The question of whether spores are dead or if there’s something more to their state is a fascinating intersection of biology and microbiology. Spores, produced by organisms like bacteria, fungi, and plants, are often described as dormant or inactive, but this raises intriguing debates about their true nature. Are they simply in a state of suspended animation, waiting for optimal conditions to revive, or is there a deeper biological mechanism at play? Understanding whether spores are truly dead or merely in a highly resilient, non-living phase could shed light on their survival strategies, evolutionary advantages, and potential applications in fields like medicine, agriculture, and astrobiology. This exploration challenges our definitions of life, death, and the boundaries in between.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spores vs. Dormancy: Are spores truly dead, or are they dormant, waiting for optimal conditions to revive

- Environmental Triggers: What external factors (e.g., moisture, heat) activate spores if they’re not dead

- Metabolic Activity: Do spores exhibit minimal metabolic activity, suggesting they’re alive but inactive

- Survival Mechanisms: How do spores withstand extreme conditions if they’re not dead

- Scientific Definitions: Does the term dead apply to spores, or is it a misnomer

Spores vs. Dormancy: Are spores truly dead, or are they dormant, waiting for optimal conditions to revive?

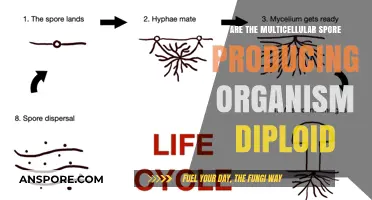

Spores, often mistaken for lifeless remnants, are in fact marvels of biological resilience. These microscopic structures, produced by bacteria, fungi, and plants, are not dead but exist in a state of dormancy. This dormancy is a survival strategy, allowing spores to withstand extreme conditions such as heat, cold, and desiccation. For example, bacterial endospores can survive boiling temperatures for hours, while fungal spores can persist in soil for decades. This ability to "pause" life until optimal conditions return challenges the notion that spores are inert or lifeless.

To understand dormancy, consider it a biological time capsule. Spores reduce their metabolic activity to near-zero levels, conserving energy and resources. This state is not death but a strategic withdrawal from active life. For instance, fungal spores remain viable in nutrient-poor environments, waiting for moisture and warmth to trigger germination. Similarly, plant spores, like those of ferns, can lie dormant in soil for years, only sprouting when conditions are ideal. This distinction between dormancy and death is crucial: spores are not dead; they are biding their time.

From a practical standpoint, recognizing spores as dormant rather than dead has significant implications. In agriculture, understanding spore dormancy helps optimize seed treatment and soil management. For example, treating seeds with specific chemicals or exposing them to controlled temperatures can break dormancy, enhancing germination rates. In medicine, this knowledge aids in combating spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridium botulinum*, which can survive in dormant states until activated in the human body. By targeting dormancy mechanisms, scientists can develop more effective strategies to control or eliminate these threats.

Comparatively, the dormancy of spores contrasts with true death, which is irreversible. While dead cells disintegrate and lose function, dormant spores retain the capacity to revive. This distinction is evident in laboratory studies where spores, once exposed to favorable conditions, resume metabolic activity within hours. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores, when rehydrated and provided with nutrients, rapidly return to vegetative growth. This ability to "come back to life" underscores the dynamic nature of dormancy, setting it apart from the finality of death.

In conclusion, spores are not dead but dormant, embodying a sophisticated survival mechanism. Their ability to endure harsh conditions and revive under optimal circumstances highlights the ingenuity of nature. Whether in agriculture, medicine, or ecology, understanding this distinction empowers us to harness or control spore behavior effectively. Spores, far from being lifeless, are silent sentinels waiting for their moment to thrive.

Effective Ways to Eliminate Black Mold Spores in Your Home

You may want to see also

Environmental Triggers: What external factors (e.g., moisture, heat) activate spores if they’re not dead?

Spores, often mistaken for dormant or dead entities, are in fact highly resilient survival structures produced by various organisms, including bacteria, fungi, and plants. Their ability to withstand harsh conditions is remarkable, but they are not invincible. Activation from dormancy is a complex process influenced by specific environmental triggers. Understanding these triggers is crucial for fields ranging from agriculture to medicine, as they dictate when and how spores spring back to life.

The Role of Moisture: A Universal Key

Moisture is perhaps the most critical environmental trigger for spore activation. For fungal spores, such as those of *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, water availability is essential to initiate metabolic processes. Studies show that relative humidity levels above 70% can activate fungal spores within hours, while bacterial spores, like those of *Bacillus anthracis*, require free water to break dormancy. In practical terms, controlling humidity in storage areas—keeping it below 60%—can prevent unwanted spore germination. For gardeners, ensuring soil moisture is consistent but not waterlogged can manage fungal spore activity effectively.

Temperature: The Catalyst for Change

Heat acts as a secondary but equally important trigger. Most spores remain dormant in extreme cold or heat, but specific temperature ranges activate them. For instance, *Clostridium botulinum* spores germinate optimally between 30°C and 40°C, while *Alternaria* spores thrive at 20°C to 25°C. Food preservation techniques, such as pasteurization (heating to 72°C for 15 seconds), target these temperature sensitivities to destroy spores in beverages and canned goods. Conversely, in agriculture, monitoring soil temperatures can predict fungal outbreaks, allowing for timely interventions like fungicide application.

Nutrient Availability: The Signal to Awaken

Spores are not merely passive entities waiting for moisture or heat; they also respond to nutrient availability. Organic compounds like sugars, amino acids, and vitamins act as chemical signals that trigger germination. For example, *Fusarium* spores require nitrogen sources like ammonium or nitrate to activate. In industrial settings, sterilizing surfaces with disinfectants that remove organic residues can prevent spore activation. Homeowners can reduce mold growth by promptly cleaning food spills and maintaining dry, well-ventilated spaces.

Light and pH: The Overlooked Influencers

While less studied, light and pH levels also play roles in spore activation. Certain fungal spores, such as those of *Neurospora crassa*, germinate in response to light exposure, particularly in the blue spectrum (450–470 nm). Similarly, pH shifts can trigger spores; *Bacillus* spores, for instance, activate more readily in neutral to slightly alkaline environments (pH 7–8). In aquaculture, maintaining optimal pH levels in water systems can prevent bacterial spore outbreaks. For indoor plants, using grow lights with filtered blue wavelengths can inadvertently encourage fungal spore germination, so balancing light exposure is key.

Practical Takeaways for Control and Prevention

Understanding these environmental triggers allows for targeted strategies to manage spore activation. In healthcare, sterilizing equipment at temperatures above 121°C (autoclaving) ensures spore destruction. In agriculture, rotating crops and adjusting irrigation schedules can disrupt spore germination cycles. For homeowners, simple measures like fixing leaks, using dehumidifiers, and storing food in airtight containers can prevent mold and bacterial growth. By manipulating these external factors, we can control spore behavior, whether to harness their benefits or mitigate their risks.

Do Fungi Produce Spores Above Ground? Exploring Fungal Reproduction

You may want to see also

Metabolic Activity: Do spores exhibit minimal metabolic activity, suggesting they’re alive but inactive?

Spores, often likened to nature’s survival capsules, challenge our understanding of life and dormancy. While they appear inert, recent studies suggest spores maintain minimal metabolic activity, blurring the line between alive and inactive. This residual activity includes low-level enzyme function and DNA repair mechanisms, which enable spores to endure extreme conditions like heat, radiation, and desiccation. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores exhibit trace ATP production, a hallmark of metabolic processes, even in states of apparent quiescence. This raises a critical question: does this minimal activity signify life, or is it merely a programmed response to ensure future revival?

To explore this, consider the analogy of a hibernation state in animals. Just as bears reduce metabolic activity to survive winter, spores downregulate processes while retaining essential functions. However, unlike hibernating animals, spores lack immediate responsiveness to stimuli. Their metabolic activity is so minimal—often below detectable thresholds—that it’s easy to mistake them for dead. Yet, this activity is purposeful, preserving cellular integrity for decades or even centuries. For example, spores of *Clostridium botulinum* can remain viable in soil for over 100 years, thanks to this subtle metabolic persistence.

Practical implications of this phenomenon are significant, particularly in sterilization protocols. Standard methods like autoclaving (121°C for 15–20 minutes) are designed to eliminate spores, but their resilience stems from this low-level metabolic activity. Spores repair DNA damage caused by heat or chemicals, necessitating more aggressive treatments like prolonged exposure to hydrogen peroxide or gamma radiation. Understanding this minimal activity helps refine sterilization techniques, ensuring spores are not just dormant but truly inactivated. For instance, in medical settings, spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridioides difficile* require specific disinfectants (e.g., chlorine-based solutions at 5,000–10,000 ppm) to overcome their metabolic defenses.

From a comparative perspective, spores differ from other dormant forms like cysts or seeds. While seeds maintain higher metabolic activity for growth, spores prioritize survival over immediate revival. This distinction highlights the evolutionary elegance of spores: they sacrifice responsiveness for longevity. For hobbyists or researchers culturing spores, this means patience is key. Reviving spores requires optimal conditions—nutrient-rich media, warmth, and moisture—to trigger metabolic upregulation. For example, *Aspergillus* spores germinate within hours under ideal conditions, showcasing the latent potential of their minimal activity.

In conclusion, spores’ minimal metabolic activity positions them in a gray area between life and dormancy. This activity is not a sign of vitality in the conventional sense but a strategic adaptation for survival. Recognizing this nuance is crucial for fields like microbiology, food safety, and medicine, where spores’ resilience poses both challenges and opportunities. Whether you’re sterilizing equipment or studying microbial life, understanding this metabolic subtlety transforms how we approach these microscopic survivors.

Discovering Reliable Sources for Mushroom Spores: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Survival Mechanisms: How do spores withstand extreme conditions if they’re not dead?

Spores, often mistaken for lifeless entities due to their dormant state, are in fact highly resilient survival machines. Their ability to withstand extreme conditions—heat, radiation, desiccation, and chemicals—stems from a combination of structural and biochemical adaptations. Unlike active cells, spores shut down metabolic processes, reducing vulnerability to environmental stressors. This dormancy is not death but a strategic pause, allowing them to persist for centuries until conditions improve. Understanding these mechanisms reveals the ingenuity of nature’s design for survival.

One key survival mechanism is the spore’s robust outer coating, composed of layers like the exosporium, spore coat, and cortex. These layers act as a protective shield, repelling harsh chemicals and preventing water loss. For instance, the spore coat contains keratin-like proteins, similar to those in human hair and nails, which provide toughness and resistance. Additionally, the cortex layer, rich in dipicolinic acid (DPA), binds calcium ions to form a lattice that stabilizes the spore’s DNA and proteins against heat and radiation. This structural fortification is why spores can survive boiling water or exposure to UV radiation.

Biochemically, spores enter a state of cryptobiosis, where cellular processes are nearly halted. This metabolic shutdown minimizes energy consumption and damage from reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are harmful byproducts of normal metabolism. Spores also produce small, acid-soluble proteins (SASPs) that bind and protect DNA from fragmentation. These proteins act like molecular shields, ensuring genetic integrity even under extreme stress. Such adaptations explain why Bacillus spores, for example, can survive in space or within the harsh environment of hot springs.

Practical applications of spore survival mechanisms are vast. In medicine, understanding spore resilience helps develop sterilization techniques, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes, to ensure complete destruction of pathogens. In biotechnology, spores are used as models for preserving vaccines and enzymes in dry, stable forms. For instance, lyophilized (freeze-dried) vaccines rely on similar principles of desiccation tolerance seen in spores. Even in astrobiology, studying spores provides insights into potential extraterrestrial life forms that could endure extreme planetary conditions.

To harness spore survival mechanisms, consider these tips: for home canning, ensure jars are heated to at least 100°C to kill any bacterial spores; in laboratory settings, use spore-specific disinfectants like hydrogen peroxide or chlorine bleach; and for long-term food storage, opt for dry, low-moisture environments that mimic the conditions spores thrive in. By learning from spores, we not only combat unwanted microbial growth but also innovate in preservation technologies. Their "not dead, just waiting" strategy is a testament to life’s tenacity in the face of adversity.

Shroomish's Spore Move: When and How to Unlock It

You may want to see also

Scientific Definitions: Does the term dead apply to spores, or is it a misnomer?

Spores, often described as dormant or inactive, challenge our understanding of the term "dead." Scientifically, death implies the irreversible cessation of biological functions, yet spores exhibit a state of suspended animation. They lack metabolic activity, do not reproduce, and appear lifeless. However, this dormancy is a survival strategy, not a termination of life. When conditions improve—adequate moisture, temperature, and nutrients—spores germinate, resuming growth and metabolism. Thus, labeling spores as "dead" is a misnomer; they are alive but exist in a quiescent, highly resilient form.

To understand why "dead" is inaccurate, consider the biological definition of life: organisms that grow, reproduce, respond to stimuli, and maintain homeostasis. Spores, while metabolically inactive, retain the capacity to perform these functions under favorable conditions. For example, bacterial endospores can survive extreme environments, including radiation and desiccation, for centuries. Their DNA remains intact, and their cellular machinery is preserved in a protected state. This contrasts with dead cells, which undergo irreversible degradation and lose their ability to function.

A comparative analysis highlights the distinction. Dead cells are nonfunctional and cannot revive, whereas spores are in a reversible state of dormancy. Think of spores as seeds: neither is "dead," but both are in a resting phase, awaiting optimal conditions to activate. This analogy underscores the importance of precise terminology in science. Misapplying "dead" to spores could lead to misconceptions about their nature and potential risks, particularly in fields like microbiology and food safety, where spore survival is critical.

Practically, understanding spore dormancy has significant implications. For instance, in food preservation, heat treatments (e.g., 121°C for 15 minutes in autoclaving) are designed to kill vegetative cells but may not eliminate spores. These survivors can later germinate, causing spoilage or illness. Similarly, in medicine, spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridium difficile* require specific treatments, such as spore-targeting antibiotics or disinfectants. Recognizing spores as alive but dormant ensures effective strategies for their control, emphasizing the need for accurate scientific definitions in applied contexts.

Are Spore's Network Features Still Accessible in 2023?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores are not dead; they are dormant, resilient structures produced by certain organisms like fungi, bacteria, and plants. They can survive harsh conditions and reactivate under favorable environments.

Spores are considered inactive rather than dead. They can be tested for viability using germination assays or staining techniques to determine if they are capable of reactivating and growing.

Spores remain dormant as a survival strategy, waiting for optimal conditions such as moisture, warmth, and nutrients. Once these conditions are met, they can germinate and resume growth.

Spores can be killed through extreme methods like high heat, chemicals, or radiation. However, they are highly resistant and can remain dormant for years or even centuries under the right conditions.