Ferns are unique plants that reproduce through spores rather than seeds, setting them apart from flowering plants. Unlike the familiar process of pollination and seed formation, ferns produce tiny, dust-like spores on the undersides of their fronds, typically in clusters called sori. These spores are dispersed by wind or water, and under the right conditions, they germinate into a small, heart-shaped structure called a prothallus. The prothallus then facilitates the sexual reproduction of ferns, ultimately growing into a new fern plant. This ancient method of reproduction has allowed ferns to thrive for millions of years, making them one of the most successful and widespread plant groups on Earth.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do ferns produce spores? | Yes |

| Type of reproduction | Asexual (via spores) |

| Location of spore production | Underside of fertile fronds (leaf-like structures) |

| Structures producing spores | Sori (clusters of sporangia) |

| Sporangia function | Produce and contain spores |

| Spore dispersal methods | Wind, water, or animals |

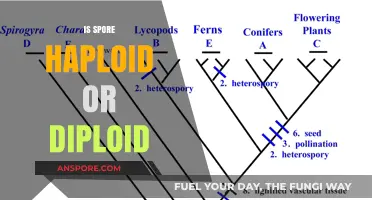

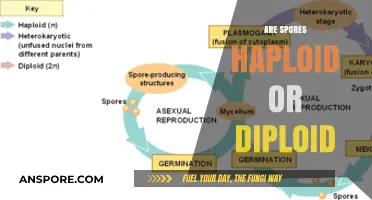

| Life cycle stage | Sporophyte (diploid) produces spores; gametophyte (haploid) grows from spores |

| Gametophyte characteristics | Small, heart-shaped, and photosynthetic |

| Spores per sporangium | Varies by species, typically hundreds to thousands |

| Spore size | Microscopic, usually 20-60 micrometers in diameter |

| Ecological role of spores | Allows ferns to colonize new habitats and survive harsh conditions |

| Examples of spore-producing ferns | Boston Fern, Maidenhair Fern, Bracken Fern |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Fern Life Cycle Overview: Spores are key to fern reproduction, starting their life cycle

- Sporangia Formation: Spores develop in clusters called sporangia on fern leaves

- Spores Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, and animals aid in spreading fern spores widely

- Germination Process: Spores grow into gametophytes, the sexual stage of ferns

- Environmental Factors: Humidity, light, and temperature influence spore production and viability

Fern Life Cycle Overview: Spores are key to fern reproduction, starting their life cycle

Ferns, unlike flowering plants, do not produce seeds. Instead, their life cycle hinges on spores—tiny, single-celled reproductive units that are both lightweight and resilient. These spores are produced in structures called sporangia, typically found on the undersides of fern fronds. When released, spores disperse through wind or water, demonstrating an efficient strategy for colonization across diverse environments. This spore-driven reproduction is a defining feature of ferns, setting them apart from seed-bearing plants and highlighting their ancient evolutionary lineage.

The life cycle of a fern is a fascinating alternation between two distinct generations: the sporophyte and the gametophyte. The sporophyte, the familiar fern plant we see, produces spores through meiosis. Once a spore lands in a suitable environment, it germinates into a gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure often just a few millimeters in size. This gametophyte is bisexual, producing both sperm and eggs. For fertilization to occur, water is essential, as sperm must swim to reach the egg. This dependency on moisture explains why ferns thrive in humid, shaded habitats.

After fertilization, the resulting zygote develops into a new sporophyte, completing the cycle. This alternation of generations is a hallmark of ferns and other non-seed plants. The gametophyte stage is short-lived and often goes unnoticed, yet it is critical for the continuation of the species. Without it, spores would remain isolated, unable to develop into the next generation. This intricate process underscores the importance of spores as the starting point and linchpin of the fern life cycle.

Practical observation of this cycle can be rewarding for gardeners and nature enthusiasts. To witness spore production, examine mature fern fronds for clusters of sporangia, often visible as brown dots on the leaf underside. For those interested in propagation, collecting spores and sowing them in a moist, shaded area can yield gametophytes within weeks. However, patience is key, as the transition from gametophyte to sporophyte can take months. Understanding this cycle not only deepens appreciation for ferns but also informs successful cultivation and conservation efforts.

In comparison to seed-producing plants, ferns’ reliance on spores presents both advantages and challenges. Spores’ small size and durability allow ferns to colonize hard-to-reach areas, but their dependence on water for fertilization limits their distribution to moist environments. This contrast highlights the evolutionary trade-offs ferns have made, adapting to specific ecological niches. By studying their life cycle, we gain insights into the diversity of plant reproductive strategies and the resilience of these ancient plants in a changing world.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: Crafting Liquid Culture from Spores

You may want to see also

Sporangia Formation: Spores develop in clusters called sporangia on fern leaves

Ferns, unlike flowering plants, rely on spores for reproduction, and these spores develop in specialized structures called sporangia. These sporangia are typically found on the undersides of fern leaves, often in clusters that give the foliage a distinctive, dotted appearance. This arrangement is not random; it is a strategic adaptation to maximize spore dispersal. When mature, the sporangia release spores into the air, where they can be carried by wind to new locations, ensuring the fern’s survival and propagation. Understanding this process is key to appreciating the unique reproductive cycle of ferns.

The formation of sporangia is a precise and intricate process. It begins with the development of spore-producing cells within the leaf tissue. Over time, these cells differentiate into sporangia, which are protected by a layer of cells that eventually dry out and split open, releasing the spores. This mechanism is highly efficient, allowing ferns to thrive in diverse environments, from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands. For gardeners or enthusiasts looking to propagate ferns, recognizing the presence of sporangia is a clear indicator that the plant is healthy and reproductively active.

From a practical standpoint, observing sporangia can also help in identifying fern species. Different ferns produce sporangia in distinct patterns, such as along the veins or in circular clusters called sori. For example, the Maidenhair fern (Adiantum) has sori along the edges of its leaflets, while the Boston fern (Nephrolepis) has them in rows beneath the leaves. By noting these variations, one can accurately classify ferns and better understand their ecological roles. This knowledge is particularly useful for conservation efforts, as it aids in monitoring and protecting fern populations in their natural habitats.

For those interested in cultivating ferns, encouraging sporangia formation can be a rewarding endeavor. Providing optimal growing conditions—such as consistent moisture, indirect light, and well-draining soil—can promote healthy spore development. However, it’s important to avoid overwatering, as excessive moisture can lead to fungal diseases that damage sporangia. Additionally, ferns thrive in humid environments, so misting the leaves or using a humidity tray can support their reproductive processes. By fostering these conditions, gardeners can witness the fascinating lifecycle of ferns firsthand.

In conclusion, sporangia formation is a critical aspect of fern reproduction, showcasing the plant’s adaptability and resilience. Whether observed in the wild or cultivated at home, understanding this process enriches our appreciation of ferns and their ecological significance. By recognizing the role of sporangia, we can better care for these ancient plants and ensure their continued existence in diverse ecosystems.

Can Lysol Spray Effectively Eliminate Airborne Mold Spores in Your Home?

You may want to see also

Spores Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, and animals aid in spreading fern spores widely

Ferns, unlike flowering plants, rely on spores for reproduction, and the success of this process hinges on effective dispersal. Wind, water, and animals each play distinct roles in carrying these microscopic spores to new habitats, ensuring the species' survival and propagation. Wind, the most common agent, whisks spores away from the parent plant, often over vast distances. Ferns have evolved lightweight, dust-like spores that can remain airborne for extended periods, increasing the likelihood of landing in a suitable environment. For instance, the spores of the Bracken fern (*Pteridium aquilinum*) can travel several kilometers, aided by their minuscule size and the wind's unpredictability.

Water, though less universal than wind, is a crucial dispersal method for ferns in aquatic or humid environments. Spores released near water bodies can be carried downstream, colonizing new areas along riverbanks or damp soil. The Water Fern (*Azolla*) exemplifies this strategy, as its spores are often dispersed by surface tension and gentle currents. This method is particularly effective in tropical and subtropical regions where water is abundant and flows consistently. However, reliance on water limits dispersal to specific ecosystems, making it a niche but vital mechanism.

Animals, often overlooked in spore dispersal, contribute significantly through indirect means. Small creatures like insects, birds, or mammals may inadvertently carry spores on their bodies or fur as they move through fern-rich areas. For example, a beetle crawling on a fern frond can pick up spores and deposit them elsewhere while foraging. Similarly, birds nesting in ferns may transport spores to new locations. While less efficient than wind or water, animal-mediated dispersal introduces an element of randomness, allowing ferns to reach otherwise inaccessible areas.

Understanding these dispersal methods highlights the adaptability of ferns in propagating their species. Wind maximizes reach, water ensures localized spread in moist habitats, and animals provide opportunistic dispersal. Gardeners and conservationists can leverage this knowledge to cultivate ferns effectively. For instance, planting ferns near water features or in open, breezy areas can enhance spore dispersal. Additionally, creating habitats that attract small animals can indirectly support fern propagation. By mimicking natural conditions, humans can aid in the survival of these ancient plants, ensuring their continued presence in diverse ecosystems.

Optimal Timing for Planting Morel Spores: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Germination Process: Spores grow into gametophytes, the sexual stage of ferns

Ferns, unlike flowering plants, rely on spores for reproduction, a process that begins with the germination of these microscopic units. When a spore lands in a suitable environment—typically moist and shaded—it absorbs water and initiates growth. This marks the beginning of the gametophyte stage, a critical and often overlooked phase in the fern life cycle. The gametophyte is a small, heart-shaped structure that develops from the spore and serves as the sexual stage of the fern’s life cycle. It is here that the fern’s reproductive organs, the antheridia (male) and archegonia (female), form, setting the stage for fertilization.

The germination process is highly sensitive to environmental conditions. Spores require consistent moisture to activate and sustain growth, as they lack the protective outer layers found in seeds. Optimal temperature ranges for germination vary by species but generally fall between 15°C and 25°C (59°F to 77°F). Light exposure also plays a role; while some fern spores require light to trigger germination, others may germinate in darkness. Gardeners and botanists should mimic these conditions when cultivating ferns from spores, using a sterile medium like peat moss or vermiculite and maintaining high humidity with a plastic dome or misting.

Once the gametophyte emerges, it becomes the site of sexual reproduction. Sperm from the antheridia swim through a thin film of water to reach the egg in the archegonium, a process dependent on moisture. This fertilization results in the formation of a new fern plant, known as the sporophyte. The gametophyte, though short-lived, is essential for bridging the gap between spore and mature fern. Its success hinges on the availability of water, as desiccation can halt reproduction before it begins.

Comparatively, the gametophyte stage in ferns is far more independent than in other plant groups like mosses, where the gametophyte is the dominant generation. In ferns, the sporophyte (the familiar leafy plant) is the dominant stage, while the gametophyte is diminutive and transient. This distinction highlights the unique balance ferns strike in their life cycle, blending reliance on both generations. Understanding this process not only sheds light on fern biology but also aids in conservation efforts, as habitat disruption can severely impact spore germination and gametophyte survival.

Practical tips for observing this process include collecting spores from mature fern fronds in late summer and sowing them on a damp substrate in a shaded area. Patience is key, as gametophytes may take weeks to develop. For educational purposes, placing the substrate in a clear container allows for easy monitoring without disturbing the delicate structures. By studying the germination of spores into gametophytes, enthusiasts gain insight into the intricate reproductive strategies of ferns, a testament to their resilience and adaptability in diverse ecosystems.

Mastering Spore Modding: A Step-by-Step Guide to Custom Creations

You may want to see also

Environmental Factors: Humidity, light, and temperature influence spore production and viability

Ferns, unlike flowering plants, rely on spores for reproduction, and the success of this process is intricately tied to environmental conditions. Humidity, for instance, plays a pivotal role in spore development and dispersal. Ferns thrive in moist environments, and relative humidity levels above 50% are ideal for sporophyte maturation. In regions with humidity below 40%, spore production often declines, and viability decreases due to desiccation. To optimize spore production in controlled settings, such as greenhouses, maintaining humidity between 60-70% is recommended. Misting systems or humidity trays can be employed to achieve this, ensuring the fronds remain adequately moist without becoming waterlogged.

Light, another critical factor, influences both the quantity and quality of spores. Ferns generally prefer indirect, filtered light, as direct sunlight can scorch their delicate fronds. Studies show that sporophytes exposed to 10-15 klux (a measure of light intensity) produce more viable spores compared to those in lower light conditions. However, excessive light can inhibit spore germination, making it essential to strike a balance. For indoor cultivation, placing ferns near north-facing windows or using sheer curtains to diffuse sunlight can mimic their natural habitat. Outdoor ferns benefit from dappled shade, such as that provided by taller trees or lattice structures.

Temperature acts as a silent regulator of spore production, with ferns exhibiting specific thermal preferences. Most species perform optimally within a temperature range of 18-24°C (64-75°F). Temperatures below 15°C can slow sporophyte development, while those above 30°C may halt it entirely. Seasonal fluctuations also play a role; many ferns synchronize spore release with cooler, wetter seasons to maximize dispersal efficiency. For hobbyists, using thermostats or placing ferns away from heat sources can help maintain ideal conditions. In colder climates, insulating outdoor ferns with mulch or burlap during winter can protect them from freezing temperatures that could damage developing spores.

The interplay of these environmental factors underscores the delicate balance required for successful fern reproduction. For example, high humidity without adequate light can lead to mold growth, while optimal temperature without sufficient moisture renders spores nonviable. A holistic approach, considering all three factors, is essential for both conservation efforts and cultivation. Monitoring environmental conditions with tools like hygrometers and thermometers can provide valuable data, allowing adjustments to be made in real time. By understanding and manipulating these variables, enthusiasts and researchers alike can enhance spore production and ensure the longevity of these ancient plants.

Understanding Milky Spore: A Natural Grub Control Solution for Lawns

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, ferns produce spores as part of their reproductive cycle.

Ferns produce spores in structures called sporangia, which are typically located on the undersides of their fronds.

Fern spores serve as the means of asexual reproduction, allowing ferns to disperse and grow in new locations.

Fern spores are found in clusters called sori, which are usually located on the undersides of mature fern leaves (fronds).