Spores are reproductive structures produced by various organisms, including plants, fungi, and some bacteria, and their mode of reproduction can be either sexual or asexual, depending on the species and environmental conditions. In asexual reproduction, spores are typically formed through mitosis, resulting in genetically identical offspring, while in sexual reproduction, spores are often the product of meiosis and fertilization, leading to genetic diversity. For instance, fungal spores can be asexual, such as conidia, or sexual, like asci and basidiospores, whereas plant spores, like those of ferns and mosses, are usually the result of alternation of generations, involving both sexual and asexual phases. Understanding whether spores are sexual or asexual is crucial for comprehending the life cycles and evolutionary strategies of the organisms that produce them.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Nature of Spores | Spores can be either sexual or asexual, depending on their origin and function. |

| Asexual Spores | Produced by mitosis (e.g., conidia in fungi, spores in bacteria like endospores). Do not involve genetic recombination. Serve for asexual reproduction and survival in harsh conditions. |

| Sexual Spores | Produced by meiosis (e.g., zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores in fungi). Involve genetic recombination through fusion of gametes. Result from sexual reproduction. |

| Genetic Diversity | Asexual spores maintain genetic identity of parent. Sexual spores introduce genetic variation through recombination. |

| Function | Asexual spores primarily for dispersal and survival. Sexual spores for reproduction and long-term adaptation. |

| Examples | Asexual: Bacterial endospores, fungal conidia. Sexual: Fungal zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores. |

| Formation Process | Asexual: Single parent, no gamete fusion. Sexual: Involves fusion of gametes (e.g., hyphae in fungi). |

| Role in Life Cycle | Asexual spores part of vegetative phase. Sexual spores part of reproductive phase. |

| Resistance | Both types can be resistant to harsh conditions, but asexual spores often more resilient (e.g., bacterial endospores). |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Both used for dispersal, but asexual spores more common for rapid colonization. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation Processes: Asexual spores form via mitosis; sexual spores result from meiosis and fertilization

- Types of Spores: Asexual (e.g., conidia) vs. sexual (e.g., zygospores, ascospores)

- Fungal Reproduction Methods: Asexual via spores (vegetative) or sexual (involving gametes)

- Plant Spores: Alternation of generations includes both asexual (sporophyte) and sexual (gametophyte)

- Bacterial Spores: Endospores are asexual, formed for survival, not reproduction

Spore Formation Processes: Asexual spores form via mitosis; sexual spores result from meiosis and fertilization

Spores, the microscopic units of life, are nature's ingenious solution for survival and dispersal. Their formation processes, however, are not one-size-fits-all. Asexual spores, for instance, are the product of mitosis, a cellular division process that results in genetically identical offspring. This method ensures rapid reproduction and colonization, making it ideal for fungi like molds and yeasts. Imagine a single mold spore landing on a damp surface—within hours, it can divide and form a visible colony, all without the need for a partner. This asexual approach is efficient but lacks genetic diversity, which can be a double-edged sword in changing environments.

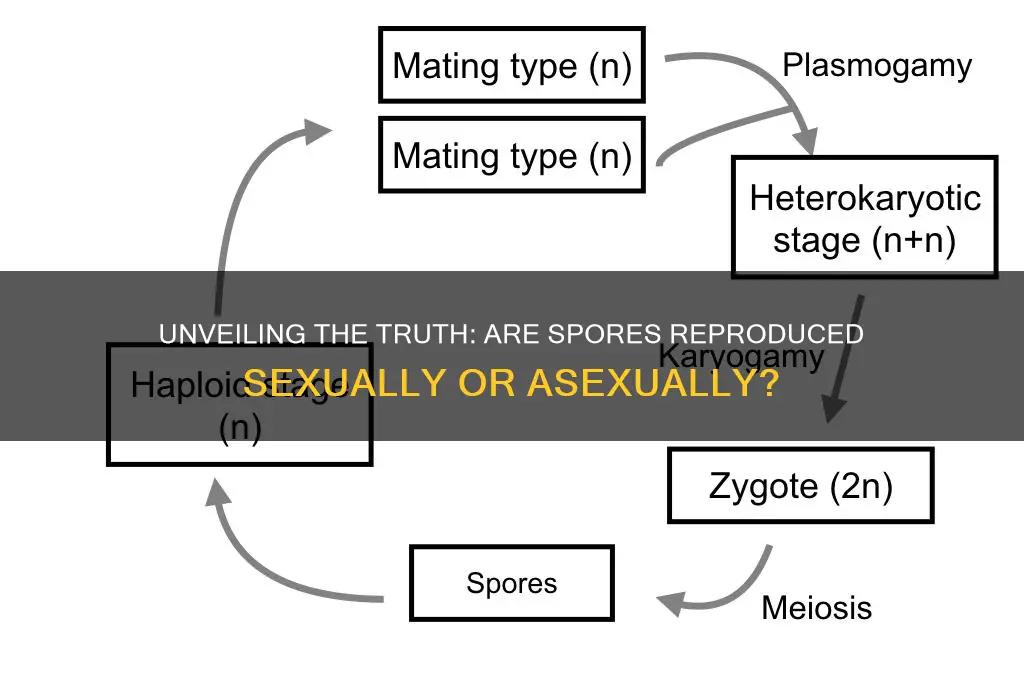

Contrastingly, sexual spores emerge from a more intricate dance: meiosis and fertilization. Meiosis, a type of cell division, reduces the chromosome number by half, creating haploid cells. These cells then fuse during fertilization, restoring the full chromosome set but with a unique genetic combination. This process is seen in organisms like ferns and some fungi, where gametangia (specialized structures) produce gametes that unite to form zygotes. The resulting spores are genetically diverse, enhancing adaptability. For example, fern spores can survive harsh conditions and germinate when favorable, a survival strategy honed over millennia.

The distinction between these processes is not just academic—it has practical implications. In agriculture, understanding spore formation helps combat fungal diseases. Asexual spores, like those of *Botrytis cinerea* (gray mold), can be managed by disrupting their mitotic cycle with fungicides. Sexual spores, however, require a different approach, as their genetic variability can lead to resistance. For instance, *Fusarium* species, which produce sexual spores, often develop resistance to azole fungicides, necessitating integrated pest management strategies.

From a biological perspective, the choice between asexual and sexual spore formation reflects an organism's evolutionary priorities. Asexual reproduction prioritizes speed and efficiency, while sexual reproduction invests in long-term survival through diversity. Consider the baker's yeast *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, which primarily reproduces asexually but switches to sexual reproduction under stress, forming asci (spore-containing structures) to endure adverse conditions. This dual strategy showcases the flexibility of spore formation in response to environmental cues.

In practical terms, knowing whether spores are sexual or asexual can guide interventions in fields like medicine and conservation. For instance, *Aspergillus fumigatus*, a fungus producing asexual spores (conidia), is a common cause of infections in immunocompromised individuals. Targeting its mitotic process could inhibit its spread. Conversely, understanding the sexual cycle of *Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis*, a chytrid fungus threatening amphibians, could lead to strategies that disrupt its spore formation, aiding conservation efforts. By dissecting these processes, we unlock tools to manipulate spore behavior for human and ecological benefit.

Stun Spore vs. Electric Types: Does It Work in Pokémon Battles?

You may want to see also

Types of Spores: Asexual (e.g., conidia) vs. sexual (e.g., zygospores, ascospores)

Spores are microscopic, resilient structures produced by various organisms, primarily fungi, plants, and some bacteria, to survive harsh conditions and disperse. They can be broadly categorized into asexual and sexual spores, each serving distinct purposes in the life cycles of their producers. Asexual spores, such as conidia, are formed through mitosis and are genetically identical to the parent organism. In contrast, sexual spores, like zygospores and ascospores, result from meiosis and genetic recombination, introducing diversity. Understanding these differences is crucial for fields like agriculture, medicine, and ecology, where spore behavior impacts disease spread, plant reproduction, and ecosystem dynamics.

Asexual spores, exemplified by conidia in fungi like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*, are produced rapidly and in large quantities. They are a primary means of dispersal and survival in favorable conditions. Conidia are often airborne, allowing fungi to colonize new environments quickly. For instance, in agriculture, conidia of *Botrytis cinerea* cause gray mold on fruits and vegetables, highlighting their role in plant pathogens. However, their asexual nature limits genetic variation, making them vulnerable to environmental changes or targeted fungicides. To manage conidia-producing fungi, farmers can employ cultural practices like crop rotation and fungicides with specific active ingredients, such as boscalid or pyraclostrobin, applied at recommended dosages (e.g., 0.5–1.0 L/ha for boscalid).

Sexual spores, on the other hand, are formed through the fusion of gametes, a process that introduces genetic diversity. Zygospores, produced by fungi like *Mucor* and *Rhizopus*, are thick-walled and highly resistant to extreme conditions, enabling long-term survival in soil or decaying matter. Ascospores, found in sac fungi (Ascomycota), are released from ascus structures and play a key role in diseases like powdery mildew in grapes. For example, *Erysiphe necator*, the causative agent of grape powdery mildew, disperses ascospores in spring, necessitating early-season fungicide applications (e.g., sulfur or tebuconazole at 0.5–1.0 kg/ha). This genetic diversity in sexual spores enhances adaptability, making them more challenging to control compared to asexual spores.

Comparing the two types reveals their ecological and practical implications. Asexual spores dominate in environments favoring rapid colonization, while sexual spores are critical for long-term survival and adaptation. For instance, in mycology, understanding spore type helps predict fungal behavior in different conditions. In medicine, asexual spores of *Aspergillus fumigatus* cause invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised individuals, whereas sexual spores are rare but contribute to genetic variability in fungal pathogens. Researchers and practitioners can leverage this knowledge to develop targeted strategies, such as using spore traps to monitor airborne conidia levels in hospitals or applying fungicides at specific developmental stages of sexual spore-producing fungi.

In conclusion, the distinction between asexual and sexual spores is fundamental to their function and management. Asexual spores like conidia offer rapid proliferation but limited genetic diversity, while sexual spores like zygospores and ascospores ensure survival and adaptability. Practical applications, from agriculture to medicine, rely on this understanding to mitigate risks and optimize outcomes. By recognizing the unique characteristics of each spore type, stakeholders can implement informed strategies, whether controlling fungal diseases in crops or preventing spore-related infections in clinical settings.

Mastering Psilocybe Cubensis Cultivation: A Step-by-Step Spores Guide

You may want to see also

Fungal Reproduction Methods: Asexual via spores (vegetative) or sexual (involving gametes)

Fungi, a diverse kingdom of organisms, employ a range of reproductive strategies to ensure their survival and proliferation. At the heart of this diversity lies a fundamental distinction: asexual reproduction via spores (vegetative) versus sexual reproduction involving gametes. Understanding these methods is crucial for fields like mycology, agriculture, and medicine, as it sheds light on fungal life cycles, disease spread, and ecological roles.

Spores, often misunderstood as exclusively asexual, are actually versatile structures that can serve both asexual and sexual purposes. Asexual spores, such as conidia and chlamydospores, are produced through mitosis and are genetically identical to the parent fungus. These spores are akin to clones, allowing for rapid colonization of favorable environments. For instance, the mold *Aspergillus* produces conidia that disperse through air, enabling it to thrive in diverse habitats, from soil to food storage areas. This asexual method is efficient for stable environments but lacks genetic diversity, making it less adaptable to changing conditions.

Sexual reproduction in fungi, on the other hand, involves the fusion of gametes, typically from two compatible individuals, leading to the formation of sexual spores like asci or basidiospores. This process, known as karyogamy, results in genetic recombination, producing offspring with new combinations of traits. For example, the mushroom *Coprinus cinereus* undergoes sexual reproduction by forming basidia, which release basidiospores capable of surviving harsh conditions. This genetic diversity is a survival advantage, equipping fungal populations to withstand diseases, environmental stresses, and predators.

The choice between asexual and sexual reproduction often depends on environmental cues. In nutrient-rich, stable conditions, fungi favor asexual reproduction for its speed and efficiency. However, in stressful or unpredictable environments, sexual reproduction becomes more prevalent, as it generates the genetic variability needed for adaptation. For instance, the fungus *Neurospora crassa* switches to sexual reproduction when nutrients are scarce, ensuring its long-term survival.

Practical applications of understanding these methods are vast. In agriculture, managing fungal pathogens like *Botrytis cinerea* (gray mold) requires disrupting their asexual spore production to prevent rapid spread. Conversely, promoting sexual reproduction in beneficial fungi, such as mycorrhizal species, can enhance soil health and plant growth. For hobbyists cultivating mushrooms, controlling humidity and temperature can encourage the formation of sexual spores, leading to more robust fruiting bodies.

In conclusion, fungal reproduction methods—asexual via spores or sexual via gametes—are not mutually exclusive but complementary strategies. Asexual reproduction ensures rapid proliferation, while sexual reproduction fosters genetic diversity and resilience. By studying these mechanisms, we gain insights into fungal ecology and develop strategies to harness their benefits or mitigate their harms. Whether in a laboratory, farm, or forest, understanding these reproductive pathways is key to interacting effectively with the fungal kingdom.

Unveiling the Fascinating Process of How Spores Are Created

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$3.99

$9.99

Plant Spores: Alternation of generations includes both asexual (sporophyte) and sexual (gametophyte)

Spores in plants are not exclusively sexual or asexual; they are part of a complex life cycle known as alternation of generations, where both phases play distinct roles. In this cycle, the sporophyte generation produces spores asexually through meiosis, while the gametophyte generation produces gametes (sperm and eggs) sexually through fertilization. This dual system ensures genetic diversity and adaptability in plant species. For instance, ferns exhibit this clearly: the large, visible fern plant is the sporophyte, which releases spores that grow into small, heart-shaped gametophytes. These gametophytes then produce gametes, completing the cycle.

To understand this process, consider the steps involved in alternation of generations. First, the sporophyte plant matures and develops sporangia, structures that produce spores via meiosis. These spores are haploid, meaning they contain half the genetic material of the parent plant. When a spore germinates, it grows into a gametophyte, which is also haploid. The gametophyte then produces gametes—sperm and eggs—through mitosis. Fertilization occurs when a sperm from one gametophyte fuses with an egg from another, forming a diploid zygote. This zygote develops into a new sporophyte, restarting the cycle. This alternation ensures both asexual and sexual reproduction are integral to the plant’s life cycle.

A key takeaway is that spores themselves are asexual in origin, produced by the sporophyte without fertilization. However, their role in the life cycle is to give rise to the gametophyte, which engages in sexual reproduction. This distinction is crucial for gardeners, botanists, and educators. For example, when propagating ferns, understanding that spores develop into gametophytes—which require specific conditions like moisture and shade—can improve success rates. Similarly, in agriculture, recognizing the alternation of generations in crops like wheat (which lacks a dominant gametophyte phase) versus algae (where both phases are prominent) can inform cultivation practices.

Comparatively, this system contrasts with organisms that rely solely on asexual or sexual reproduction. Asexual reproducers, like bacteria, clone themselves, limiting genetic diversity. Sexual reproducers, like mammals, depend entirely on gamete fusion, which introduces variation but requires a mate. Plants, however, leverage both strategies through alternation of generations. This hybrid approach allows them to thrive in diverse environments, from arid deserts to dense forests. For instance, mosses have a dominant gametophyte phase, while seed plants like pines have a dominant sporophyte phase, showcasing the flexibility of this system.

In practical terms, understanding alternation of generations can enhance plant conservation and horticulture. For example, in restoring endangered plant species, knowing whether the gametophyte or sporophyte phase is more vulnerable can guide interventions. Additionally, in breeding programs, manipulating the life cycle stages can accelerate the development of desirable traits. For hobbyists, recognizing the role of spores in the life cycle can demystify the growth of plants like orchids or liverworts, which have unique gametophyte requirements. By appreciating this dual nature, we can better cultivate, conserve, and study the plant kingdom.

Does Milky Spore Kill All Grubs? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Bacterial Spores: Endospores are asexual, formed for survival, not reproduction

Bacterial spores, specifically endospores, are a remarkable survival mechanism in the microbial world. Unlike spores produced by plants or fungi, which often play a role in reproduction, bacterial endospores are strictly asexual structures. They are not formed to propagate the species but rather to ensure the bacterium’s survival under harsh conditions. This distinction is critical: while sexual spores involve genetic recombination and dispersal, endospores are a dormant, resilient form of the same bacterium, ready to revive when conditions improve.

Consider the process of endospore formation, known as sporulation. When a bacterium like *Bacillus anthracis* (the causative agent of anthrax) senses nutrient depletion or environmental stress, it initiates a complex series of steps to create an endospore. This structure is encased in multiple protective layers, including a cortex rich in peptidoglycan and a proteinaceous coat, making it resistant to heat, radiation, and chemicals. For example, endospores can survive boiling water for hours, a feat that vegetative bacterial cells cannot achieve. This durability is not for reproduction but for persistence, allowing the bacterium to endure until favorable conditions return.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the asexual nature of endospores is crucial in fields like food safety and medicine. In food preservation, for instance, pasteurization at 72°C for 15 seconds is effective against vegetative bacteria but insufficient to destroy endospores. High-pressure processing or autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes is required to eliminate these resilient forms. Similarly, in healthcare, endospores of *Clostridium difficile* can survive on surfaces for months, necessitating specialized disinfectants like bleach (5,000–10,000 ppm) for effective decontamination.

Comparatively, sexual spores in fungi and plants serve reproductive purposes, often involving dispersal mechanisms like wind or animals. Endospores, however, remain localized, attached to the bacterial cell until germination. This fundamental difference highlights the unique role of endospores as a survival strategy rather than a reproductive one. While sexual spores contribute to genetic diversity, endospores maintain the genetic identity of the parent bacterium, ensuring its lineage persists through adversity.

In conclusion, bacterial endospores are a testament to the ingenuity of microbial survival strategies. Their asexual nature and unparalleled resilience make them distinct from reproductive spores in other organisms. By focusing on survival rather than reproduction, endospores exemplify how bacteria adapt to extreme environments, posing challenges in industries from food production to healthcare. Understanding this distinction is key to effectively managing and mitigating the risks associated with these microscopic survivors.

Mastering Morel Mushroom Propagation: Effective Techniques to Spread Spores

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores can be either sexual or asexual, depending on the organism and the type of spore produced.

Asexual spores, such as conidia in fungi or endospores in bacteria, are produced by a single parent without the fusion of gametes and are genetically identical to the parent.

Sexual spores, like zygospores in fungi or meiospores in plants, result from the fusion of gametes and undergo meiosis, leading to genetic diversity.

No, the production of sexual or asexual spores depends on the organism. Some produce only one type, while others, like certain fungi, can produce both under different conditions.

Spores serve as a means of reproduction, dispersal, and survival in harsh conditions. Asexual spores allow for rapid reproduction, while sexual spores promote genetic diversity and adaptation.