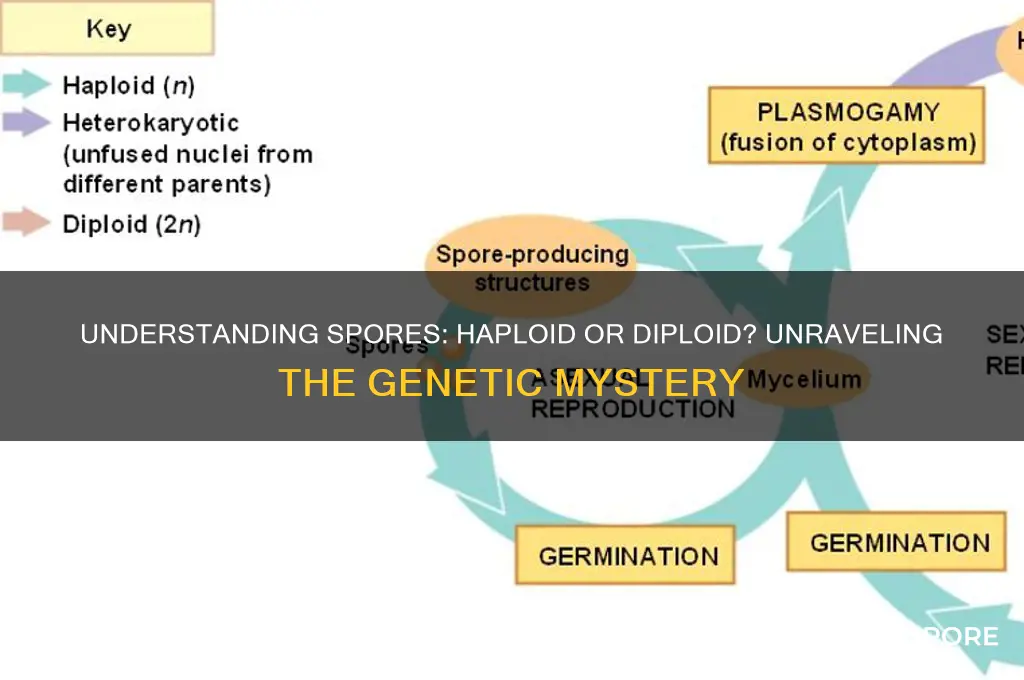

Spores are a critical reproductive structure in many organisms, particularly in plants, fungi, and some protists, serving as a means of dispersal and survival in adverse conditions. A fundamental question regarding spores is whether they are haploid or diploid, which depends on the life cycle of the organism in question. In most fungi and non-vascular plants, spores are typically haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes and are produced by meiosis. However, in some vascular plants, such as ferns, spores are also haploid, while in others, like certain algae, spores can be diploid, containing two sets of chromosomes. Understanding the ploidy of spores is essential for grasping the reproductive strategies and life cycles of these diverse organisms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Nature of Spores | Spores can be either haploid or diploid, depending on the organism and life cycle stage. |

| Haploid Spores | Produced in haploid organisms (e.g., fungi, some plants) via meiosis; contain a single set of chromosomes (n). |

| Diploid Spores | Produced in diploid organisms (e.g., some algae, certain fungi) via mitosis; contain two sets of chromosomes (2n). |

| Function in Life Cycle | Haploid spores typically germinate into gametophytes, while diploid spores germinate into sporophytes. |

| Examples | Haploid: Fungal spores, bryophyte spores. Diploid: Some algal spores, certain fungal spores (e.g., in Basidiomycetes). |

| Reproduction Type | Haploid spores are often part of alternation of generations, while diploid spores may be part of a diploid-dominant life cycle. |

| Genetic Composition | Haploid (n) vs. Diploid (2n) determines the genetic makeup of the resulting organism. |

| Common Organisms | Haploid: Fungi, mosses, ferns. Diploid: Some algae, certain fungi, and a few plant species. |

Explore related products

$14.08 $14.99

What You'll Learn

- Spores in Fungi: Most fungal spores are haploid, produced via meiosis for genetic diversity

- Plant Spores: Haploid spores in plants (e.g., ferns) develop into gametophytes

- Bacterial Spores: Diploid bacterial spores (endospores) form for survival, not reproduction

- Algal Spores: Haploid spores in algae are common, aiding in asexual reproduction

- Spores vs. Gametes: Spores are haploid like gametes but develop into multicellular structures

Spores in Fungi: Most fungal spores are haploid, produced via meiosis for genetic diversity

Fungal spores, the microscopic units of dispersal and survival, are predominantly haploid, a characteristic that sets them apart in the microbial world. This haploid nature is not arbitrary; it is a strategic adaptation that ensures genetic diversity and resilience in fungal populations. Unlike diploid cells, which carry two sets of chromosomes, haploid spores contain a single set, making them lighter, more efficient for dispersal, and primed for rapid colonization under favorable conditions. This simplicity in genetic structure is a cornerstone of fungal life cycles, enabling them to thrive in diverse environments, from soil to decaying matter.

The production of haploid spores in fungi is a direct result of meiosis, a specialized cell division process that reduces the chromosome number by half. Meiosis is not merely a reproductive mechanism but a tool for innovation. By shuffling genetic material through crossing over and independent assortment, fungi generate spores with unique combinations of traits. This genetic diversity is critical for survival, allowing fungal populations to adapt to changing environments, resist pathogens, and exploit new ecological niches. For instance, the black mold *Aspergillus niger* produces haploid spores that can withstand extreme conditions, ensuring its persistence in harsh habitats.

Consider the practical implications of this haploid strategy. In agriculture, understanding spore genetics helps in managing fungal diseases. For example, the haploid spores of *Botrytis cinerea*, a pathogen causing gray mold in crops, can rapidly evolve resistance to fungicides. Farmers and researchers must therefore employ integrated pest management strategies, rotating fungicides and promoting genetic diversity in crops to counter this adaptability. Similarly, in biotechnology, haploid fungal spores are harnessed for their ability to produce enzymes and secondary metabolites, such as penicillin from *Penicillium* species, which are vital in medicine and industry.

A comparative analysis highlights the contrast between fungal spores and those of plants. While plant spores can be haploid (e.g., pollen) or diploid (e.g., zygotes), fungi overwhelmingly favor haploid spores as their primary dispersal units. This difference underscores the distinct evolutionary pressures shaping these organisms. Fungi, often decomposers or symbionts, benefit from a life cycle that maximizes genetic variation and dispersal efficiency. In contrast, plants, rooted in one place, invest more in diploid structures for stability and growth. This divergence illustrates how the haploid nature of fungal spores is tailored to their ecological roles.

In conclusion, the haploid identity of most fungal spores is a masterstroke of evolutionary efficiency. Produced via meiosis, these spores embody genetic diversity, enabling fungi to colonize, adapt, and survive in dynamic environments. From agricultural challenges to biotechnological advancements, understanding this haploid strategy offers practical insights and solutions. By studying these microscopic units, we unlock not just the secrets of fungal biology but also tools for addressing real-world problems, from crop protection to drug discovery.

Optimal Timing for Planting Morel Spores: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Plant Spores: Haploid spores in plants (e.g., ferns) develop into gametophytes

Spores in plants, particularly in ferns, mosses, and other non-seed plants, are unequivocally haploid. This means each spore contains a single set of chromosomes, a genetic blueprint halved from the parent plant. Understanding this haploid nature is crucial because it underpins the entire life cycle of these organisms, driving their reproductive strategies and ecological adaptations.

Consider the fern, a quintessential example of a plant reliant on haploid spores. When a fern releases spores, each one is a lightweight, single-celled entity capable of being carried by wind or water. Upon landing in a suitable environment, the spore germinates and grows into a gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure often no larger than a fingernail. This gametophyte is also haploid and serves as the sexual reproductive stage of the plant. It produces gametes—sperm and eggs—that, when united, form a diploid zygote, which then develops into a new fern plant. This alternation between haploid and diploid generations is a hallmark of the plant kingdom, known as the alternation of generations.

The development of gametophytes from haploid spores is not just a biological curiosity but a survival mechanism. Gametophytes are typically short-lived and dependent on moisture for sperm to swim to the egg, which is why ferns and mosses thrive in damp environments. This vulnerability is balanced by the sheer number of spores produced, ensuring that at least some find favorable conditions to grow. For instance, a single fern can release millions of spores in a season, a strategy that maximizes the chances of successful reproduction despite the odds.

Practical observations of this process can be enlightening. If you’ve ever collected fern spores for gardening, you’ll know they’re fine, dust-like particles that require careful handling. To cultivate a gametophyte, sprinkle spores on a moist, sterile medium like agar or soil kept in a humid environment. Within weeks, you’ll see tiny green gametophytes emerge, a visible testament to the haploid-to-diploid transition. This hands-on approach not only deepens understanding but also highlights the delicate balance required for these plants to thrive.

In contrast to seed plants, which produce diploid seeds directly, the haploid spore-to-gametophyte pathway in ferns and mosses is a relic of ancient plant evolution. It reflects a time when plants were more dependent on water for reproduction and less adapted to arid conditions. Yet, this system persists because it works—ferns, for example, have survived for over 360 million years. Their success lies in the simplicity and efficiency of haploid spores, which, despite their fragility, ensure genetic diversity and adaptability in changing environments. By studying these plants, we gain insights into the fundamental principles of plant biology and the resilience of life itself.

Unveiling the Invisible: What Mold Spores Look Like Under Microscope

You may want to see also

Bacterial Spores: Diploid bacterial spores (endospores) form for survival, not reproduction

Bacterial spores, specifically endospores, are a remarkable survival mechanism in the microbial world. Unlike spores in fungi or plants, which are typically haploid and play a role in reproduction, bacterial endospores are diploid and serve a fundamentally different purpose. These structures are not formed for reproduction but rather as a means of enduring harsh environmental conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, and chemical exposure. This distinction highlights the unique evolutionary strategy of bacteria, which prioritizes survival over reproductive dissemination in challenging environments.

To understand the diploid nature of bacterial endospores, consider the process of their formation, known as sporulation. During sporulation, a bacterial cell divides asymmetrically, producing a smaller cell (the forespore) within a larger mother cell. The forespore then undergoes a series of morphological and biochemical changes, including the synthesis of a protective coat and the accumulation of dipicolinic acid, which stabilizes the spore’s DNA. Crucially, the DNA within the endospore remains diploid, retaining the full genetic complement of the original cell. This ensures that when conditions improve and the spore germinates, the resulting bacterium is genetically identical to its parent, preserving its adaptive traits.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the diploid nature of bacterial endospores is essential for industries such as food safety, healthcare, and environmental management. For instance, endospores of *Clostridium botulinum* and *Bacillus anthracis* can survive extreme heat and disinfection processes, posing significant risks in food processing and bioterrorism scenarios. To mitigate these risks, specific protocols are employed, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes, which effectively destroys endospores by denaturing their proteins and degrading their DNA. This underscores the importance of targeting the resilient diploid structure of endospores in sterilization efforts.

Comparatively, the diploid nature of bacterial endospores contrasts sharply with haploid spores in other organisms. For example, fungal spores, such as those of *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, are haploid and primarily function in reproduction and dispersal. This difference reflects the distinct ecological roles of bacteria and fungi, with bacteria relying on endospores for survival in extreme conditions and fungi using spores for colonization and genetic diversity. Such comparisons illuminate the diversity of spore strategies across the biological kingdom and emphasize the specialized role of diploid bacterial endospores.

In conclusion, bacterial endospores are diploid structures formed for survival, not reproduction, representing a unique adaptation in the microbial world. Their ability to withstand extreme conditions hinges on their diploid DNA and robust protective mechanisms. For professionals in fields ranging from microbiology to public health, recognizing this distinction is critical for developing effective strategies to control and eliminate endospores in various contexts. By focusing on their diploid nature and survival function, we gain deeper insights into the resilience of bacteria and the challenges they pose in both natural and engineered environments.

Do HEPA Filters Effectively Remove Mold Spores from Indoor Air?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Algal Spores: Haploid spores in algae are common, aiding in asexual reproduction

Spores in algae are predominantly haploid, a characteristic that plays a pivotal role in their reproductive strategies. Unlike diploid spores, which carry two sets of chromosomes, haploid spores contain a single set, making them genetically simpler and more versatile. This haploid nature is a key adaptation in algae, enabling rapid and efficient asexual reproduction. When environmental conditions are favorable, these spores can quickly develop into new individuals without the need for fertilization, ensuring the species' survival and proliferation.

Consider the life cycle of *Chlamydomonas*, a common green alga. Under stress, such as nutrient depletion, it produces haploid zoospores equipped with flagella for mobility. These spores can disperse to new habitats, germinate, and grow into identical copies of the parent organism. This process, known as vegetative reproduction, highlights the efficiency of haploid spores in maintaining genetic consistency while allowing for rapid colonization of suitable environments. The simplicity of haploid genetics reduces the risk of mutations and ensures that successful traits are passed on unchanged.

From a practical standpoint, understanding haploid spores in algae has significant implications for biotechnology and aquaculture. For instance, in the cultivation of *Spirulina*, a blue-green alga rich in protein and vitamins, haploid spores are used to ensure uniform growth and high yield. Farmers can manipulate environmental conditions, such as light and temperature, to induce spore formation and subsequent growth. This method is particularly useful in mass production, where consistency and predictability are critical. By harnessing the natural asexual reproduction mechanisms of haploid spores, industries can optimize algal growth for food, biofuel, and pharmaceutical applications.

Comparatively, the use of haploid spores in algae contrasts with the reproductive strategies of more complex organisms, where diploid spores or seeds are common. In plants, for example, diploid spores (meiospores) are produced during sexual reproduction, leading to genetic diversity. Algae, however, prioritize rapid proliferation over genetic variation, especially in stable environments. This distinction underscores the evolutionary trade-offs between adaptability and efficiency, with haploid spores in algae representing a specialized solution to their ecological niche.

In conclusion, the prevalence of haploid spores in algae is a testament to their evolutionary success in asexual reproduction. These spores offer a streamlined genetic blueprint, enabling quick response to environmental cues and efficient colonization. Whether in natural ecosystems or industrial applications, the unique characteristics of algal spores provide valuable insights into reproductive biology and practical tools for harnessing algal potential. By studying these microscopic structures, we gain a deeper appreciation for the diversity of life strategies and their applications in science and technology.

Can You Play Mouthwashing on Mac? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Spores vs. Gametes: Spores are haploid like gametes but develop into multicellular structures

Spores and gametes share a fundamental characteristic: both are haploid, meaning they carry a single set of chromosomes. This haploid nature is crucial for their roles in the life cycles of organisms, particularly in plants and fungi. However, the developmental paths of spores and gametes diverge significantly. While gametes—such as sperm and egg cells—fuse during fertilization to form a diploid zygote, spores bypass this fusion step. Instead, spores directly develop into multicellular structures, such as gametophytes in plants or mycelium in fungi, without requiring a partner cell. This distinction highlights a key evolutionary adaptation: spores enable organisms to propagate and survive in diverse environments independently, whereas gametes are specialized for sexual reproduction.

Consider the life cycle of a fern as an illustrative example. After a fern releases spores, each spore germinates into a small, heart-shaped gametophyte. This gametophyte is a multicellular organism that produces both sperm and egg cells. When fertilization occurs, the resulting zygote grows into a new fern plant. Here, the spore’s haploid nature ensures genetic diversity through subsequent sexual reproduction, while its ability to develop into a gametophyte showcases its unique role in bridging asexual and sexual phases of the life cycle. This process contrasts sharply with gametes, which are solely reproductive units and do not develop into multicellular structures on their own.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the difference between spores and gametes is essential in fields like agriculture, mycology, and conservation biology. For instance, in mushroom cultivation, spores are used to initiate mycelium growth, which eventually produces fruiting bodies. Knowing that spores are haploid and capable of independent development allows cultivators to optimize conditions for spore germination and mycelium expansion. Similarly, in plant breeding, recognizing the role of spores in producing gametophytes helps breeders manipulate genetic traits more effectively. This knowledge also aids in preserving endangered species, as spores can be stored in seed banks and later cultivated to restore populations.

A persuasive argument can be made for the evolutionary advantage of spores over gametes in certain contexts. Spores’ ability to develop into multicellular structures without fertilization allows organisms to colonize new habitats rapidly, even in the absence of mates. This asexual mode of reproduction is particularly beneficial in stable environments or when sexual partners are scarce. In contrast, gametes’ reliance on fertilization limits their utility to environments where mates are readily available. For example, fungi often release vast quantities of spores to ensure at least some land in favorable conditions, a strategy that has contributed to their success in nearly every ecosystem on Earth.

In conclusion, while spores and gametes share haploidy, their developmental trajectories and ecological roles differ markedly. Spores’ capacity to grow into multicellular structures independently makes them versatile tools for survival and propagation, whereas gametes are specialized for sexual reproduction. This distinction not only enriches our understanding of biological diversity but also has practical implications for fields ranging from agriculture to conservation. By appreciating these differences, we can harness the unique properties of spores and gametes to advance both scientific knowledge and applied technologies.

Exploring Nature's Strategies: How Spores Travel and Disperse Effectively

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores are typically haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes.

Spores are produced through meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in haploid cells.

In some organisms, such as certain fungi, spores can be diploid if they are produced through mitosis or if the organism has a diploid life cycle phase.

Haploid spores germinate and grow into haploid individuals (gametophytes) that produce gametes, which then fuse to form a diploid zygote, completing the life cycle.

In alternation of generations, haploid spores develop into gametophytes, which produce gametes that fuse to form a diploid zygote. The zygote then grows into a diploid sporophyte, which produces haploid spores, completing the cycle.