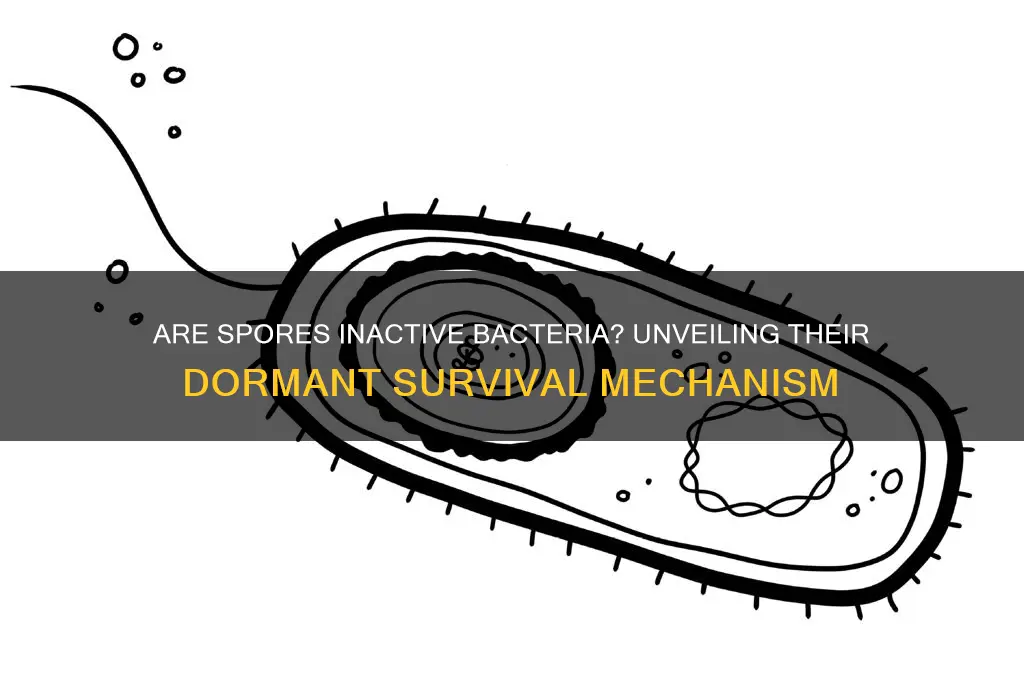

Spores are often misunderstood as inactive forms of bacteria, but they are, in fact, highly specialized, dormant structures produced by certain bacteria, fungi, and plants as a survival mechanism. Unlike vegetative bacterial cells, spores are metabolically inactive and possess a robust, protective outer layer that enables them to withstand extreme environmental conditions such as heat, desiccation, and radiation. This dormancy allows spores to remain viable for extended periods, sometimes even centuries, until favorable conditions return, at which point they can germinate and resume active growth. While spores are not inactive in the sense of being lifeless, their metabolic inactivity and resilience make them a unique and fascinating adaptation in the microbial world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

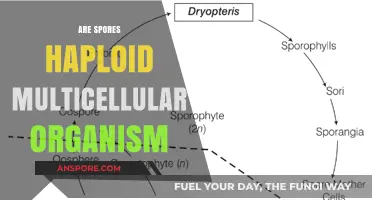

| Definition | Spores are highly resistant, dormant structures produced by certain bacteria (primarily Gram-positive bacteria like Bacillus and Clostridium) and some fungi. |

| Activity | Spores are metabolically inactive and do not grow or reproduce under normal conditions. |

| Purpose | Serve as a survival mechanism to withstand harsh environmental conditions (e.g., heat, desiccation, chemicals). |

| Structure | Consist of a core containing DNA, surrounded by protective layers (spore coat, cortex, and sometimes an exosporium). |

| Resistance | Highly resistant to radiation, extreme temperatures, and disinfectants. |

| Germination | Can revert to active bacterial cells (vegetative form) under favorable conditions (e.g., nutrients, moisture). |

| Metabolism | Minimal to no metabolic activity in spore form. |

| Reproduction | Spores do not reproduce; they germinate into vegetative cells that can then reproduce. |

| Examples | Bacillus anthracis (causes anthrax), Clostridium botulinum (causes botulism). |

| Significance | Important in food spoilage, sterilization processes, and medical/biological research. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation Process: Bacteria form spores under stress, a protective mechanism for survival in harsh conditions

- Dormancy vs. Inactivity: Spores are dormant, not inactive; they can revive under favorable conditions

- Resistance Mechanisms: Spores resist heat, radiation, and chemicals, ensuring bacterial survival in extreme environments

- Germination Triggers: Nutrients, moisture, and warmth activate spores, initiating bacterial growth and replication

- Medical and Industrial Impact: Spores pose challenges in sterilization and contribute to food spoilage and infections

Spore Formation Process: Bacteria form spores under stress, a protective mechanism for survival in harsh conditions

Bacteria, when faced with adverse environmental conditions such as nutrient depletion, extreme temperatures, or desiccation, initiate a remarkable survival strategy: spore formation. This process, known as sporulation, transforms the bacterium into a highly resilient, dormant state. Unlike the vegetative form, which is metabolically active and vulnerable, spores are characterized by their ability to withstand harsh conditions for extended periods. The key to this resilience lies in the spore’s robust structure, which includes multiple protective layers, low water content, and DNA repair mechanisms. Understanding this process not only sheds light on bacterial survival but also has practical implications in fields like food preservation, medicine, and environmental science.

The spore formation process begins with an asymmetric cell division, where the bacterium divides into a larger mother cell and a smaller forespore. This division is triggered by stress signals, such as the absence of essential nutrients like carbon or nitrogen. The mother cell then engulfs the forespore, providing it with additional layers of protection. One of the most critical layers is the cortex, composed of peptidoglycan, which dehydrates the spore’s interior, further enhancing its durability. Surrounding the cortex is the coat, a proteinaceous layer that acts as a barrier against enzymes, chemicals, and physical damage. In some bacteria, like *Bacillus anthracis*, an exosporium layer is also present, offering additional protection and aiding in environmental attachment.

While spores are often described as "inactive," this term can be misleading. Spores are not dead or completely metabolically inert; rather, they exist in a state of suspended animation. Their metabolic activity is drastically reduced, but they retain the ability to sense environmental changes. For instance, spores can detect nutrients like amino acids or sugars, which trigger germination—the process of reverting to the vegetative, active form. This ability to remain viable for years, even centuries, under extreme conditions underscores the spore’s role as a survival mechanism rather than a state of inactivity.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore formation is crucial for industries that combat bacterial contamination. For example, in food processing, spores of *Clostridium botulinum* and *Bacillus cereus* pose significant risks due to their heat resistance. Traditional pasteurization (72°C for 15 seconds) may not eliminate these spores, necessitating more aggressive methods like sterilization (121°C for 15 minutes). Similarly, in healthcare, spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridioides difficile* are notorious for causing hospital-acquired infections, often surviving routine disinfection protocols. Effective strategies to control spore-forming bacteria include combining heat treatment with chemical agents like hydrogen peroxide or peracetic acid, which can penetrate the spore’s protective layers.

In conclusion, spore formation is a sophisticated bacterial response to stress, enabling survival in environments that would otherwise be lethal. While spores are often termed "inactive," they are better described as dormant yet highly resilient. This distinction is critical for developing strategies to control or utilize spore-forming bacteria. Whether in preserving food, treating infections, or studying microbial ecology, recognizing the unique characteristics of spores allows for more targeted and effective interventions. By unraveling the intricacies of sporulation, we gain insights into one of nature’s most ingenious survival mechanisms.

Why Do Bacteria Form Spores: Survival Strategies in Harsh Environments

You may want to see also

Dormancy vs. Inactivity: Spores are dormant, not inactive; they can revive under favorable conditions

Spores are often mistaken for inactive forms of bacteria, but this misconception overlooks a critical distinction: dormancy versus inactivity. While inactive implies a complete cessation of metabolic processes, dormant spores maintain a state of suspended animation, ready to spring back to life when conditions improve. This subtle difference is key to understanding their survival strategy. For instance, bacterial spores like those of *Bacillus anthracis* (the causative agent of anthrax) can remain dormant in soil for decades, enduring extreme temperatures, desiccation, and radiation, only to revive when nutrients become available.

To illustrate the concept further, consider the process of sporulation in *Bacillus subtilis*, a model organism for studying bacterial dormancy. When nutrients deplete, this bacterium undergoes a series of genetic and structural changes, culminating in the formation of a spore encased in a protective coat. This spore is not inactive; it continues to perform minimal metabolic activities, such as DNA repair, ensuring its viability. The revival process, known as germination, is triggered by specific stimuli like warmth, moisture, and nutrients, demonstrating that dormancy is a strategic pause, not a permanent shutdown.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this distinction has significant implications, particularly in fields like food safety and medicine. For example, food preservation methods like pasteurization are designed to kill vegetative bacteria but are often ineffective against spores. This is why canned foods must be heated to 121°C (250°F) for at least 15 minutes to ensure spore destruction. Similarly, in healthcare, antibiotic treatments may fail if they target only active bacteria, leaving dormant spores to later revive and cause recurrent infections. Recognizing that spores are dormant, not inactive, underscores the need for targeted strategies to combat them.

A comparative analysis highlights the evolutionary advantage of dormancy over inactivity. While inactive forms would require energy to "reboot" their systems, dormant spores are pre-programmed to revive efficiently. This efficiency is evident in the rapid germination of *Clostridium botulinum* spores in improperly canned foods, leading to botulism. In contrast, truly inactive organisms would face greater challenges in resuming life, making dormancy a more adaptive survival mechanism. This distinction also explains why spores are found in extreme environments, from the Arctic permafrost to hot springs, where they await the right conditions to thrive.

In conclusion, the confusion between dormancy and inactivity in spores stems from an oversimplification of their biology. Spores are not lifeless relics but resilient survivors, poised to revive under favorable conditions. This understanding is crucial for developing effective strategies to control them, whether in preserving food, treating infections, or studying microbial life in extreme environments. By recognizing their dormant nature, we can better appreciate the sophistication of bacterial survival mechanisms and tailor our approaches accordingly.

Mastering Psilocybe Cubensis Cultivation: A Step-by-Step Spores Guide

You may want to see also

Resistance Mechanisms: Spores resist heat, radiation, and chemicals, ensuring bacterial survival in extreme environments

Spores, often referred to as the "survival pods" of bacteria, are not merely dormant entities but highly specialized structures engineered to withstand extreme conditions. Their resistance to heat, radiation, and chemicals is a testament to the ingenuity of microbial survival strategies. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores can endure temperatures exceeding 100°C for hours, a feat achieved through a robust protein coat and a dehydrated core that minimizes molecular damage. This resilience is not passive but an active adaptation, allowing bacteria to persist in environments where most life forms would perish.

To understand how spores resist such harsh conditions, consider their structural design. The spore’s outer layers, including the exosporium and coat proteins, act as a protective shield against chemicals and radiation. Internally, the core’s low water content and DNA-protecting proteins like SASP (Small Acid-Soluble Proteins) prevent DNA damage from heat and radiation. For example, exposure to UV radiation or gamma rays, which typically disrupt DNA replication, is neutralized by these mechanisms, ensuring the spore’s genetic material remains intact. Practical applications of this knowledge include sterilizing medical equipment, where autoclaves use steam at 121°C for 15–20 minutes to kill spores, a process critical in preventing infections.

From a comparative perspective, spores’ resistance mechanisms outshine those of vegetative bacterial cells. While a typical *E. coli* cell might survive brief exposure to 60°C, spores of *Clostridium botulinum* can withstand pasteurization temperatures (72°C for 15 seconds) and even some industrial sterilization processes. This disparity highlights the spore’s evolutionary advantage in extreme environments, such as soil, hot springs, or even outer space. NASA studies have shown that bacterial spores can survive years in space, shielded from cosmic radiation by their intricate layers, raising questions about interplanetary contamination.

For those working in industries like food preservation or healthcare, understanding spore resistance is crucial. Chemicals like hydrogen peroxide (3–6% concentration) or ethanol (70%) are commonly used disinfectants, but spores often require higher concentrations or longer exposure times to be eradicated. A practical tip: when cleaning surfaces potentially contaminated with spore-forming bacteria, use a two-step approach—first, remove organic matter, then apply a sporicide like bleach (5% sodium hypochlorite) for at least 10 minutes. This ensures that even the hardiest spores are neutralized, reducing the risk of outbreaks like *Clostridium difficile* infections in hospitals.

In conclusion, spores’ resistance to heat, radiation, and chemicals is not just a biological curiosity but a critical factor in fields ranging from public health to astrobiology. Their ability to remain viable for decades, if not centuries, underscores the importance of targeted strategies to combat them. Whether in a laboratory, kitchen, or spacecraft, recognizing and addressing spore resilience is essential for ensuring safety and preventing microbial persistence in the most unforgiving environments.

Dandelion Puffballs: Unveiling the Truth About Their Spores and Seeds

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$12.98 $13.98

Germination Triggers: Nutrients, moisture, and warmth activate spores, initiating bacterial growth and replication

Spores, often described as dormant survival structures, are not entirely inactive but rather exist in a state of suspended animation. This metabolic slowdown allows them to withstand harsh conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, and chemical exposure. However, their resilience is not permanent; under the right conditions, spores can revert to active bacterial cells, a process known as germination. This transformation is not spontaneous but requires specific triggers: nutrients, moisture, and warmth. These factors act as signals, informing the spore that the environment is now conducive to growth and replication.

Consider the role of nutrients in this process. Spores are metabolically inactive and lack the energy to initiate germination on their own. When nutrients such as amino acids, sugars, or salts become available, they bind to specific receptors on the spore’s surface, triggering a cascade of biochemical reactions. For example, in *Bacillus subtilis*, the presence of L-valine or a combination of L-alanine and purine nucleosides is essential for germination. Without these specific nutrients, spores remain dormant, even if other conditions are favorable. This specificity ensures that spores only activate when resources are sufficient to support subsequent bacterial growth.

Moisture is another critical factor. While spores can survive in dry environments for years, they require water to rehydrate and resume metabolic activity. Water molecules penetrate the spore’s protective coat, rehydrating its core and enabling enzymatic activity. For instance, studies show that *Clostridium botulinum* spores require a water activity (aw) of at least 0.94 to germinate effectively. In practical terms, this means that controlling humidity levels in food storage can prevent spore germination, reducing the risk of bacterial contamination. Proper drying techniques, such as those used in canning or freeze-drying, exploit this requirement by depriving spores of the moisture they need to activate.

Warmth acts as the final catalyst, accelerating the germination process. Most bacterial spores have an optimal germination temperature range, typically between 25°C and 40°C, depending on the species. For example, *Bacillus cereus* spores germinate most efficiently at 30°C, while *Clostridium perfringens* prefers temperatures around 43°C. This temperature sensitivity is why refrigeration (4°C) and freezing (-18°C) are effective food preservation methods—they slow metabolic activity and inhibit germination. Conversely, heat treatments, such as pasteurization (63°C for 30 minutes) or sterilization (121°C for 15 minutes), can kill both spores and vegetative cells, ensuring food safety.

Understanding these germination triggers has practical applications in fields like food safety, medicine, and environmental science. For instance, in the food industry, controlling nutrient availability, moisture levels, and temperature during processing and storage can prevent spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridium* and *Bacillus* from causing spoilage or illness. In healthcare, knowing that spores require warmth and nutrients to activate helps in designing sterilization protocols for medical equipment. By manipulating these environmental factors, we can effectively manage bacterial growth, ensuring safety and extending the shelf life of products. This knowledge underscores the importance of precision in controlling conditions to keep spores in their dormant state, where they pose no immediate threat.

Ringworm Spores: Are They Lurking Everywhere in Your Environment?

You may want to see also

Medical and Industrial Impact: Spores pose challenges in sterilization and contribute to food spoilage and infections

Spores, often described as dormant forms of bacteria, are remarkably resilient structures that can withstand extreme conditions, including heat, radiation, and chemicals. This resilience poses significant challenges in medical and industrial settings, particularly in sterilization processes. For instance, in healthcare, spores of bacteria like *Clostridium difficile* and *Bacillus anthracis* can survive standard disinfection methods, leading to persistent infections in hospitals. Similarly, in the food industry, spores of *Bacillus cereus* and *Clostridium botulinum* can endure pasteurization and cooking temperatures, causing food spoilage and foodborne illnesses. Understanding the mechanisms behind spore resistance is crucial for developing effective sterilization techniques and ensuring safety in both medical and industrial applications.

In medical environments, the presence of spores complicates sterilization protocols, especially in surgical instruments and pharmaceutical production. Autoclaves, commonly used to sterilize equipment, operate at 121°C and 15 psi for 15–30 minutes, which is effective against most microorganisms but not all spores. For example, *Geobacillus stearothermophilus* spores are frequently used as biological indicators to test autoclave efficiency because of their high resistance. To address this, industries often employ additional methods such as chemical sterilants like hydrogen peroxide or ethylene oxide, which penetrate spore coats more effectively. However, these methods require precise application and can be hazardous if not handled correctly, emphasizing the need for rigorous training and monitoring.

The food industry faces similar challenges, as spores can survive processing conditions designed to eliminate vegetative bacteria. For instance, canned foods undergo thermal processing, but if spores are not completely destroyed, they can germinate and spoil the product. This is particularly concerning with *Clostridium botulinum*, which produces a potent toxin in anaerobic conditions. To mitigate this risk, manufacturers often use a combination of heat treatment (e.g., 121°C for 3 minutes) and preservatives like sodium benzoate or nitrites. Consumers can also play a role by following storage instructions, such as refrigerating canned goods once opened and avoiding consuming bulging or leaking containers, which may indicate spore germination.

From a comparative perspective, the industrial impact of spores extends beyond healthcare and food into fields like biotechnology and agriculture. In biotechnology, spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus subtilis* are used for producing enzymes and probiotics, but their resilience can complicate fermentation processes. In agriculture, spores of pathogens like *Bacillus anthracis* (causative agent of anthrax) pose risks to livestock and humans, requiring stringent biosecurity measures. While these applications highlight the dual nature of spores—both beneficial and harmful—they underscore the importance of targeted strategies to manage their presence. For example, using spore-specific bacteriophages or antimicrobial peptides could offer precise control without disrupting beneficial microbial communities.

Finally, addressing the challenges posed by spores requires a multidisciplinary approach, combining scientific research, technological innovation, and practical guidelines. Researchers are exploring novel methods such as cold plasma treatment and nanomaterial-based coatings to enhance spore inactivation. Industries must adopt these advancements while adhering to regulatory standards, such as those set by the FDA or WHO. For individuals, awareness of spore risks—whether in handling contaminated food or using medical devices—can prevent infections and spoilage. By integrating knowledge, technology, and vigilance, we can minimize the impact of spores and ensure safety across medical and industrial domains.

Unveiling the Truth: Does Moss Have Spores and How Do They Spread?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, spores are dormant, inactive forms of bacteria that are highly resistant to harsh environmental conditions.

Yes, bacterial spores can survive extreme temperatures, including boiling water and freezing conditions, due to their protective outer layer.

No, spores have minimal to no metabolic activity, which allows them to remain viable for extended periods without nutrients or favorable conditions.

Spores differ from vegetative bacterial cells in that they are non-reproductive, highly resistant, and inactive, whereas vegetative cells are metabolically active and capable of growth and reproduction.

Yes, under favorable conditions, spores can germinate and revert back to their active, vegetative bacterial form, resuming growth and metabolic activity.