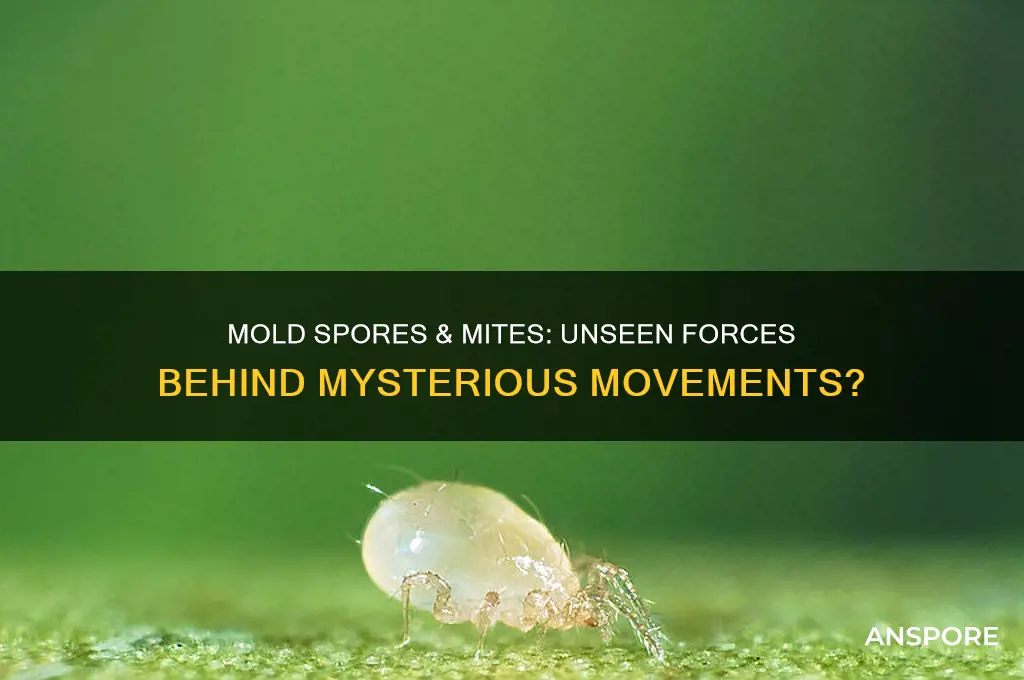

The intriguing question of whether mold spores and mites can cause objects to move delves into the intersection of biology, physics, and everyday observations. While mold spores and mites are microscopic organisms commonly found in various environments, their ability to generate movement is often misunderstood. Mold spores, being lightweight and airborne, can be carried by air currents, but they lack the physical mechanisms to directly move objects. Similarly, mites, tiny arthropods, primarily focus on feeding and reproduction rather than exerting force on inanimate objects. However, in certain conditions, the collective presence of these organisms can indirectly contribute to movement, such as when mold growth weakens materials or when mite activity disturbs lightweight particles. This raises fascinating questions about the subtle yet significant impact of microscopic life on the physical world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Mold Spores Movement | Mold spores themselves do not have the ability to move things. They are passive and rely on air currents, water, or physical contact for dispersal. |

| Mites Movement | Mites are tiny arthropods that can move independently. However, they do not have the capability to move objects significantly larger than themselves. |

| Collective Movement | Neither mold spores nor mites can collectively organize to move objects. Their movements are individual and not coordinated. |

| Physical Interaction | Mold spores and mites may indirectly cause movement by accumulating on surfaces, potentially affecting friction or weight, but this is not an active process. |

| Scientific Consensus | There is no scientific evidence to suggest that mold spores or mites can actively make things move. |

| Myth vs. Reality | Myths or misconceptions about mold spores or mites causing movement are not supported by biological or physical principles. |

| Environmental Impact | While mold and mites can impact health and materials, their role in causing physical movement of objects is negligible. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Mold Spores & Kinetic Energy: Can mold spores generate enough force to move objects

- Mites & Material Displacement: Do mites cause movement by burrowing or feeding

- Spores in Air Currents: Can airborne mold spores influence object movement via wind

- Microbial Motility: Do mold or mites exhibit movement that affects surrounding items

- Mechanisms of Displacement: How might mold spores or mites indirectly cause objects to move

Mold Spores & Kinetic Energy: Can mold spores generate enough force to move objects?

Mold spores, those microscopic fungi, are often associated with decay and health hazards, but could they also be tiny powerhouses of kinetic energy? The idea that mold spores might generate enough force to move objects seems far-fetched, yet nature is full of surprises. Consider the explosive force of a mushroom’s spore discharge, which can propel spores at speeds up to 10 meters per second. While this mechanism is designed for dispersal, it raises the question: could such forces, under specific conditions, translate into observable movement of objects?

To explore this, let’s break down the mechanics. Mold spores release kinetic energy during sporulation, but the force is typically directed outward for propagation. For context, a single spore’s discharge force is minuscule, measured in nanonewtons. However, collective action could theoretically amplify this. Imagine a dense colony of mold spores releasing simultaneously—could their combined energy nudge a lightweight object, like a grain of sand or a piece of dust? The answer lies in scale and environment. In a controlled setting, such as a sealed chamber with optimized humidity and temperature, the cumulative force might achieve minor movement, though this remains speculative.

Practical applications of this phenomenon are limited but intriguing. For instance, in microengineering, harnessing spore discharge could inspire designs for tiny, self-propelled devices. However, challenges abound. Mold spores are unpredictable, and their energy output is inconsistent. Additionally, the ethical and health implications of manipulating mold in such ways cannot be ignored. Exposure to mold spores can trigger allergies or respiratory issues, making experimentation risky without proper safeguards.

In conclusion, while mold spores do generate kinetic energy, their ability to move objects is constrained by their individual weakness and the unpredictability of their collective behavior. This concept, though fascinating, remains a curiosity rather than a practical tool. For now, mold spores are better left to their natural role in ecosystems, where their energy serves the purpose of survival and propagation, not object manipulation.

Hidden Dangers: Mold Spores Lurking in Your Carpet?

You may want to see also

Mites & Material Displacement: Do mites cause movement by burrowing or feeding?

Mites, microscopic arthropods, are often associated with dust, skin, and plant matter, but their potential to cause material displacement is a lesser-known phenomenon. These tiny creatures, measuring between 0.1 to 0.5 millimeters, can inhabit various environments, from household dust to stored products. When considering their impact on movement, it’s essential to examine their behaviors: burrowing and feeding. For instance, stored-product mites, such as *Tyrophagus putrescentiae*, are known to infest grains, flour, and pet food. As they feed, they create pathways through the material, potentially altering its structure and causing subtle shifts in position. This raises the question: can the cumulative effect of numerous mites lead to noticeable material displacement?

To investigate this, let’s break down the mechanics of mite activity. Burrowing mites, like those in the family Acaridae, create tunnels in organic matter, such as decaying wood or plant debris. This process can loosen the material, making it more susceptible to movement when disturbed. Feeding mites, on the other hand, consume particles from the surface or within the material, leaving behind frass (excrement) and silk threads. While individual mites have minimal impact, colonies can number in the thousands, amplifying their collective effect. For example, in a 1-kilogram bag of infested flour, a population of 10,000 mites could significantly alter the texture and density of the material over time, potentially causing it to settle or shift when handled.

Practical observations support the idea that mites contribute to material displacement, though the extent depends on factors like mite density, material type, and environmental conditions. In museums, for instance, mites infesting organic artifacts like textiles or paper can weaken the material’s structure, making it more prone to movement during handling or display. To mitigate this, conservators often recommend storing such items in sealed containers with silica gel to reduce humidity, which discourages mite proliferation. For households dealing with mite-infested pantry items, the solution is straightforward: discard contaminated products, clean storage areas thoroughly, and store new items in airtight containers.

Comparatively, while mold spores are primarily associated with decomposition and staining, mites actively interact with their environment through physical manipulation. Unlike mold, which grows in place, mites move through materials, leaving behind tangible evidence of their presence. This distinction highlights the unique role of mites in material displacement. For those studying or managing mite infestations, monitoring population levels is key. Simple traps, such as placing sticky tape near infested areas, can help assess mite activity. If populations exceed 5–10 mites per trap in a 24-hour period, intervention is likely necessary.

In conclusion, mites can indeed cause material displacement through their burrowing and feeding activities, particularly in high-density populations. While the movement may be subtle, it is measurable and can have practical implications, from household pantry management to museum conservation. Understanding the mechanics of mite behavior allows for targeted control measures, ensuring that these microscopic creatures do not inadvertently rearrange the world around them.

Understanding Spores: Haploid or Diploid? Unraveling the Genetic Mystery

You may want to see also

Spores in Air Currents: Can airborne mold spores influence object movement via wind?

Airborne mold spores, though microscopic, are not passive passengers in the atmosphere. These lightweight particles, typically ranging from 1 to 100 micrometers in size, are easily swept up by air currents. Their collective presence in high concentrations can influence the movement of small, lightweight objects. For instance, a thin sheet of paper or a feather placed in a mold-infested environment may exhibit subtle movements due to the combined force of spores and air currents. This phenomenon raises the question: can mold spores themselves, beyond their role as hitchhikers, contribute to the displacement of objects?

To understand this, consider the physics of air movement. Wind, a macroscopic force, is capable of moving objects by exerting pressure on their surfaces. Mold spores, while individually insignificant, can aggregate in dense clouds, particularly in damp, enclosed spaces. When these spore clouds are carried by wind, they add to the overall mass and momentum of the air current. In controlled environments, such as laboratory settings, researchers have observed that high concentrations of spores (e.g., 10,000 spores per cubic meter) can slightly amplify the force of a gentle breeze (1-2 mph), causing objects like pollen grains or fine dust particles to shift more noticeably.

However, the practical impact of mold spores on object movement is limited. For spores to significantly influence movement, their concentration would need to be extraordinarily high—far beyond typical household or outdoor levels. For example, a mold-infested basement might have spore counts of 500,000 per cubic meter, but even this density is insufficient to move objects larger than a grain of sand without a strong wind. Moreover, spores are not uniform in shape or weight, and their irregular distribution in air currents reduces their collective effect. Thus, while theoretically possible, the role of mold spores in object movement is negligible in most real-world scenarios.

For those concerned about mold-related movement, practical steps can mitigate risks. Maintaining indoor humidity below 50% discourages mold growth, reducing spore counts. Regularly cleaning air vents and using HEPA filters can capture spores before they accumulate. In extreme cases, professional mold remediation may be necessary to address high spore concentrations. While mold spores in air currents are unlikely to move household items, their presence remains a health concern, underscoring the importance of proactive mold management.

Detecting Botulism: Tests for Identifying Deadly Spore Presence

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Microbial Motility: Do mold or mites exhibit movement that affects surrounding items?

Mold spores and mites are often associated with decay and allergies, but their potential to induce movement in surrounding items is a lesser-known phenomenon. While neither mold spores nor mites possess muscular systems or limbs, their collective behavior and environmental interactions can lead to observable displacement of objects. For instance, mold colonies growing on surfaces can exert mechanical pressure as they expand, causing lightweight materials like paper or fabric to warp or shift. Similarly, the cumulative movement of mites, though microscopic, can create subtle vibrations or disturbances in their immediate environment, particularly in confined spaces such as storage containers or upholstery.

Analyzing the mechanisms behind this movement reveals a combination of biological and physical processes. Mold spores, once germinated, form hyphae—thread-like structures that grow in a network. As these hyphae penetrate and expand within a material, they can generate enough force to alter its shape or position. This is particularly evident in porous materials like wood or textiles, where the hyphae can act as micro-levers, prying apart fibers or cells. Mites, on the other hand, rely on their sheer numbers and constant motion. A single mite’s movement is negligible, but in infestations numbering in the thousands, their collective crawling can create a ripple effect, especially in fine powders or loose particles.

Practical implications of this microbial motility are noteworthy, especially in preservation and storage. For example, archivists must consider how mold growth can damage documents by causing them to curl or detach from bindings. To mitigate this, maintaining humidity levels below 50% and ensuring proper ventilation are critical steps. Similarly, museum conservators often use airtight enclosures to prevent mite infestations in organic artifacts, as their movement can displace pigments or weaken structural integrity. For homeowners, regularly inspecting stored items and using desiccants can prevent both mold and mite-induced damage.

Comparatively, while mold and mites both contribute to movement, their effects differ in scale and mechanism. Mold’s impact is more structural, often resulting in permanent deformation or degradation of materials. Mites, however, tend to cause transient disturbances, such as redistributing dust or powders, which can be more easily rectified. Understanding these distinctions allows for targeted interventions: antifungal treatments for mold-prone areas and pest control measures for mite-infested environments.

In conclusion, while mold spores and mites do not move in the conventional sense, their growth and activity can indeed cause surrounding items to shift or alter. By recognizing the specific ways these microorganisms interact with their environment, individuals can take proactive steps to protect valuable materials and maintain the integrity of stored goods. Whether through humidity control, regular inspections, or appropriate storage practices, addressing microbial motility is essential for preservation across various contexts.

Can Bellsprout Learn Spore? Exploring Pokémon Move Possibilities

You may want to see also

Mechanisms of Displacement: How might mold spores or mites indirectly cause objects to move?

Mold spores and mites, though microscopic, can indirectly trigger the movement of objects through a cascade of ecological and physical interactions. Consider the role of these organisms in decomposing organic materials. As mold spores colonize surfaces like wood or fabric, they secrete enzymes that break down complex structures, weakening the material's integrity. Over time, this degradation can cause objects to warp, crack, or fragment, leading to shifts in position. For instance, a mold-infested wooden board may bow under its own weight, sliding off a stack or tilting on a shelf. Similarly, mites feeding on fibers can cause textiles to thin or tear, allowing external forces like air currents to displace them more easily.

To understand this mechanism further, imagine a scenario where mold spores infiltrate a stack of old books in a damp basement. As the mold grows, it consumes the cellulose in the paper, reducing the books' structural stability. Coupled with the burrowing activity of mites, the pages become brittle and prone to detachment. When a slight vibration occurs—say, from a passing vehicle or a nearby appliance—the weakened books may topple or slide, demonstrating how these organisms indirectly facilitate movement through material degradation.

From a practical standpoint, preventing such displacement requires controlling the conditions that favor mold and mite proliferation. Maintain humidity levels below 50% using dehumidifiers, and ensure proper ventilation in storage areas. Regularly inspect susceptible materials, such as cardboard boxes or upholstered furniture, for early signs of infestation. For high-risk items, consider using airtight containers or desiccants to inhibit spore germination and mite survival. In cases of active infestation, remove affected objects promptly to prevent further spread and structural compromise.

Comparatively, the indirect movement caused by mold and mites contrasts with direct biological motion, such as that of mold's mycelial networks or mite locomotion. While these organisms do not physically push or pull objects, their transformative effects on materials create conditions where external forces can act more effectively. For example, a mite-infested rug may become light enough for a draft to lift its edge, or a mold-weakened picture frame might fall when its mounting hardware fails. This distinction highlights the importance of addressing the root cause—the infestation—rather than merely securing objects against movement.

In conclusion, mold spores and mites indirectly cause objects to move by compromising the structural integrity of materials through decomposition and feeding activities. By understanding these mechanisms, individuals can take proactive steps to mitigate risks, such as controlling environmental conditions and inspecting vulnerable items regularly. While these organisms do not directly displace objects, their presence creates a chain of events that can lead to noticeable movement, underscoring the need for preventive measures in susceptible environments.

Are Psilocybin Spores Illegal? Understanding the Legal Landscape

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, mold spores cannot cause objects to move. They are microscopic fungi that grow in damp environments but lack the physical capability to exert force or motion on objects.

No, dust mites are tiny insects that feed on dead skin cells and do not possess the strength or mechanism to move objects. Their presence is often unnoticed without magnification.

No, neither mold nor mites produce vibrations or movements. Any perceived motion is likely due to external factors like air currents, settling structures, or human error.