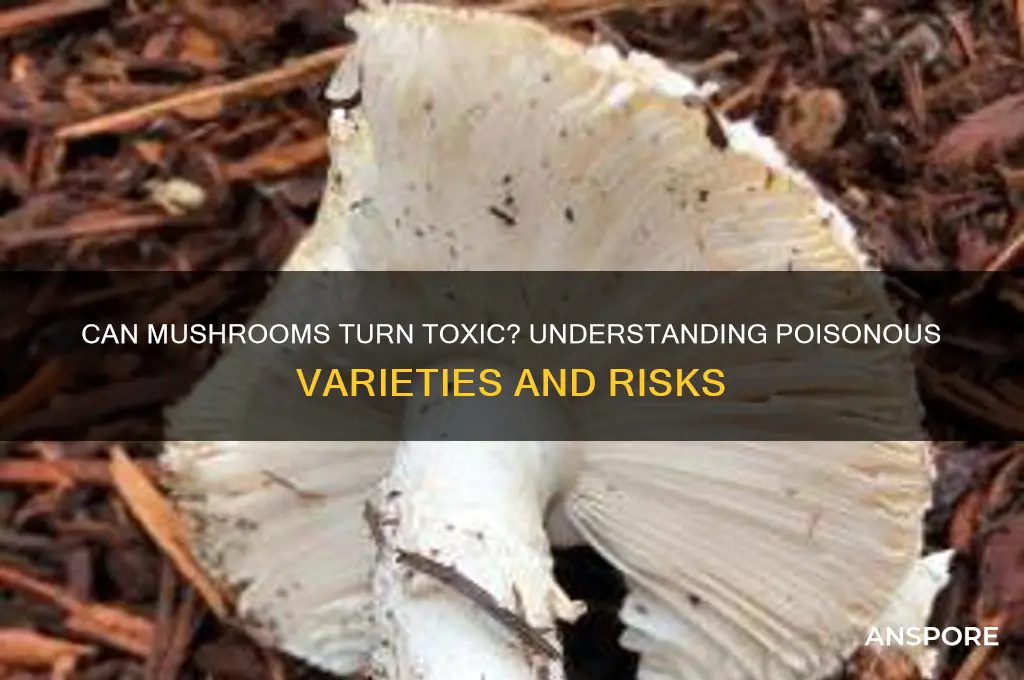

Mushrooms are a diverse group of fungi that can be both a culinary delight and a potential danger, as some species are highly toxic to humans. While many mushrooms are safe and even nutritious, others contain harmful compounds that can cause severe illness or even be fatal if ingested. The toxicity of mushrooms can vary widely, with symptoms ranging from mild gastrointestinal discomfort to organ failure, depending on the species and the amount consumed. Identifying edible mushrooms from poisonous ones requires careful examination of their physical characteristics, such as color, shape, and habitat, as well as knowledge of regional varieties. Misidentification is a common risk, making it crucial for foragers and enthusiasts to exercise caution and, when in doubt, consult expert guidance or avoid consumption altogether.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can mushrooms become poisonous? | Yes, some mushrooms can become poisonous under certain conditions. |

| Reasons for toxicity | 1. Species-specific toxins: Certain mushroom species naturally produce toxins (e.g., Amanita phalloides contains amatoxins). 2. Environmental factors: Mushrooms can absorb toxins from their surroundings, such as heavy metals or pollutants. 3. Misidentification: Edible mushrooms may be mistaken for toxic look-alikes. 4. Age and decomposition: Some mushrooms become toxic as they age or decompose. 5. Cooking and preparation: Improper cooking or storage can lead to toxin formation (e.g., trichothecene mycotoxins in moldy mushrooms). |

| Common toxic compounds | Amatoxins, orellanine, muscarine, ibotenic acid, and coprine. |

| Symptoms of poisoning | Gastrointestinal distress, liver/kidney failure, neurological symptoms, hallucinations, or death, depending on the toxin. |

| Prevention | Proper identification, sourcing from reputable suppliers, thorough cooking, and avoiding wild mushrooms unless an expert. |

| Treatment | Immediate medical attention, activated charcoal, supportive care, and, in severe cases, liver transplantation. |

| Notable toxic species | Death Cap (Amanita phalloides), Destroying Angel (Amanita bisporigera), Fool's Mushroom (Amanita verna), and Conocybe filaris. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Factors causing toxicity: Environmental conditions, species misidentification, and improper storage can turn mushrooms toxic

- Symptoms of poisoning: Nausea, vomiting, hallucinations, organ failure, and even death can result from toxic mushrooms

- Common poisonous species: Amanita, Galerina, and Cortinarius are among the most dangerous poisonous mushrooms

- Safe foraging practices: Proper identification, expert guidance, and avoiding unknown species prevent accidental poisoning

- Cooking and preparation: Some toxic mushrooms require specific preparation methods to neutralize toxins before consumption

Factors causing toxicity: Environmental conditions, species misidentification, and improper storage can turn mushrooms toxic

Mushrooms, often celebrated for their culinary and medicinal properties, can unexpectedly turn toxic under certain conditions. Environmental factors play a pivotal role in this transformation. For instance, mushrooms exposed to high levels of heavy metals, such as lead or mercury, in the soil can accumulate these toxins, making them unsafe for consumption. Similarly, pollution from industrial runoff or pesticides can contaminate mushrooms, rendering them poisonous. Even seemingly benign factors like excessive rainfall or drought can stress the fungi, leading to the production of harmful compounds. Understanding these environmental risks is crucial for foragers and cultivators alike, as it underscores the importance of sourcing mushrooms from clean, uncontaminated areas.

Misidentification of mushroom species is another critical factor that can lead to toxicity. The fungal kingdom is vast, with over 14,000 known mushroom species, many of which resemble one another. For example, the deadly Amanita phalloides (Death Cap) closely resembles the edible Paddy Straw mushroom, leading to fatal mistakes. Even experienced foragers can fall victim to this error, especially in regions where similar species coexist. To mitigate this risk, always cross-reference findings with multiple reliable guides, consult experts, and avoid consuming any mushroom unless 100% certain of its identity. Remember, when in doubt, throw it out—a small precaution that can save lives.

Improper storage of mushrooms can also introduce toxicity, often overlooked by enthusiasts. Fresh mushrooms are highly perishable and can spoil quickly, leading to the growth of harmful bacteria or molds. For instance, storing mushrooms in airtight containers or plastic bags can trap moisture, creating an ideal environment for bacterial growth. Instead, store them in paper bags or loosely wrapped in a damp cloth in the refrigerator, ensuring proper airflow. Additionally, avoid consuming mushrooms that show signs of sliminess, discoloration, or an off odor, as these are indicators of spoilage. Proper storage not only preserves freshness but also prevents the development of toxins that can cause foodborne illnesses.

To summarize, the toxicity of mushrooms is not always inherent but can arise from environmental contamination, misidentification, and improper handling. Foragers and consumers must remain vigilant, adopting practices such as sourcing from clean environments, accurately identifying species, and storing mushrooms correctly. By understanding these factors, one can safely enjoy the benefits of mushrooms while minimizing the risks associated with their consumption. After all, knowledge is the best defense against the hidden dangers lurking in the fungal world.

Mushroom Overdose Risks: Understanding Safe Consumption Limits and Effects

You may want to see also

Symptoms of poisoning: Nausea, vomiting, hallucinations, organ failure, and even death can result from toxic mushrooms

Mushrooms, often celebrated for their culinary and medicinal benefits, can also harbor deadly toxins. While many species are safe, others contain compounds like amatoxins, orellanine, or muscarine, which can cause severe poisoning. The symptoms of mushroom toxicity vary widely depending on the species ingested, but they often include nausea, vomiting, hallucinations, organ failure, and in extreme cases, death. Recognizing these symptoms early is crucial, as prompt medical intervention can be life-saving.

Nausea and vomiting are typically the first signs of mushroom poisoning, appearing within 6 to 24 hours after ingestion. These symptoms are the body’s attempt to expel the toxin but can lead to dehydration if severe. For instance, mushrooms containing amatoxins, such as the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), cause delayed gastrointestinal distress, often lulling victims into a false sense of security before more serious symptoms emerge. If you suspect poisoning, rehydration with oral electrolyte solutions can help, but medical attention is non-negotiable.

Hallucinations are another alarming symptom, commonly associated with psychoactive mushrooms like those containing psilocybin. However, toxic species such as the Fly Agaric (*Amanita muscaria*) can induce hallucinations, confusion, and delirium due to muscimol and ibotenic acid. These symptoms can be particularly dangerous in children or individuals with pre-existing mental health conditions. If hallucinations occur after mushroom ingestion, keep the person calm and in a safe environment while seeking emergency care.

Organ failure is a critical and often irreversible consequence of severe mushroom poisoning. Amatoxins, for example, target the liver and kidneys, leading to acute liver failure within 3 to 5 days. Orellanine, found in species like the Fool’s Webcap (*Cortinarius orellanus*), causes delayed kidney failure, sometimes weeks after ingestion. Early administration of activated charcoal, silibinin (a milk thistle extract), or even liver transplantation in extreme cases can mitigate damage. Monitoring liver and kidney function through blood tests is essential for diagnosis and treatment.

Death from mushroom poisoning is rare but not unheard of, particularly with species like the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*). Fatalities often result from delayed treatment or misidentification of toxic species. For example, the Death Cap is frequently mistaken for edible paddlestick mushrooms or straw mushrooms, especially in regions like North America and Europe. To avoid such tragedies, never consume wild mushrooms without expert identification. If poisoning is suspected, contact a poison control center immediately and bring a sample of the mushroom for identification.

In summary, mushroom poisoning manifests through a spectrum of symptoms, from immediate nausea to life-threatening organ failure. Awareness of these signs, coupled with swift action, can prevent severe outcomes. Always exercise caution when foraging, and when in doubt, leave it out. Your life is worth more than a risky meal.

Mushroom Cultivation Without a Water Heater: Is It Possible?

You may want to see also

Common poisonous species: Amanita, Galerina, and Cortinarius are among the most dangerous poisonous mushrooms

Mushrooms, often celebrated for their culinary and medicinal value, harbor a darker side. Among the thousands of species, a select few pose grave dangers, with Amanita, Galerina, and Cortinarius standing out as the most notorious. These genera contain species responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings worldwide, their toxins insidious and often irreversible. Understanding their characteristics is not just academic—it’s a matter of survival for foragers and enthusiasts alike.

Take Amanita, for instance, a genus that includes the infamous *Amanita phalloides* (Death Cap) and *Amanita virosa* (Destroying Angel). These mushrooms produce amatoxins, cyclic octapeptides that cause severe liver and kidney damage. Symptoms may not appear for 6–24 hours after ingestion, lulling victims into a false sense of security. A single Death Cap contains enough toxin to kill an adult, and children are particularly vulnerable due to their lower body mass. The lesson here is clear: avoid any Amanita species unless you are an expert, and even then, exercise extreme caution.

Galerina mushrooms, often mistaken for harmless brown mushrooms like *Psathyrella* or *Pholiota*, are equally treacherous. They contain the same amatoxins as Amanita, making them just as deadly. What’s worse, Galerinas frequently grow on wood, mimicking edible species like the Oyster mushroom. Foragers should heed this warning: always scrutinize the substrate and never assume a mushroom is safe based on appearance alone. A magnifying glass and a field guide are indispensable tools in this context.

Cortinarius, with over 2,000 species, is a more complex case. While many are inedible or mildly toxic, a handful contain orellanine, a toxin that causes acute tubular necrosis, leading to kidney failure. Symptoms may take 2–3 days to appear, making diagnosis difficult. Unlike amatoxins, orellanine poisoning is treatable if caught early, but the window is narrow. The takeaway? Avoid all Cortinarius species unless positively identified as safe, and seek medical attention immediately if ingestion is suspected.

Practical tips can mitigate risk. First, never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. Second, cross-reference findings with multiple reliable sources, as misidentification is the leading cause of poisoning. Third, educate yourself on the specific dangers of Amanita, Galerina, and Cortinarius, as their toxins and symptoms differ. Finally, if in doubt, throw it out—no meal is worth the risk. By treating these species with the respect they demand, foragers can enjoy the bounty of the fungal kingdom without falling victim to its deadliest members.

Where to Buy Mushrooms in Ann Arbor: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$7.62 $14.95

Safe foraging practices: Proper identification, expert guidance, and avoiding unknown species prevent accidental poisoning

Mushrooms, with their diverse forms and habitats, can be both a forager’s delight and a hidden danger. While many species are safe and nutritious, others can cause severe illness or even death. The key to safe foraging lies in three critical practices: proper identification, seeking expert guidance, and avoiding unknown species. These steps are not just precautions—they are essential habits that can prevent accidental poisoning and ensure a rewarding foraging experience.

Proper identification is the cornerstone of safe mushroom foraging. Relying solely on color, shape, or habitat is risky, as many toxic species closely resemble edible ones. For instance, the deadly Amanita phalloides (Death Cap) can be mistaken for the edible Paddy Straw mushroom. To identify accurately, use a field guide with detailed descriptions and photographs, and pay attention to specific features like gill attachment, spore color, and the presence of a volva (a cup-like structure at the base). Digital tools like mushroom identification apps can assist, but they should complement, not replace, traditional methods. Always cross-reference findings with multiple reliable sources before consuming any mushroom.

Expert guidance is invaluable for both novice and experienced foragers. Joining a local mycological society or attending foraging workshops can provide hands-on learning and access to knowledgeable mentors. Experts can teach subtle distinctions between species, such as the difference between the edible Chanterelle and the toxic False Chanterelle, which has a forked cap and acrid taste. For those unable to attend in-person events, online forums moderated by mycologists offer a platform to share photos and receive feedback. Remember, even experts occasionally make mistakes, so always double-check identifications and avoid consuming mushrooms unless you are 100% certain.

Avoiding unknown species is a simple yet effective rule that can save lives. The temptation to experiment with unfamiliar mushrooms is high, especially when they appear similar to known edible varieties. However, many toxic species, like the Galerina marginata (Deadly Galerina), are deceptively ordinary in appearance. If you encounter a mushroom you cannot identify with absolute certainty, leave it undisturbed. This practice not only protects you but also preserves the ecosystem, as mushrooms play vital roles in nutrient cycling and soil health. For families with children or pets, educate them about the dangers of consuming wild mushrooms and supervise outdoor activities in mushroom-rich areas.

Incorporating these practices into your foraging routine transforms a potentially hazardous activity into a safe and enriching hobby. Proper identification, expert guidance, and avoiding unknown species are not just guidelines—they are safeguards that ensure the beauty and bounty of the fungal world can be enjoyed without risk. By respecting the complexity of mushrooms and approaching foraging with caution and knowledge, you can explore this fascinating realm with confidence and peace of mind.

Deep-Fried Mushrooms: Are They Safe for Your Dog to Eat?

You may want to see also

Cooking and preparation: Some toxic mushrooms require specific preparation methods to neutralize toxins before consumption

Certain mushrooms, like the *Lactarius torminosus* or "Woolly Milkcap," contain toxins that can be rendered harmless through proper cooking techniques. This process, known as detoxification, relies on heat to break down harmful compounds such as sesquiterpene lactones. Boiling these mushrooms for at least 15 minutes in water, followed by discarding the liquid, can significantly reduce their toxicity. However, this method is not universal; some toxins, like amatoxins found in the *Amanita* genus, remain stable even after prolonged cooking, making such mushrooms inherently dangerous regardless of preparation.

In contrast, the *Coprinus comatus*, or Shaggy Mane mushroom, contains coprine, a toxin that causes discomfort when consumed with alcohol. While this toxin is not life-threatening, it underscores the importance of understanding specific mushroom-toxin interactions. Proper identification and preparation, such as thorough cooking to denature coprine, can mitigate risks. This example highlights how knowledge of both the toxin and its susceptibility to heat can transform a potentially harmful mushroom into a safe culinary ingredient.

Foraging enthusiasts often encounter the *Morchella* genus, or morel mushrooms, which contain hydrazine toxins. These toxins can be neutralized by drying the mushrooms, a method that reduces moisture content and breaks down harmful compounds. Drying at temperatures above 60°C (140°F) for several hours is recommended. Alternatively, parboiling morels for 5 minutes before incorporating them into dishes ensures safety. These steps are crucial, as consuming raw or undercooked morels can lead to gastrointestinal distress, emphasizing the role of preparation in toxin management.

A cautionary tale comes from the *Gyromitra esculenta*, or False Morel, which contains gyromitrin, a toxin that converts to monomethylhydrazine in the body. This compound is a severe health risk, causing symptoms ranging from nausea to seizures. While some foragers advocate for prolonged boiling and soaking to reduce toxicity, experts warn that this method is unreliable. Even trace amounts of gyromitrin can accumulate over time, leading to long-term health issues. This mushroom exemplifies the limitations of cooking as a detoxification method, serving as a reminder that some toxins defy culinary intervention.

In practical terms, anyone preparing wild mushrooms should adhere to strict guidelines: always identify mushrooms with absolute certainty, consult reliable sources, and apply species-specific preparation methods. For instance, the *Boletus* genus, prized for its edible members, includes look-alikes like *Boletus huronensis*, which causes gastric upset unless properly cooked. Boiling for 10 minutes and discarding the water is a safe practice. Ultimately, while cooking can neutralize certain toxins, it is not a foolproof solution, and caution remains paramount in mushroom preparation.

Are Slimy Mushrooms Safe to Eat? A Fungal Food Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushrooms that are typically edible do not suddenly become poisonous on their own. However, they can absorb toxins from their environment, such as heavy metals or chemicals, making them unsafe to eat.

Mushrooms do not become poisonous simply by growing near toxic species. Each mushroom produces its own toxins independently, so proximity to poisonous mushrooms does not affect their edibility.

While aging can make mushrooms less palatable or cause them to decompose, it does not inherently make them poisonous. However, older mushrooms may be more susceptible to bacterial or fungal contamination, which can cause illness.

Cooking or drying cannot neutralize the toxins in poisonous mushrooms. Many mushroom toxins are heat-stable and remain harmful even after preparation. Always avoid consuming mushrooms unless you are certain they are safe.