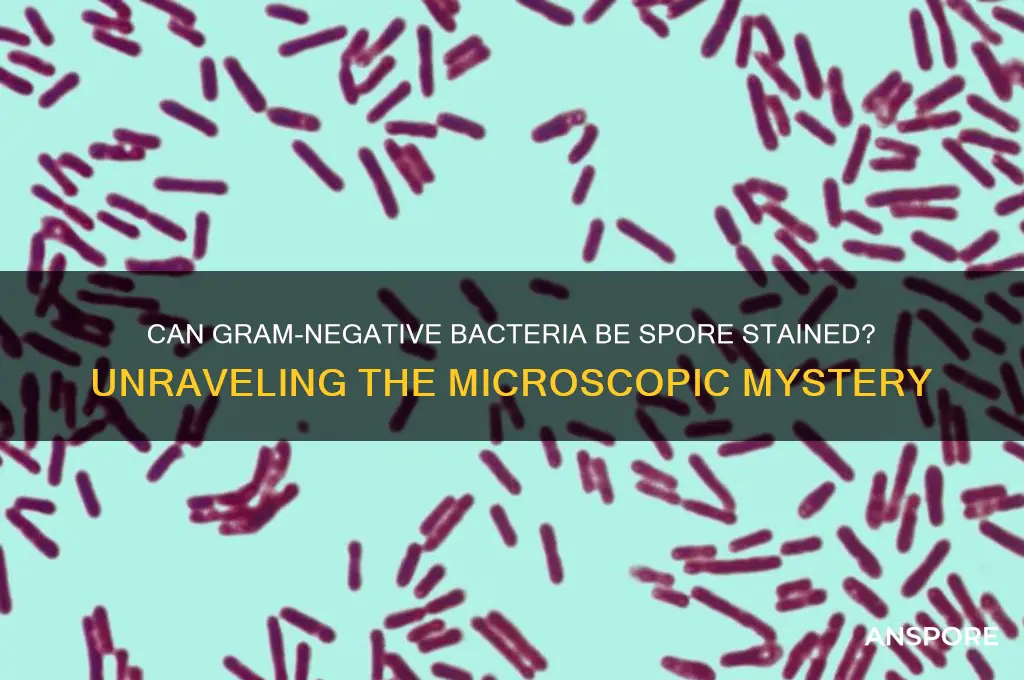

Gram-negative bacteria are a diverse group of microorganisms characterized by their thin peptidoglycan cell wall and outer membrane containing lipopolysaccharides, which distinguish them from gram-positive bacteria. While spore formation is a well-known survival mechanism in certain gram-positive bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species, it is generally uncommon among gram-negative bacteria. However, the question of whether gram-negative bacteria can be spore-stained arises due to rare exceptions like *Adenylosuccinate synthetase* (AdSS) in *Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus*, which exhibits spore-like structures under specific conditions. Traditional spore staining techniques, such as the Schaeffer-Fulton or Dorner methods, are designed to differentiate spores from vegetative cells based on their resistance to heat and dyes. While these methods are not typically applied to gram-negative bacteria, understanding the potential for spore-like structures in certain species highlights the complexity and adaptability of bacterial survival strategies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can Gram-negative bacteria form spores? | No, most Gram-negative bacteria cannot form spores. Sporulation is a characteristic primarily associated with certain Gram-positive bacteria, particularly those in the genus Bacillus and Clostridium. |

| Exceptions | A few rare exceptions exist, such as Xanthomonas spp. and Azotobacter spp., which are Gram-negative bacteria capable of producing cyst-like structures, but these are not true spores. |

| Spore staining applicability | Since Gram-negative bacteria generally do not form spores, spore staining techniques (e.g., Schaeffer-Fulton stain) are not applicable to them. These techniques are specifically designed to detect endospores in Gram-positive bacteria. |

| Relevance of spore staining | Spore staining is used to differentiate between vegetative cells and endospores in Gram-positive bacteria, aiding in identification and diagnosis. It has no relevance for Gram-negative bacteria due to their inability to form spores. |

| Alternative staining methods | For Gram-negative bacteria, standard Gram staining is used for identification and differentiation based on cell wall structure. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Stain Principles: Understanding the basic principles and mechanisms of spore staining techniques in microbiology

- Gram-Negative Characteristics: Key traits of Gram-negative bacteria that may affect spore staining outcomes

- Spore Formation in Gram-Negatives: Investigating if and how Gram-negative bacteria can form spores

- Staining Protocol Adjustments: Modifications needed in spore staining for Gram-negative bacterial samples

- Interpretation of Results: Analyzing and interpreting spore stain results for Gram-negative bacteria accurately

Spore Stain Principles: Understanding the basic principles and mechanisms of spore staining techniques in microbiology

Spore staining is a specialized technique in microbiology designed to differentiate bacterial spores from vegetative cells. Unlike standard Gram staining, which categorizes bacteria based on cell wall composition, spore staining targets the unique structural and chemical properties of spores. The primary principle involves the use of heat and specific dyes to penetrate the highly resistant spore coat, which is composed of keratin-like proteins and is impermeable to most stains. The most commonly employed method is the Schaeffer-Fulton stain, which utilizes malachite green as the primary dye and heat to force the dye into the spore. This process is followed by a counterstain, typically safranin, to color the vegetative cells, allowing for clear differentiation under a microscope.

The mechanism of spore staining hinges on the spore’s resilience to heat and chemicals. During the staining process, the heat application not only drives the malachite green into the spore but also fixes the dye, ensuring it remains bound even after subsequent washing steps. This is critical because spores are notoriously difficult to stain due to their impermeable outer layers. The counterstain, safranin, colors the vegetative cells pink or red, while the spores retain the green color of malachite green. This dual-color system enables microbiologists to identify spore-forming bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species, with precision. It’s important to note that spore staining is not applicable to Gram-negative bacteria, as they do not form spores. Spore formation is a characteristic primarily of certain Gram-positive bacteria, particularly those in the Firmicutes phylum.

To perform a successful spore stain, follow these steps: First, prepare a heat-fixed smear of the bacterial sample on a microscope slide. Next, cover the smear with malachite green and apply heat using a steam source or a Bunsen burner for 5–10 minutes. This step is crucial for forcing the dye into the spores. After cooling, wash the slide with water to remove excess dye, then decolorize using water for 30–60 seconds. Counterstain with safranin for 2–5 minutes, wash again, and allow the slide to air dry. Examine under oil immersion (1000X magnification) to observe green spores against a pink background of vegetative cells. Caution must be exercised when applying heat to avoid overheating, which can damage the slide or sample.

The analytical value of spore staining lies in its ability to identify spore-forming bacteria, which are often associated with food spoilage, medical infections, and environmental resilience. For instance, *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax, can be readily identified through spore staining due to its distinctive green spores. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria like *Escherichia coli* or *Pseudomonas aeruginosa* will not produce spores and thus cannot be spore stained. This distinction is vital in diagnostic microbiology, as it helps narrow down potential pathogens and guides appropriate treatment strategies. Understanding the principles of spore staining ensures accurate identification and differentiation of bacterial species in clinical and research settings.

In conclusion, spore staining is a specialized technique rooted in the unique properties of bacterial spores. By leveraging heat and specific dyes, microbiologists can distinguish spores from vegetative cells, a capability essential for identifying spore-forming bacteria. While Gram-negative bacteria are excluded from this process due to their inability to form spores, the technique remains indispensable for studying and diagnosing spore-forming Gram-positive organisms. Mastery of spore staining principles and protocols enhances the precision and reliability of microbiological analyses, contributing to advancements in medicine, food safety, and environmental science.

Are Moss Spores Identical? Unveiling the Diversity in Moss Reproduction

You may want to see also

Gram-Negative Characteristics: Key traits of Gram-negative bacteria that may affect spore staining outcomes

Gram-negative bacteria possess a unique cell wall structure that significantly impacts their interaction with staining techniques, including spore staining. Unlike Gram-positive bacteria, which have a thick peptidoglycan layer, Gram-negative bacteria feature a thin peptidoglycan layer sandwiched between an inner and outer membrane. This complex architecture affects the permeability and retention of stains, making spore staining outcomes less predictable. The outer membrane, in particular, contains lipopolysaccharides that can repel certain dyes, complicating the process of visualizing spores in these organisms.

One key trait of Gram-negative bacteria that affects spore staining is their outer membrane’s low permeability. During the staining process, the initial application of a primary stain (e.g., malachite green) requires penetration of this barrier to reach the spore. However, the lipophilic nature of the outer membrane often restricts dye entry, leading to incomplete or inconsistent staining. Prolonging the staining time or increasing the temperature (e.g., steaming for 5–10 minutes) can enhance dye penetration, but this must be balanced to avoid damaging the sample.

Another critical factor is the presence of endospore location within Gram-negative bacteria. While endospores are more commonly associated with Gram-positive genera like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, some Gram-negative bacteria, such as *Chromobacterium violaceum*, can produce spore-like structures. These structures may differ in composition and staining affinity compared to typical endospores. For instance, the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria may shield these structures, requiring additional steps like gentle detergent treatment to improve stain accessibility.

Practical tips for spore staining in Gram-negative bacteria include using a safranin counterstain to highlight background structures, as the primary stain may not fully penetrate the outer membrane. Additionally, employing a decolorizer (e.g., water or alcohol) cautiously is essential, as over-decolorization can wash away weakly bound stains. For research or diagnostic purposes, combining spore staining with other techniques, such as electron microscopy or molecular methods, can provide more reliable results when working with Gram-negative organisms.

In conclusion, the Gram-negative cell wall’s complexity, particularly its outer membrane, poses unique challenges for spore staining. Understanding these structural traits allows for tailored adjustments to staining protocols, improving the likelihood of accurate and interpretable results. While Gram-negative bacteria are less commonly associated with spore formation, recognizing their staining limitations is crucial for both laboratory efficiency and scientific accuracy.

How Spores Spread: Person-to-Person Transmission Explained

You may want to see also

Spore Formation in Gram-Negatives: Investigating if and how Gram-negative bacteria can form spores

Gram-negative bacteria are traditionally classified as non-spore formers, a trait that distinguishes them from their Gram-positive counterparts like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*. However, recent research challenges this dogma, revealing that certain Gram-negative species can indeed produce spore-like structures under specific conditions. For instance, *Chromobacterium violaceum* and *Xanthomonas* spp. have been observed to form resilient, dormant cells resembling spores in response to environmental stressors such as nutrient deprivation or desiccation. These findings prompt a reevaluation of the mechanisms and conditions under which Gram-negative bacteria might adopt sporulation-like strategies for survival.

To investigate spore formation in Gram-negatives, researchers employ a combination of molecular biology, microscopy, and staining techniques. The traditional spore staining method, which involves heat fixation and differential staining with malachite green and safranin, is often adapted to detect these spore-like structures. However, due to the thinner peptidoglycan layer and outer membrane of Gram-negatives, modifications such as prolonged heating or the use of detergents may be necessary to enhance permeability. For example, a study on *Chromobacterium violaceum* utilized a modified spore staining protocol with 10% sodium hypochlorite pretreatment to remove the outer membrane, followed by standard spore staining, successfully highlighting the spore-like structures under bright-field microscopy.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore formation in Gram-negatives has significant implications for industries such as food safety, healthcare, and environmental management. If Gram-negative bacteria can form spores, their ability to survive harsh conditions like pasteurization or disinfection protocols could pose new challenges. For instance, *Xanthomonas campestris*, a plant pathogen, has been shown to produce spore-like cells that resist standard sterilization methods, potentially leading to persistent infections in agricultural settings. This underscores the need for updated detection and eradication strategies tailored to these resilient forms.

Comparatively, while Gram-positive spore formers like *Bacillus anthracis* have well-characterized sporulation pathways regulated by genes such as *spo0A*, the genetic basis of spore-like formation in Gram-negatives remains poorly understood. Preliminary studies suggest that stress response pathways, particularly those involving sigma factors and heat shock proteins, may play a role. For example, overexpression of the *rpoS* gene in *Escherichia coli* has been linked to increased stress tolerance and the formation of dormant, spore-like cells. Further genomic and transcriptomic analyses are needed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms driving this phenomenon in Gram-negatives.

In conclusion, while Gram-negative bacteria are not traditionally considered spore formers, emerging evidence suggests that certain species can produce spore-like structures under stress. Investigating this phenomenon requires tailored staining techniques and a deeper understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms. The implications of such findings are far-reaching, impacting fields from microbiology to public health, and highlight the need for continued research to fully grasp the survival strategies of these versatile organisms.

Understanding the Meaning and Usage of 'Spor' in Language and Culture

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Staining Protocol Adjustments: Modifications needed in spore staining for Gram-negative bacterial samples

Gram-negative bacteria present unique challenges in spore staining due to their distinct cell wall composition, which lacks the thick peptidoglycan layer found in Gram-positive bacteria. This structural difference necessitates specific adjustments to the standard spore staining protocol to ensure accurate and reliable results. The primary goal is to enhance spore visibility without compromising the integrity of the Gram-negative cell wall.

One critical modification involves the heat fixation step. Gram-negative bacteria are more susceptible to heat damage, which can lead to cell lysis and loss of spores. To mitigate this, reduce the heat fixation time to 2–3 minutes instead of the standard 5 minutes. Alternatively, use a chemical fixation method with 10% formalin for 10 minutes at room temperature. This gentler approach preserves cell integrity while adequately preparing the sample for staining.

Another adjustment lies in the application of the primary stain. Malachite green, the traditional spore stain, requires prolonged heating to penetrate spores effectively. However, this can further stress Gram-negative cells. To address this, reduce the steaming time to 3–5 minutes and monitor the sample closely to avoid overheating. Additionally, increasing the concentration of malachite green to 0.5% can enhance staining efficiency without extending the heating duration.

Decolorization is a delicate step that requires careful attention. Gram-negative bacteria are more prone to decolorization-induced damage due to their thinner cell walls. Use a milder decolorizing agent, such as a 1:1 mixture of 95% ethanol and water, instead of pure ethanol. Apply the decolorizer for 30–60 seconds, ensuring thorough rinsing with water afterward to prevent over-decolorization.

Finally, the counterstain step must be optimized to differentiate vegetative cells from spores effectively. Safranin, the standard counterstain, can be used at a concentration of 0.5% for 2–3 minutes. However, for Gram-negative samples, consider using basic fuchsin (0.3%) as an alternative counterstain, as it provides better contrast and reduces background staining. Ensure the sample is thoroughly rinsed and blot-dried before examination under a microscope.

In summary, staining Gram-negative bacteria for spores requires tailored adjustments to the standard protocol. By reducing heat fixation time, optimizing staining and decolorization steps, and selecting appropriate counterstains, microbiologists can achieve clear and accurate results while preserving the integrity of these delicate organisms. These modifications ensure that spore staining remains a reliable technique for identifying spore-forming Gram-negative bacteria in clinical and research settings.

Are Spores a Form of Sexual Reproduction in Plants?

You may want to see also

Interpretation of Results: Analyzing and interpreting spore stain results for Gram-negative bacteria accurately

Gram-negative bacteria are not typically known for forming spores, a trait more commonly associated with certain Gram-positive species like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*. However, interpreting spore stain results for Gram-negative bacteria requires a nuanced understanding of both the staining technique and the biological characteristics of these organisms. The spore stain, or endospore stain, is designed to differentiate between vegetative cells and endospores, which are highly resistant structures. When applying this technique to Gram-negative bacteria, the primary challenge lies in distinguishing between false positives and genuine spore-like structures, as some Gram-negative species may exhibit spore-like inclusions under certain conditions.

To accurately interpret spore stain results, begin by examining the morphology and staining characteristics of the cells. Endospores typically appear as small, refractile bodies within or alongside the vegetative cells, staining green with malachite green and remaining unstained by the counterstain safranin. In Gram-negative bacteria, however, structures like polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) granules or other storage inclusions may mimic spores in size and shape but will not exhibit the same resistance to heat or staining. For example, *Escherichia coli* or *Pseudomonas* species may show granular inclusions, but these will not retain malachite green after the staining process.

A critical step in interpretation is correlating the stain results with the known biology of the organism. While true endospores are rare in Gram-negative bacteria, some species, such as *Adenosynbacter* or *Oceanibacillus*, have been reported to produce spore-like structures under specific environmental stresses. If spore-like structures are observed, consider the growth conditions and media used, as nutrient deprivation or extreme conditions can induce stress responses that mimic sporulation. For instance, high-pressure environments or prolonged starvation may trigger the formation of spore-like inclusions in certain Gram-negative species.

Practical tips for accurate interpretation include using a high-quality microscope with proper magnification (1000x or higher) to clearly visualize the structures and performing control stains with known spore-forming and non-spore-forming organisms. Additionally, heat fixation prior to staining can help differentiate true endospores from other inclusions, as endospores are highly heat-resistant. If uncertainty persists, molecular techniques like PCR targeting sporulation genes (e.g., *spo0A*) can provide confirmatory evidence.

In conclusion, interpreting spore stain results for Gram-negative bacteria demands a combination of careful observation, biological knowledge, and critical thinking. While true endospores are uncommon in this group, understanding the limitations of the staining technique and the potential for spore-like structures under stress conditions is essential for accurate analysis. By integrating morphological, environmental, and molecular data, microbiologists can confidently distinguish between genuine spores and artifacts, ensuring reliable results in both research and clinical settings.

Are Mirasmius Spores White? Unveiling the Truth About Their Color

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Some Gram-negative bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, can form spores, but they are typically Gram-positive. Most Gram-negative bacteria do not form spores.

Spore staining techniques, like the Schaeffer-Fulton method, are primarily used for detecting endospores in Gram-positive bacteria. Gram-negative bacteria do not produce endospores, so spore staining is not applicable to them.

Spore staining is used to identify and differentiate bacterial endospores, which are primarily found in Gram-positive bacteria. It is not relevant for Gram-negative bacteria, as they do not produce spores.