Grass reproduction is a fascinating subject, primarily occurring through seeds or vegetative means like rhizomes and stolons. However, the question of whether grass can reproduce from spores is intriguing, as spores are typically associated with non-vascular plants like ferns and fungi. Grasses, being flowering plants (angiosperms), do not produce spores for reproduction. Instead, they rely on pollination and seed dispersal for their life cycle. While some plants, like ferns, use spores for asexual reproduction, grasses have evolved distinct mechanisms to ensure their survival and propagation in diverse environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Method | Grass primarily reproduces through seeds (sexual reproduction) or vegetatively (asexual reproduction via rhizomes, stolons, or tillers). |

| Spores in Grass | Grass does not produce spores. Spores are typically associated with non-vascular plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi, not grasses. |

| Seed Production | Grasses produce seeds enclosed in structures like spikelets or florets, which are dispersed by wind, animals, or water. |

| Vegetative Reproduction | Grass can spread via rhizomes (underground stems), stolons (above-ground runners), or tillers (side shoots), allowing clonal growth. |

| Role of Spores | Spores are not involved in grass reproduction. Grasses lack the sporophyte-gametophyte alternation of generations seen in spore-producing plants. |

| Scientific Classification | Grasses belong to the family Poaceae, which reproduces through seeds and vegetative means, not spores. |

| Misconception | The idea that grass reproduces from spores is incorrect; it is a common misunderstanding due to confusion with spore-producing plants. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Grass Reproduction Methods: Grasses primarily reproduce through seeds, not spores, unlike ferns or fungi

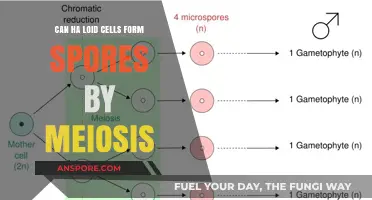

- Spores vs. Seeds: Spores are haploid; seeds contain embryos, distinct reproductive strategies

- Grass Life Cycle: Grasses follow a seed-based life cycle, no spore stage involved

- Asexual Reproduction: Grasses can reproduce asexually via rhizomes or stolons, not spores

- Misconceptions About Spores: Grasses lack spore-producing structures; spores are unrelated to grass reproduction

Grass Reproduction Methods: Grasses primarily reproduce through seeds, not spores, unlike ferns or fungi

Grasses, unlike ferns or fungi, do not rely on spores for reproduction. Instead, their primary method of propagation is through seeds, a characteristic that sets them apart in the plant kingdom. This seed-based reproduction is a key factor in their success as one of the most widespread plant families on Earth. Grasses produce flowers that, after pollination, develop into seeds containing all the necessary genetic material for a new plant. These seeds are often dispersed by wind, water, or animals, allowing grasses to colonize diverse environments, from lush meadows to arid savannas.

To understand the efficiency of seed reproduction in grasses, consider the structure of a grass seed. It consists of an embryo, endosperm (nutrient storage), and a protective seed coat. This design ensures the seed can survive harsh conditions, such as drought or cold, until optimal germination conditions arise. For example, lawn grasses like Kentucky bluegrass produce seeds that can remain dormant in soil for years, sprouting only when moisture and temperature are ideal. This adaptability contrasts sharply with spore-based reproduction, which typically requires specific environmental conditions to thrive.

While spores are lightweight and numerous, allowing ferns and fungi to disperse widely, grass seeds offer a different advantage: energy reserves. The endosperm provides the emerging seedling with nutrients during its early growth stages, increasing its chances of survival. This is particularly crucial in competitive ecosystems where resources are limited. For instance, in agricultural settings, farmers often select grass varieties with robust seed production to ensure dense, healthy pastures or lawns. Techniques like overseeding—spreading grass seed over an existing lawn—exploit this natural reproductive strategy to fill bare patches and improve turf density.

Comparatively, spore reproduction in ferns and fungi relies on external factors like humidity and shade, limiting their habitats. Grasses, however, have evolved to thrive in open, sunny environments by investing in seed production. This is evident in species like wheat and rice, where seeds are not only reproductive units but also staple food sources for humans. The domestication of these grasses highlights how their seed-based reproduction has been harnessed for global agriculture, a feat spore-reproducing plants have not achieved to the same extent.

In practical terms, understanding grass reproduction through seeds is essential for gardening, farming, and land management. For homeowners, knowing that grass spreads via seeds explains why regular mowing (which prevents seed formation) helps control its growth. For farmers, selecting seed varieties with traits like drought resistance or high yield directly leverages this reproductive method. While spores play no role in grass reproduction, seeds are the cornerstone of their dominance in ecosystems and human cultivation, making them a fascinating subject for both naturalists and practitioners alike.

Breloom's Spore Move: Learning Level and Battle Strategy Guide

You may want to see also

Spores vs. Seeds: Spores are haploid; seeds contain embryos, distinct reproductive strategies

Grass, a ubiquitous plant in lawns, fields, and ecosystems, primarily reproduces through seeds, not spores. This distinction is rooted in the fundamental differences between spores and seeds as reproductive structures. Spores, characteristic of ferns, mosses, and fungi, are haploid cells produced by parent plants through asexual means. In contrast, seeds, the hallmark of flowering plants like grass, are the product of sexual reproduction, containing a diploid embryo that develops into a new plant.

To understand why grass relies on seeds, consider the reproductive strategies of spore-producing plants versus seed-producing plants. Spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind or water, allowing them to colonize new areas rapidly. However, their haploid nature means they are more susceptible to environmental stresses and genetic limitations. Seeds, on the other hand, are protected by a coat and often contain stored nutrients, providing the embryo with a head start in germination. For grass, this strategy ensures survival in diverse environments, from arid soils to lush meadows.

A practical example highlights this difference: when you plant grass seed, you’re introducing a self-contained unit with everything needed to grow—embryo, nutrients, and protective layers. Spores, lacking these resources, require specific conditions like moisture and shade to develop into gametophytes before reproduction can occur. For homeowners or gardeners, this means grass seed is a reliable, efficient choice for establishing or repairing lawns, whereas spore-based reproduction would be unpredictable and resource-intensive.

From an evolutionary perspective, the seed’s complexity offers grass a competitive edge. While spores dominate in stable, undisturbed habitats like forests, seeds thrive in dynamic environments where adaptability is key. Grass’s ability to produce seeds with varying genetic traits allows it to evolve resistance to pests, diseases, and climate changes. For instance, modern turfgrass varieties are bred for drought tolerance, a trait passed down through seeds, not spores.

In conclusion, while spores and seeds both serve reproductive purposes, their structures and strategies differ dramatically. Grass’s reliance on seeds underscores its success as a resilient, widespread plant. For anyone working with grass—whether planting a lawn or studying ecosystems—understanding this distinction provides valuable insights into its growth, maintenance, and ecological role. Seeds, not spores, are the cornerstone of grass reproduction, offering a robust mechanism for survival and propagation.

Does Alcohol Spray Effectively Kill Bacterial Spores? A Comprehensive Analysis

You may want to see also

Grass Life Cycle: Grasses follow a seed-based life cycle, no spore stage involved

Grasses, those ubiquitous plants that blanket lawns, fields, and prairies, rely on a seed-based life cycle for reproduction. Unlike ferns or fungi, which disperse spores to propagate, grasses produce seeds as their primary means of continuation. This fundamental difference shapes their growth patterns, ecological roles, and even their resilience in diverse environments. Understanding this seed-centric cycle is key to appreciating how grasses dominate vast landscapes and support ecosystems worldwide.

The life cycle of grass begins with seed germination, a process triggered by moisture, warmth, and adequate soil conditions. Once a seed sprouts, it develops into a seedling, characterized by slender leaves and a delicate root system. During this stage, the plant focuses on establishing itself, drawing nutrients from the soil and sunlight through photosynthesis. For optimal growth, ensure seeds are sown at a depth of ¼ to ½ inch, depending on the species, and maintain consistent moisture to prevent drying.

As the grass matures, it enters the vegetative stage, where it expands through tillering—the production of lateral shoots. This phase is critical for lawn density and pasture coverage. Grasses like Kentucky bluegrass or perennial ryegrass thrive during this period, forming dense mats that crowd out weeds. To encourage robust growth, apply a balanced fertilizer with a nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium (N-P-K) ratio of 10-10-10, following package instructions for application rates based on grass type and soil conditions.

The final stage is reproductive, where grasses produce flowers and seeds. These structures are often inconspicuous, such as the feathery seed heads of timothy grass or the spikelets of Bermuda grass. While this stage ensures genetic continuity, it can be less desirable for lawns, as energy diverted to seed production may reduce overall turf vigor. Mowing regularly, ideally removing no more than one-third of the blade height at a time, can delay flowering and maintain a lush appearance.

In summary, grasses’ seed-based life cycle—germination, vegetative growth, and reproduction—is a testament to their adaptability and efficiency. By focusing on seeds rather than spores, they’ve evolved to colonize diverse habitats, from arid deserts to lush wetlands. For gardeners, farmers, or ecologists, mastering this cycle enables better management, whether cultivating a pristine lawn or restoring a grassland ecosystem. No spores are involved, just the quiet, persistent power of seeds.

Are Mirasmius Spores White? Unveiling the Truth About Their Color

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$23.99 $29.99

Asexual Reproduction: Grasses can reproduce asexually via rhizomes or stolons, not spores

Grasses are among the most successful plants on Earth, covering vast landscapes and playing a critical role in ecosystems and agriculture. While many plants rely on spores for reproduction, grasses take a different path. They reproduce asexually through specialized structures called rhizomes and stolons, not spores. This method allows them to spread efficiently, colonize new areas, and maintain genetic consistency, ensuring their dominance in diverse environments.

Rhizomes and stolons are horizontal stems that grow underground or along the soil surface, respectively. Rhizomes, like those found in Kentucky bluegrass, develop roots and shoots at nodes, enabling the grass to form dense mats or patches. Stolons, characteristic of Bermuda grass, grow above ground and root at nodes, creating a network of interconnected plants. Both structures allow grasses to expand their territory without relying on seeds or spores, making them highly effective at vegetative propagation. For gardeners or landscapers, understanding this mechanism is key to managing grass growth, whether controlling invasive species or encouraging lawn density.

Asexual reproduction via rhizomes and stolons offers distinct advantages. It ensures that the new plants are genetically identical to the parent, preserving desirable traits such as drought resistance or color. This consistency is particularly valuable in turfgrass cultivation, where uniformity is prized. However, it also limits genetic diversity, which can make grass populations more vulnerable to pests or diseases. For instance, a single fungus or insect that targets a specific grass variety could spread rapidly through a monoculture. Balancing the benefits of asexual reproduction with the need for genetic variation is a practical consideration for anyone managing large grass areas.

To harness the power of rhizomes and stolons, consider these practical tips. When planting grass, choose varieties with strong rhizomatous or stoloniferous growth if rapid coverage is desired. For example, Bermuda grass is ideal for warm climates due to its aggressive stolon growth, while creeping bentgrass thrives in cooler regions with its rhizome-driven spread. Regularly divide and replant sections of grass to encourage healthy expansion, but monitor for overgrowth, especially in mixed plant beds where grasses can outcompete other species. For lawns, aeration and dethatching can enhance rhizome and stolon development by reducing soil compaction and promoting nutrient absorption.

In conclusion, while spores are absent from grass reproduction, rhizomes and stolons provide a robust alternative. These structures enable grasses to thrive through asexual means, offering both reliability and challenges. By understanding and managing this process, individuals can optimize grass growth for specific needs, whether for aesthetic lawns, agricultural fields, or ecological restoration. The key lies in recognizing the unique capabilities of these underground and surface stems, turning them into tools for successful plant management.

Tracking Black Non-Toxic Spores: Can They Enter Your Home?

You may want to see also

Misconceptions About Spores: Grasses lack spore-producing structures; spores are unrelated to grass reproduction

Grasses, with their ubiquitous presence in lawns, fields, and ecosystems, are primarily known for their seed-based reproduction. However, a common misconception persists: the idea that grasses can reproduce from spores. This confusion likely stems from the association of spores with plant reproduction, particularly in ferns and fungi. Grasses, however, lack spore-producing structures entirely, relying instead on flowers and seeds for propagation. Understanding this distinction is crucial for gardeners, botanists, and anyone interested in plant biology, as it clarifies the mechanisms driving grass growth and dispel myths about their reproductive strategies.

To address this misconception, it’s essential to examine the reproductive anatomy of grasses. Grasses belong to the family Poaceae and produce flowers that develop into seeds, not spores. These flowers, often inconspicuous, are arranged in structures called spikelets, which form the familiar seed heads. Pollination occurs via wind, and the resulting seeds are dispersed by wind, animals, or human activity. In contrast, spore-producing plants, such as ferns and mosses, rely on structures like sporangia to release spores, which develop into gametophytes for sexual reproduction. Grasses lack these structures, making spore-based reproduction biologically impossible for them.

A practical example illustrates this point: consider a lawn overseeding project. Gardeners spread grass seed to thicken turf, relying on germination and seedling growth. If spores were involved, one might expect to scatter spore-like particles instead. However, this approach would yield no results, as grasses cannot develop from spores. This highlights the importance of using seeds, not spores, for grass cultivation. For optimal results, select high-quality seed varieties suited to your climate and soil type, and follow recommended sowing rates—typically 5 to 10 grams of seed per square meter for overseeding.

Persuasively, it’s worth emphasizing that conflating spores with grass reproduction can lead to ineffective gardening practices. For instance, mistaking spore-based methods for grass propagation may cause individuals to overlook proper seeding techniques, such as soil preparation, watering, and timing. Grass seeds require direct contact with soil and consistent moisture to germinate, whereas spores often need specific environmental conditions to develop. By focusing on seed-based strategies, gardeners can achieve healthier, more robust lawns and meadows, avoiding the pitfalls of misinformation.

In conclusion, grasses do not reproduce from spores due to their lack of spore-producing structures and their reliance on seeds for propagation. This distinction is fundamental for anyone working with grasses, whether in agriculture, landscaping, or ecology. By understanding the biology behind grass reproduction, individuals can make informed decisions, ensuring successful growth and dispelling misconceptions about spores in the process. Always prioritize seed-based methods for grass cultivation, and remember: when it comes to grasses, seeds are the key to thriving vegetation.

Natural Ways to Eliminate Airborne Mold Spores in Your Home

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, grass does not reproduce from spores. Grasses are flowering plants (angiosperms) that reproduce primarily through seeds or vegetatively via rhizomes, stolons, or tillers.

No, grasses do not produce spores. Spores are typically associated with non-vascular plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi, not with grasses or other flowering plants.

Grass reproduces through seeds, which are produced after pollination of its flowers. It can also reproduce vegetatively through underground stems (rhizomes) or above-ground runners (stolons), allowing it to spread and form dense stands.