Tetanus is a severe and potentially life-threatening bacterial infection caused by *Clostridium tetani*, a gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium. One of the most remarkable features of this pathogen is its ability to exist in a dormant spore form, which allows it to survive in harsh environmental conditions, such as soil, dust, and animal feces, for extended periods. When these spores enter the body through wounds or breaks in the skin, they germinate into active bacteria, producing a potent neurotoxin called tetanospasmin. This toxin interferes with nerve signaling, leading to painful muscle contractions, stiffness, and, in severe cases, respiratory failure. Understanding the spore-forming nature of *C. tetani* is crucial for prevention strategies, including proper wound care and vaccination, to mitigate the risk of tetanus infection.

Explore related products

$11.99 $16.99

What You'll Learn

- Clostridium tetani: The bacterium responsible for tetanus, thrives in soil, dust, and animal feces

- Spores survive harsh conditions: Heat, cold, and chemicals, remaining dormant until favorable conditions

- Wound entry: Spores penetrate deep tissues through cuts, burns, or punctures, initiating infection

- Toxin production: Spores germinate, producing tetanospasmin, a potent neurotoxin causing muscle stiffness

- Prevention: Vaccination and wound care are key to avoiding tetanus infection and complications

Clostridium tetani: The bacterium responsible for tetanus, thrives in soil, dust, and animal feces

Clostridium tetani, the bacterium behind tetanus, is a master of survival, thriving in environments as mundane as soil, dust, and animal feces. This rod-shaped, gram-positive anaerobe produces spores that are remarkably resilient, capable of enduring extreme conditions such as heat, cold, and desiccation. These spores serve as the bacterium’s dormant form, allowing it to persist in the environment for years, waiting for the right conditions to reactivate and cause infection. Unlike many pathogens that require specific hosts, *C. tetani*’s ability to exist in spore form makes it ubiquitous, posing a constant threat in agricultural settings, construction sites, and even home gardens.

Consider the practical implications of this bacterium’s habitat. For instance, a puncture wound from a rusty nail or a deep cut exposed to soil can introduce *C. tetani* spores into the body. Once inside, the spores germinate in the oxygen-poor environment of deep tissues, producing a potent neurotoxin called tetanospasmin. This toxin travels through the bloodstream to the nervous system, causing muscle stiffness and spasms, the hallmark symptoms of tetanus. The risk is particularly high in individuals who haven’t received a tetanus vaccination or whose immunity has waned over time. For adults, a tetanus booster is recommended every 10 years, while children should follow the CDC’s immunization schedule, which includes doses at 2, 4, 6, and 15–18 months, followed by boosters at 4–6 years and 11–12 years.

To mitigate the risk of tetanus, proactive measures are essential. Clean any wound thoroughly with soap and water, removing dirt and debris, and seek medical attention for deep or puncture wounds, especially if they’ve been exposed to soil or manure. If you’re unsure of your vaccination status, consult a healthcare provider immediately, as a booster may be necessary. For high-risk injuries, such as those involving metal or animal bites, a tetanus shot within 48 hours can prevent spore germination and toxin production. Additionally, wearing protective gear in environments where *C. tetani* thrives—such as gloves while gardening or sturdy shoes in rural areas—can reduce exposure.

Comparing *C. tetani* to other spore-forming pathogens highlights its unique danger. Unlike *Bacillus anthracis*, which causes anthrax and is primarily associated with livestock, *C. tetani*’s presence in everyday environments makes it a more pervasive threat. While anthrax spores are often linked to bioterrorism or occupational hazards, tetanus spores are a natural component of the ecosystem, requiring no special circumstances to encounter. This distinction underscores the importance of universal precautions, such as vaccination and wound care, rather than targeted interventions.

In conclusion, understanding *C. tetani*’s resilience and habitat is key to preventing tetanus. Its ability to form spores and persist in soil, dust, and animal feces makes it a silent but persistent danger. By staying up-to-date on vaccinations, practicing proper wound care, and taking precautions in high-risk environments, individuals can significantly reduce their risk of infection. Tetanus may be rare in developed countries, but its severity—with a fatality rate of up to 10% even with treatment—demands vigilance. Awareness and action are the best defenses against this ancient bacterium’s modern threat.

Beyond Fungi: Exploring the Diverse World of Spore-Producing Organisms

You may want to see also

Spores survive harsh conditions: Heat, cold, and chemicals, remaining dormant until favorable conditions

Clostridium tetani, the bacterium responsible for tetanus, is a master of survival. Its secret weapon? The ability to form spores, incredibly resilient structures that can withstand conditions that would destroy most life forms. These spores are like microscopic time capsules, biding their time until the environment becomes conducive to growth and replication.

Imagine a desert, scorching hot during the day and freezing cold at night. This is the kind of extreme environment C. tetani spores can endure. They can survive temperatures ranging from below freezing to well above boiling point. Even exposure to harsh chemicals, including many disinfectants, fails to eliminate them. This remarkable resistance allows them to persist in soil, dust, and even on rusty objects for years, silently waiting for an opportunity to strike.

This survival strategy is crucial for the bacterium's lifecycle. Unlike many bacteria that thrive in specific, often limited environments, C. tetani spores can disperse widely, increasing their chances of encountering a suitable host. Once inside a wound, the warm, oxygen-deprived environment triggers the spore to germinate, transforming into its active, toxin-producing form. This toxin, tetanospasmin, is what causes the painful muscle contractions characteristic of tetanus.

Understanding the resilience of C. tetani spores highlights the importance of proper wound care. Even seemingly minor injuries, especially those contaminated with soil or dirt, can provide an entry point for these dormant survivors. Thorough cleaning of wounds with soap and water, followed by application of an antiseptic, significantly reduces the risk of tetanus.

For maximum protection, vaccination is key. The tetanus vaccine, often combined with diphtheria and pertussis vaccines (DTaP or Tdap), stimulates the body's immune system to produce antibodies against the tetanus toxin. This means that even if spores manage to germinate, the body is prepared to neutralize the toxin before it can cause harm. Remember, while spores may be incredibly resilient, we have the tools to prevent them from causing tetanus. Regular vaccination and proper wound care are our best defenses against this potentially deadly disease.

Understanding Spore Plants: A Beginner's Guide to Their Unique Life Cycle

You may want to see also

Wound entry: Spores penetrate deep tissues through cuts, burns, or punctures, initiating infection

Tetanus spores, dormant yet resilient, lie in wait for the perfect opportunity to strike—a breach in the body’s armor. Cuts, burns, or punctures provide the gateway, allowing these microscopic invaders to penetrate deep tissues where they transform into their active, toxin-producing form. This transformation is not immediate; it requires an anaerobic environment, often found in necrotic tissue or deep wounds with poor blood supply. Once activated, the bacteria release tetanospasmin, a potent neurotoxin that wreaks havoc on the nervous system, leading to the characteristic muscle stiffness and spasms of tetanus. Understanding this entry mechanism underscores the urgency of proper wound care, as even minor injuries can become life-threatening if contaminated with *Clostridium tetani* spores.

Consider a scenario: a gardener pricks their finger on a rusty nail. The nail, embedded in soil rich with organic matter, is a prime carrier of tetanus spores. If the wound is deep and not thoroughly cleaned, spores can evade the body’s initial defenses and settle into the oxygen-deprived environment they need to thrive. Within days, the toxin begins to interfere with nerve signaling, causing jaw stiffness, difficulty swallowing, and eventually, full-body rigidity. This progression highlights why immediate wound cleaning with soap and water, followed by professional medical evaluation, is critical. For high-risk wounds, a tetanus booster shot may be necessary, especially if more than five years have passed since the last vaccination.

The risk of spore entry is not limited to dramatic injuries like puncture wounds. Even minor burns or superficial cuts can provide an entry point if conditions are right. For instance, a child scraping their knee while playing outdoors might not seem alarming, but if the wound is exposed to spore-laden dirt and left untreated, infection can take hold. Parents and caregivers should be vigilant, ensuring wounds are cleaned promptly and monitored for signs of redness, swelling, or discharge. In burn cases, the damaged skin creates an ideal environment for spore germination, making it essential to apply sterile dressings and seek medical attention for anything beyond a minor first-degree burn.

Prevention is far simpler than treatment. Tetanus vaccination, part of the standard DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis) series for children and Tdap/Td boosters for adults, provides robust immunity. However, immunity wanes over time, making regular boosters crucial. For those unsure of their vaccination status, a simple blood test can check tetanus antibody levels. In high-risk situations, such as agricultural work or travel to areas with poor sanitation, carrying a first-aid kit with antiseptic wipes and knowing the location of the nearest medical facility can be lifesaving. The lesson is clear: tetanus spores are ubiquitous, but with knowledge and preparedness, their ability to cause harm can be significantly reduced.

Exploring Soridium: Unveiling the Presence of Fungus Spores Within

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Toxin production: Spores germinate, producing tetanospasmin, a potent neurotoxin causing muscle stiffness

Clostridium tetani, the bacterium responsible for tetanus, is a master of survival. Its ability to form spores allows it to endure harsh conditions, lying dormant in soil, dust, and even rust, waiting for the opportunity to strike. When these spores enter the body through a wound, they awaken, transforming into their active, toxin-producing form. This transformation marks the beginning of a potentially deadly process.

The germination of spores is a critical step in the pathogenesis of tetanus. Once inside a suitable environment, such as a deep puncture wound with limited oxygen, the spores sense the change in conditions and begin to grow. This growth is not merely a resumption of bacterial life; it is a calculated shift towards toxin production. The bacterium starts synthesizing tetanospasmin, a neurotoxin so potent that a mere 2.5 nanograms per kilogram of body weight can be lethal to humans. This toxin is the true culprit behind the symptoms of tetanus, particularly the excruciating muscle stiffness that characterizes the disease.

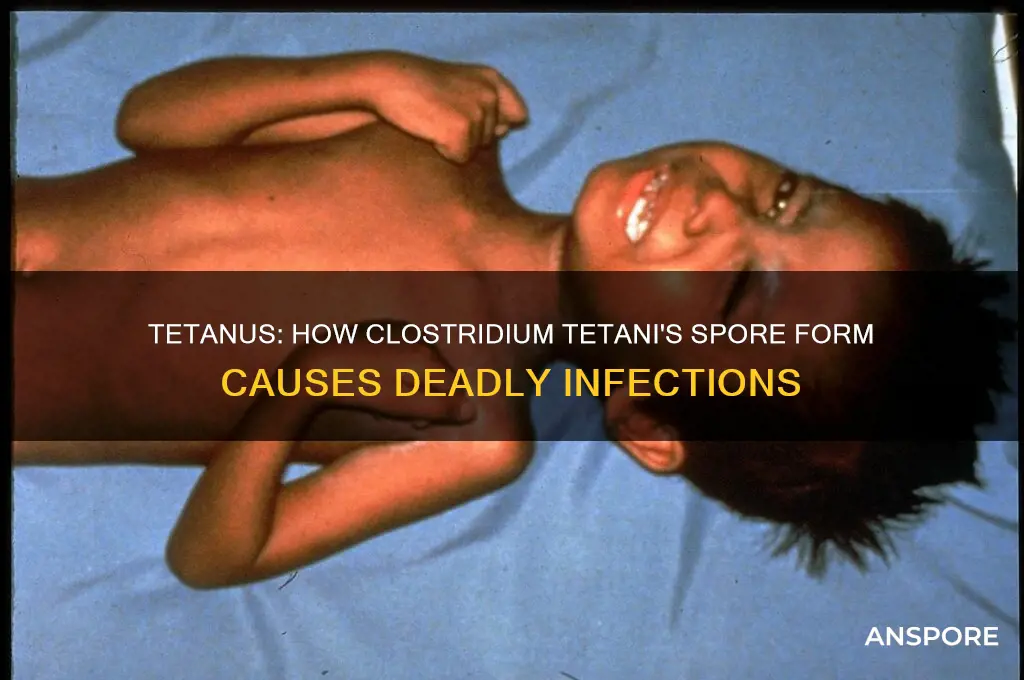

Tetanospasmin acts by interfering with the normal communication between nerves and muscles. It travels through the bloodstream and binds to nerve endings, blocking the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters like glycine and GABA. These neurotransmitters are essential for regulating muscle tone and preventing overactivity. Without them, muscles are constantly stimulated, leading to rigidity and spasms. The most dramatic example is the "lockjaw" symptom, where the masseter muscles of the jaw tighten, making it impossible to open the mouth. However, the toxin’s effects are not limited to the jaw; it can cause widespread muscle stiffness, including in the abdomen, back, and limbs, leading to severe pain and difficulty breathing.

Preventing tetanus hinges on understanding this toxin production process. Vaccination with the tetanus toxoid is the most effective measure, as it primes the immune system to neutralize tetanospasmin before it can cause harm. For those who suffer a wound in a high-risk environment, prompt cleaning and medical attention are crucial. If there’s any doubt about vaccination status, a booster shot should be administered immediately. Additionally, keeping wounds clean and free of foreign debris can reduce the likelihood of spore germination. For deep or dirty wounds, healthcare providers may also prescribe antibiotics to eliminate any bacteria present, though this is secondary to the toxin’s neutralization.

In summary, the germination of *Clostridium tetani* spores and the subsequent production of tetanospasmin are central to the development of tetanus. This toxin’s ability to disrupt nerve-muscle communication results in the hallmark muscle stiffness and spasms. By focusing on prevention through vaccination and proper wound care, the risk of this devastating disease can be significantly reduced. Understanding the mechanics of toxin production not only highlights the bacterium’s ingenuity but also underscores the importance of proactive measures to combat it.

Can Asteroids Collide with Planets in Spore? Exploring the Possibility

You may want to see also

Prevention: Vaccination and wound care are key to avoiding tetanus infection and complications

Tetanus, caused by the bacterium *Clostridium tetani*, is a serious and potentially fatal disease that can be prevented through proactive measures. The bacterium exists in spore form, which allows it to survive in soil, dust, and animal feces for years, making it nearly impossible to eradicate from the environment. However, the good news is that tetanus is entirely preventable through vaccination and proper wound care. These two strategies form the cornerstone of protection against this disease, ensuring that the spores, even if they enter the body, do not cause infection.

Vaccination is the most effective way to prevent tetanus. The tetanus toxoid vaccine, often given in combination with diphtheria and pertussis (DTaP or Tdap), provides long-lasting immunity. For children, the CDC recommends a series of five DTaP shots, starting at 2 months of age, followed by a Tdap booster at 11 or 12 years. Adults should receive a Tdap shot once, followed by a Td (tetanus and diphtheria) booster every 10 years. If you suffer a deep or dirty wound and your last tetanus shot was more than 5 years ago, a booster may be necessary to ensure adequate protection. Adhering to this schedule is crucial, as immunity wanes over time, leaving individuals vulnerable to infection.

Proper wound care is equally vital in preventing tetanus, especially for injuries that expose deep tissues to soil or debris. Clean all wounds immediately with soap and water, removing any foreign material. Apply an antiseptic to reduce the risk of bacterial growth. For severe or contaminated wounds, seek medical attention promptly, as a healthcare provider may recommend a tetanus booster or administer tetanus immunoglobulin (TIG) to neutralize the toxin. Even minor cuts or punctures should not be ignored, as *C. tetani* spores can enter through the smallest openings in the skin. Vigilance in wound management is a simple yet powerful tool in preventing tetanus.

Comparing vaccination and wound care highlights their complementary roles in tetanus prevention. Vaccination acts as a shield, preparing the immune system to neutralize the toxin if exposed, while wound care acts as a barrier, reducing the likelihood of spore entry. Together, they create a robust defense against infection. For instance, a vaccinated individual who promptly cleans and treats a wound is far less likely to develop tetanus than someone who neglects either measure. This dual approach underscores the importance of both proactive and reactive strategies in disease prevention.

In practical terms, preventing tetanus requires a combination of awareness and action. Keep track of your vaccination status and ensure you and your family are up to date on tetanus shots. Educate yourself on proper wound care techniques and have a well-stocked first aid kit at home. For travelers or outdoor enthusiasts, understanding the risks associated with soil-contaminated injuries is essential. By integrating vaccination and wound care into your health routine, you can effectively safeguard against tetanus, turning a potentially deadly threat into a manageable risk.

Unveiling the Origins: Where Do Mold Spores Come From?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Tetanus is a serious bacterial infection caused by the bacterium Clostridium tetani, which can exist in the spore form and is commonly found in soil, dust, and animal feces. The infection occurs when the spores enter the body through a wound or cut, producing a powerful toxin that affects the nervous system.

Yes, Clostridium tetani can exist in the spore form, which is highly resistant to heat, cold, and many disinfectants, allowing it to survive in harsh environments for extended periods. This makes it difficult to eradicate the bacteria from contaminated areas.

When the spore form of Clostridium tetani enters a deep wound or cut, it can germinate into its active form, producing a potent neurotoxin called tetanospasmin. This toxin interferes with the normal functioning of the nervous system, leading to muscle stiffness, spasms, and potentially life-threatening complications.

Yes, tetanus can be prevented through vaccination with the tetanus toxoid vaccine, which helps the body develop immunity to the toxin produced by Clostridium tetani. Additionally, proper wound care, including cleaning and dressing wounds, can reduce the risk of infection. If a wound is suspected to be contaminated with tetanus spores, prompt medical attention and administration of tetanus immunoglobulin may be necessary to prevent the onset of tetanus.