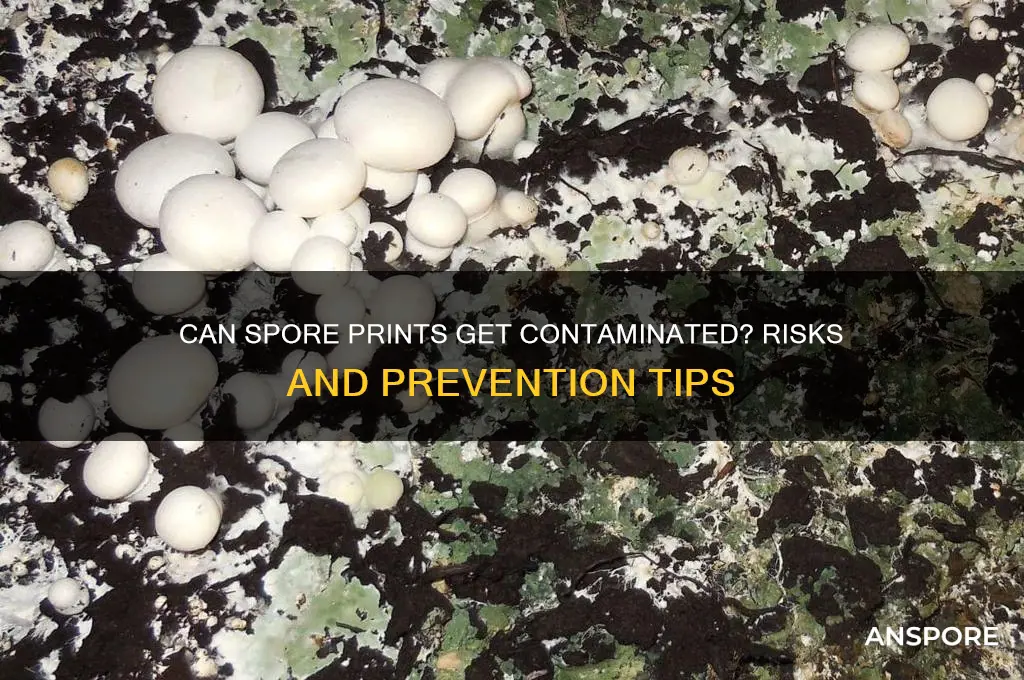

Spore prints, a common method used by mycologists and enthusiasts to identify mushroom species, involve placing the cap of a mushroom on a piece of paper or glass to capture the spores released from the gills or pores. While this technique is generally reliable, concerns about contamination can arise, potentially compromising the accuracy of the identification. Contamination can occur through various means, such as airborne particles, handling errors, or the presence of mold or bacteria on the mushroom itself. Understanding the factors that contribute to contamination and implementing proper techniques to minimize it is essential for obtaining clear and accurate spore prints.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can Spore Prints Get Contaminated | Yes, spore prints can get contaminated under certain conditions. |

| Common Contaminants | Bacteria, mold, yeast, and other fungal spores. |

| Sources of Contamination | Improper handling, unsterilized tools, exposure to air, dirty surfaces. |

| Prevention Methods | Sterilize tools, work in a clean environment, use gloves, avoid touching the print. |

| Storage Impact | Contamination risk increases with improper storage (e.g., high humidity, unsealed containers). |

| Detection Methods | Visual inspection, microscopic examination, or culturing the sample. |

| Effect on Identification | Contamination can lead to misidentification of the fungal species. |

| Longevity of Contaminated Prints | Contaminated prints may degrade faster and become unusable for identification. |

| Common Mistakes | Touching the spore print surface, using unclean glass, or exposing it to open air for too long. |

| Best Practices | Work quickly, minimize exposure, and store prints in airtight containers in a cool, dry place. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Common Contaminants in Spore Prints

Spore prints, a vital tool for mushroom identification, are not immune to contamination. Despite their microscopic nature, spores can be compromised by various external factors, leading to inaccurate results. Understanding these contaminants is crucial for mycologists and enthusiasts alike, as it ensures the integrity of their findings.

Environmental Factors: The Unseen Intruders

Imagine a scenario where a spore print is exposed to open air for an extended period. Dust particles, pollen, and even airborne mold spores can settle on the print, mimicking the appearance of the mushroom's spores. This contamination can lead to misidentification, especially in species with similar spore colors. For instance, a contaminated print from a *Coprinus* species might be mistaken for *Panaeolus*, both of which have dark spores. To mitigate this, it's essential to work in a clean environment, using a cover to protect the print during the collection process.

Bacterial Intrusion: A Microscopic Threat

Bacteria, though often beneficial in various ecosystems, can be detrimental to spore prints. Certain bacterial species can colonize the spore print, especially if the mushroom tissue was not properly cleaned before printing. This contamination may result in discolored or degraded prints, making identification challenging. A study by the Mycological Society of America suggests that bacterial contamination is more prevalent in spore prints from older mushrooms, as their tissues are more susceptible to bacterial invasion. To prevent this, ensure the mushroom cap is free from debris and use sterile tools for handling.

Chemical Interference: A Subtle Saboteur

Chemical contaminants can also compromise spore prints, often going unnoticed until it's too late. For example, residual chemicals from cleaning agents used on collection surfaces can alter spore color and structure. A common household disinfectant, when not thoroughly rinsed, can leave traces that affect the print's appearance. This is particularly problematic when trying to distinguish between species with subtle spore color variations, such as the *Amanita* genus. Always use clean, chemical-free surfaces and tools, and consider using a dedicated workspace for mycological activities.

Cross-Contamination: A Human Error

Human error is a significant contributor to spore print contamination. Reusing tools without proper sterilization or handling multiple mushroom species without changing gloves can lead to cross-contamination. This is especially critical when dealing with toxic or edible species, as misidentification can have severe consequences. A simple yet effective practice is to use disposable gloves and sterilize reusable tools with a 10% bleach solution, followed by thorough rinsing and drying. This ensures that each spore print is an accurate representation of the mushroom in question.

In the pursuit of accurate mushroom identification, being vigilant about these common contaminants is essential. By implementing simple yet effective practices, mycologists and enthusiasts can ensure the reliability of their spore prints, contributing to a more precise understanding of the fungal world.

Does Pasteurization Effectively Eliminate Bacterial Spores in Food Processing?

You may want to see also

Preventing Mold Growth on Spore Prints

Spore prints, essential for mushroom identification, are susceptible to mold contamination, which can compromise their integrity. Mold thrives in environments with moisture and organic matter, conditions often present during spore print collection and storage. Understanding the factors that contribute to mold growth is the first step in preventing it. Proper handling, storage, and environmental control are critical to preserving the purity of spore prints.

Steps to Prevent Mold Growth

Begin by ensuring the substrate (usually a glass or paper surface) is clean and dry before collecting spores. Sterilize the collection surface with isopropyl alcohol (70% concentration) to eliminate potential mold spores. After collecting the spore print, allow it to dry completely in a well-ventilated area, away from direct sunlight. Moisture is mold’s ally, so even slight dampness can trigger growth. Once dry, store the spore print in a sealed container with a desiccant packet to maintain low humidity levels. Silica gel packets, commonly found in packaging, are effective and reusable after drying in an oven at 250°F (121°C) for 2 hours.

Cautions to Consider

Avoid storing spore prints in areas prone to temperature fluctuations, such as near windows or heaters, as this can create condensation. While some collectors use parchment paper or aluminum foil for spore prints, these materials can trap moisture if not handled properly. If using paper, ensure it is acid-free and stored flat to prevent creases that might retain moisture. Additionally, refrain from touching the spore print with bare hands; use gloves or clean tweezers to minimize contamination from skin oils or bacteria.

Comparative Analysis of Storage Methods

Glass slides are superior to paper for long-term storage due to their non-porous nature, which resists moisture absorption. However, paper is more flexible and easier to label. For archival purposes, consider laminating paper spore prints or storing them between glass slides. Vacuum-sealed bags offer another layer of protection but require careful handling to avoid damaging the print. Compare these methods based on your needs: glass for durability, paper for convenience, and vacuum sealing for maximum protection.

Unveiling the Truth: Can Fungi Form Spores and How?

You may want to see also

Impact of Bacteria on Spore Prints

Bacterial contamination in spore prints can significantly alter their appearance and reliability for identification. When bacteria colonize the spore deposit, they often introduce discoloration, ranging from subtle hues of yellow or green to more pronounced brown or black patches. For instance, *Bacillus* species are known to produce pigments that can mimic or obscure the natural color of mushroom spores, leading to misidentification. This is particularly problematic for mycologists relying on spore print color as a diagnostic trait. To mitigate this, always inspect the substrate for signs of bacterial growth before collecting spores and consider sterilizing the collection surface with a 70% ethanol solution.

The impact of bacteria on spore prints extends beyond visual changes; it can also affect spore viability and density. Bacterial enzymes, such as proteases and lipases, may degrade the spore walls or surrounding tissues, reducing the number of intact spores available for analysis. A study published in *Mycologia* found that bacterial contamination decreased spore viability by up to 40% in samples stored for more than 48 hours. For accurate results, collect spore prints promptly and store them in a desiccated environment at room temperature. If contamination is suspected, use a sterile scalpel to excise the affected area before proceeding with identification.

From a practical standpoint, preventing bacterial contamination requires meticulous technique. Start by sterilizing all tools, including blades and glass surfaces, with a 10% bleach solution followed by ethanol. When cutting the mushroom cap, avoid touching the gills with your hands, as skin flora can introduce bacteria. For long-term storage, place the spore print in a sealed container with a silica gel packet to maintain dryness. If contamination occurs despite precautions, consider using a bacterial stain like Gram’s stain to identify the culprit and assess its impact on the sample.

Comparatively, bacterial contamination in spore prints is more common in humid environments or when using organic substrates like cardboard. In contrast, glass or aluminum foil provides a less hospitable surface for bacterial growth. A comparative study in *Fungal Biology* revealed that spore prints on aluminum foil retained 95% accuracy in color and density over two weeks, whereas those on cardboard showed visible bacterial interference within 72 hours. For field collections, prioritize non-porous materials and avoid collecting in damp conditions to minimize bacterial risks.

Finally, while bacterial contamination is a challenge, it also highlights the importance of cross-referencing identification methods. Relying solely on spore prints can lead to errors, especially in contaminated samples. Incorporate additional techniques, such as microscopic examination of spore morphology or DNA sequencing, to confirm findings. For example, a contaminated spore print from an *Amanita* species might still yield identifiable spores under 1000x magnification, even if the color is altered. By combining approaches, mycologists can ensure accurate identification despite bacterial interference.

Can Mould Spores Be Deadly? Uncovering the Hidden Risks

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$24.99 $39.95

Environmental Factors Causing Contamination

Spore prints, a vital tool in mycology for identifying mushroom species, are not immune to contamination. Environmental factors play a significant role in compromising their integrity. One primary culprit is humidity. High moisture levels can encourage the growth of unwanted bacteria, molds, or yeasts on the spore print surface. For instance, a spore print left uncovered in a humid environment (above 70% relative humidity) for more than 24 hours is at risk of contamination. To mitigate this, store spore prints in a dry, controlled environment, ideally with silica gel packets to absorb excess moisture.

Another environmental factor is airborne particles. Dust, pollen, or other organic matter in the air can settle on the spore print, obscuring or mixing with the spores. This is particularly problematic in outdoor settings or poorly ventilated spaces. Using a clean, enclosed container during the spore print process can reduce this risk. For example, placing the mushroom cap on a piece of glass or aluminum foil inside a covered container minimizes exposure to airborne contaminants.

Temperature fluctuations also contribute to contamination. Spores are resilient, but extreme temperatures can weaken their structure, making them susceptible to invasive microorganisms. Prolonged exposure to temperatures above 85°F (29°C) or below 40°F (4°C) can stress the spores, increasing the likelihood of contamination. Store spore prints in a temperature-stable environment, such as a cool, dark room or a refrigerator set between 40°F and 50°F (4°C and 10°C).

Lastly, surface cleanliness is often overlooked but critical. The material used to capture the spore print must be free of contaminants. For example, using unsterilized glass or paper can introduce bacteria or fungi that compete with or overwhelm the target spores. Always sterilize surfaces with isopropyl alcohol (70% concentration) before use. Additionally, ensure the mushroom itself is free of dirt or debris by gently brushing its gills or pores before making the spore print.

By addressing these environmental factors—humidity, airborne particles, temperature, and surface cleanliness—you can significantly reduce the risk of contamination in spore prints. These precautions not only preserve the accuracy of identification but also ensure the longevity of your mycological samples.

Can Your Computer Run Spore? System Requirements Explained

You may want to see also

Sterilization Techniques for Clean Spore Prints

Spore prints, essential for mushroom identification and cultivation, are susceptible to contamination from bacteria, mold, or foreign spores. Ensuring their purity is critical for accurate analysis and successful cultivation. Sterilization techniques play a pivotal role in achieving clean spore prints, safeguarding their integrity from collection to storage.

Surface Sterilization: The First Line of Defense

Before extracting spores, sterilize the mushroom’s cap surface to prevent contaminants from transferring to the print. Wipe the cap with a 70% isopropyl alcohol solution, ensuring even coverage without saturating the tissue. Allow it to air-dry for 5–10 minutes to evaporate residual alcohol. Alternatively, flame sterilization using a lighter or torch can be effective for woody or thick-skinned species, but caution is required to avoid damaging the mushroom’s structure. This step is particularly crucial for wild-harvested specimens, which often carry environmental debris.

Equipment Sterilization: Tools Matter

Contamination often arises from unsterilized tools. Glass or metal surfaces, such as blades or spore print slides, should be sterilized using a 10% bleach solution (1 part bleach to 9 parts water) for 10 minutes, followed by thorough rinsing with sterile water. Autoclaving at 121°C (250°F) for 15 minutes is ideal for heat-resistant materials, ensuring complete eradication of microorganisms. For single-use items, disposable scalpel blades and sterile gloves minimize cross-contamination risks. Always handle sterilized equipment with clean hands or within a laminar flow hood to maintain aseptic conditions.

Environmental Control: The Invisible Threat

Airborne contaminants pose a significant risk during spore print collection. Work in a clean, dust-free environment, preferably with a HEPA filter or laminar flow hood. If such equipment is unavailable, cover the workspace with a sterile drape and limit air movement by closing windows and doors. Time is critical; complete the process swiftly to reduce exposure to ambient particles. For added protection, use a sterile petri dish or glass container to cover the spore print during collection, creating a makeshift barrier against airborne contaminants.

Storage Sterilization: Preserving Purity Long-Term

Once collected, spore prints must be stored in sterile conditions to prevent degradation or contamination. Use glass vials with airtight seals, sterilized by autoclaving or dry heat at 160°C (320°F) for 2 hours. Store prints in a desiccant-lined container to maintain dryness, as moisture fosters bacterial growth. Label vials with collection date and species, and store in a cool, dark place. For extended preservation, consider vacuum-sealing or freezing at -20°C (-4°F), though this may affect spore viability in some species. Regularly inspect stored prints for signs of mold or discoloration, discarding any compromised samples.

Comparative Efficacy: Choosing the Right Method

While alcohol and flame sterilization are effective for surface decontamination, they may not suffice for all scenarios. Autoclaving offers the highest sterility assurance but is impractical for field collections. Bleach solutions provide a balance of accessibility and efficacy, though residual chemicals must be thoroughly removed. For hobbyists, a combination of alcohol wipes and sterile gloves often yields satisfactory results. Advanced cultivators may invest in a pressure cooker for autoclaving or a laminar flow hood for controlled environments. The choice depends on resources, scale, and desired sterility level.

By implementing these sterilization techniques, spore prints can remain uncontaminated, ensuring reliable identification and cultivation outcomes. Attention to detail at every step—from collection to storage—is key to preserving their purity.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: A Guide to Growing Spores Successfully

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, spore prints can get contaminated if exposed to bacteria, mold, or other foreign spores during the collection or storage process.

To prevent contamination, sterilize your workspace, use clean tools, and ensure the mushroom cap is free of dirt or debris before placing it on the surface.

Yes, contamination can introduce foreign spores or growths that interfere with the accuracy of the spore print, making identification difficult or unreliable.

A contaminated spore print is not ideal for cultivation, as it may introduce unwanted organisms that compete with or harm the desired mushroom species.