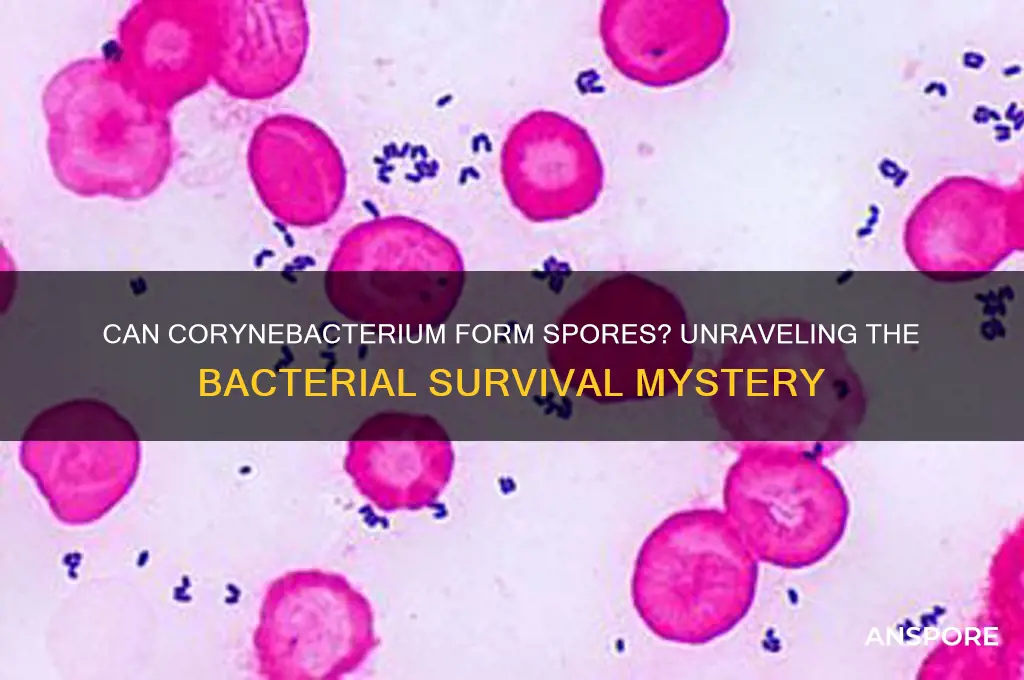

Corynebacterium, a genus of Gram-positive bacteria, is widely recognized for its role in both commensal and pathogenic interactions with humans and animals. While many bacterial species, such as Bacillus and Clostridium, are known for their ability to form spores as a survival mechanism, Corynebacterium is not typically classified as a spore-forming bacterium. Spores are highly resistant structures that allow bacteria to endure harsh environmental conditions, but Corynebacterium species primarily rely on other mechanisms, such as biofilm formation and metabolic adaptability, to survive in diverse environments. Despite some historical debates and rare reports suggesting potential spore-like structures in certain strains, the consensus among microbiologists is that Corynebacterium does not produce true spores. This characteristic distinguishes it from other spore-forming bacteria and influences its behavior in clinical and environmental settings.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spore Formation | Corynebacterium species are non-spore forming bacteria. |

| Cell Wall Structure | Gram-positive, rod-shaped with characteristic club-shaped or V-shaped arrangements. |

| Metabolism | Aerobic or facultatively anaerobic, typically non-motile. |

| Habitat | Commonly found in soil, water, and as part of the normal human microbiota (e.g., skin, respiratory tract). |

| Pathogenicity | Some species are pathogenic, such as Corynebacterium diphtheriae (causes diphtheria). |

| Sporulation Genes | Lack genes associated with spore formation, unlike spore-forming bacteria like Bacillus or Clostridium. |

| Survival Mechanisms | Relies on biofilm formation and persistence in host tissues rather than spore formation for survival in harsh conditions. |

| Taxonomy | Belongs to the phylum Actinomycetota, known for non-spore-forming genera. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Conditions: Specific environmental factors trigger Corynebacterium sporulation, including nutrient depletion and stress

- Genetic Mechanisms: Sporulation genes in Corynebacterium regulate the complex process of spore formation

- Spore Structure: Corynebacterium spores have a unique cell wall composition and protective layers

- Survival Advantages: Spores enhance Corynebacterium's survival in harsh conditions, aiding long-term persistence

- Clinical Relevance: Sporulation impacts Corynebacterium's role in infections and antibiotic resistance mechanisms

Sporulation Conditions: Specific environmental factors trigger Corynebacterium sporulation, including nutrient depletion and stress

Corynebacterium, a genus of Gram-positive bacteria, is not typically known for sporulation, a survival mechanism employed by some bacteria like Bacillus and Clostridium. However, under specific environmental conditions, certain Corynebacterium species can enter a dormant state resembling sporulation. This process is triggered by nutrient depletion and stress, which act as critical signals for the bacterium to initiate survival strategies. Understanding these conditions is essential for both laboratory studies and clinical applications, as they influence the bacterium’s persistence and resistance in various environments.

Analytical Insight: Nutrient depletion, particularly the lack of carbon and nitrogen sources, is a primary trigger for Corynebacterium’s sporulation-like state. When essential nutrients become scarce, the bacterium responds by altering its metabolism and cell structure to conserve energy. For instance, studies have shown that Corynebacterium glutamicum, a species widely used in biotechnology, reduces its growth rate and increases stress resistance proteins under nutrient-limited conditions. This response mimics the early stages of sporulation, though it does not result in a true endospore. The absence of key nutrients acts as a stressor, prompting the bacterium to prioritize survival over replication.

Instructive Guidance: To induce this sporulation-like state in a laboratory setting, researchers can manipulate nutrient availability. A common approach involves culturing Corynebacterium in minimal media with limited glucose (e.g., 0.1% w/v) and ammonium sulfate (e.g., 0.05% w/v). Over time, as these nutrients are depleted, the bacteria will exhibit signs of stress response, such as reduced cell division and increased production of protective proteins. It’s crucial to monitor pH levels, as nutrient depletion can lead to acidification, further stressing the cells. Maintaining a pH of 7.0–7.4 ensures the stress is primarily nutrient-driven rather than pH-induced.

Comparative Perspective: Unlike true spore-formers like Bacillus subtilis, which produce highly resistant endospores, Corynebacterium’s response to stress is less robust. While Bacillus spores can survive extreme conditions such as heat, radiation, and desiccation, Corynebacterium’s dormant state offers limited protection. This distinction highlights the evolutionary divergence in survival strategies between these bacteria. However, Corynebacterium’s ability to enter a dormant state under stress is still significant, as it allows the bacterium to persist in hostile environments, such as those encountered during infection or industrial processes.

Practical Takeaway: For clinicians and researchers, understanding Corynebacterium’s response to nutrient depletion and stress is vital for managing infections and optimizing biotechnological applications. In clinical settings, nutrient-poor environments, such as those found in abscesses or necrotic tissue, may trigger the bacterium’s dormant state, making it more resistant to antibiotics. In biotechnology, controlling sporulation-like conditions can enhance the production of metabolites like amino acids. By manipulating nutrient availability and stress factors, researchers can harness Corynebacterium’s survival mechanisms for both therapeutic and industrial purposes.

Descriptive Example: Imagine a bioreactor where Corynebacterium glutamicum is cultivated to produce glutamate, a key ingredient in food additives. As the glucose concentration drops below 0.05% w/v, the bacteria shift from active growth to a dormant state, reducing their metabolic activity. This transition not only conserves energy but also redirects resources toward glutamate production. By carefully managing nutrient depletion, engineers can maximize yield while minimizing waste. This example illustrates how understanding sporulation conditions can be practically applied to improve efficiency in industrial microbiology.

Using Spore Syringes on Agar Dishes: Techniques and Best Practices

You may want to see also

Genetic Mechanisms: Sporulation genes in Corynebacterium regulate the complex process of spore formation

Corynebacterium, a genus of Gram-positive bacteria, is not typically known for sporulation, a process more commonly associated with Bacillus and Clostridium species. However, recent genetic studies have revealed that certain Corynebacterium strains possess sporulation-like genes, challenging traditional classifications. These genes, while not leading to true endospores, regulate complex processes akin to spore formation, such as cell differentiation and stress resistance. Understanding these genetic mechanisms is crucial for unraveling Corynebacterium's survival strategies and potential biotechnological applications.

Analyzing the sporulation genes in Corynebacterium, researchers have identified homologs to key regulators found in Bacillus subtilis, such as Spo0A and SigH. These genes orchestrate a cascade of events, including DNA protection, cell wall remodeling, and metabolic shifts. For instance, Spo0A in Corynebacterium glutamicum activates the expression of heat-shock proteins and antioxidant enzymes, enhancing survival under oxidative stress. Unlike Bacillus, however, Corynebacterium lacks the genes for spore coat synthesis, resulting in a distinct phenotype. This partial sporulation pathway suggests an evolutionary adaptation to specific environmental pressures rather than a full-fledged spore-forming capability.

To explore these mechanisms experimentally, researchers employ techniques like gene knockout studies and transcriptomic analysis. For example, deleting the sigH gene in Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis reduces its ability to withstand desiccation by 70%, highlighting its role in stress response. Practical tips for lab studies include using defined media with 0.5% glucose to induce sporulation-like conditions and monitoring gene expression via qPCR at 4-hour intervals. Such experiments not only elucidate the function of these genes but also pave the way for engineering Corynebacterium strains with enhanced resilience for industrial applications, such as biofuel production.

Comparatively, while Bacillus spores can survive for decades in harsh conditions, Corynebacterium's sporulation-like process yields cells with limited longevity, typically surviving weeks under stress. This difference underscores the functional divergence of their genetic mechanisms. However, Corynebacterium's ability to rapidly activate stress-response pathways offers unique advantages, such as quicker adaptation to fluctuating environments. By studying these genes, scientists can identify novel targets for antimicrobial development, particularly against pathogenic strains like Corynebacterium diphtheriae, which relies on similar mechanisms for persistence in host tissues.

In conclusion, the sporulation genes in Corynebacterium, though not leading to true spores, regulate a sophisticated process of cell differentiation and stress resistance. These genetic mechanisms provide insights into the bacterium's survival strategies and offer practical applications in biotechnology and medicine. By leveraging this knowledge, researchers can engineer robust strains for industrial use and develop targeted therapies against pathogenic Corynebacterium species. This emerging field bridges the gap between fundamental genetics and applied microbiology, showcasing the versatility of bacterial adaptation.

Are Damp Spores Dangerous? Understanding Health Risks and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Spore Structure: Corynebacterium spores have a unique cell wall composition and protective layers

Corynebacterium, a genus of Gram-positive bacteria, is primarily known for its role in various infections and industrial applications. While it is not traditionally classified as a spore-forming bacterium, recent studies have shed light on its ability to produce spore-like structures under specific conditions. These structures, though not identical to the spores of Bacillus or Clostridium, exhibit unique features, particularly in their cell wall composition and protective layers. Understanding these characteristics is crucial for both medical and biotechnological advancements.

The cell wall of Corynebacterium spores is distinct from that of vegetative cells, featuring a thickened peptidoglycan layer enriched with long-chain mycolic acids. These mycolic acids, typically associated with the genus Mycobacterium, form a waxy outer barrier that enhances resistance to environmental stressors such as desiccation, antibiotics, and immune responses. This unique composition not only provides structural integrity but also contributes to the bacterium’s ability to survive in harsh conditions. For instance, mycolic acids reduce permeability to hydrophobic molecules, making the spore more resilient to disinfectants and antimicrobial agents.

In addition to the cell wall, Corynebacterium spores are encased in multiple protective layers that further enhance their durability. One such layer is the spore coat, a proteinaceous shell that acts as a physical barrier against enzymes, heat, and chemicals. Unlike the highly structured coats of Bacillus spores, Corynebacterium’s coat is less defined but equally effective in shielding the spore’s genetic material. Another critical layer is the exosporium, a loose-fitting outer membrane that may contain glycoproteins and lipids, providing additional protection and aiding in spore dispersal. These layers collectively ensure the spore’s longevity and ability to withstand adverse environments.

From a practical standpoint, the unique spore structure of Corynebacterium has significant implications for infection control and biotechnology. In medical settings, understanding these protective mechanisms can inform the development of more effective sterilization protocols, particularly for surfaces and equipment contaminated with Corynebacterium species. For example, spores’ resistance to common disinfectants like ethanol suggests the need for alternative agents such as chlorine-based solutions or prolonged exposure to heat. In biotechnology, the spore’s robust structure could be harnessed for the production of stable, long-lasting vaccines or enzymes, leveraging its ability to withstand extreme conditions during storage and transport.

In conclusion, while Corynebacterium spores may not conform to the traditional definition of bacterial spores, their unique cell wall composition and protective layers make them a fascinating subject of study. By dissecting these structural features, researchers can unlock new strategies for combating infections and optimizing biotechnological applications. Whether in the clinic or the lab, the spore’s resilience offers both challenges and opportunities that demand further exploration.

Unveiling the Role of Spores in Homeostatic Soil Organisms

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Survival Advantages: Spores enhance Corynebacterium's survival in harsh conditions, aiding long-term persistence

Corynebacterium, a genus of Gram-positive bacteria, is not known to produce spores. This distinction is crucial, as spore formation is a survival mechanism employed by other bacterial genera, such as Bacillus and Clostridium, to endure extreme conditions. However, the absence of spore formation in Corynebacterium does not diminish its ability to persist in harsh environments. Instead, it relies on alternative strategies, such as biofilm formation and resistance to desiccation, to ensure long-term survival. Understanding these mechanisms provides insight into how Corynebacterium thrives in diverse and challenging habitats, from soil to human skin.

To appreciate the survival advantages of spore-forming bacteria, consider the following comparison: spores are akin to bacterial "time capsules," allowing organisms to remain dormant for years, even decades, until conditions improve. For instance, Bacillus anthracis spores can survive in soil for up to 40 years. In contrast, Corynebacterium lacks this capability but compensates through robust cell wall structures and metabolic flexibility. For example, *Corynebacterium glutamicum* can withstand high osmotic stress by accumulating compatible solutes like trehalose, a trait exploited in industrial amino acid production. This adaptability highlights how non-spore-forming bacteria like Corynebacterium achieve persistence without relying on sporulation.

From a practical standpoint, the inability of Corynebacterium to form spores has implications for disinfection and sterilization protocols. Spores of spore-forming bacteria require extreme measures, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes, to ensure inactivation. Non-spore-forming bacteria, including Corynebacterium, are generally more susceptible to standard disinfectants like 70% ethanol or quaternary ammonium compounds. However, their biofilm-forming ability can complicate eradication, particularly in clinical settings. For instance, *Corynebacterium striatum* biofilms on medical devices necessitate rigorous cleaning and disinfection procedures to prevent healthcare-associated infections.

Persuasively, the absence of spore formation in Corynebacterium underscores the importance of targeting its unique survival mechanisms for effective control. While spores pose a significant challenge due to their resilience, Corynebacterium's reliance on biofilms and stress tolerance pathways presents alternative vulnerabilities. Researchers and practitioners can exploit these weaknesses by developing biofilm-disrupting agents or inhibitors of stress response pathways. For example, enzymes like DNase can degrade the extracellular DNA matrix of biofilms, enhancing the efficacy of antimicrobials. Such strategies offer a more nuanced approach to managing Corynebacterium in both environmental and clinical contexts.

In conclusion, while Corynebacterium does not produce spores, its survival strategies are no less remarkable. By focusing on its unique adaptations—such as biofilm formation, osmotic tolerance, and metabolic versatility—we gain a deeper understanding of its persistence in harsh conditions. This knowledge not only informs disinfection practices but also inspires innovative approaches to combat Corynebacterium-related challenges. Whether in industrial settings or healthcare environments, recognizing and addressing these mechanisms is key to managing this resilient bacterial genus effectively.

Are Psilocybe Spores Legal? Exploring the Legal Landscape and Implications

You may want to see also

Clinical Relevance: Sporulation impacts Corynebacterium's role in infections and antibiotic resistance mechanisms

Corynebacterium, a genus of Gram-positive bacteria, is not typically known for sporulation, a survival mechanism employed by other bacteria like Bacillus and Clostridium. However, recent studies suggest that certain Corynebacterium species may exhibit spore-like structures under specific environmental stresses, such as nutrient deprivation or exposure to antibiotics. This phenomenon raises critical questions about its clinical relevance, particularly in the context of infections and antibiotic resistance. Understanding whether and how Corynebacterium can form spores is essential for developing effective treatment strategies, as spores are notoriously resistant to antibiotics, heat, and desiccation.

From an analytical perspective, the potential sporulation of Corynebacterium could explain its persistence in chronic infections, such as those seen in cystic fibrosis patients or immunocompromised individuals. Spores, if formed, could act as a dormant reservoir, allowing the bacteria to survive hostile conditions and re-emerge when the environment becomes favorable. For instance, in cystic fibrosis, the thick mucus in the lungs creates a nutrient-poor environment that might trigger spore-like formation. Clinicians should consider this possibility when treating recurrent infections, as standard antibiotic regimens may fail to eradicate these resilient forms. Prolonged or combination therapy, targeting both active and dormant states, could be more effective in such cases.

Instructively, healthcare providers must remain vigilant for signs of antibiotic resistance linked to sporulation. If Corynebacterium can indeed form spores, this mechanism could contribute to its survival in the presence of antibiotics. For example, vancomycin, a common treatment for Corynebacterium infections, may be less effective against spore-like structures. To combat this, clinicians should consider adjunctive therapies, such as heat treatment or spore-specific antimicrobial agents, in high-risk cases. Additionally, monitoring antibiotic susceptibility patterns in recurrent infections can provide valuable insights into the role of sporulation in resistance.

Persuasively, the clinical implications of Corynebacterium sporulation extend beyond individual patient management to public health concerns. Spores can persist in hospital environments, increasing the risk of nosocomial infections. Enhanced disinfection protocols, particularly in intensive care units and surgical wards, are crucial to prevent transmission. For instance, using spore-specific disinfectants like hydrogen peroxide vapor or chlorine dioxide gas could reduce environmental contamination. Hospitals should also implement strict hand hygiene practices and isolate patients with suspected spore-forming infections to limit spread.

Comparatively, while Corynebacterium’s sporulation capacity is not as well-established as that of Bacillus anthracis, the potential parallels cannot be ignored. B. anthracis spores are infamous for their role in anthrax, a severe and often fatal disease. If Corynebacterium can form similar structures, it could pose a significant threat, especially in immunocompromised populations. Unlike B. anthracis, however, Corynebacterium infections are typically opportunistic, making early detection and intervention critical. Clinicians should be aware of this distinction but remain cautious about the evolving understanding of Corynebacterium’s survival strategies.

In conclusion, the clinical relevance of Corynebacterium sporulation lies in its potential to exacerbate infections and contribute to antibiotic resistance. While research is ongoing, healthcare providers must adapt their approaches to account for this possibility. From adjusting treatment regimens to enhancing infection control measures, a proactive stance is essential. As our understanding of Corynebacterium’s biology deepens, so too must our strategies for managing the infections it causes.

Are Spores and Endospores Identical? Unraveling the Microbial Differences

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, Corynebacterium species are non-spore-forming bacteria. They belong to the group of Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria that do not produce endospores.

Understanding whether Corynebacterium can form spores is crucial for identifying and controlling infections, as spore-forming bacteria are more resistant to environmental stresses and disinfection methods. Since Corynebacterium does not form spores, it is generally less resilient outside the host.

No, there are no known exceptions or variants of Corynebacterium that produce spores or spore-like structures. They consistently lack the genetic and morphological characteristics required for sporulation.