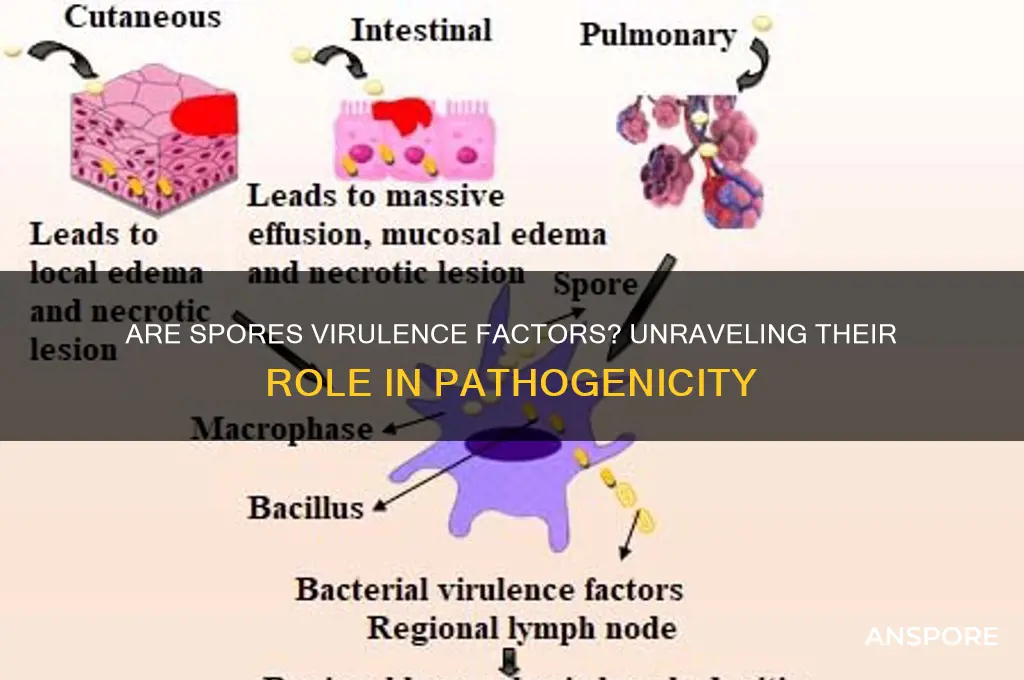

Spores, often produced by bacteria and fungi, are highly resilient structures primarily associated with survival in harsh environments. While their primary function is to ensure the organism's persistence, the question arises whether spores themselves can be considered virulence factors. Virulence factors are traits that enable pathogens to cause disease, and spores, by virtue of their ability to disseminate widely, resist host defenses, and germinate under favorable conditions, may contribute to pathogenicity. For instance, bacterial spores like those of *Clostridium difficile* and *Bacillus anthracis* can evade immune responses, colonize tissues, and initiate infection upon germination. Similarly, fungal spores, such as those of *Aspergillus* and *Cryptococcus*, can infiltrate the respiratory system and establish infections in immunocompromised hosts. Thus, while spores are not inherently virulent, their role in dissemination, persistence, and infection initiation suggests they can act as indirect virulence factors in certain contexts.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Spores are dormant, highly resistant structures produced by certain bacteria, fungi, and plants. They are not inherently virulence factors but can contribute to virulence under specific conditions. |

| Role in Virulence | Spores can enhance virulence by aiding in survival, dissemination, and persistence in hostile environments, increasing the likelihood of infection upon reaching a susceptible host. |

| Survival Mechanisms | Spores are resistant to extreme temperatures, desiccation, radiation, and chemicals, allowing them to persist in harsh conditions until they reach a favorable environment. |

| Dissemination | Spores can be easily dispersed through air, water, or vectors, facilitating the spread of pathogens over long distances. |

| Germination | Upon reaching a suitable environment, spores germinate into vegetative cells, which can then cause infection if the organism is pathogenic. |

| Immune Evasion | Some spores can evade host immune responses due to their resistant outer layers, delaying detection and clearance. |

| Examples of Pathogenic Spores | Clostridium difficile (causes antibiotic-associated diarrhea), Bacillus anthracis (causes anthrax), and Aspergillus spp. (causes aspergillosis in immunocompromised individuals). |

| Non-Pathogenic Spores | Many spore-forming organisms are non-pathogenic, such as Bacillus subtilis, which is used in probiotics and biotechnology. |

| Clinical Significance | Spores of pathogenic organisms can cause severe infections, especially in immunocompromised individuals, and are challenging to eradicate due to their resistance. |

| Research Focus | Ongoing research aims to understand spore germination mechanisms and develop strategies to inhibit spore-mediated infections. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Role of spore dormancy in pathogen survival

Spores, often considered a survival mechanism, play a pivotal role in the persistence and dissemination of pathogenic microorganisms. Their ability to enter a dormant state allows them to withstand extreme environmental conditions, such as desiccation, heat, and chemical disinfectants, which would otherwise be lethal to their vegetative forms. This dormancy is not merely a passive state but a highly regulated process that ensures the pathogen’s long-term survival. For instance, *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax, forms spores that can remain viable in soil for decades, posing a persistent threat to both animals and humans. Understanding the mechanisms of spore dormancy is crucial for developing strategies to disrupt this survival tactic and mitigate pathogen spread.

From an analytical perspective, spore dormancy serves as a virulence factor by enabling pathogens to evade host immune responses and antimicrobial treatments. During dormancy, spores exhibit minimal metabolic activity, making them invisible to many immune surveillance systems. This stealth mode allows them to persist in hostile environments, such as the human body, until conditions become favorable for germination and active infection. For example, *Clostridium difficile* spores can survive the acidic conditions of the stomach and germinate in the intestine, leading to severe gastrointestinal infections. The ability to remain dormant until reaching the target site enhances the pathogen’s virulence by ensuring successful colonization and disease establishment.

To counteract the survival advantage conferred by spore dormancy, targeted interventions must focus on disrupting the germination process. Practical strategies include the use of germinant inhibitors, which prevent spores from activating and transitioning to their vegetative, infectious form. For instance, research has shown that small molecule inhibitors can block the germination of *Bacillus cereus* spores by targeting specific receptors involved in the process. Additionally, environmental modifications, such as controlling humidity and temperature, can reduce the likelihood of spore germination in clinical and agricultural settings. These approaches highlight the importance of understanding spore biology to develop effective preventive measures.

Comparatively, spore dormancy in pathogens like *Aspergillus fumigatus* and *Cryptococcus neoformans* showcases the diversity of survival strategies among fungi. While bacterial spores are well-studied, fungal spores (conidia) also exploit dormancy to survive harsh conditions and disseminate widely. Fungal spores can remain airborne for extended periods, increasing their chances of reaching susceptible hosts. Unlike bacterial spores, fungal conidia often require specific triggers, such as nutrient availability or temperature shifts, to exit dormancy. This distinction underscores the need for tailored interventions that account for the unique characteristics of different spore-forming pathogens.

In conclusion, spore dormancy is a critical virulence factor that enhances pathogen survival and dissemination. By enabling microorganisms to withstand adverse conditions and evade detection, dormancy ensures their persistence in diverse environments. Practical strategies to disrupt germination and environmental control measures offer promising avenues for mitigating the threat posed by spore-forming pathogens. Recognizing the role of dormancy in pathogen survival not only advances our understanding of microbial virulence but also informs the development of targeted interventions to combat infectious diseases.

Effective Mold Removal: Clean Safely Without Spreading Spores

You may want to see also

Spore structure and immune evasion mechanisms

Spores, the dormant and highly resistant structures produced by certain bacteria and fungi, are not merely survival mechanisms but also sophisticated tools for immune evasion. Their unique structure—characterized by a thick, multilayered cell wall composed of materials like peptidoglycan, sporopollenin, and dipicolinic acid—renders them impervious to many environmental stressors, including heat, desiccation, and chemicals. This structural resilience is the first line of defense against host immune systems, as it prevents recognition and degradation by phagocytic cells and antimicrobial enzymes. For instance, the spores of *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax, can survive in soil for decades, only to germinate upon entry into a host, bypassing initial immune surveillance.

One of the most intriguing immune evasion mechanisms employed by spores is their ability to modulate host immune responses during germination. As spores transition to vegetative cells, they release enzymes and toxins that disrupt immune signaling pathways. For example, *Clostridium difficile* spores secrete proteases that degrade host antimicrobial peptides, while *B. anthracis* spores release lethal and edema toxins that inhibit phagocyte function. This dual strategy—structural resistance followed by active immune suppression—ensures that spores not only survive but also thrive in hostile host environments.

A closer examination of spore coat proteins reveals another layer of immune evasion. These proteins, which form the outermost layer of the spore, often mimic host molecules, allowing spores to "hide in plain sight." For instance, some fungal spores express proteins that resemble host glycoproteins, reducing their recognition by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on immune cells. This molecular mimicry is particularly effective in evading innate immunity, as it delays the activation of inflammatory responses, giving spores ample time to germinate and establish infection.

Practical implications of spore immune evasion are significant, especially in clinical settings. For example, patients with compromised immune systems, such as those undergoing chemotherapy or living with HIV, are at higher risk of spore-mediated infections. To mitigate this, healthcare providers should focus on environmental decontamination, particularly in hospitals, using spore-specific disinfectants like hydrogen peroxide vapor or chlorine dioxide. Additionally, early detection of spore germination through molecular diagnostics can enable timely administration of antibiotics or antifungals, such as vancomycin for *C. difficile* or ciprofloxacin for anthrax, at effective doses (e.g., 500 mg every 6 hours for ciprofloxacin in adults).

In conclusion, the structure and immune evasion mechanisms of spores underscore their role as potent virulence factors. Their ability to withstand harsh conditions, modulate host immunity, and exploit molecular mimicry highlights the evolutionary sophistication of these microbial survival strategies. Understanding these mechanisms not only advances our knowledge of pathogenesis but also informs the development of targeted therapies and preventive measures, ensuring better outcomes for vulnerable populations.

Exploring Fungi Reproduction: Sexual, Asexual, or Both?

You may want to see also

Germination triggers and host infection timing

Spores, often considered dormant survival structures, are not inherently virulent. However, their ability to germinate at precise times and locations within a host can significantly enhance pathogenicity. Germination triggers and host infection timing are critical factors that transform spores from inert entities into active agents of disease. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for developing strategies to disrupt the infection process.

Triggers for Germination: A Delicate Balance

Spores remain dormant until specific environmental cues signal favorable conditions for growth. These triggers vary widely among species but often include changes in temperature, pH, nutrient availability, and exposure to specific chemicals. For instance, *Clostridium botulinum* spores germinate in response to L-alanine and inositol, compounds present in the gastrointestinal tract. Similarly, *Bacillus anthracis* spores require a combination of nutrients and temperature shifts to initiate germination. These triggers are not random; they ensure spores activate only when they can successfully colonize and exploit the host environment.

Timing of Host Infection: A Strategic Advantage

The timing of spore germination within a host is a finely tuned process that maximizes virulence. Premature germination outside the host wastes energy and exposes spores to defenses like stomach acid or immune cells. Conversely, delayed germination may allow the host to clear the spores before infection can establish. Pathogens like *Aspergillus fumigatus* have evolved to germinate rapidly in the warm, nutrient-rich environment of the lungs, enabling them to evade immune responses and establish infection. This strategic timing ensures spores exploit the host’s vulnerabilities at the optimal moment.

Practical Implications: Disrupting Germination for Disease Prevention

Understanding germination triggers and timing offers opportunities to intervene in the infection process. For example, inhibiting key germinants like L-alanine could prevent *C. botulinum* spores from activating in the gut. Similarly, manipulating environmental conditions, such as temperature or pH, might delay or halt spore germination in clinical settings. In agriculture, controlling humidity and nutrient availability can reduce spore activation in crops, minimizing fungal infections. These targeted approaches could complement traditional antibiotics and antifungals, especially as resistance rises.

Comparative Analysis: Host vs. Environmental Germination

While some spores germinate exclusively within hosts, others can activate in both host and environmental settings. For example, *Bacillus cereus* spores germinate in soil but also in the human gut, showcasing adaptability. In contrast, *Cryptococcus neoformans* spores primarily germinate in the lungs, highlighting specialization. This distinction underscores the importance of context-specific strategies for controlling spore-mediated infections. By studying these differences, researchers can develop tailored interventions that target either environmental reservoirs or host-specific germination processes.

Spores themselves are not virulence factors, but their germination triggers and timing within a host are pivotal in disease progression. By manipulating these mechanisms, we can disrupt the infection cycle and mitigate pathogenicity. Whether through chemical inhibitors, environmental controls, or targeted therapies, understanding germination dynamics offers a powerful avenue for combating spore-borne diseases. This knowledge bridges the gap between basic microbiology and practical disease prevention, paving the way for innovative solutions.

Can Heat Kill Fungal Spores? Exploring Their Resistance to High Temperatures

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spore-mediated toxin delivery systems

Spores, often recognized for their resilience, serve as more than just survival structures for certain pathogens. They act as sophisticated delivery systems for toxins, enhancing virulence in ways that are both ingenious and alarming. For instance, *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax, encapsulates its lethal toxin within a spore matrix. Upon germination, the spore releases the toxin, which disrupts host cell signaling and leads to rapid disease progression. This mechanism underscores how spores can function as Trojan horses, bypassing host defenses to deliver potent virulence factors directly to target cells.

Consider the practical implications of spore-mediated toxin delivery in a clinical or bioterrorism context. Inhalation of just 8,000 to 50,000 spores of *B. anthracis* can initiate anthrax infection, with lethal toxin concentrations as low as 0.0002 ng/mL causing systemic damage. This efficiency highlights the importance of early detection and intervention. Decontamination protocols, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 30 minutes or using spore-specific disinfectants like chlorine dioxide, are critical to neutralizing these threats. Understanding the spore’s role in toxin delivery is essential for developing targeted therapies, such as toxin-neutralizing antibodies or germination inhibitors, to disrupt this virulence strategy.

From an evolutionary standpoint, spore-mediated toxin delivery represents a remarkable adaptation. Pathogens like *Clostridium botulinum* and *C. tetani* produce spores that, upon germination, release neurotoxins capable of causing botulism and tetanus, respectively. These toxins are among the most potent known, with botulinum toxin’s LD50 (lethal dose for 50% of the population) estimated at 1 ng/kg in humans. The spore’s ability to protect and deliver these toxins ensures their survival in harsh environments and maximizes their impact once inside a host. This dual functionality—survival and virulence—illustrates the spore’s role as a key virulence factor.

For researchers and healthcare professionals, studying spore-mediated toxin delivery systems offers actionable insights. Techniques like spore germination assays and toxin quantification using ELISA can help assess the risk posed by spore-forming pathogens. Additionally, vaccines targeting spore-associated toxins, such as the anthrax vaccine adsorbed (AVA), provide a proactive defense. Public health strategies should emphasize education on spore-contaminated environments, particularly in agricultural and industrial settings where exposure risk is high. By focusing on the spore’s role in toxin delivery, we can develop more effective prevention and treatment strategies against these formidable pathogens.

Are All Anaerobes Spore-Forming? Unraveling the Microbial Mystery

You may want to see also

Environmental persistence and disease transmission via spores

Spores, with their remarkable resilience, serve as a stealthy mechanism for environmental persistence and disease transmission. Unlike vegetative cells, spores can withstand extreme conditions—desiccation, heat, and chemicals—allowing them to remain dormant yet viable for years, even decades. This durability enables pathogens like *Bacillus anthracis* (causative agent of anthrax) and *Clostridium difficile* to persist in soil, water, and healthcare settings, posing a continuous threat to human and animal health. Their ability to survive in diverse environments ensures that even in the absence of active infection, spores remain a reservoir for future outbreaks.

Consider the transmission dynamics of spore-forming pathogens. Spores can be aerosolized, ingested, or come into contact with mucous membranes, making them versatile in their routes of infection. For instance, inhalation of *B. anthracis* spores, even in minute quantities (as few as 8,000–50,000 spores), can lead to inhalational anthrax, a severe and often fatal disease. Similarly, *C. difficile* spores, resistant to routine cleaning agents, can contaminate hospital surfaces, leading to nosocomial infections, particularly in immunocompromised or elderly patients. This highlights the dual role of spores: not only as survival structures but also as efficient vectors for disease dissemination.

To mitigate the risks associated with spore-mediated transmission, targeted strategies are essential. In healthcare settings, spore-specific disinfectants like chlorine-based solutions (e.g., 1,000–5,000 ppm sodium hypochlorite) are recommended for surface decontamination. For agricultural environments, soil treatment with heat or chemical agents can reduce spore viability, though this must be balanced with ecological impact. Public health measures, such as water filtration systems and air quality monitoring, can further limit spore exposure. These interventions underscore the importance of understanding spore behavior to disrupt their transmission pathways effectively.

Comparatively, the environmental persistence of spores contrasts sharply with that of non-spore-forming pathogens, which often rely on immediate host-to-host transmission. While viruses like influenza require frequent replication to survive, spores can bide their time, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate and cause infection. This distinction necessitates a shift in control strategies—from reactive outbreak management to proactive environmental surveillance and decontamination. By focusing on spore-specific vulnerabilities, such as their reliance on specific triggers for germination, we can develop more nuanced and effective prevention methods.

In conclusion, spores are not merely passive survival structures but active contributors to disease transmission. Their environmental persistence and ability to exploit diverse routes of infection make them formidable virulence factors. Addressing this challenge requires a multifaceted approach—combining scientific understanding, targeted interventions, and public health vigilance. By recognizing spores as key players in pathogen ecology, we can better protect against the diseases they cause and reduce their impact on global health.

Does Bleach Kill Mold Spores? Uncovering the Truth Behind the Myth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, spores are often considered virulence factors because they enhance a pathogen's ability to survive in harsh environments, evade host defenses, and persist until conditions are favorable for infection.

Spores contribute to virulence by providing resistance to heat, desiccation, antibiotics, and immune responses, allowing pathogens like *Clostridium difficile* and *Bacillus anthracis* to remain viable and cause disease when opportunities arise.

No, only certain bacteria and fungi produce spores. Not all pathogens rely on spores for virulence; some use other mechanisms like toxins, adhesins, or invasive enzymes to cause disease.

Spores themselves do not directly cause disease but act as survival structures. However, their ability to persist and germinate into active, pathogenic forms in a host environment makes them critical to the overall virulence of spore-forming pathogens.