Fungal spores are primarily known for their role in asexual reproduction, allowing fungi to disperse and colonize new environments efficiently. However, certain fungal species also utilize spores for sexual reproduction, a process that enhances genetic diversity and adaptability. In these cases, specialized spores, such as asci or basidiospores, are produced following the fusion of compatible haploid cells, resulting in the formation of a diploid zygote. This sexual cycle, known as the teleomorph stage, is crucial for the long-term survival and evolution of fungi, particularly in changing or challenging environments. Understanding the dual role of fungal spores in both asexual and sexual reproduction provides valuable insights into fungal biology and their ecological significance.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Role of Fungal Spores | Fungal spores can indeed be involved in sexual reproduction, but not all spores serve this purpose. |

| Types of Spores | - Sexual Spores: Zygospores, ascospores, and basidiospores are formed through sexual reproduction (meiosis). - Asexual Spores: Conidia, sporangiospores, and others are produced asexually (mitosis) and do not directly contribute to sexual reproduction. |

| Sexual Reproduction Process | Involves the fusion of haploid cells (e.g., gametangia) from compatible individuals, followed by meiosis to form sexual spores. |

| Examples of Fungi | - Zygomycetes: Produce zygospores via sexual reproduction. - Ascomycetes: Form ascospores in asci. - Basidiomycetes: Produce basidiospores on basidia. |

| Function of Sexual Spores | Ensure genetic diversity, aid in survival under harsh conditions, and facilitate dispersal. |

| Asexual vs. Sexual Spores | Asexual spores are for rapid multiplication, while sexual spores are for genetic recombination and long-term survival. |

| Environmental Triggers | Sexual spore formation is often induced by environmental cues like nutrient scarcity, stress, or specific mating signals. |

| Genetic Diversity | Sexual reproduction via spores increases genetic variation, enhancing adaptability to changing environments. |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Spores are lightweight and can be dispersed by wind, water, or animals, aiding in colonization of new habitats. |

| Ecological Importance | Sexual spores play a crucial role in fungal life cycles, ecosystem dynamics, and biodiversity. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Fungal spore types and their roles in sexual reproduction

- Mechanisms of spore fusion during sexual reproduction in fungi

- Environmental triggers for spore-mediated sexual reproduction in fungi

- Genetic diversity resulting from fungal spore sexual reproduction

- Comparative analysis of asexual vs. sexual spore reproduction in fungi

Fungal spore types and their roles in sexual reproduction

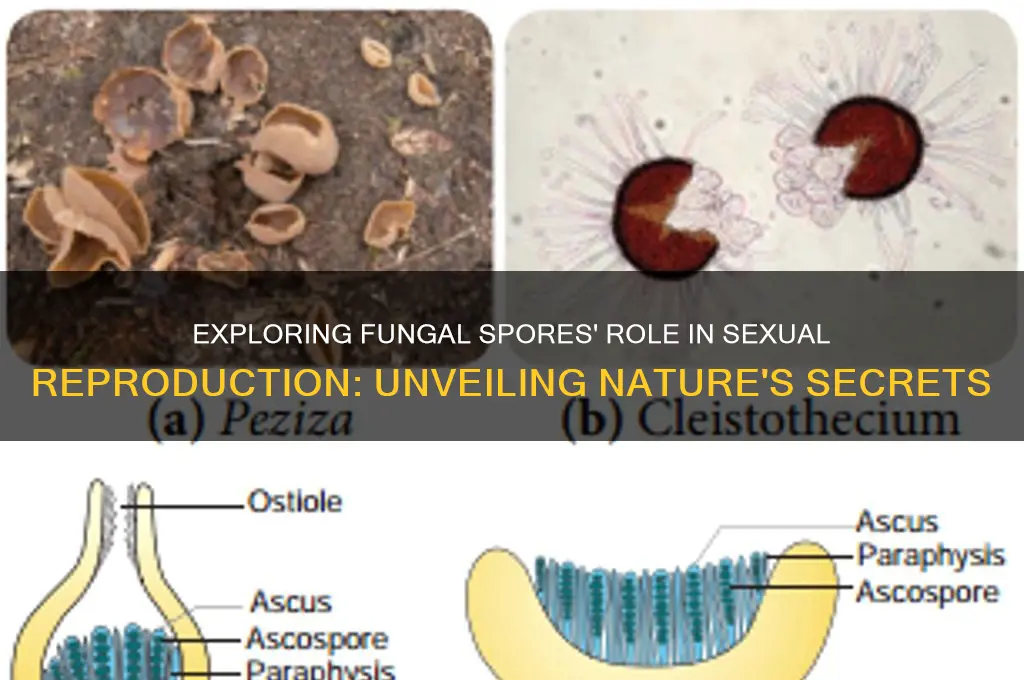

Fungi employ a diverse array of spore types to facilitate sexual reproduction, each tailored to specific environmental and biological needs. Among these, ascospores and basidiospores are the most prominent. Ascospores, produced within sac-like structures called asci, are characteristic of the Ascomycota phylum. These spores form following the fusion of haploid cells (gametes) and a subsequent meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity. Basidiospores, on the other hand, are produced by Basidiomycota and develop on club-shaped structures called basidia. Both spore types are ejected into the environment, where they disperse and germinate under favorable conditions, initiating new fungal colonies.

Consider the lifecycle of the common baker’s yeast, *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, an Ascomycota species. Under nutrient-limited conditions, haploid cells of opposite mating types (a and α) fuse to form a diploid zygote. This zygote then undergoes meiosis, producing four haploid ascospores within an ascus. These ascospores are not only resilient but also genetically diverse, enhancing the species’ adaptability. In contrast, mushrooms (Basidiomycota) release basidiospores from gills or pores, often in vast quantities—a single mushroom can release billions of spores daily. This high output increases the likelihood of successful dispersal and colonization, even in competitive environments.

While ascospores and basidiospores dominate discussions of fungal sexual reproduction, other spore types play specialized roles. Zygospores, formed by the fusion of hyphae in Zygomycota, are thick-walled and highly resistant to harsh conditions, serving as survival structures. Oospores, produced by Oomycota (often classified separately from true fungi), are similarly durable and function as long-term storage units for genetic material. These spores highlight the adaptability of fungi, with each type evolved to thrive in specific ecological niches, from soil to decaying wood.

Practical applications of fungal spores in sexual reproduction extend beyond biology. For instance, in agriculture, understanding spore dispersal mechanisms helps in managing fungal pathogens like *Botrytis cinerea*, which causes gray mold in crops. By disrupting spore release or germination, farmers can mitigate disease spread. Similarly, in biotechnology, ascospores of *Aspergillus* species are harnessed for enzyme production, while basidiospores of edible mushrooms are cultivated for food. Knowing the unique traits of each spore type enables targeted interventions, whether for control or exploitation.

In conclusion, fungal spore types are not merely reproductive units but sophisticated tools for survival and adaptation. Ascospores, basidiospores, zygospores, and oospores each fulfill distinct roles, reflecting the diversity of fungal lifecycles. By studying these spores, scientists and practitioners can unlock new strategies for managing fungi in agriculture, medicine, and industry. Whether dispersing genetic diversity or enduring extreme conditions, these spores underscore the ingenuity of fungal reproduction.

Natural Ways to Eliminate Airborne Mold Spores in Your Home

You may want to see also

Mechanisms of spore fusion during sexual reproduction in fungi

Fungal spores are not merely agents of dispersal; they are also key players in sexual reproduction, a process that ensures genetic diversity and adaptability. Among the diverse fungal species, spore fusion is a critical mechanism that facilitates the union of haploid nuclei, leading to the formation of a diploid zygote. This process, known as karyogamy, is a cornerstone of sexual reproduction in fungi, enabling them to thrive in various environments.

Consider the intricate dance of spore fusion in Basidiomycetes, a fungal group that includes mushrooms and rusts. In these organisms, two haploid hyphae, known as compatible mating types, must come into contact to initiate the process. The fusion of their cell walls and membranes is mediated by specialized structures called fusion cells or gametangia. For instance, in the model fungus *Coprinopsis cinerea*, pheromones play a crucial role in recognizing compatible partners, ensuring that only genetically distinct individuals mate. This specificity is vital for maintaining genetic diversity, as it prevents inbreeding and promotes the recombination of genetic material.

The actual fusion of spores involves a series of highly regulated steps. First, the cell walls of the fusing spores are degraded locally, allowing the plasma membranes to come into close proximity. This is followed by the merging of these membranes, creating a continuous cytoplasmic bridge between the two cells. The nuclei then migrate toward each other through this bridge, eventually fusing to form a diploid nucleus. In Ascomycetes, such as *Neurospora crassa*, this process is further refined by the formation of a specialized structure called the ascus, which encapsulates the developing spores and ensures their protection during karyogamy.

Practical insights into spore fusion mechanisms have significant implications for biotechnology and agriculture. For example, understanding how fungi like *Trichoderma* species fuse their spores can inform the development of biofungicides, where genetically diverse strains are engineered to combat plant pathogens more effectively. Similarly, in the brewing industry, knowledge of yeast spore fusion (though yeasts are not typically considered fungi in modern taxonomy, they share similar reproductive mechanisms) helps optimize fermentation processes by ensuring the production of robust, genetically varied populations.

In conclusion, the mechanisms of spore fusion during sexual reproduction in fungi are a testament to the complexity and elegance of nature’s designs. From pheromone-mediated recognition to the precise orchestration of nuclear fusion, these processes ensure genetic diversity and adaptability. By studying these mechanisms, scientists can harness their potential for applications ranging from disease control to industrial fermentation, underscoring the practical value of understanding fungal biology.

Yeast Spore Germination: Unveiling the Intricate Process of Awakening

You may want to see also

Environmental triggers for spore-mediated sexual reproduction in fungi

Fungal spores are not merely agents of dispersal; they are also pivotal in sexual reproduction, a process triggered by specific environmental cues. These triggers ensure that fungi reproduce under optimal conditions, maximizing survival and genetic diversity. Understanding these cues is essential for both ecological research and practical applications, such as controlling fungal pathogens in agriculture.

Light and Temperature: The Dual Regulators

Light and temperature act as primary environmental signals for spore-mediated sexual reproduction in fungi. For instance, the model fungus *Neurospora crassa* requires specific light wavelengths, particularly in the blue spectrum (450–470 nm), to initiate sexual development. This photoreception is mediated by the protein White Collar-1 (WC-1), which activates carotenoid biosynthesis, a precursor to sexual structures. Temperature also plays a critical role; many basidiomycetes, like *Coprinopsis cinerea*, form fruiting bodies only within a narrow temperature range (15–25°C). Deviations from this range inhibit sexual reproduction, highlighting the precision required for these processes.

Nutrient Availability: A Balancing Act

Nutrient scarcity often triggers sexual reproduction in fungi, a strategy to survive adverse conditions. For example, *Aspergillus nidulans* undergoes sexual development when nitrogen levels are low, a response regulated by the transcription factor NsdD. Conversely, excess nutrients can suppress sexual reproduction, as seen in *Fusarium graminearum*, where high nitrogen concentrations favor asexual spore production. This nutrient-dependent switch ensures fungi allocate resources efficiently, prioritizing survival over reproduction when necessary.

Physical Contact and Chemical Signals: The Role of Quorum Sensing

Physical contact between compatible fungal strains and chemical signaling molecules, such as hormones or pheromones, are critical triggers for sexual reproduction. In *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, mating occurs when cells of opposite mating types (a and α) secrete pheromones that bind to receptors on the opposite strain, initiating cell fusion. Similarly, in filamentous fungi like *Podospora anserina*, chemical signals released by compatible strains induce the formation of sexual structures. These mechanisms ensure that sexual reproduction occurs only when compatible partners are present, optimizing genetic recombination.

Practical Implications and Control Strategies

Understanding these environmental triggers has practical applications, particularly in agriculture. For instance, manipulating light exposure or temperature in crop fields can disrupt the sexual reproduction of pathogens like *Magnaporthe oryzae*, reducing disease incidence. Similarly, nutrient management strategies, such as maintaining optimal nitrogen levels, can suppress sexual reproduction in fungi like *Fusarium*, limiting their ability to produce resilient spores. By leveraging these triggers, farmers and researchers can develop targeted control measures, reducing reliance on chemical fungicides and promoting sustainable practices.

In summary, environmental triggers for spore-mediated sexual reproduction in fungi are diverse and finely tuned, ensuring reproductive success under optimal conditions. From light and temperature to nutrient availability and chemical signals, these cues orchestrate a complex process with significant ecological and practical implications. Mastering these mechanisms opens new avenues for fungal control and conservation, underscoring the importance of environmental factors in fungal biology.

Tracking Black Non-Toxic Spores: Can They Enter Your Home?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Genetic diversity resulting from fungal spore sexual reproduction

Fungal spores are not merely agents of dispersal; they are pivotal in the sexual reproduction of fungi, driving genetic diversity. Unlike asexual spores, which clone the parent organism, sexual spores arise from the fusion of gametes, combining genetic material from two individuals. This process, known as karyogamy, results in offspring with unique genetic combinations, enhancing the species' adaptability to changing environments. For instance, in *Neurospora crassa*, a model fungus, sexual reproduction via spores introduces genetic recombination, allowing populations to evolve resistance to toxins or exploit new nutrient sources.

Consider the practical implications of this genetic diversity. In agriculture, fungal pathogens like *Fusarium* or *Magnaporthe* can rapidly evolve to overcome crop resistance genes. Sexual spore reproduction accelerates this process by shuffling alleles, creating variants that may bypass host defenses. Farmers and breeders must therefore monitor fungal populations and rotate resistance strategies to mitigate risks. Conversely, beneficial fungi, such as mycorrhizal species, use sexual spores to adapt to soil changes, improving nutrient uptake for plants. Understanding these dynamics can inform sustainable farming practices, such as promoting diverse fungal communities to enhance soil health.

To harness or control fungal genetic diversity, one must first identify the conditions triggering sexual reproduction. Many fungi require specific environmental cues, such as temperature shifts or nutrient scarcity, to initiate spore formation. For example, *Aspergillus nidulans* produces sexual spores (ascospores) only under light exposure and high carbon-to-nitrogen ratios. Manipulating these conditions in controlled settings—like laboratories or greenhouses—can either suppress pathogenic fungi or encourage beneficial strains. A practical tip: for mushroom cultivators, alternating periods of darkness and light can stimulate sexual spore development in species like *Coprinopsis cinerea*, increasing genetic variability in subsequent generations.

Comparing asexual and sexual spore reproduction highlights the trade-offs in genetic diversity. Asexual spores, produced via mitosis, are efficient for rapid colonization but limit adaptability. Sexual spores, however, introduce mutations and recombinations, fostering resilience. This distinction is critical in medical contexts: antifungal drug resistance in pathogens like *Candida albicans* often arises from sexual recombination, complicating treatment. Clinicians and researchers must prioritize therapies targeting conserved fungal pathways to minimize resistance evolution. Meanwhile, in biotechnology, sexual spores are exploited to engineer fungi with desirable traits, such as improved enzyme production for biofuel synthesis.

In conclusion, fungal spore sexual reproduction is a double-edged sword, offering both challenges and opportunities. By understanding the mechanisms and conditions driving genetic diversity, stakeholders can strategically manage fungal populations. Whether combating pathogens, enhancing agriculture, or advancing biotechnology, the key lies in leveraging sexual spores' inherent capacity for innovation. Practical steps include monitoring environmental triggers, promoting diverse fungal ecosystems, and integrating genetic knowledge into applied strategies. This nuanced approach ensures that fungi's reproductive prowess serves, rather than hinders, human endeavors.

Are Fungal Spores Haploid? Unraveling the Genetics of Fungi

You may want to see also

Comparative analysis of asexual vs. sexual spore reproduction in fungi

Fungi employ two primary reproductive strategies: asexual and sexual spore production. Each method serves distinct ecological and evolutionary purposes, shaped by environmental pressures and genetic diversity needs. Asexual reproduction, via spores like conidia or budding, allows rapid proliferation in stable, resource-rich environments. For instance, *Aspergillus* fungi disperse conidia to colonize new substrates swiftly. In contrast, sexual reproduction, involving meiosis and spore types like asci or basidiospores, occurs under stress or nutrient depletion, promoting genetic recombination. This duality ensures fungal survival across fluctuating conditions, from decomposing wood to human hosts.

Consider the lifecycle of *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, a model fungus. Under nutrient abundance, it buds asexually, doubling every 90 minutes. However, upon nitrogen depletion, it undergoes sexual reproduction, forming resilient asci spores. This shift underscores the trade-off: asexual methods prioritize speed and efficiency, while sexual reproduction enhances adaptability through genetic diversity. For cultivators, manipulating these conditions—such as adjusting nutrient levels in fermentation—can control reproductive outcomes, optimizing yield or strain robustness.

From an evolutionary standpoint, sexual reproduction mitigates the risks of clonal vulnerability. Asexual spores, genetically identical to the parent, thrive in predictable environments but falter against novel threats like antifungals. Sexual spores, genetically diverse, offer a hedge against such challenges. For example, *Cryptococcus neoformans* employs sexual reproduction to evade host immune responses, a critical factor in its pathogenicity. This highlights the strategic advantage of sexual spores in dynamic or hostile ecosystems, where adaptability trumps rapid replication.

Practically, understanding these mechanisms informs fungal management. In agriculture, asexual spores of *Trichoderma* are deployed as biocontrol agents for their rapid colonization of plant roots. Conversely, preventing sexual reproduction in pathogens like *Fusarium* limits their ability to evolve resistance. For hobbyists cultivating mushrooms, inducing sexual reproduction in *Agaricus bisporus* via controlled light and humidity yields genetically diverse, disease-resistant strains. Thus, tailoring reproductive strategies to context—whether in labs, fields, or kitchens—maximizes fungal utility.

In summary, asexual and sexual spore reproduction in fungi represent complementary survival tools. Asexual methods excel in stability, while sexual strategies thrive in adversity. By dissecting these mechanisms, we gain actionable insights: from optimizing industrial fermentation to combating fungal diseases. The key lies in recognizing when to harness speed versus diversity, a principle as applicable to microbial ecology as it is to applied mycology.

Are Mold Spores Microscopic? Unveiling the Hidden World of Mold

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, certain fungal spores, such as zygospores, ascospores, and basidiospores, are produced as a result of sexual reproduction in fungi. These spores form after the fusion of compatible haploid cells (gametes) and play a key role in the sexual life cycle of fungi.

No, not all fungal spores are produced sexually. Many fungi also produce asexual spores, such as conidia or sporangiospores, which are formed through mitosis without the involvement of gamete fusion. These asexual spores are used for rapid dispersal and survival in unfavorable conditions.

Sexual spores in fungi serve to promote genetic diversity, which helps fungal populations adapt to changing environments. They also allow fungi to survive harsh conditions, as sexual spores are often more resilient than asexual spores. Additionally, sexual reproduction ensures the long-term survival and evolution of fungal species.