Young mushrooms, particularly those in their early stages of growth, can be especially deceptive when it comes to toxicity. While some species are safe to consume at any age, others may contain harmful toxins that are present even in their juvenile forms. Identifying young mushrooms accurately is challenging, as their smaller size and less developed features can make them resemble both edible and poisonous varieties. This ambiguity underscores the importance of proper knowledge and caution, as consuming toxic mushrooms, regardless of their age, can lead to severe health risks or even fatalities. Therefore, it is crucial to consult expert guidance or avoid foraging altogether unless one is absolutely certain of a mushroom’s safety.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| General Rule | Not all young mushrooms are poisonous, but many toxic species resemble edible ones in their early stages. |

| Common Toxic Species | Amanita (e.g., Death Cap, Destroying Angel), Galerina, Conocybe, and some Cortinarius species. |

| Symptoms of Poisoning | Gastrointestinal distress, liver or kidney damage, neurological symptoms, or even death, depending on the species. |

| Identification Challenges | Young mushrooms often lack distinctive features (e.g., fully developed caps, gills, or spores), making identification difficult. |

| Safe Foraging Practices | Only consume mushrooms that are 100% identified by an expert; avoid young or unfamiliar species. |

| Myth Debunked | "Bright colors mean poisonous" or "animals can safely eat them" are unreliable indicators of toxicity. |

| Expert Consultation | Always consult a mycologist or use reliable field guides when in doubt. |

| Cooking Effect | Cooking does not neutralize toxins in poisonous mushrooms. |

| Prevalence | Approximately 1-2% of mushroom species are deadly, but many more can cause illness. |

| Geographic Variation | Toxicity varies by region; local knowledge is crucial. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Common poisonous species identification

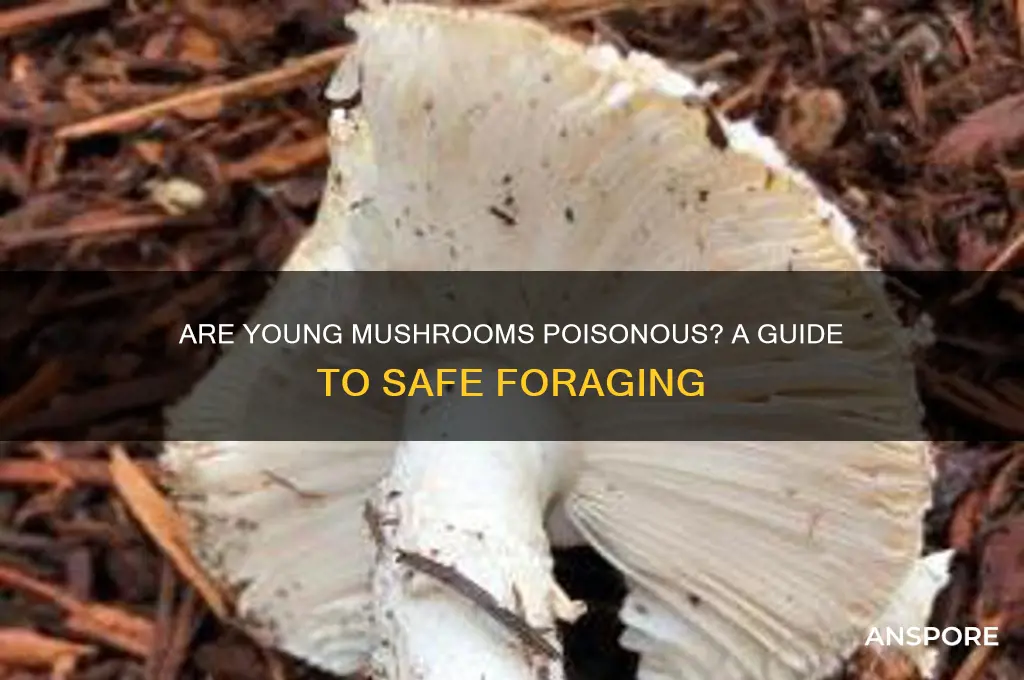

Young mushrooms, often tempting foragers with their vibrant colors and delicate forms, can be deceptively dangerous. Identifying poisonous species is crucial, as many toxic varieties resemble their edible counterparts. For instance, the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) is a notorious example, frequently mistaken for edible paddy straw mushrooms or young puffballs. Its smooth, greenish cap and white gills belie a toxin potent enough to cause liver failure with as little as 50 grams consumed. Similarly, the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) mimics the common button mushroom but contains amatoxins that can be lethal within 24 hours. These examples underscore the importance of precise identification, as even experienced foragers can be misled by superficial similarities.

To avoid misidentification, focus on key features such as spore color, gill attachment, and the presence of a volva (a cup-like structure at the base). For example, the Galerina marginata, often found on decaying wood, has a brown spore print and a rusty-colored cap, distinguishing it from edible honey mushrooms. However, its small size and unassuming appearance make it a frequent culprit in accidental poisonings. Another red flag is the Conocybe filaris, a small, nondescript mushroom with a conical cap that contains the same toxins as the Death Cap. These species highlight the need for meticulous observation, as subtle details often differentiate the deadly from the delectable.

When in doubt, employ a systematic approach to identification. Start by noting the mushroom’s habitat—is it growing on wood, in grass, or near trees? Document its physical characteristics: cap shape, gill spacing, stem texture, and any unusual odors. For instance, the False Morel (*Gyromitra esculenta*) has a brain-like, wrinkled cap and a distinct odor of bleach or ammonia, setting it apart from true morels. Cross-reference these observations with reliable field guides or apps, but remember that technology is not infallible. Always verify findings with multiple sources, and if uncertainty persists, err on the side of caution.

Practical tips can further reduce risk. Avoid foraging after heavy rain, as moisture can alter a mushroom’s appearance. Never consume a mushroom based solely on its age or size, as young specimens of poisonous species are often more deceptive. For example, juvenile Amanitas may lack the fully developed features that aid identification. Additionally, carry a spore print kit to analyze mushroom prints on-site—a brown or black spore print can immediately rule out certain toxic species. Finally, educate yourself through local mycological societies or workshops, as hands-on learning is invaluable for mastering the nuances of mushroom identification.

In conclusion, while the allure of young mushrooms is undeniable, their potential toxicity demands respect and vigilance. By familiarizing yourself with common poisonous species, employing systematic identification methods, and adhering to practical safety tips, you can minimize the risk of accidental poisoning. Remember, the goal is not just to identify mushrooms but to do so with confidence and precision, ensuring that your foraging adventures remain both rewarding and safe.

Ohio's Poisonous Mushrooms: Identifying Deadly Fungi in the Buckeye State

You may want to see also

Symptoms of mushroom poisoning in humans

Mushroom poisoning symptoms in humans can manifest within 20 minutes to several hours after ingestion, depending on the species and amount consumed. The onset of symptoms is often rapid with Amanita phalloides (Death Cap), one of the most toxic mushrooms, causing severe gastrointestinal distress within 6–24 hours. In contrast, psilocybin mushrooms may produce psychological symptoms like hallucinations within 30 minutes, but these are not life-threatening. The variability in onset time underscores the importance of identifying the mushroom type for appropriate medical intervention.

Symptoms of mushroom poisoning fall into distinct syndromes, each linked to specific toxins. The gastrointestinal syndrome, caused by mushrooms like *Clitocybe dealbata*, induces vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain within 30 minutes to 2 hours. The muscarinic syndrome, associated with *Clitocybe* and *Inocybe* species, leads to sweating, salivation, and blurred vision due to muscarine toxin. More severe is the hepatorenal syndrome, caused by amanitin toxins in *Amanita* species, which can result in liver and kidney failure 24–48 hours post-ingestion. Recognizing these syndromes can guide treatment and predict severity.

Children are particularly vulnerable to mushroom poisoning due to their smaller body mass and tendency to ingest unfamiliar objects. Even a small fragment of a toxic mushroom like *Amanita ocreata* can cause severe symptoms in a child. Common signs in children include persistent vomiting, lethargy, and jaundice, which may indicate liver damage. Parents should monitor for these symptoms and seek immediate medical attention, bringing a sample of the mushroom or a photograph for identification if possible.

To mitigate the risk of poisoning, avoid consuming wild mushrooms unless identified by a mycologist. If symptoms occur, activated charcoal may be administered within the first hour to reduce toxin absorption, but it is not a substitute for medical care. In severe cases, hospitalization with supportive care, such as intravenous fluids and, in extreme cases, liver transplantation, may be necessary. Always contact a poison control center or emergency services for guidance, as prompt action can be life-saving.

Are Yellow Mushrooms Poisonous? A Guide to Identifying Toxic Varieties

You may want to see also

Safe mushroom foraging tips for beginners

Young mushrooms can be deceivingly delicate, their small size and vibrant colors often masking a potent toxicity. This makes proper identification crucial for foragers, especially beginners. Many poisonous mushrooms resemble edible varieties in their early stages, making it easy to mistake a deadly Amanita for a tasty chanterelle.

Know Before You Go: Before venturing into the woods, arm yourself with knowledge. Invest in a reputable field guide specific to your region, focusing on both edible and poisonous species. Learn the key characteristics of mushrooms: cap shape and color, gill arrangement, spore print color, stem features, and habitat. Online resources and local mycological societies can be invaluable for learning and connecting with experienced foragers.

Remember, even experienced foragers sometimes make mistakes. Never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identification.

Location, Location, Location: Different mushroom species thrive in specific environments. Chanterelles, for example, often grow in mossy, coniferous forests, while morels favor disturbed areas like burned forests or recently cleared land. Understanding these preferences increases your chances of finding edible varieties and avoids areas where poisonous species are more common.

Observe the surrounding vegetation and soil type – these clues can be as important as the mushroom itself in determining its identity.

The Power of Observation: When you spot a potential candidate, take your time. Examine it closely, noting every detail. Does it have a ring on the stem? Are the gills free or attached to the stem? Does it bruise when touched? These seemingly small details can be the difference between a delicious meal and a dangerous mistake. Take pictures from multiple angles and make notes about the mushroom's characteristics and its environment.

When in Doubt, Throw it Out: If you have any doubts about a mushroom's identity, err on the side of caution and leave it be. Even a small bite of a poisonous mushroom can have severe consequences. Remember, there are no shortcuts to safe foraging. Patience, knowledge, and a healthy dose of skepticism are your best tools for a successful and safe mushroom hunting experience.

Amanita Mushrooms and Dogs: Toxicity Risks and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Differences between young and mature toxic mushrooms

Young mushrooms, often delicate and unassuming, can be deceptively dangerous. While some species are safe at any age, others become more toxic as they mature, and a few are hazardous from the moment they emerge. Understanding the differences between young and mature toxic mushrooms is crucial for foragers and enthusiasts alike. For instance, the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) is notoriously poisonous at all stages, but its youthful resemblance to edible button mushrooms makes it particularly treacherous. In contrast, the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) also retains its toxicity throughout its lifecycle, but its distinct features become more pronounced as it ages, potentially aiding in identification.

One key difference lies in the visibility of identifying features. Young toxic mushrooms often lack the fully developed characteristics that make mature specimens easier to recognize. For example, the Galerina marginata, a highly toxic species, starts as a small, nondescript brown mushroom with a bell-shaped cap. As it matures, its rusty-brown spores and slender stem become more apparent, but by then, its toxic amatoxins are fully potent. Foragers must be especially cautious with young specimens, as their subtle appearance can lead to misidentification. A practical tip: always consult a detailed field guide or expert before consuming any wild mushroom, especially if it’s in its early stages.

Another critical distinction is the concentration of toxins. Some mushrooms, like the False Morel (*Gyromitra esculenta*), contain higher levels of hydrazine toxins when young. These toxins can cause severe gastrointestinal distress and, in extreme cases, organ failure. Proper preparation, such as boiling and discarding the water multiple times, can reduce toxicity, but this method is not foolproof. Mature False Morels may have slightly lower toxin levels, but they remain unsafe without meticulous preparation. Dosage matters here—even a small amount of young False Morel can be harmful, particularly to children or those with compromised immune systems.

From a comparative perspective, the lifecycle of toxic mushrooms highlights the importance of timing in foraging. While some species, like the Jack-O’-Lantern (*Omphalotus olearius*), emit a bioluminescent glow in maturity, their younger forms lack this telltale sign. This mushroom contains illudins, which cause severe cramps and vomiting, regardless of age. However, its glowing feature in maturity can serve as a warning sign, whereas its youthful appearance might go unnoticed. Foragers should avoid any mushroom with a bitter taste or unusual odor, as these are often indicators of toxicity, regardless of the mushroom’s age.

In conclusion, the differences between young and mature toxic mushrooms are nuanced but critical. Young specimens often lack distinguishing features, making them harder to identify, while some species have higher toxin concentrations in their early stages. Always prioritize caution, educate yourself on specific species, and when in doubt, leave it out. The risks of misidentification far outweigh the rewards of a potentially deadly meal.

Are Flat-Top White Mushrooms Poisonous? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

How to test mushrooms for toxicity at home

Young mushrooms, often mistaken for their mature counterparts, can be particularly deceptive in terms of toxicity. While some species are safe at any age, others may contain harmful compounds that are more concentrated in younger specimens. This makes identifying and testing them crucial for foragers and enthusiasts alike. Here’s how to approach testing mushrooms for toxicity at home, balancing caution with practicality.

Observation and Documentation: Begin by carefully examining the mushroom’s physical characteristics—cap shape, gill color, stem texture, and spore print. Document these details with photographs and notes. Cross-reference your findings with reliable field guides or online databases like *Mushroom Observer* or *iNaturalist*. While this step doesn’t confirm toxicity, it narrows down potential species and highlights known poisonous look-alikes. For instance, the young Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) resembles edible button mushrooms but is deadly if ingested.

Chemical Spot Tests: Some mushrooms react to household chemicals, providing clues about their toxicity. For example, apply a drop of household bleach to the cap or stem. If the mushroom turns olive-green, it may belong to the *Cortinarius* genus, some of which are toxic. Similarly, a drop of potassium hydroxide (KOH) can cause color changes in certain species, such as the toxic *Galerina* turning reddish-brown. However, these tests are not definitive and should be used as supplementary tools, not standalone methods.

Animal Testing (Historical Context and Ethical Considerations): Historically, foragers would feed small amounts of mushrooms to animals like cats or dogs to test for toxicity. This method is highly unethical and unreliable, as animals metabolize toxins differently than humans. For instance, cats are unaffected by the poison in *Amanita muscaria*, while it’s hallucinogenic to humans. Modern foragers should avoid this practice entirely, prioritizing ethical and scientific methods instead.

Cultivation and Controlled Environments: If you’re unsure about a wild mushroom, consider cultivating it in a controlled environment. Growing mushrooms from spores or mycelium allows you to observe their development without risking exposure to unknown toxins. Kits for popular species like oyster or shiitake mushrooms are widely available and provide a safe alternative to foraging. This method is particularly useful for beginners or those living in areas with ambiguous mushroom populations.

Consultation and Professional Testing: When in doubt, consult a mycologist or poison control center. Many universities and local mycological societies offer identification services. For a more definitive answer, professional labs can perform toxicity tests, though these can be costly and time-consuming. For instance, the *Amanita* genus contains both deadly and edible species, and lab analysis can distinguish between them by detecting specific toxins like amatoxins.

Testing mushrooms for toxicity at home requires a combination of observation, chemical analysis, and expert consultation. While no single method guarantees safety, a layered approach minimizes risk. Remember, the mantra of mushroom foraging holds true: “There are old foragers, and there are bold foragers, but there are no old, bold foragers.” Always prioritize caution over curiosity.

Are Red Spotted Mushrooms Poisonous? A Comprehensive Guide to Identification

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all young mushrooms are poisonous. However, many toxic mushroom species resemble edible ones in their early stages, making identification difficult. Always consult an expert before consuming wild mushrooms.

Identifying poisonous young mushrooms can be challenging, as they often lack distinctive features found in mature mushrooms. Key signs like color, gills, or spores may not be fully developed. Avoid relying on myths like "poisonous mushrooms taste bitter" or "animals avoid them."

No, it is not safe to eat young mushrooms if you’re unsure of the species. Misidentification can lead to severe poisoning or even death. Always seek guidance from a mycologist or use a reliable field guide before consuming wild mushrooms.