Spore plants, also known as pteridophytes, are a diverse group of vascular plants that reproduce through spores rather than seeds. Unlike flowering plants, which rely on seeds for propagation, spore plants release tiny, single-celled spores that develop into new individuals under favorable conditions. This group includes ferns, mosses, liverworts, and horsetails, each adapted to thrive in various environments, from moist forests to arid landscapes. Their life cycle involves an alternation of generations, where the plant alternates between a spore-producing stage (sporophyte) and a gamete-producing stage (gametophyte). Spore plants play a crucial role in ecosystems, contributing to soil stability, water retention, and biodiversity, while also offering insights into the evolutionary history of plant life on Earth.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A spore plant, also known as a pteridophyte or non-seed vascular plant, is a type of plant that reproduces via spores rather than seeds. |

| Reproduction | Asexual reproduction through spores (haploid, single-celled structures) produced in sporangia. |

| Life Cycle | Alternation of generations: sporophyte (diploid) phase alternates with gametophyte (haploid) phase. |

| Examples | Ferns, mosses, liverworts, horsetails, and lycophytes. |

| Vascular System | Most spore plants have a vascular system (xylem and phloem) for water and nutrient transport, except for bryophytes (mosses, liverworts, and hornworts). |

| Roots | True roots are present in vascular spore plants (e.g., ferns), while bryophytes have rhizoids for anchorage and absorption. |

| Leaves | Microphylls (small, simple leaves) in lycophytes and euphylls (large, complex leaves) in ferns and seed plants. |

| Habitat | Typically found in moist, shaded environments to prevent spore desiccation. |

| Evolution | Among the earliest land plants, appearing over 400 million years ago. |

| Size | Ranges from small mosses (a few millimeters) to large tree ferns (up to 20 meters). |

| Ecological Role | Important in nutrient cycling, soil stabilization, and providing habitat for other organisms. |

| Adaptations | Spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind or water; gametophytes are often dependent on moisture for fertilization. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation: Spores develop in sporangia, reproductive structures on plants like ferns and mosses

- Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, or animals carry spores to new habitats for germination

- Germination Process: Spores activate under favorable conditions, growing into gametophytes

- Life Cycle Types: Alternation of generations between sporophyte and gametophyte phases

- Examples of Plants: Ferns, mosses, liverworts, and horsetails are common spore-producing plants

Spore Formation: Spores develop in sporangia, reproductive structures on plants like ferns and mosses

Spores are the microscopic, single-celled units through which plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi reproduce asexually. Unlike seeds, which contain a young plant encased in a protective coat, spores are simple, resilient cells capable of developing into new organisms under favorable conditions. These spores form within specialized structures called sporangia, which act as factories and launchpads for this reproductive process. Understanding how sporangia function offers insight into the survival strategies of spore-producing plants, particularly in environments where traditional seed-based reproduction is less viable.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern, a prime example of a spore plant. On the underside of fern fronds, you’ll find clusters of sporangia, often grouped into structures called sori. Within each sporangium, spores develop through a process called sporogenesis. When mature, the sporangium dries out and splits open, releasing spores into the wind. This dispersal method allows ferns to colonize new areas efficiently, even in shaded or moist environments where seed germination might struggle. For gardeners cultivating ferns, ensuring adequate humidity and airflow mimics their natural habitat, encouraging healthy sporangium development and spore release.

Sporangia are not one-size-fits-all structures; their form and function vary across plant groups. In mosses, for instance, sporangia are housed in capsule-like structures atop slender stalks called setae. These capsules, often colorful and distinctive, dry out and release spores through a lid-like opening called the operculum. This mechanism ensures spores are ejected with force, increasing dispersal range. For enthusiasts growing mosses, providing a consistent moisture level and avoiding direct sunlight supports sporangium maturation, though overwatering can lead to rot, disrupting the reproductive cycle.

The efficiency of spore formation and dispersal highlights its evolutionary advantage. Spores are lightweight, durable, and capable of surviving harsh conditions, from drought to extreme temperatures. This resilience makes spore plants dominant in ecosystems where flowering plants cannot thrive, such as peat bogs or rocky outcrops. For educators or hobbyists studying plant reproduction, observing sporangia under a microscope reveals their intricate structure, offering a tangible lesson in adaptation. Pairing this with field observations of spore plants in their natural habitats reinforces the connection between form and function in biology.

Practical applications of understanding sporangia extend beyond botany. In agriculture, spore-based fungi like mycorrhizae are used to enhance soil health and nutrient uptake in crops. Knowing how sporangia develop and release spores can optimize the application of these beneficial organisms. For example, applying mycorrhizal inoculants during planting ensures spores colonize root systems effectively, improving plant vigor. Similarly, in horticulture, propagating ferns or mosses via spores requires simulating natural conditions—such as using a humid dome for spore germination—to achieve success. This knowledge bridges the gap between theoretical biology and hands-on practice, making spore formation a fascinating and useful concept to explore.

Effective Methods to Remove Mold Spores from Your Clothes Safely

You may want to see also

Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, or animals carry spores to new habitats for germination

Spores are nature’s lightweight, resilient travelers, designed to journey far and wide in search of new habitats. Their dispersal methods—wind, water, and animals—are as varied as the environments they colonize. Wind, the most common carrier, whisks spores aloft in a chaotic dance, scattering them across vast distances. Ferns, for instance, release millions of spores into the air, relying on currents to transport them to moist, shaded areas where they can germinate. This passive strategy, while unpredictable, ensures that at least some spores land in favorable conditions, maximizing the species’ survival odds.

Water, though less universal than wind, plays a critical role in spore dispersal for aquatic and semi-aquatic plants. Mosses and certain algae release spores into streams or rainwater, allowing them to drift downstream or pool in damp crevices. This method is particularly effective in dense forests or wetlands, where water flow is consistent. For example, the spores of *Salvinia*, a floating fern, are carried by surface tension, enabling them to colonize new ponds or lakes swiftly. While water dispersal is localized compared to wind, it guarantees delivery to environments already suited for growth.

Animal-mediated dispersal, though less common, is a fascinating adaptation seen in some spore-producing plants. Spores may hitch a ride on fur, feathers, or even the feet of animals, traveling to distant locations. A notable example is the club moss *Lycopodium*, whose spores are lightweight and sticky, easily adhering to passing creatures. This method is more targeted than wind or water, as animals frequent specific habitats, increasing the likelihood of spores reaching suitable environments. However, it relies on the unpredictable movements of animals, making it a high-risk, high-reward strategy.

Each dispersal method has its trade-offs. Wind offers range but lacks precision, water ensures suitability but limits distance, and animals provide specificity but depend on chance encounters. Plants often evolve multiple strategies to hedge their bets. For instance, some liverworts release spores that can be carried by both wind and water, doubling their chances of successful colonization. Understanding these mechanisms not only reveals the ingenuity of spore plants but also highlights the delicate balance between randomness and adaptation in nature’s survival toolkit.

Unveiling the Survival Secrets: How Spores Work and Thrive

You may want to see also

Germination Process: Spores activate under favorable conditions, growing into gametophytes

Spores, the microscopic units of life, lie dormant, biding their time until conditions are just right. This is the crux of the germination process, a pivotal moment in the life cycle of spore plants. When factors like moisture, temperature, and light align favorably, these resilient structures spring into action, initiating a transformation that is both intricate and essential.

Imagine a fern, its fronds unfurling in a shaded forest. This lush greenery begins its life as a spore, a tiny package of potential. Upon landing on a suitable substrate, the spore absorbs water, triggering a series of biochemical reactions. This hydration is critical, as it softens the spore wall and activates enzymes that break down stored nutrients. Within hours to days, depending on the species, the spore swells and ruptures, releasing a delicate filament called a protonema. This initial growth stage is the first visible sign of life, a harbinger of the gametophyte to come.

The protonema, often thread-like or thalloid, serves as the foundation for the gametophyte, the sexual phase of the plant. In mosses, for instance, the protonema develops buds that grow into leafy gametophores. These structures house the reproductive organs: antheridia, which produce sperm, and archegonia, which contain eggs. The process is highly dependent on environmental cues; too much light can inhibit growth, while insufficient moisture halts development altogether. For optimal results, gardeners cultivating spore plants like ferns or mosses should maintain a humidity level of 60-70% and provide indirect light, mimicking the understory conditions these plants thrive in.

Comparatively, the germination of seed plants involves embryos encased in protective coats, whereas spore plants rely on external conditions to nurture their vulnerable early stages. This makes spore germination a more delicate process, yet one that has persisted for millions of years. The adaptability of spores to harsh environments—from arid deserts to polar regions—underscores their evolutionary success. For enthusiasts, understanding this process allows for better propagation techniques, such as using a misting system to maintain moisture without oversaturating the substrate.

In conclusion, the germination of spores into gametophytes is a testament to nature’s precision and resilience. By creating conditions that mimic their natural habitats, we can witness this transformation firsthand, whether in a terrarium or a forest floor. This knowledge not only deepens our appreciation for spore plants but also empowers us to cultivate and conserve these ancient organisms effectively.

UV Light's Power: Can It Effectively Eliminate Mold Spores?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Life Cycle Types: Alternation of generations between sporophyte and gametophyte phases

Spore plants, such as ferns, mosses, and liverworts, exhibit a fascinating life cycle characterized by alternation of generations. This means their life cycle involves two distinct phases: the sporophyte and the gametophyte, each with unique structures and functions. Understanding this alternation is key to grasping how these plants reproduce and thrive in diverse environments.

Consider the fern as a prime example. The sporophyte phase, which is the fern we typically recognize, produces spores in structures called sporangia, often found on the undersides of leaves. These spores are not seeds but single-celled reproductive units. When released, a spore germinates into a gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure called a prothallus. This phase is often overlooked but is crucial: it houses the sex organs (antheridia and archegonia) that produce sperm and eggs, respectively. Fertilization occurs when sperm from one prothallus swims to an egg on another, given the right moisture conditions. The resulting zygote then grows into a new sporophyte, completing the cycle.

Analyzing this process reveals a strategic division of labor. The sporophyte phase dominates in size and longevity, focusing on spore production and dispersal. In contrast, the gametophyte phase is short-lived and dependent on moisture, specializing in sexual reproduction. This alternation ensures genetic diversity through the mixing of gametes while allowing the sporophyte to adapt to varying environmental conditions. For instance, spores are lightweight and can travel long distances, enabling colonization of new habitats.

To observe this cycle firsthand, collect fern spores by placing a mature frond on paper for a few days. Once spores are gathered, sprinkle them on a moist, shaded soil surface and keep it consistently damp. Within weeks, you’ll see tiny green prothalli emerge. For successful fertilization, ensure the environment remains humid, as sperm require water to swim to the egg. This hands-on approach not only illustrates the alternation of generations but also highlights the delicate balance required for each phase to thrive.

In practical terms, understanding this life cycle is essential for horticulture and conservation. For example, propagating ferns from spores rather than dividing mature plants ensures genetic diversity. Similarly, preserving habitats that support both sporophyte and gametophyte phases is critical for the survival of spore plants in ecosystems. By appreciating the intricacies of alternation of generations, we gain insights into the resilience and adaptability of these ancient plant forms.

Natural Ways to Eliminate Airborne Mold Spores in Your Home

You may want to see also

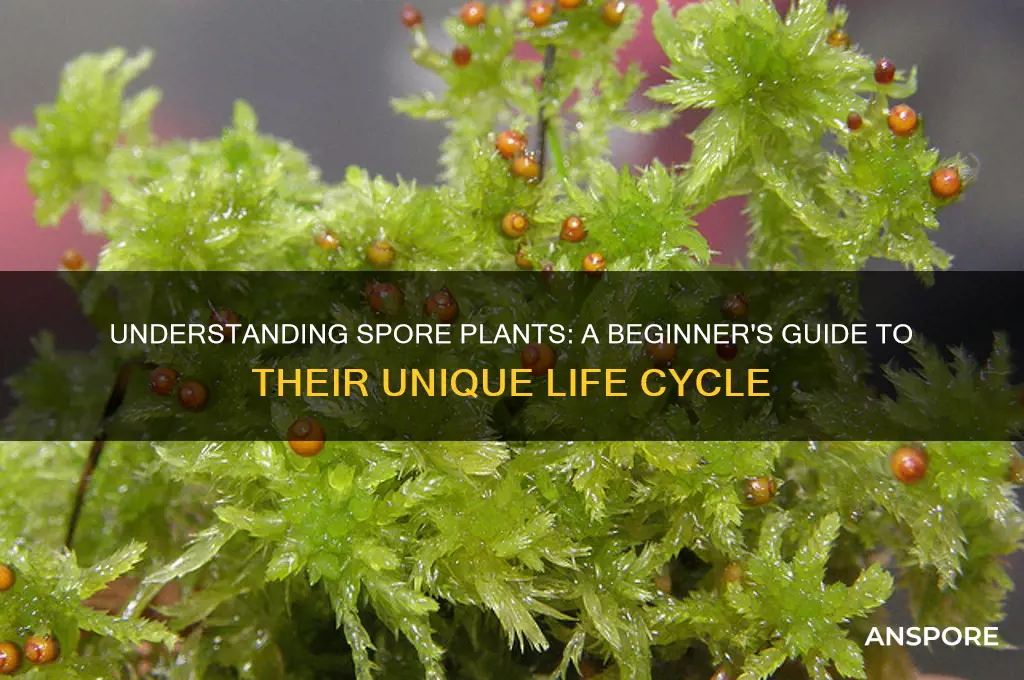

Examples of Plants: Ferns, mosses, liverworts, and horsetails are common spore-producing plants

Ferns, mosses, liverworts, and horsetails are among the most recognizable spore-producing plants, collectively known as non-seed vascular plants or bryophytes. These plants reproduce via spores rather than seeds, a method that has sustained them for millions of years. Ferns, for instance, are vascular plants with feathery fronds that unfurl in a process called "fiddlehead" growth. They thrive in moist, shaded environments and are often found in forests or along stream banks. To cultivate ferns, ensure they receive indirect light and consistent moisture, as their spore-based reproduction relies on humidity for successful dispersal and germination.

Mosses, in contrast, are non-vascular plants that form dense, carpet-like mats in damp, shady areas. They lack true roots, stems, and leaves, absorbing water and nutrients directly through their tissues. Mosses are remarkably resilient, capable of surviving desiccation and reviving when moisture returns. For gardeners, mosses can be encouraged by maintaining a consistently damp environment and avoiding direct sunlight. Their spores are microscopic and disperse easily, making them a low-maintenance addition to shaded landscapes or terrariums.

Liverworts, often mistaken for mosses, are distinguished by their flattened, lobed bodies resembling liver (hence the name). They are among the simplest land plants and thrive in moist, humid conditions. Unlike mosses, some liverworts exhibit a thalloid structure, while others grow in branching patterns. To grow liverworts, mimic their natural habitat by using a substrate rich in organic matter and keeping it perpetually moist. Their spores are produced in structures called gemmae cups, which can be used for propagation, offering a hands-on way to study their unique reproductive cycle.

Horsetails, the only living genus of the class Equisetopsida, are vascular plants with jointed, hollow stems resembling bamboo. They are relics of the Carboniferous period, once towering as tree-sized plants. Modern horsetails are smaller but equally fascinating, often found in wetlands or along water bodies. Their spores are produced in cone-like structures at the tips of fertile stems. While horsetails can be invasive, they serve as a living link to Earth’s ancient flora. To manage them, avoid overwatering and consider planting them in contained areas to prevent spread.

Each of these spore-producing plants plays a unique ecological role, from mosses stabilizing soil to ferns providing habitat for small organisms. Their reliance on spores for reproduction highlights an ancient, efficient strategy that predates seeds. For enthusiasts, cultivating these plants offers a window into the diversity of plant life and the resilience of spore-based systems. Whether in a garden, terrarium, or natural setting, ferns, mosses, liverworts, and horsetails remind us of the enduring adaptability of Earth’s earliest flora.

Spore Game Pricing: Cost Details and Purchase Options Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A spore plant, also known as a non-seed plant, is a type of plant that reproduces through spores rather than seeds. Examples include ferns, mosses, and fungi.

Spore plants reproduce by releasing tiny, single-celled spores that develop into new plants under favorable conditions. This process is called alternation of generations.

Common examples of spore plants include ferns, mosses, liverworts, horsetails, and clubmosses. Fungi, though not true plants, also reproduce via spores.

No, spore plants do not produce flowers or seeds. They rely solely on spores for reproduction, which are often dispersed by wind or water.