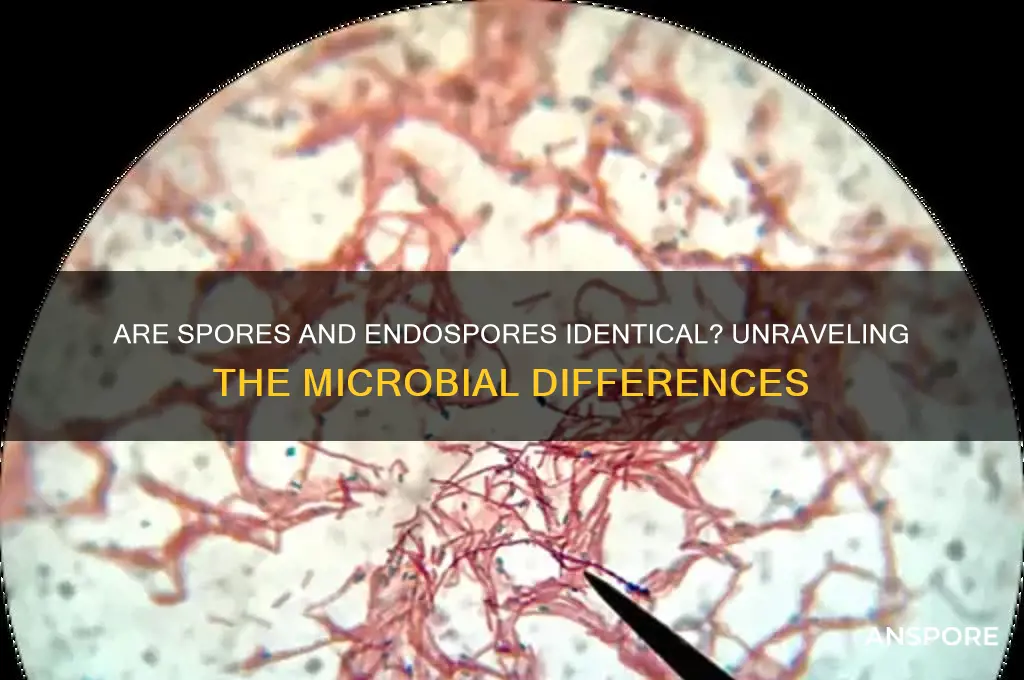

Spores and endospores are often confused due to their similar roles in microbial survival, but they are distinct structures with different characteristics and functions. Spores are reproductive or resistant structures produced by various organisms, including fungi, plants, and some bacteria, primarily for dispersal and reproduction. In contrast, endospores are highly resistant, dormant structures formed exclusively by certain bacterial species, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, as a survival mechanism in harsh environmental conditions. While both serve as protective forms, endospores are more resilient, capable of withstanding extreme temperatures, radiation, and chemicals, whereas spores are generally less durable and primarily function in propagation. Understanding these differences is crucial for distinguishing their biological significance and ecological roles.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition Comparison: Spores are reproductive units; endospores are bacterial survival structures

- Formation Process: Spores develop via meiosis; endospores form within bacterial cells

- Function Difference: Spores aid reproduction; endospores ensure bacterial survival in harsh conditions

- Organism Types: Spores are from fungi, plants; endospores are exclusively bacterial

- Structure Contrast: Spores are cells; endospores are dormant, resistant bacterial forms

Definition Comparison: Spores are reproductive units; endospores are bacterial survival structures

Spores and endospores, though often conflated, serve fundamentally different biological purposes. Spores are primarily reproductive units produced by plants, fungi, and some protozoa. These microscopic structures are designed for dispersal and germination, allowing organisms to propagate in new environments. For instance, fern spores can travel on air currents to colonize distant areas, while fungal spores like those of mushrooms rely on wind or water for distribution. In contrast, endospores are not reproductive but rather protective. Produced exclusively by certain bacteria, such as *Clostridium* and *Bacillus*, endospores are dormant, highly resistant structures that enable bacteria to survive extreme conditions like heat, radiation, and desiccation. This distinction highlights their divergent roles: spores facilitate life continuation through reproduction, while endospores ensure bacterial survival during adversity.

To illustrate the difference, consider a practical scenario: a gardener uses heat to sterilize soil before planting. While fungal spores in the soil might be destroyed, bacterial endospores could persist, only reactivating when conditions improve. This resilience is due to the endospore’s thick, multi-layered structure, which includes a spore coat and cortex that protect the bacterial DNA. Spores, however, lack such extreme durability because their function is not survival but propagation. For example, pollen grains (a type of spore) are lightweight and fragile, optimized for wind dispersal rather than endurance. Understanding this difference is crucial in fields like agriculture, medicine, and environmental science, where managing microbial life and plant reproduction are key concerns.

From an analytical perspective, the confusion between spores and endospores often stems from their shared microscopic size and environmental dispersal. However, their formation processes reveal their distinct purposes. Spores are typically produced through meiosis or asexual budding, depending on the organism, and are released in large quantities to increase the odds of successful germination. Endospores, on the other hand, are formed within a bacterial cell through a complex process called sporulation, which involves the replication of DNA and the assembly of protective layers. This energy-intensive process is triggered by nutrient depletion or other stressors, underscoring its role as a survival mechanism rather than a reproductive strategy.

For those working in microbiology or related fields, distinguishing between spores and endospores has practical implications. For instance, in food preservation, understanding that endospores can withstand boiling temperatures explains why certain bacteria, like *Clostridium botulinum*, pose risks in canned foods. To eliminate endospores, specific conditions—such as temperatures above 121°C (250°F) for 15–30 minutes in an autoclave—are required. In contrast, plant spores are generally less resilient and can be managed with less extreme measures, such as fungicides or physical barriers. This knowledge informs protocols for sterilization, contamination control, and disease prevention, ensuring both safety and efficiency in various applications.

In summary, while spores and endospores share superficial similarities, their functions and structures diverge sharply. Spores are reproductive tools, evolved for dispersal and germination, whereas endospores are bacterial survival mechanisms, engineered to withstand harsh conditions. Recognizing this difference not only clarifies biological concepts but also guides practical decisions in industries ranging from healthcare to horticulture. Whether sterilizing equipment, preserving food, or cultivating plants, understanding the unique roles of spores and endospores is essential for achieving desired outcomes and mitigating risks.

Endospores vs. Fungal Spores: Which Survives Harsh Conditions Better?

You may want to see also

Formation Process: Spores develop via meiosis; endospores form within bacterial cells

Spores and endospores, though often conflated, differ fundamentally in their formation processes. Spores, typically associated with fungi, plants, and some protozoa, develop through meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, producing genetically diverse offspring. This process is essential for sexual reproduction and ensures variability in the next generation. In contrast, endospores are formed within bacterial cells as a survival mechanism in response to harsh environmental conditions. Unlike spores, endospores do not involve meiosis; instead, they are produced through a complex series of steps involving DNA replication and the formation of a protective shell within the bacterial cell itself.

To understand the formation of spores, consider the life cycle of a fern. When a fern plant reaches maturity, it produces sporangia, structures that contain spore mother cells. These cells undergo meiosis, dividing twice to produce four haploid spores. Each spore, when released and under favorable conditions, germinates into a gametophyte, which eventually develops into a new fern plant. This process highlights the role of meiosis in spore formation, ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability. For gardeners cultivating ferns, understanding this cycle is crucial for successful propagation, as spores require specific humidity and light conditions to thrive.

Endospores, on the other hand, are formed through a process called sporulation, which is unique to certain bacterial species like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*. When nutrients become scarce or environmental conditions turn hostile, a bacterial cell initiates sporulation by replicating its DNA and enclosing it within a protective layer called the forespore. This forespore matures into an endospore, which is highly resistant to heat, radiation, and chemicals. For instance, endospores of *Clostridium botulinum* can survive boiling water, making proper canning techniques essential to prevent foodborne illness. Unlike spores, endospores do not involve genetic recombination, as they are essentially dormant copies of the original bacterial cell.

The distinction in formation processes has practical implications. In microbiology labs, distinguishing between spores and endospores is critical for sterilization protocols. While spores may require specific conditions to be eradicated, endospores demand more rigorous methods, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes. For home canners, understanding that endospores can survive boiling water underscores the importance of using a pressure canner for low-acid foods. Conversely, gardeners dealing with fungal spores might employ fungicides or adjust environmental conditions to inhibit spore germination, a strategy irrelevant to endospores.

In summary, while both spores and endospores serve as survival mechanisms, their formation processes reflect their distinct origins and functions. Spores, born of meiosis, drive genetic diversity and reproduction in eukaryotic organisms, whereas endospores, formed within bacterial cells, provide unparalleled resilience without genetic variation. Recognizing these differences is not just an academic exercise but a practical necessity for fields ranging from microbiology to horticulture, ensuring effective strategies for both preservation and eradication.

Are Fungal Spores Dangerous? Unveiling Health Risks and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Function Difference: Spores aid reproduction; endospores ensure bacterial survival in harsh conditions

Spores and endospores, though often conflated, serve distinct biological purposes. Spores are primarily reproductive structures produced by plants, fungi, and some protists. Their core function is to facilitate dispersal and colonization of new environments. For instance, fern spores, microscopic and lightweight, are carried by wind to distant locations where they germinate into new plants. Similarly, fungal spores, such as those of mushrooms, are released in vast quantities to ensure at least a few land in suitable habitats for growth. This reproductive strategy maximizes species survival by spreading genetic material widely.

Endospores, in contrast, are not reproductive tools but survival mechanisms unique to certain bacteria. Formed in response to nutrient depletion, desiccation, or extreme temperatures, endospores are highly resistant structures that safeguard bacterial DNA. Unlike spores, which are designed to grow into new organisms, endospores remain dormant until conditions improve. For example, *Clostridium botulinum* produces endospores that can survive boiling water, making them a concern in food preservation. This ability to endure harsh conditions highlights their role as a bacterial "last resort" rather than a means of reproduction.

The structural differences between spores and endospores further underscore their functional divergence. Spores are often multicellular and contain stored nutrients to support initial growth upon germination. Endospores, however, are single-celled and stripped of unnecessary components, consisting primarily of DNA and a protective coat. This minimalist design allows endospores to withstand radiation, extreme pH, and even the vacuum of space, as demonstrated in experiments on the International Space Station. Such resilience is unnecessary for spores, which prioritize growth and dispersal over survival in extreme environments.

Practical implications of these differences are significant. In agriculture, understanding spore dispersal helps optimize crop pollination and pest control. For instance, timing fungicide applications to disrupt fungal spore release can prevent crop diseases. In contrast, knowledge of endospores is critical in medical and industrial sterilization processes. Autoclaves, which use steam under pressure, are effective against endospores because they require temperatures above 121°C and prolonged exposure to ensure destruction. Misidentifying endospores as spores could lead to inadequate sterilization, risking contamination in labs or healthcare settings.

In summary, while both spores and endospores are survival adaptations, their functions diverge sharply. Spores drive reproduction and colonization, ensuring species propagation across environments. Endospores, however, are bacterial survival pods, enabling endurance in conditions that would destroy active cells. Recognizing this distinction is essential for fields ranging from ecology to microbiology, where precise interventions depend on understanding these structures' unique roles.

Understanding Spore Production: Locations and Processes in Fungi and Plants

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Organism Types: Spores are from fungi, plants; endospores are exclusively bacterial

Spores and endospores, though often conflated, originate from distinct biological kingdoms. Spores are reproductive or resistant structures produced by fungi and plants, while endospores are exclusively formed by certain bacteria. This fundamental difference in organism type underscores their unique roles in survival and propagation. Fungi, such as mushrooms, release spores to reproduce, dispersing them through air or water to colonize new environments. Similarly, plants like ferns and mosses rely on spores for asexual reproduction, ensuring genetic continuity without the need for seeds. In contrast, endospores are not reproductive but rather protective mechanisms. Bacteria like *Clostridium* and *Bacillus* form endospores to withstand extreme conditions, such as heat, radiation, or desiccation, allowing them to persist in hostile environments until conditions improve.

Understanding the organism types behind spores and endospores is crucial for practical applications. For instance, fungal spores are a common allergen, affecting up to 30% of the global population. Identifying spore-producing fungi in indoor environments, such as *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, can guide remediation efforts to improve air quality. Plant spores, on the other hand, are essential in horticulture and ecology. For example, orchid growers use spore cultivation techniques to propagate rare species, while ecologists study fern spores to track forest health. Endospores, however, are primarily relevant in medical and industrial contexts. Sterilization protocols, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes, are designed to destroy bacterial endospores, ensuring equipment and environments are free from pathogens like *Clostridium botulinum*.

The distinction between spores and endospores also highlights their evolutionary strategies. Fungi and plants use spores as a primary means of dispersal and reproduction, often producing them in vast quantities to increase the likelihood of successful colonization. For example, a single mushroom can release billions of spores in a single day. Endospores, however, are a survival mechanism rather than a reproductive one. Bacteria form endospores in response to nutrient depletion or environmental stress, halting metabolic activity until conditions become favorable again. This dormancy can last for decades, as evidenced by endospores revived from ancient sediments. While spores are about proliferation, endospores are about persistence.

Practical tips for managing spores and endospores vary depending on their source. To reduce fungal spore exposure, maintain indoor humidity below 50% and regularly clean air filters. For plant spores, gardeners can use fine mesh screens to protect seedlings from unwanted contamination. In laboratory settings, handling bacterial endospores requires stringent protocols, including the use of biosafety cabinets and heat-resistant disinfectants. Understanding these organism types not only clarifies their differences but also empowers targeted interventions, whether in healthcare, agriculture, or environmental management. By recognizing their origins and functions, we can better navigate the challenges posed by these microscopic structures.

Effective Ways to Eliminate Airborne Mold Spores in Your Home

You may want to see also

Structure Contrast: Spores are cells; endospores are dormant, resistant bacterial forms

Spores and endospores, though often conflated, differ fundamentally in their biological nature and function. Spores are reproductive or resistant cells produced by plants, fungi, and some protozoa, designed to disperse and germinate under favorable conditions. In contrast, endospores are not cells but rather dormant, highly resistant structures formed by certain bacteria as a survival mechanism. This distinction is critical: spores are living entities capable of growth and division, while endospores are metabolically inactive forms that can withstand extreme conditions like heat, radiation, and desiccation.

To illustrate, consider the lifecycle of a fern versus a bacterium like *Clostridium botulinum*. Ferns release spores that, when landing in a suitable environment, grow into new plants. These spores are cells with genetic material and the capacity for photosynthesis. Endospores, however, are not reproductive units but protective shells containing bacterial DNA and essential enzymes. For instance, *C. botulinum* forms endospores that can survive boiling water (100°C) for hours, a feat no plant or fungal spore can match. This resilience is due to the endospore’s multilayered structure, including a cortex rich in dipicolinic acid, which binds calcium ions to stabilize the DNA.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this structural contrast is vital in fields like food safety and medicine. Endospores of pathogens such as *Bacillus anthracis* (causative agent of anthrax) can persist in soil for decades, posing risks to humans and animals. To eliminate them, sterilization methods like autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes are required, far exceeding the conditions needed to kill vegetative bacterial cells or plant spores. In contrast, fungal spores in food (e.g., mold on bread) are typically inactivated by pasteurization (72°C for 15 seconds), a less stringent process.

A comparative analysis reveals why endospores are not considered cells. Unlike spores, which retain metabolic activity and can germinate directly, endospores must first revert to vegetative bacterial cells before growth can occur. This process, called germination, is triggered by specific nutrients and environmental cues. For example, in the food industry, the presence of endospores in canned goods can lead to spoilage or botulism if not properly sterilized. Here, the endospore’s non-cellular, ultra-resistant nature necessitates precise control measures, such as pH adjustments (below 4.6) or the addition of preservatives like nitrites.

In summary, while both spores and endospores serve as survival mechanisms, their structural and functional differences dictate distinct approaches to management and eradication. Spores, as living cells, are more susceptible to environmental controls, whereas endospores require extreme measures due to their dormant, non-cellular architecture. Recognizing this contrast is essential for applications ranging from agriculture to healthcare, ensuring that strategies are tailored to the unique challenges each presents.

Understanding Spores: Their Role, Survival Mechanisms, and Ecological Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, spores and endospores are not the same. Spores are reproductive or resistant structures produced by various organisms, such as fungi, plants, and some bacteria, to survive harsh conditions or disperse. Endospores, on the other hand, are highly resistant dormant structures produced by certain bacteria, primarily within the Firmicutes phylum, to survive extreme environmental conditions.

No, not all bacteria produce both. Only specific bacterial species, such as those in the genus *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, produce endospores. Spores, in a broader sense, are produced by various bacteria, fungi, and plants, but endospores are exclusive to certain bacterial groups.

The main purpose of both spores and endospores is survival in unfavorable conditions. Spores allow organisms to disperse or persist in harsh environments, while endospores specifically enable bacteria to withstand extreme conditions like heat, radiation, and desiccation.

Yes, endospores can be considered a specialized type of spore. They are a unique form of bacterial spore designed for extreme resistance, but they differ from other spores in structure, function, and the organisms that produce them.