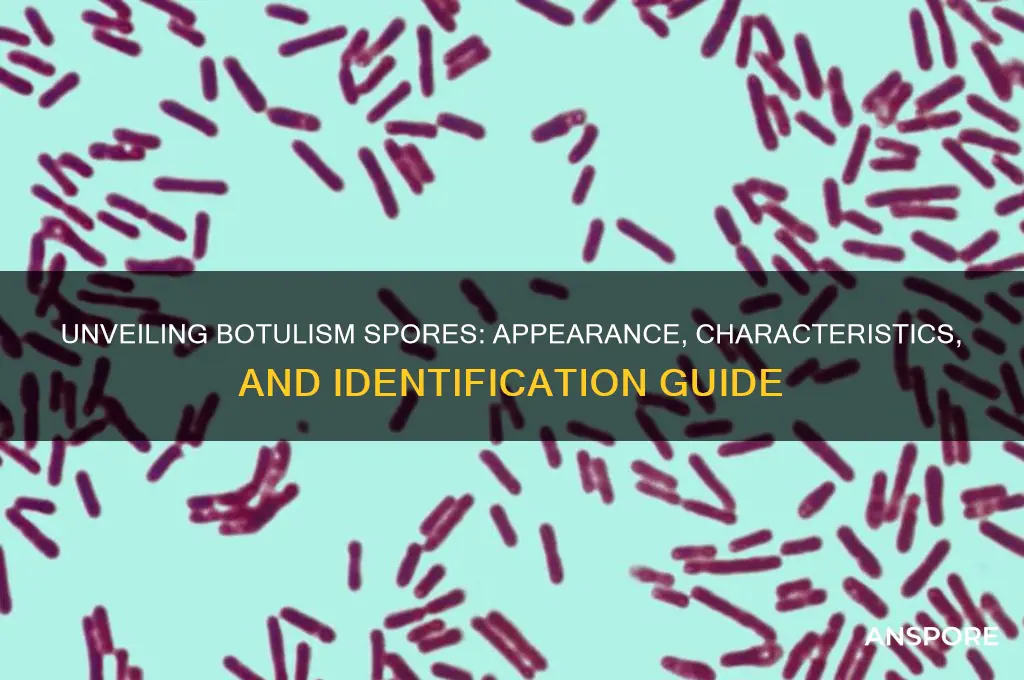

Botulism spores, produced by the bacterium *Clostridium botulinum*, are microscopic, rod-shaped, and highly resistant to extreme conditions such as heat, desiccation, and chemicals. These spores are typically colorless and cannot be seen with the naked eye, requiring a microscope for visualization. They are commonly found in soil, sediments, and marine environments, and can survive in dormant form for years until they encounter favorable conditions to germinate and produce the potent botulinum toxin, which causes botulism. Understanding their appearance and characteristics is crucial for identifying potential sources of contamination and preventing this serious, potentially fatal illness.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Shape and Size: Rod-shaped, 0.5-2 μm long, 0.2-0.8 μm wide, oval to cylindrical

- Spore Color: Typically colorless, appearing translucent or slightly opaque under a microscope

- Spore Arrangement: Often found singly or in chains, sometimes in clusters, depending on the strain

- Spore Resistance: Highly heat-resistant, surviving temperatures up to 121°C for 30 minutes

- Microscopic Appearance: Smooth, refractile, and surrounded by a protective exosporium layer

Spore Shape and Size: Rod-shaped, 0.5-2 μm long, 0.2-0.8 μm wide, oval to cylindrical

Botulism spores, the resilient forms of *Clostridium botulinum*, are microscopic marvels of survival. Their shape and size are critical to their function: rod-shaped, measuring 0.5–2 μm in length and 0.2–0.8 μm in width, with an oval to cylindrical appearance. This morphology is no accident. The rod shape maximizes surface area for nutrient absorption while maintaining structural integrity, a key feature for enduring harsh environments like soil, sediments, and improperly canned foods. Their diminutive size, invisible to the naked eye, allows them to evade detection until conditions are ideal for germination, posing a silent threat in contaminated products.

Analyzing these dimensions reveals their adaptive brilliance. The 0.5–2 μm length places them within the typical range for bacterial spores, ensuring they are small enough to remain airborne or suspended in liquids, yet large enough to house essential genetic material. The 0.2–0.8 μm width is a strategic compromise between compactness and functionality, enabling them to resist desiccation, heat, and chemicals. This size also facilitates their penetration into food matrices, where they can lie dormant for years. For context, a single spore, if ingested and activated, can produce enough botulinum toxin to cause severe illness, underscoring the importance of understanding their physical characteristics.

To visualize these spores, consider a grain of salt, roughly 100 μm across—botulism spores are 50 to 200 times smaller. Their oval to cylindrical shape distinguishes them from spherical spores of other bacteria, aiding in identification under a high-powered microscope. Laboratory technicians often use phase-contrast or electron microscopy to observe these structures, as their size falls below the resolution limit of standard light microscopes. For food safety professionals, recognizing this shape and size is crucial for implementing preventive measures, such as proper canning techniques (e.g., boiling low-acid foods for 10–20 minutes at 240°F) to destroy spores before they germinate.

Practical implications of these dimensions extend to everyday scenarios. For instance, home canners must ensure their equipment reaches temperatures above 240°F to eliminate spores, as lower temperatures may only activate them. Similarly, commercial food producers use high-pressure processing (HPP) to target spores’ structural weaknesses, exploiting their specific size and shape. Even in medical settings, understanding spore morphology aids in developing antitoxins and vaccines, as the rod shape influences how spores interact with host cells. By focusing on these precise measurements, we can better mitigate the risks associated with botulism spores, turning knowledge into actionable prevention.

Effective Ways to Eliminate Mold Spores in Your Home

You may want to see also

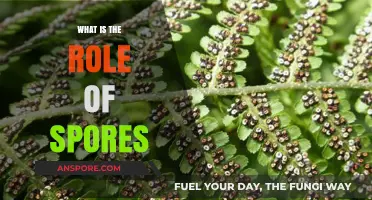

Spore Color: Typically colorless, appearing translucent or slightly opaque under a microscope

Botulism spores, the dormant forms of *Clostridium botulinum*, are masters of disguise in their natural environment. Under a microscope, their color—or rather, lack thereof—is a defining characteristic. Typically colorless, these spores appear translucent or slightly opaque, blending seamlessly into their surroundings. This near-invisibility is a survival tactic, allowing them to persist in soil, sediments, and even food products without detection. For microbiologists and food safety experts, this characteristic poses a challenge: identifying them requires specialized staining techniques or advanced imaging methods to reveal their presence.

To visualize botulism spores, researchers often employ techniques like phase-contrast microscopy or fluorescent staining. Without such tools, their colorless nature renders them nearly indistinguishable from their background. This transparency is not a flaw but a feature, enabling them to evade predators and harsh environmental conditions. For instance, in food preservation, their invisibility underscores the importance of heat treatment (e.g., boiling for at least 10 minutes) to destroy spores, as visual inspection alone is insufficient. Understanding this colorless trait is critical for developing effective detection and prevention strategies.

From a practical standpoint, the colorless nature of botulism spores highlights the limitations of relying on sight for food safety. Home canners, for example, must follow precise guidelines—such as using pressure canners at 240°F (116°C) for low-acid foods—to ensure spore destruction. Even slight deviations can allow spores to survive, leading to potential botulism outbreaks. The takeaway? Colorless spores demand proactive measures, not passive observation, to mitigate risk.

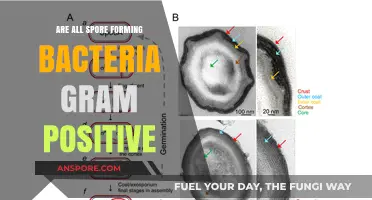

Comparatively, other bacterial spores, like those of *Bacillus anthracis*, exhibit distinct shapes or staining properties, making them easier to identify. Botulism spores, however, lack such distinguishing features, relying instead on their invisibility. This contrast underscores the unique challenge they pose. While anthrax spores might be detected through their rod-like shape or positive Gram stain, botulism spores require more sophisticated methods, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, to confirm their presence. This comparison highlights the need for tailored approaches in spore detection and management.

In conclusion, the colorless, translucent appearance of botulism spores under a microscope is both a biological marvel and a practical concern. Their invisibility necessitates a shift from visual inspection to proactive, science-based interventions. Whether in a laboratory or a kitchen, understanding this trait is essential for preventing botulism. By recognizing their stealthy nature, we can implement measures—from proper food processing to advanced diagnostic tools—that safeguard health and ensure safety.

Heat's Role in Spore Staining: Enhancing Accuracy and Visualization

You may want to see also

Spore Arrangement: Often found singly or in chains, sometimes in clusters, depending on the strain

Botulism spores, the resilient forms of *Clostridium botulinum*, exhibit a fascinating diversity in their arrangement, a characteristic that varies significantly across strains. This variability is not merely a curiosity but a critical factor in identifying and understanding the behavior of these spores in different environments. Whether found singly, in chains, or in clusters, the arrangement provides clues about the strain’s origin, survival strategies, and potential risks. For instance, spores in chains may suggest a more robust, interconnected structure, while singly occurring spores could indicate a more dispersed and adaptable form.

Analyzing spore arrangement requires precision and context. Laboratory techniques such as phase-contrast microscopy or electron microscopy reveal these patterns, with chains often appearing as linear sequences of oval or spherical spores, each measuring approximately 0.5 to 2.0 micrometers in diameter. Clusters, on the other hand, resemble small, irregular aggregates, which can complicate identification without proper magnification. Understanding these arrangements is essential for food safety professionals, as certain arrangements may correlate with higher resistance to heat or preservatives, influencing the effectiveness of sterilization processes.

From a practical standpoint, recognizing spore arrangement can guide preventive measures. For example, strains with clustered spores may require longer heating times (e.g., 121°C for 3–4 minutes) during food processing to ensure complete inactivation. Conversely, singly occurring spores might be more susceptible to standard pasteurization methods. Home canners and food producers should be particularly vigilant, as improper processing can allow these spores to survive and germinate, leading to botulism toxin production. Always follow USDA guidelines for pressure canning low-acid foods to mitigate this risk.

Comparatively, the arrangement of botulism spores contrasts with other bacterial spores, such as those of *Bacillus anthracis*, which typically form chains but lack clustering. This distinction highlights the unique adaptability of *C. botulinum* across diverse environments, from soil to improperly preserved foods. For instance, strains found in soil often exhibit singly occurring spores, facilitating dispersal, while foodborne strains may form clusters to enhance survival in nutrient-rich conditions. Such differences underscore the importance of strain-specific approaches in both research and safety protocols.

In conclusion, spore arrangement is a critical yet often overlooked aspect of botulism spore identification and management. Whether singly, in chains, or clusters, this characteristic offers valuable insights into strain behavior and informs effective prevention strategies. By leveraging this knowledge, professionals and individuals alike can better safeguard against the risks posed by these resilient microorganisms. Always prioritize proper food handling and processing techniques to minimize the threat of botulism.

How Long Do Mold Spores Survive on Your Clothes?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spore Resistance: Highly heat-resistant, surviving temperatures up to 121°C for 30 minutes

Botulism spores, the dormant forms of *Clostridium botulinum*, are microscopic in size, typically measuring 0.5 to 2.0 micrometers in diameter. Despite their minuscule dimensions, these spores possess an extraordinary ability to withstand extreme conditions, particularly high temperatures. This resilience is a critical factor in their survival and the challenges they pose in food safety and sterilization processes.

One of the most striking features of botulism spores is their resistance to heat. They can survive temperatures as high as 121°C (250°F) for up to 30 minutes, a level of tolerance that far exceeds that of most other bacterial spores. This resistance is attributed to their robust cell wall structure and the presence of dipicolinic acid, a molecule that stabilizes the spore’s DNA and proteins under stress. To put this into perspective, standard boiling water (100°C) is insufficient to destroy these spores, and even autoclaving, a method commonly used to sterilize medical equipment, requires precise conditions to ensure their eradication.

For practical purposes, this heat resistance necessitates specific precautions in food processing and preservation. Home canning, for instance, often involves boiling jars of food, but this is inadequate to eliminate botulism spores. Instead, a pressure canner is required to achieve temperatures above 100°C, typically around 116°C to 121°C, for a minimum of 20 to 100 minutes, depending on the food type and altitude. Failure to follow these guidelines can result in spore survival, leading to botulism toxin production in improperly processed foods.

The implications of spore resistance extend beyond home canning to industrial food production. Commercial sterilization processes, such as retorting, are designed to target these resilient spores, often using temperatures of 121°C for 3 to 5 minutes. However, even these methods are not foolproof, as variations in food composition, pH, and packaging can affect spore inactivation. For example, low-acid foods like vegetables, meats, and poultry are particularly susceptible to botulism contamination, requiring stricter processing conditions compared to high-acid foods like fruits and pickles.

Understanding the heat resistance of botulism spores underscores the importance of adhering to scientifically validated food safety protocols. Whether in a home kitchen or a large-scale manufacturing facility, precise temperature control and duration are non-negotiable. For individuals, this means investing in a reliable pressure canner and following tested recipes from reputable sources. For industries, it involves rigorous monitoring of sterilization processes and regular validation of equipment. By respecting the resilience of these microscopic survivors, we can mitigate the risk of botulism and ensure the safety of our food supply.

Heat-Resistant Bacterial Spores: The Scientist Behind the Discovery

You may want to see also

Microscopic Appearance: Smooth, refractile, and surrounded by a protective exosporium layer

Under a microscope, botulism spores reveal a distinct morphology that sets them apart from other bacterial spores. Their smooth surface is a defining feature, lacking the rough or irregular textures often seen in spores of different pathogens. This smoothness is not merely aesthetic; it contributes to their ability to evade detection by the immune system, making them particularly insidious. The refractile nature of these spores means they bend light, appearing almost like tiny, shimmering orbs under proper illumination. This optical property is a result of their dense, compact structure, which also aids in their survival in harsh environments.

The protective exosporium layer surrounding botulism spores is a critical adaptation for their resilience. This outer sheath acts as a shield, safeguarding the spore from heat, chemicals, and other environmental stressors. Unlike some spores that lack this layer, botulism spores can persist in soil, water, and even canned foods for years. For instance, in food preservation, the exosporium’s durability necessitates specific processing techniques, such as boiling at 121°C (250°F) for at least 3 minutes, to ensure complete destruction. This layer is not just a barrier but a key factor in the spore’s ability to cause botulism when conditions allow for germination.

Comparatively, the exosporium of botulism spores is thicker and more robust than that of many other bacterial spores, such as those of *Bacillus anthracis*. This heightened protection explains why botulism spores are notoriously difficult to eradicate in food processing environments. For home canners, understanding this microscopic feature underscores the importance of following precise sterilization protocols, such as using a pressure canner for low-acid foods, to prevent spore survival. Even a single surviving spore can germinate and produce deadly botulinum toxin under favorable conditions, such as anaerobic environments and temperatures between 25°C and 40°C (77°F and 104°F).

Practically, recognizing the microscopic appearance of botulism spores is less about identification—as specialized lab equipment is required—and more about appreciating the necessity of preventive measures. For example, infants under 12 months should never be fed honey, as it can contain botulism spores that their immature digestive systems cannot handle. Similarly, any home-canned food showing signs of spoilage, such as bulging lids or foul odors, should be discarded immediately, as these could indicate spore germination. By understanding the spore’s structure, we can better respect the invisible threats they pose and take appropriate precautions.

Unbelievable Lifespan: How Long Can Spores Survive in Extreme Conditions?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Botulism spores appear as small, oval-shaped structures, typically 1-2 micrometers in size, with a thick, resistant outer layer that makes them highly durable.

No, botulism spores are microscopic and cannot be seen without the aid of a microscope or specialized equipment.

Botulism spores are typically colorless or appear as faintly refractile (light-bending) structures under a microscope, making them difficult to distinguish without staining.

Botulism spores are similar in shape and size to other bacterial spores but are specifically identified through laboratory tests, such as toxin detection or DNA analysis, rather than visual appearance alone.

No, botulism spores are not visible in contaminated food, as they are microscopic and do not alter the appearance, smell, or taste of the food.

![[AROCELL] Botulcare Graphene Mask](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51lYyiyJBtL._AC_UL320_.jpg)