and dispersal. While humans do not produce spores, there is ongoing scientific inquiry into whether traces of spore-related genetic material could exist within the human genome. This exploration often delves into the possibility of horizontal gene transfer, where genetic material from one organism is incorporated into another, potentially leaving remnants of spore-related genes in human DNA. Additionally, the human microbiome, which includes fungi and bacteria capable of producing spores, raises questions about indirect interactions between spores and human genetic material. Understanding this relationship could shed light on evolutionary connections, immune responses, and even medical implications, making it a compelling area of study.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spores in Human Genome Sequences: Investigating if spore-related genes or sequences exist in human DNA

- Fungal Spores and Human DNA: Exploring potential interactions between fungal spores and human genetic material

- Horizontal Gene Transfer: Examining if spore-related genes could transfer to human DNA

- Contamination in DNA Studies: Assessing if spores contaminate human DNA samples in research

- Immune Response to Spores: Studying how human DNA responds to spore exposure immunologically

Spores in Human Genome Sequences: Investigating if spore-related genes or sequences exist in human DNA

The human genome, a complex blueprint of our biology, has been extensively studied, yet certain mysteries remain. One intriguing question arises: Do spore-related genes or sequences exist within human DNA? This inquiry delves into the possibility of ancient evolutionary connections or hidden biological mechanisms. By examining the human genome for spore-associated elements, scientists aim to uncover whether such structures, typically linked to plants, fungi, and bacteria, have left any trace in our genetic makeup.

To investigate this, researchers employ advanced bioinformatics tools to scan the human genome for sequences resembling those involved in spore formation or function. These tools compare human DNA against known spore-related genes from other organisms, searching for similarities or homologous regions. For instance, genes responsible for sporulation in fungi, such as those encoding spore coat proteins or germination factors, are of particular interest. If significant matches are found, they could suggest evolutionary conservation or horizontal gene transfer events.

However, interpreting these findings requires caution. Even if spore-related sequences are identified, their presence does not necessarily imply functionality. Many DNA segments in the human genome are remnants of evolutionary history, often referred to as "junk DNA" or pseudogenes. These sequences may have lost their original purpose but remain embedded in our genetic code. Therefore, further experiments, such as gene expression studies or functional assays, would be essential to determine if these sequences play any active role in human biology.

From a practical standpoint, understanding whether spore-related genes exist in humans could have implications for medical research. For example, if humans possess dormant spore-like mechanisms, they might offer insights into cellular resilience or survival strategies. This knowledge could inspire new therapies for conditions involving cellular stress, such as aging or neurodegenerative diseases. Additionally, it might shed light on how humans interact with spore-producing pathogens, potentially informing vaccine development or antimicrobial strategies.

In conclusion, the exploration of spore-related sequences in the human genome is a fascinating intersection of evolutionary biology and genomics. While the presence of such sequences remains speculative, their discovery could open new avenues for scientific inquiry and practical applications. As genomic technologies advance, this investigation underscores the importance of continuing to probe the depths of our DNA for hidden connections to the broader biological world.

Understanding Bacterial Spores: Formation, Function, and Survival Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Fungal Spores and Human DNA: Exploring potential interactions between fungal spores and human genetic material

Fungal spores are ubiquitous in the environment, and their interaction with human biology is a topic of growing interest. While spores themselves are not found within human DNA, recent research suggests that fungal components, such as DNA fragments or metabolites, may transiently interact with human genetic material under specific conditions. For instance, individuals with compromised immune systems or those exposed to high concentrations of fungal spores (e.g., in agricultural or mold-prone environments) may exhibit trace amounts of fungal DNA in their systems. This raises questions about the potential for fungal spores to influence human genetic processes, either directly or indirectly.

Analyzing the mechanisms of interaction, fungal spores can release enzymes and other bioactive molecules upon germination, which may affect human cells. For example, fungal proteases and nucleases could theoretically degrade or modify human DNA if they gain access to intracellular environments. However, the human body’s defense systems, including the skin, mucous membranes, and immune responses, typically prevent such interactions. Exceptions occur in cases of invasive fungal infections, where fungal elements may enter the bloodstream and interact with host cells. Studies on *Candida albicans* and *Aspergillus fumigatus* have shown that these fungi can release extracellular vesicles containing DNA, proteins, and lipids, which could potentially be taken up by human cells and influence gene expression.

To explore these interactions practically, researchers often use in vitro models, such as human cell lines exposed to controlled doses of fungal spores or their extracts. For instance, exposing epithelial cells to 10^6 spores/mL of *Aspergillus* for 24 hours has been shown to induce changes in host gene expression related to inflammation and immune response. Such experiments highlight the importance of dosage and exposure duration in determining the extent of fungal-human DNA interactions. For individuals concerned about environmental exposure, practical tips include using HEPA filters to reduce indoor spore counts, wearing masks in high-risk areas, and maintaining proper ventilation to minimize inhalation of fungal particles.

Comparatively, the interaction between fungal spores and human DNA differs significantly from bacterial or viral interactions due to the eukaryotic nature of fungi. Unlike bacteria or viruses, fungi share many cellular processes with humans, making their interactions more complex. For example, fungal DNA is less likely to integrate into the human genome but may still influence epigenetic modifications or trigger immune responses that indirectly affect genetic processes. This distinction underscores the need for targeted research into fungal-human interactions, particularly in the context of chronic diseases like asthma, allergies, and fungal infections, where repeated exposure to spores may play a role.

In conclusion, while fungal spores are not inherently found within human DNA, their potential to interact with human genetic material is a fascinating and underexplored area of research. From enzymatic activity to immune modulation, the mechanisms by which fungi may influence human DNA are multifaceted and context-dependent. For those at risk, proactive measures to limit spore exposure, coupled with ongoing scientific inquiry, are essential to understanding and mitigating any potential impacts on human health.

Unveiling the Unique Appearance of Morel Spores: A Visual Guide

You may want to see also

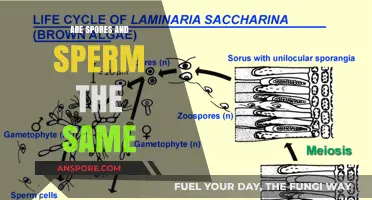

Horizontal Gene Transfer: Examining if spore-related genes could transfer to human DNA

Spores, the resilient survival structures of certain bacteria, fungi, and plants, are not inherently part of human DNA. However, the concept of horizontal gene transfer (HGT) raises intriguing questions about whether spore-related genes could theoretically integrate into the human genome. HGT, a process where genetic material moves between organisms without reproduction, is well-documented in bacteria and has been observed in eukaryotes, including plants and animals. While there is no evidence of spore-specific genes in humans, understanding the mechanisms and potential pathways of HGT is crucial for exploring this possibility.

To examine this, consider the steps required for HGT to occur. First, spore-related genes would need to be released from their protective spore structure, typically triggered by environmental stress or germination. Second, these genes must enter human cells, a process that could occur through phagocytosis, endocytosis, or direct DNA uptake. Third, the foreign DNA would need to integrate into the human genome, a rare event requiring specific enzymes like transposases or viral vectors. Finally, the integrated genes would need to be expressed and provide a selective advantage to be retained over generations. While each step is individually plausible, the cumulative probability remains low, especially given the complexity of the human immune system and DNA repair mechanisms.

A comparative analysis of existing HGT examples provides insight. For instance, *Lactococcus lactis*, a bacterium used in cheese production, has acquired genes from other bacteria through HGT, enhancing its metabolic capabilities. Similarly, rotifers, microscopic aquatic animals, have incorporated foreign genes from fungi, algae, and bacteria, potentially aiding their adaptability. However, these cases involve organisms with simpler genomes and less stringent DNA regulation compared to humans. The human genome’s robust defense mechanisms, including methylation and histone modification, make it highly resistant to foreign DNA integration. Thus, while HGT is biologically feasible, the transfer of spore-related genes into humans remains speculative.

From a practical standpoint, exploring this hypothesis could have implications for biotechnology and medicine. If spore-related genes were to confer benefits, such as enhanced stress resistance or metabolic efficiency, synthetic biology could engineer such transfers. For example, CRISPR-Cas9 technology could be used to insert spore-derived genes into human cells for research purposes. However, ethical and safety concerns must be addressed, including the risk of unintended mutations or immune reactions. Researchers must also consider dosage—how much foreign DNA can be introduced without disrupting cellular function? Current studies suggest that small, targeted gene inserts (e.g., 1-5 kb) are more feasible than large-scale transfers.

In conclusion, while spores are not found in human DNA, the concept of HGT opens a fascinating avenue for exploration. The process requires a series of unlikely events, from spore gene release to human genome integration, but is not biologically impossible. Comparative examples and advancements in genetic engineering provide a framework for investigating this phenomenon. However, practical applications must navigate ethical, safety, and technical challenges, ensuring that any potential benefits outweigh the risks. As research progresses, the line between speculation and possibility may continue to blur, offering new insights into the dynamic nature of genetic exchange.

Are Botulism Spores Airborne? Unraveling the Truth and Risks

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Contamination in DNA Studies: Assessing if spores contaminate human DNA samples in research

Spores, resilient structures produced by certain bacteria, fungi, and plants, are ubiquitous in the environment. Their durability allows them to survive harsh conditions, raising concerns about their potential to contaminate sensitive biological samples, including human DNA. In DNA research, even minute contamination can skew results, leading to misinterpretations of genetic data. This issue is particularly critical in fields like forensic science, microbiome studies, and clinical diagnostics, where accuracy is paramount.

To assess whether spores contaminate human DNA samples, researchers must employ rigorous protocols. First, pre-PCR cleanrooms should be utilized to minimize environmental exposure. These facilities maintain stringent air filtration and surface decontamination standards, reducing the likelihood of spore introduction. Second, negative controls are essential in every experiment. These controls, which include sterile water or blank swabs, help identify contamination by comparing them to experimental samples. If spore DNA is detected in controls, the entire batch may be compromised.

A critical step in contamination assessment involves quantitative PCR (qPCR) to detect spore-specific markers. For instance, fungal spores can be identified using primers targeting the ITS (Internal Transcribed Spacer) region of ribosomal DNA. Bacterial spores, such as those from *Bacillus* species, can be detected using primers for the *spo0A* gene. Threshold cycle (Ct) values below 35 indicate significant contamination, warranting sample exclusion from analysis. Additionally, next-generation sequencing (NGS) can provide a broader picture by identifying diverse spore species, though this method is more resource-intensive.

Despite these measures, contamination can still occur, particularly in studies involving low-biomass samples, such as ancient DNA or trace forensic evidence. In such cases, physical separation techniques, like density gradient centrifugation, can help isolate human DNA from spore contaminants. However, these methods are not foolproof and may reduce overall DNA yield. Researchers must weigh the trade-offs between contamination risk and sample integrity, often requiring replication of experiments to ensure reliability.

Finally, documentation and transparency are vital in addressing contamination. Labs should maintain detailed records of sample handling, including environmental conditions and personnel involved. Publishing raw data and contamination assessments alongside findings fosters reproducibility and allows the scientific community to evaluate the robustness of the results. By adopting these practices, researchers can mitigate the impact of spore contamination on DNA studies, ensuring the accuracy and credibility of their work.

Exploring Spore Drives: Fact or Fiction in Modern Science?

You may want to see also

Immune Response to Spores: Studying how human DNA responds to spore exposure immunologically

Spores, the resilient reproductive units of fungi and certain bacteria, are ubiquitous in our environment. While they are not inherently part of human DNA, exposure to spores can trigger complex immune responses that involve genetic and epigenetic changes. Understanding how human DNA responds immunologically to spore exposure is crucial for addressing allergies, infections, and potential therapeutic applications.

Analyzing the Immune Cascade: From Recognition to Response

When spores enter the human body, they are immediately flagged as foreign by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on immune cells, such as dendritic cells and macrophages. These receptors identify spore-specific molecules like chitin or β-glucans, initiating a signaling cascade. This process activates genes involved in inflammation, such as those encoding interleukins (e.g., IL-6, IL-8) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). For instance, inhalation of *Aspergillus fumigatus* spores can lead to a dose-dependent increase in IL-6 production, with concentrations as low as 10^4 spores/mL triggering measurable immune activity in vitro. Epigenetic modifications, such as histone acetylation, further amplify gene expression, ensuring a rapid and robust immune response.

Practical Tips for Minimizing Spore-Induced Immune Activation

For individuals with spore sensitivities, such as those with asthma or allergic rhinitis, reducing exposure is key. HEPA filters can remove up to 99.97% of airborne spores, particularly in indoor environments. Wearing N95 masks during outdoor activities in high-spore seasons (e.g., fall for fungal spores) can also mitigate inhalation. Additionally, maintaining indoor humidity below 50% discourages spore germination, as many fungi require moisture to transition from dormant to active states. For children under 12, whose immune systems are still developing, these measures are especially critical, as their DNA may be more susceptible to epigenetic changes from repeated spore exposure.

Comparative Insights: Immune Responses Across Age Groups

The immune response to spores varies significantly by age. In adults, repeated exposure often leads to immune tolerance, where regulatory T cells suppress excessive inflammation. In contrast, infants and the elderly exhibit heightened susceptibility due to immature or weakened immune systems, respectively. For example, infants exposed to high levels of *Penicillium* spores (e.g., >10^3 spores/m³) are at increased risk of developing asthma by age 5. Conversely, elderly individuals may experience chronic inflammation from spore exposure, contributing to conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Tailoring interventions to age-specific immune profiles—such as probiotic supplementation for infants or anti-inflammatory medications for seniors—can optimize outcomes.

Persuasive Argument for Further Research: Unlocking Therapeutic Potential

Studying the human DNA response to spores is not merely academic; it holds promise for innovative therapies. For instance, spore-derived molecules like chitin nanoparticles are being explored as vaccine adjuvants, enhancing immune responses to pathogens. Similarly, understanding how spores modulate epigenetic markers could inform treatments for autoimmune diseases, where immune regulation is dysregulated. By investing in this research, we can transform spores from environmental nuisances into tools for improving human health.

The interplay between human DNA and spore exposure is a dynamic, multifaceted process with profound implications for immunity and disease. From practical prevention strategies to cutting-edge therapeutic applications, this field demands attention. Whether you’re a researcher, clinician, or individual seeking to protect your health, understanding this immune response is the first step toward harnessing its potential.

Understanding Spores: Haploid or Diploid? Unraveling the Genetic Mystery

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, spores are not found in human DNA. Spores are reproductive structures produced by certain plants, fungi, and bacteria, and they are not part of human genetic material.

Human DNA does not contain spore-like structures. DNA in humans is organized into chromosomes and genes, which are distinct from the structures found in spore-producing organisms.

There is no direct connection between spores and human genetics. Spores are unrelated to human DNA, as they serve a reproductive function in other organisms, not in humans.

Spores from other organisms cannot integrate into human DNA. Human DNA is highly protected and regulated, preventing foreign genetic material like spores from becoming part of it.

Humans do not have genetic mechanisms similar to spore formation. Spore formation is a specialized process unique to certain plants, fungi, and bacteria, and humans lack such reproductive structures.