Haloarchaea, commonly known as halophilic archaea, are extremophiles thriving in high-salt environments. Unlike bacteria and eukaryotes, these microorganisms possess unique cellular structures and metabolic pathways. A common question arises regarding their reproductive capabilities: can haloarchaea form spores through meiosis? Meiosis, a process involving genetic recombination and cell division, is typically associated with eukaryotic organisms for sexual reproduction and spore formation. However, haloarchaea, being archaea, lack a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles, and their reproductive mechanisms differ significantly. While some archaea can form endospores or cysts under stressful conditions, these structures are not formed through meiosis. Instead, haloarchaea primarily reproduce asexually through binary fission, and their ability to form spores, if any, does not involve meiotic processes. Thus, the concept of haloarchaea forming spores by meiosis is biologically inaccurate, highlighting the distinct reproductive strategies of these extremophiles.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process Involved | Meiosis |

| Cell Type | Haploid |

| Ability to Form Spores | Yes, haploid cells can form spores through meiosis |

| Type of Spores Formed | Haploid spores (typically ascospores or basidiospores in fungi) |

| Organisms Involved | Fungi (e.g., Ascomycetes, Basidiomycetes), some algae, and certain plants |

| Purpose of Spore Formation | Asexual reproduction, dispersal, and survival in adverse conditions |

| Genetic Outcome | Haploid spores retain the genetic material from the parent cell after meiosis |

| Life Cycle Stage | Part of the sexual reproduction cycle in fungi and some other organisms |

| Comparison to Vegetative Cells | Unlike vegetative cells, spores are dormant and highly resistant to environmental stresses |

| Examples of Spore-Forming Organisms | Yeasts, molds, mushrooms, and fern gametophytes |

| Meiosis Requirement | Essential for genetic diversity and reduction of chromosome number in spores |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Meiosis in Haloid Cells: Understanding if haloid cells undergo meiosis for spore formation

- Spore Formation Mechanisms: Exploring how spores are formed in haloid cells, if applicable

- Haloid Cell Life Cycle: Analyzing the role of meiosis in haloid cell reproduction

- Comparative Sporulation Processes: Comparing haloid cell sporulation with other organisms' methods

- Genetic Basis of Sporulation: Investigating genes involved in haloid cell spore development via meiosis

Meiosis in Haloid Cells: Understanding if haloid cells undergo meiosis for spore formation

Haloid cells, a term often associated with certain types of algae, particularly in the context of their life cycles, present an intriguing question regarding their reproductive mechanisms. The process of spore formation is a critical aspect of their survival and propagation, but the role of meiosis in this process is not universally applicable across all organisms. In the case of haloid cells, understanding whether they undergo meiosis for spore formation requires a deep dive into their biological characteristics and life cycle stages.

Analyzing the Life Cycle of Haloid Cells

Haloid cells, commonly found in algae like *Chara* (a genus of green algae), exhibit a complex life cycle involving alternation of generations. This cycle typically includes both haploid and diploid phases. Spores are often produced during the haploid phase, but the mechanism of their formation varies. In some algae, spores are formed through mitosis, while in others, meiosis plays a pivotal role. For haloid cells, the key lies in identifying whether their spores are the result of meiotic division, which would reduce the chromosome number, or if they are produced asexually through mitosis. Research indicates that in *Chara*, for instance, meiosis is indeed involved in the formation of certain types of spores, such as zygospores, which are produced after the fusion of gametes.

Comparative Insights from Algal Reproduction

To understand meiosis in haloid cells, it’s helpful to compare them with other algal groups. In red algae (Rhodophyta), spores are often formed through mitosis, maintaining the diploid state. In contrast, green algae (Chlorophyta), which include haloid cells, frequently employ meiosis for spore formation. This comparison highlights the diversity in reproductive strategies among algae. For haloid cells, the involvement of meiosis is more aligned with the green algal lineage, where haploid spores are typically produced through meiotic division. This ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, crucial for survival in varying environments.

Practical Implications and Observations

For researchers and educators studying haloid cells, observing spore formation under a microscope can provide direct evidence of meiotic activity. Look for the characteristic stages of meiosis, such as the pairing of homologous chromosomes during prophase I and the reduction in chromosome number by half. Practical tips include using stains like aceto-carmine to highlight cell nuclei and tracking cell divisions over time. For instance, in a laboratory setting, culturing *Chara* in controlled conditions (e.g., 20-25°C, 12-hour light/dark cycles) can facilitate the observation of spore formation. If meiotic divisions are observed, it confirms that haloid cells do indeed form spores through meiosis.

While not all haloid cells may follow the same reproductive pathway, evidence strongly suggests that meiosis is a key mechanism for spore formation in many species, particularly within the green algal group. This process ensures genetic diversity and is essential for the long-term survival of these organisms. For those studying or working with haloid cells, understanding this aspect of their biology provides valuable insights into their life cycle and reproductive strategies. By focusing on specific examples like *Chara* and employing observational techniques, one can definitively determine whether meiosis is involved in spore formation, contributing to a broader understanding of algal biology.

Can Coliforms Survive and Spore in Extreme Environmental Conditions?

You may want to see also

Spore Formation Mechanisms: Exploring how spores are formed in haloid cells, if applicable

Haloid cells, typically associated with certain algae and fungi, exhibit unique reproductive strategies, but their ability to form spores via meiosis is a nuanced topic. Unlike well-known spore-forming organisms like ferns or mushrooms, haloid cells primarily engage in asexual reproduction through binary fission or budding. However, in specific environmental conditions—such as nutrient depletion or desiccation—some haloid cells may undergo a modified form of meiosis to produce resilient spores. This process, though rare, involves genetic recombination and reduction division, resulting in spores capable of surviving harsh conditions until favorable growth conditions return.

To explore spore formation in haloid cells, consider the following steps. First, identify the species of haloid cell under study, as not all are capable of sporulation. Second, induce stress conditions in a controlled environment, such as reducing nutrient availability or increasing salinity. Monitor cellular changes using microscopy and genetic markers to detect signs of meiosis, such as chromosome pairing or sporulation-specific gene expression. Document the formation of spore-like structures and test their viability under various conditions to confirm their role as survival mechanisms.

A comparative analysis reveals that while haloid cells share some sporulation traits with fungi, their mechanisms differ significantly. Fungal spores, for instance, are often produced in specialized structures like sporangia, whereas haloid cells may form spores directly within the cell wall. Additionally, fungal spores typically result from meiosis followed by mitosis, whereas haloid cells may bypass traditional meiosis, opting for a simplified reduction division. This distinction highlights the adaptability of haloid cells in response to environmental pressures.

Practical tips for studying haloid cell sporulation include maintaining a sterile environment to avoid contamination, using time-lapse microscopy to capture the dynamic process, and employing molecular techniques like PCR to track gene activity. For educators or researchers, incorporating hands-on experiments with haloid cells can illustrate the diversity of reproductive strategies in microorganisms. While not all haloid cells form spores via meiosis, understanding their mechanisms provides valuable insights into microbial survival and evolution.

Botulism Spores Survival: Can They Thrive Without Moisture?

You may want to see also

Haloid Cell Life Cycle: Analyzing the role of meiosis in haloid cell reproduction

Haloid cells, a specialized type of cell found in certain organisms, exhibit a unique reproductive strategy that hinges on the process of meiosis. Unlike typical somatic cells, which divide through mitosis to produce genetically identical copies, haloid cells undergo meiosis to generate spores—a critical step in their life cycle. This process ensures genetic diversity, a key factor in the survival and adaptation of species in changing environments. Meiosis, with its two rounds of cell division and genetic recombination, is the cornerstone of haloid cell reproduction, enabling the formation of spores that can withstand harsh conditions and disperse to new habitats.

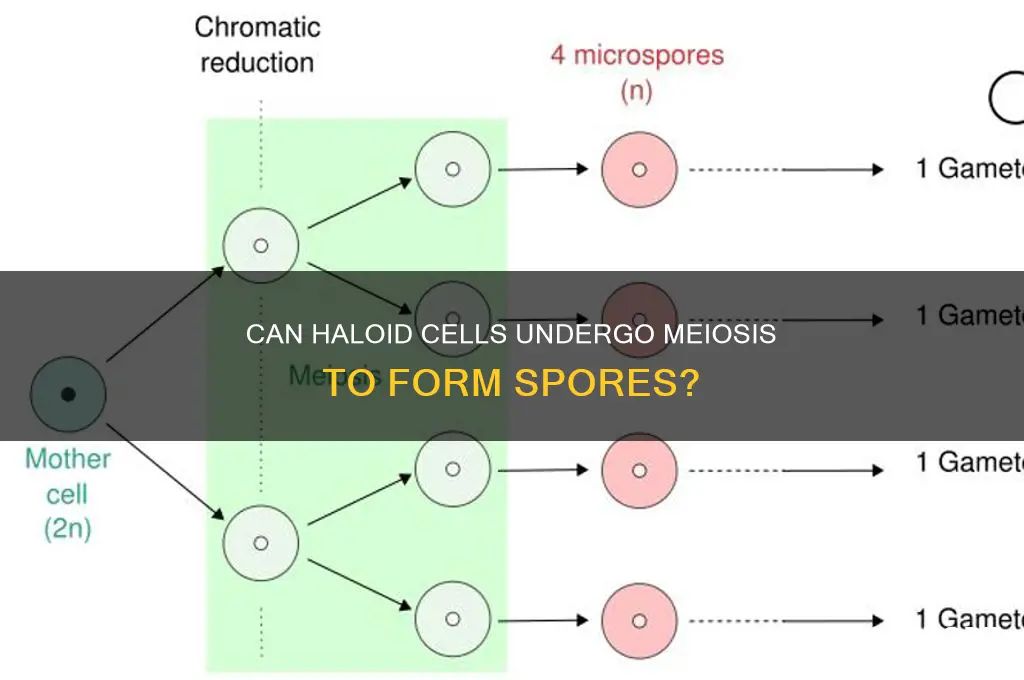

To understand the role of meiosis in haloid cell reproduction, consider the steps involved. First, a diploid haloid cell replicates its DNA, followed by two successive divisions: meiosis I and meiosis II. During meiosis I, homologous chromosomes segregate, reducing the chromosome number by half. Meiosis II then divides the sister chromatids, resulting in four haploid cells. These cells develop into spores, each genetically distinct due to crossing over during prophase I. This genetic shuffling is essential for haloid cells, as it allows spores to inherit a mix of traits from both parent cells, enhancing their ability to thrive in diverse environments.

A comparative analysis of haloid cell meiosis versus mitosis highlights its significance. While mitosis produces clones, meiosis fosters diversity—a critical advantage for haloid cells, which often inhabit unpredictable ecosystems. For instance, in algae species containing haloid cells, spores formed through meiosis can remain dormant for extended periods, germinating only when conditions are favorable. This adaptability contrasts sharply with mitotic divisions, which are more suited to stable environments. Practical applications of this knowledge include optimizing algal cultivation techniques, where inducing meiosis in haloid cells could enhance strain diversity and resilience.

Despite its advantages, the meiotic process in haloid cells is not without challenges. Errors during chromosome segregation or recombination can lead to non-viable spores, reducing reproductive success. Additionally, the energy cost of meiosis is higher than mitosis, requiring haloid cells to allocate significant resources to this process. Researchers studying haloid cell life cycles often focus on mitigating these risks through genetic manipulation or environmental control. For example, maintaining optimal nutrient levels (e.g., phosphorus and nitrogen concentrations) can support healthy meiosis, while temperature regulation (ideally between 20–25°C) minimizes stress on dividing cells.

In conclusion, meiosis plays a pivotal role in the haloid cell life cycle by enabling spore formation and genetic diversity. This process, while complex and resource-intensive, equips haloid cells with the adaptability needed to survive in dynamic environments. By analyzing the mechanics and implications of meiosis in haloid cells, scientists can unlock new strategies for conservation, agriculture, and biotechnology. Whether studying algal blooms or developing resilient crop strains, understanding this unique reproductive mechanism offers valuable insights into the interplay between genetics and environmental adaptation.

Mastering Morel Mushroom Cultivation: A Guide to Planting Spores

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Comparative Sporulation Processes: Comparing haloid cell sporulation with other organisms' methods

Haloid cells, found in certain algae like *Vaucheria*, undergo a unique sporulation process that contrasts sharply with methods seen in fungi, plants, and bacteria. Unlike the meiotic spore formation in fungi, where haploid spores are produced directly from a diploid zygote, haloid cells form spores through a process called zoosporulation. These zoospores are motile, flagellated cells that develop within the haloid cell before being released to disperse and grow into new individuals. This method bypasses the traditional meiotic reduction division, instead relying on mitotic divisions for proliferation. In contrast, fungal sporulation, such as in *Aspergillus*, involves meiosis to produce genetically diverse spores, ensuring adaptability in changing environments.

Consider the sporulation of *Bacillus subtilis*, a bacterium that forms endospores as a survival mechanism. Unlike haloid cells, which produce motile zoospores, bacterial endospores are dormant, highly resistant structures formed within the vegetative cell. This process does not involve meiosis but rather a specialized form of cell differentiation. Endospores can withstand extreme conditions, such as heat and radiation, whereas haloid cell zoospores are adapted for immediate dispersal and growth in aqueous environments. The distinct purposes of these spores—survival versus rapid colonization—highlight the evolutionary divergence in sporulation strategies.

In plants, sporulation occurs in the life cycle of ferns and mosses, where spores are produced via meiosis in sporangia. These spores are haploid and germinate into gametophytes, which then undergo sexual reproduction. Haloid cell sporulation, however, does not involve a haploid-diploid alternation of generations. Instead, zoospores are produced asexually and directly develop into new thalli. This simplicity in haloid cell sporulation contrasts with the complex life cycles of plants, where meiosis and fertilization are integral to spore formation and development.

To compare these processes practically, observe the following: haloid cell zoospores require a moist environment for motility and growth, while fungal spores often disperse via air and can remain dormant for years. Bacterial endospores are triggered to form under nutrient deprivation, whereas haloid cell sporulation is part of the organism’s reproductive cycle. For researchers, understanding these differences can guide experimental conditions—for instance, maintaining humidity for haloid cell cultures or inducing stress for bacterial endospore formation.

In conclusion, haloid cell sporulation stands apart from other organisms’ methods due to its asexual, motile zoospores and lack of meiotic involvement. While fungi, bacteria, and plants employ sporulation for genetic diversity, survival, or life cycle progression, haloid cells prioritize rapid dispersal and colonization. This comparative analysis underscores the diversity of sporulation strategies across kingdoms and their adaptations to specific ecological niches.

Can C. Diff Tests Detect Spores? Unraveling Diagnostic Accuracy

You may want to see also

Genetic Basis of Sporulation: Investigating genes involved in haloid cell spore development via meiosis

Haloid cells, a specialized cell type in certain fungi and algae, undergo a remarkable transformation during sporulation, a process critical for survival and propagation. Central to this transformation is meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, producing haploid spores. However, the genetic mechanisms governing this process remain largely unexplored. Recent advances in genomic sequencing and gene editing tools have opened new avenues to investigate the genes involved in haloid cell spore development via meiosis. By identifying and characterizing these genes, researchers can unravel the intricate regulatory networks that control sporulation, offering insights into evolutionary biology, biotechnology, and potential applications in agriculture and medicine.

To begin investigating the genetic basis of sporulation in haloid cells, researchers typically employ a combination of forward and reverse genetics approaches. Forward genetics involves screening for mutants with defects in sporulation, followed by mapping and cloning of the responsible genes. For instance, in the model fungus *Neurospora crassa*, mutations in the *mat* locus have been shown to disrupt meiosis and spore formation. Reverse genetics, on the other hand, targets specific genes of interest for knockout or overexpression studies. CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized this process, allowing precise editing of haloid cell genomes. A practical tip for researchers is to start with a well-characterized model organism, such as *Chlamydomonas reinhardtii*, where genetic tools and resources are readily available, before moving to less-studied species.

One critical aspect of sporulation is the temporal and spatial regulation of gene expression. Key regulatory genes, such as those encoding transcription factors, often act as master switches that activate or repress entire pathways. For example, the *SPO11* gene, conserved across eukaryotes, initiates meiosis by introducing double-strand breaks in DNA. In haloid cells, homologs of *SPO11* and downstream repair genes must be tightly regulated to ensure accurate chromosome segregation and spore viability. Dosage effects are also crucial; overexpression of certain genes, such as those involved in spore wall synthesis, can lead to malformed spores, while underexpression may result in failure to complete sporulation. Researchers should carefully titrate gene expression levels using inducible promoters to study these effects.

Comparative genomics provides another powerful tool for identifying genes involved in haloid cell sporulation. By comparing the genomes of species that undergo meiosis-driven sporulation with those that do not, conserved gene clusters can be identified as potential candidates. For instance, a comparative study between *Volvox carteri* and *Chlamydomonas reinhardtii* revealed shared genes involved in flagellar development, which are also critical for spore dispersal. Phylogenetic analysis can further refine these candidates, highlighting genes that have co-evolved with the sporulation process. This approach not only identifies functional genes but also sheds light on the evolutionary history of sporulation mechanisms.

Finally, the practical applications of understanding haloid cell sporulation genes are vast. In agriculture, manipulating sporulation genes in algae could enhance biofuel production or improve crop resilience through symbiotic relationships. In medicine, insights into spore development could inform strategies to combat fungal pathogens that rely on sporulation for transmission. For instance, targeting meiosis-specific genes in *Aspergillus fumigatus* could disrupt its life cycle, offering a novel antifungal approach. To maximize the impact of this research, interdisciplinary collaboration between geneticists, bioinformaticians, and applied scientists is essential. By integrating genetic insights with practical applications, the study of haloid cell sporulation genes holds promise for addressing some of the most pressing challenges in biotechnology and beyond.

The Last of Us: Unveiling the Truth About Spores in the Show

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, ha loid cells (haploid cells) do not form spores by meiosis. Spores in organisms like fungi and plants are typically formed by meiosis from diploid cells, not haploid cells.

No, ha loid cells do not undergo meiosis to produce spores. Meiosis is a process that occurs in diploid cells to produce haploid spores or gametes.

Yes, haploid cells can directly form spores through mitosis or other asexual processes, but this is not the same as spore formation via meiosis, which requires a diploid precursor.

No, meiosis is not necessary for ha loid cells to become spores. Since they are already haploid, they can form spores through mitosis or other asexual mechanisms, not meiosis.