Multicellular spore-producing organisms, such as fungi and plants, exhibit complex life cycles that involve alternating phases of haploid and diploid stages. In these organisms, the diploid phase typically arises from the fusion of haploid gametes during sexual reproduction, resulting in a zygote that undergoes mitosis to form a multicellular sporophyte. The sporophyte then produces spores through meiosis, which are haploid and give rise to the gametophyte generation. While the sporophyte is indeed diploid, the overall life cycle includes both haploid and diploid stages, making the answer to whether these organisms are diploid dependent on the specific phase being considered. Understanding this alternation of generations is crucial for grasping the reproductive strategies and genetic diversity of multicellular spore-producing organisms.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Life Cycle Overview: Alternation of generations between diploid sporophyte and haploid gametophyte phases in multicellular organisms

- Sporophyte Dominance: Diploid phase predominates in vascular plants, producing spores via meiosis for reproduction

- Gametophyte Role: Haploid phase produces gametes; diploid zygote develops into sporophyte in plant life cycles

- Spore Formation: Meiosis in sporophyte reduces chromosome number, forming haploid spores for dispersal

- Diploid vs Haploid: Multicellular organisms alternate between diploid (sporophyte) and haploid (gametophyte) stages

Life Cycle Overview: Alternation of generations between diploid sporophyte and haploid gametophyte phases in multicellular organisms

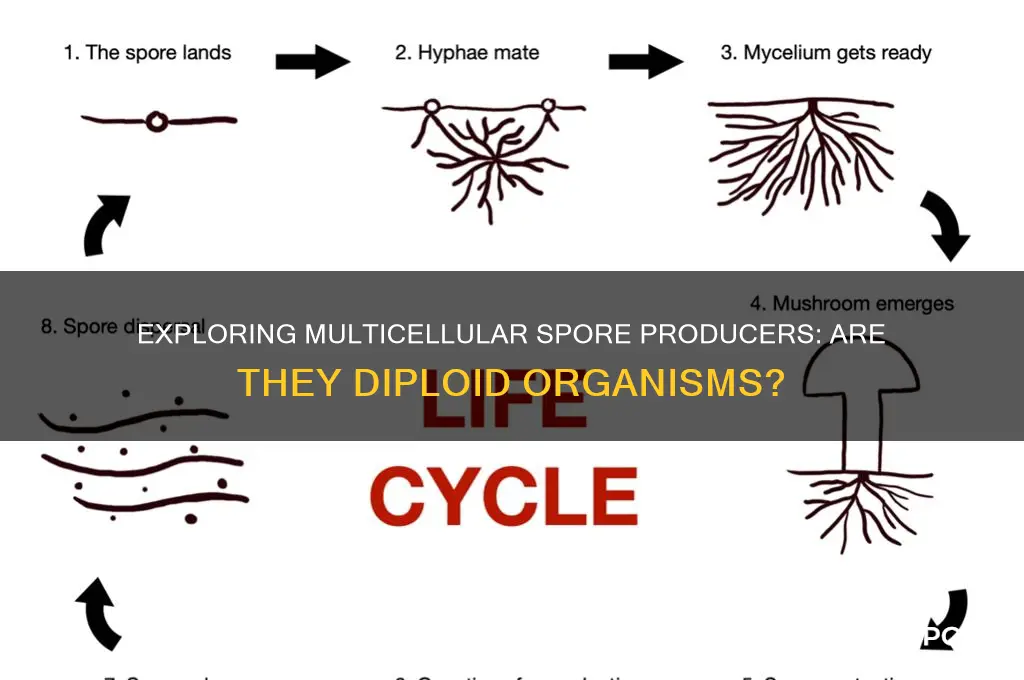

Multicellular spore-producing organisms, such as plants and some algae, exhibit a fascinating life cycle known as alternation of generations. This cycle involves two distinct phases: the diploid sporophyte and the haploid gametophyte. Each phase plays a critical role in the organism's reproduction and survival, ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability. The sporophyte phase, being diploid, produces spores through meiosis, while the gametophyte phase, haploid, generates gametes for sexual reproduction. This alternating pattern is a cornerstone of their life cycle, balancing stability and innovation.

To understand this process, consider the lifecycle of a fern. The visible fern plant is the sporophyte generation, which produces spores on the undersides of its leaves. These spores develop into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes, often hidden in the soil. The gametophyte, though small, is essential; it produces both sperm and egg cells. When conditions are right, sperm swim to fertilize the egg, resulting in a new sporophyte. This alternation ensures that genetic recombination occurs, enhancing the species' ability to adapt to changing environments.

From an analytical perspective, the alternation of generations is a strategic evolutionary adaptation. By switching between diploid and haploid phases, these organisms maximize their reproductive efficiency. The sporophyte phase, with its greater genetic stability, is better suited for growth and resource accumulation, while the gametophyte phase, with its reduced chromosome set, facilitates rapid reproduction and dispersal. This division of labor allows the organism to thrive in diverse habitats, from lush forests to arid deserts.

For those studying or teaching this concept, a practical tip is to use visual aids to illustrate the lifecycle. Diagrams or models showing the transition from sporophyte to gametophyte and back can clarify complex processes. Additionally, hands-on activities, such as observing fern spores under a microscope or growing moss gametophytes in a controlled environment, can deepen understanding. These methods make abstract concepts tangible, fostering a more intuitive grasp of alternation of generations.

In conclusion, the alternation of generations between diploid sporophyte and haploid gametophyte phases is a remarkable feature of multicellular spore-producing organisms. It ensures genetic diversity, enhances adaptability, and optimizes reproductive strategies. By examining specific examples and employing practical teaching tools, one can fully appreciate the elegance and efficiency of this lifecycle. Whether in a classroom or a research setting, understanding this process provides valuable insights into the biology of these organisms.

Are Mold Spores Carcinogens? Uncovering the Health Risks and Facts

You may want to see also

Sporophyte Dominance: Diploid phase predominates in vascular plants, producing spores via meiosis for reproduction

In the life cycles of vascular plants, the sporophyte generation—the diploid phase—is not just a fleeting stage but the dominant, long-lasting form. This contrasts sharply with non-vascular plants like mosses, where the gametophyte (haploid phase) takes center stage. For example, in ferns, the large, visible plant we typically recognize is the sporophyte, which produces spores through meiosis. These spores then develop into tiny, often inconspicuous gametophytes, completing the cycle. This dominance of the diploid phase is a hallmark of vascular plants, reflecting their evolutionary adaptation to terrestrial environments.

To understand sporophyte dominance, consider the structural and functional advantages it confers. Vascular plants, such as trees and flowering plants, rely on their sporophytes to develop extensive root systems, sturdy stems, and leaves—features that enhance resource acquisition and survival. The sporophyte’s diploid genome provides genetic stability, reducing the risk of mutations that could arise in a haploid phase. Meiosis in the sporophyte produces haploid spores, which are dispersed and grow into gametophytes. While gametophytes are short-lived and dependent on moisture for reproduction, sporophytes thrive in diverse conditions, ensuring the species’ continuity.

From a practical standpoint, sporophyte dominance has significant implications for horticulture and agriculture. For instance, when propagating plants like orchids or ferns, understanding the sporophyte’s role is crucial. Spores, being haploid, are genetically diverse, but the sporophyte’s stability ensures consistent traits in cultivated varieties. Gardeners and farmers can leverage this by selecting robust sporophytes for cloning or breeding, bypassing the gametophyte stage entirely. This approach is evident in techniques like tissue culture, where sporophyte cells are grown in vitro to produce genetically identical plants.

Comparatively, the dominance of the sporophyte in vascular plants sets them apart from algae and fungi, where haploid or dikaryotic phases often prevail. This distinction highlights the evolutionary success of sporophyte dominance in colonizing land. For example, while fungal spores are typically haploid, vascular plant spores are the product of a diploid sporophyte, allowing for greater complexity and size. This difference underscores the adaptive significance of the diploid phase in vascular plants, enabling them to dominate terrestrial ecosystems.

In conclusion, sporophyte dominance in vascular plants is a testament to the efficiency of the diploid phase in ensuring survival and reproduction. By producing spores via meiosis, the sporophyte not only perpetuates the species but also maintains genetic stability and structural integrity. Whether in natural ecosystems or cultivated settings, this dominance shapes the biology and utility of vascular plants, making it a cornerstone of plant life cycles. Understanding this phenomenon offers valuable insights for both scientific study and practical applications in agriculture and horticulture.

Streptococcus and Spore Formation: Unraveling the Bacterial Mystery

You may want to see also

Gametophyte Role: Haploid phase produces gametes; diploid zygote develops into sporophyte in plant life cycles

Multicellular spore-producing organisms, such as plants and certain fungi, exhibit a unique alternation of generations, where both haploid and diploid phases are multicellular. In this life cycle, the gametophyte plays a pivotal role as the haploid phase, responsible for producing gametes that ultimately give rise to the diploid sporophyte. This dynamic interplay ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, hallmarks of successful evolution in these organisms.

Consider the life cycle of a fern, a classic example of this alternation. The gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure, develops from a spore and is haploid, containing a single set of chromosomes. Its sole purpose is to produce gametes—sperm and eggs—through mitosis. When fertilization occurs, the resulting zygote is diploid, marking the beginning of the sporophyte generation. This sporophyte, the familiar fern plant, then produces spores via meiosis, completing the cycle. The gametophyte’s role is thus critical: it bridges the gap between generations, ensuring the continuity of the species.

From an analytical perspective, the gametophyte’s haploid nature is advantageous for genetic variation. Haploid organisms can more readily express recessive traits, allowing for natural selection to act on a broader range of genetic material. For instance, in mosses, the gametophyte is the dominant phase, and its haploid state facilitates rapid adaptation to environmental changes. In contrast, the sporophyte, being diploid, provides stability and resources for spore production. This division of labor underscores the efficiency of the alternation of generations.

Practically, understanding the gametophyte’s role is essential for horticulture and agriculture. For example, in breeding programs, manipulating the gametophyte phase can enhance desirable traits in crops. Techniques like haploid induction, where plants are treated with chemicals (e.g., 0.1–0.5% colchicine) to produce haploid gametophytes, are used to accelerate breeding cycles. Similarly, in tissue culture, gametophytes are often cultured in vitro under controlled conditions (22–25°C, 16-hour photoperiod) to study their development and optimize gamete production.

In conclusion, the gametophyte’s role as the haploid phase is not merely a step in the life cycle but a cornerstone of evolutionary success in multicellular spore-producing organisms. Its ability to produce gametes and give rise to the diploid sporophyte ensures genetic diversity, adaptability, and continuity. Whether in the wild or in controlled environments, this phase exemplifies the intricate balance between stability and innovation in nature.

Effective Ways to Eliminate Airborne Mold Spores in Your Home

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spore Formation: Meiosis in sporophyte reduces chromosome number, forming haploid spores for dispersal

Multicellular spore-producing organisms, such as ferns, mosses, and fungi, exhibit a unique life cycle that alternates between diploid and haploid phases. The sporophyte generation, which is diploid, undergoes meiosis to produce haploid spores, a process central to their reproductive strategy. This reduction in chromosome number is not merely a biological curiosity but a critical adaptation for survival and dispersal. By forming haploid spores, these organisms ensure genetic diversity and increase their chances of colonizing new environments.

Consider the fern as an illustrative example. The fern plant we typically observe is the sporophyte, a diploid organism. Within its leaves, or fronds, specialized structures called sporangia develop. Inside these sporangia, meiosis occurs, halving the chromosome number and producing haploid spores. These spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind or water, allowing ferns to propagate across diverse habitats. Once a spore lands in a suitable environment, it germinates into a gametophyte, a haploid organism that produces gametes for sexual reproduction, thus completing the life cycle.

From an analytical perspective, spore formation through meiosis serves multiple evolutionary advantages. First, it reduces the genetic material in spores, making them smaller and more efficient for dispersal. Second, the haploid phase introduces genetic recombination during fertilization, enhancing adaptability to changing environments. For instance, fungi like mushrooms release billions of spores, ensuring that at least some will encounter favorable conditions. This strategy contrasts with seed-producing plants, which invest more resources in protecting and nourishing their offspring but produce fewer dispersive units.

For those interested in cultivating spore-producing organisms, understanding this process is crucial. In horticulture, fern spores are sown on a sterile medium, such as a mix of peat and perlite, and kept in a humid, shaded environment to encourage gametophyte growth. Similarly, mushroom cultivators use spore syringes to inoculate substrates like grain or sawdust, ensuring optimal conditions for mycelium development. Patience is key, as spore germination can take weeks, depending on species and environmental factors.

In conclusion, spore formation via meiosis in the sporophyte is a sophisticated mechanism that balances genetic diversity with efficient dispersal. This process underscores the resilience of multicellular spore-producing organisms, enabling them to thrive in diverse ecosystems. Whether in the wild or in cultivation, appreciating this biological phenomenon enhances our ability to study, preserve, and utilize these organisms effectively.

Are Spore Syringes Illegal? Understanding Legal Boundaries and Risks

You may want to see also

Diploid vs Haploid: Multicellular organisms alternate between diploid (sporophyte) and haploid (gametophyte) stages

Multicellular spore-producing organisms, such as plants and some algae, exhibit a unique life cycle characterized by alternating diploid and haploid stages. This phenomenon, known as the alternation of generations, is a cornerstone of their reproductive strategy. The diploid sporophyte generation produces spores through meiosis, which then develop into the haploid gametophyte generation. This gametophyte, in turn, produces gametes (sperm and eggs) that fuse during fertilization to form a new sporophyte, completing the cycle.

Consider the life cycle of a fern as a practical example. The large, leafy fern plant you see is the diploid sporophyte. On the underside of its fronds, it produces spores that, when released, grow into small, heart-shaped gametophytes. These gametophytes are haploid and produce gametes. When sperm from one gametophyte fertilizes an egg on another, a new sporophyte begins to grow, eventually overshadowing its parent gametophyte. This alternation ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, as the haploid phase allows for recombination and the diploid phase provides stability.

From an analytical perspective, the alternation between diploid and haploid stages serves as a biological safeguard against genetic stagnation. The haploid gametophyte phase is particularly vulnerable to mutations, but it also provides an opportunity for natural selection to act on new genetic variations. In contrast, the diploid sporophyte phase offers stability, as recessive mutations are masked by dominant alleles. This dual-phase system maximizes evolutionary potential while minimizing risks, a strategy that has proven successful over millions of years.

For those studying or working with these organisms, understanding this alternation is crucial. For instance, in agriculture, knowing the life cycle of crop plants can optimize breeding programs. In horticulture, recognizing the gametophyte stage of ferns or mosses can aid in propagation efforts. Practical tips include controlling humidity and light to encourage spore germination and using sterile techniques to prevent contamination during gametophyte cultivation. This knowledge bridges the gap between theoretical biology and applied sciences.

In conclusion, the alternation between diploid sporophyte and haploid gametophyte stages is not just a biological curiosity but a fundamental mechanism ensuring the survival and diversity of multicellular spore-producing organisms. By studying this cycle, we gain insights into evolution, genetics, and practical applications in fields like agriculture and conservation. Whether you're a researcher, educator, or enthusiast, grasping this concept unlocks a deeper appreciation for the complexity and elegance of life's strategies.

Do Mold Spores Fluctuate with Seasons? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, multicellular spore-producing organisms can be either diploid or haploid, depending on their life cycle stage.

The diploid phase, or sporophyte, is the stage where the organism has two sets of chromosomes and produces spores through meiosis.

Yes, most multicellular spore-producing organisms, such as plants and fungi, exhibit alternation of generations between haploid (gametophyte) and diploid (sporophyte) phases.

Spores are typically haploid, as they are produced by the diploid sporophyte through meiosis, reducing the chromosome number by half.

No, they cannot exist solely in the diploid phase; they must alternate with a haploid phase to complete their life cycle, ensuring genetic diversity through sexual reproduction.