Fungi are a diverse group of organisms known for their unique reproductive strategies, and one of their most remarkable abilities is the formation of spores. These microscopic structures serve as a means of dispersal and survival, allowing fungi to thrive in various environments. Spores are produced through both sexual and asexual processes, depending on the fungal species and environmental conditions. They are highly resilient, capable of withstanding harsh conditions such as extreme temperatures, drought, and even radiation. Once released, spores can travel through air, water, or soil, enabling fungi to colonize new habitats and ensure their continued existence. This adaptability makes spore formation a crucial aspect of fungal biology and ecology.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Can Fungi Form Spores? | Yes |

| Types of Spores | Asexual (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores) and Sexual (e.g., zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores) |

| Function of Spores | Reproduction, dispersal, and survival in harsh conditions |

| Formation Process | Asexual spores form via mitosis; sexual spores form via meiosis |

| Dispersal Methods | Wind, water, animals, or mechanical means |

| Dormancy | Spores can remain dormant for extended periods until favorable conditions arise |

| Resistance | Highly resistant to extreme temperatures, desiccation, and chemicals |

| Examples of Spore-Forming Fungi | Aspergillus, Penicillium, Mucor, Fusarium, and many others |

| Ecological Role | Key role in nutrient cycling, decomposition, and ecosystem dynamics |

| Medical Significance | Some fungal spores can cause allergies, infections (e.g., aspergillosis), or act as pathogens |

| Industrial Applications | Used in food production (e.g., cheese, bread), biotechnology, and medicine (e.g., antibiotics like penicillin) |

Explore related products

$22.04 $29.99

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Process: How fungi develop and release spores under specific environmental conditions

- Types of Spores: Classification of fungal spores (e.g., conidia, zygospores, ascospores)

- Environmental Triggers: Factors like light, temperature, and nutrients that induce spore formation

- Survival Mechanisms: How spores help fungi survive harsh conditions (e.g., drought, cold)

- Dispersal Methods: Ways spores spread, including wind, water, and animal vectors

Sporulation Process: How fungi develop and release spores under specific environmental conditions

Fungi are masters of survival, and their ability to form spores is a key strategy in their lifecycle. Sporulation, the process by which fungi develop and release spores, is a complex and highly regulated mechanism triggered by specific environmental conditions. This process ensures the fungus’s survival during unfavorable conditions, such as nutrient scarcity, extreme temperatures, or desiccation. Spores are lightweight, resilient, and capable of remaining dormant for extended periods, allowing fungi to disperse and colonize new habitats when conditions improve.

The sporulation process begins with the detection of environmental cues, such as changes in nutrient availability, pH, or light exposure. For example, *Aspergillus niger*, a common mold, initiates sporulation when carbon sources are depleted. In response, the fungus undergoes cellular differentiation, forming specialized structures like sporangia or asci, depending on the fungal species. In *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker’s yeast), sporulation is triggered by nitrogen starvation, leading to the formation of four haploid spores within an ascus. This differentiation involves intricate genetic and biochemical pathways, including the activation of sporulation-specific genes like *SPO11* and *SPO13*.

Once mature, spores are released through mechanisms tailored to the fungus’s ecology. For instance, puffballs (*Lycoperdon* spp.) rely on wind dispersal, releasing clouds of spores when disturbed. In contrast, rust fungi (*Puccinia* spp.) use explosive mechanisms, launching spores with sufficient force to travel short distances. Aquatic fungi, like *Blastocladiella*, release motile zoospores that swim toward favorable environments. The timing and method of spore release are critical for successful dispersal and colonization, ensuring the fungus’s survival across generations.

Practical considerations for studying or managing sporulation include controlling environmental factors to inhibit unwanted fungal growth. For example, maintaining low humidity (below 60%) and temperatures between 20–25°C can suppress mold sporulation in indoor environments. In industrial settings, such as food production, monitoring nutrient levels and pH can prevent fungal contamination. For researchers, inducing sporulation in laboratory conditions often requires precise manipulation of media composition, such as using sporulation medium (e.g., 1% potassium acetate for *S. cerevisiae*). Understanding these conditions not only aids in fungal control but also harnesses their potential in biotechnology, such as spore-based biopesticides or enzyme production.

In conclusion, the sporulation process is a remarkable adaptation that highlights fungi’s resilience and versatility. By responding to specific environmental cues, fungi ensure their survival through the production and dispersal of spores. Whether in natural ecosystems or controlled environments, understanding this process offers practical insights for managing fungal growth and leveraging their capabilities in various applications. From the explosive release of rust spores to the dormancy of yeast asci, sporulation is a testament to the ingenuity of fungal life cycles.

How Spores Evolve for Efficient Wind Dispersal: Nature's Strategy

You may want to see also

Types of Spores: Classification of fungal spores (e.g., conidia, zygospores, ascospores)

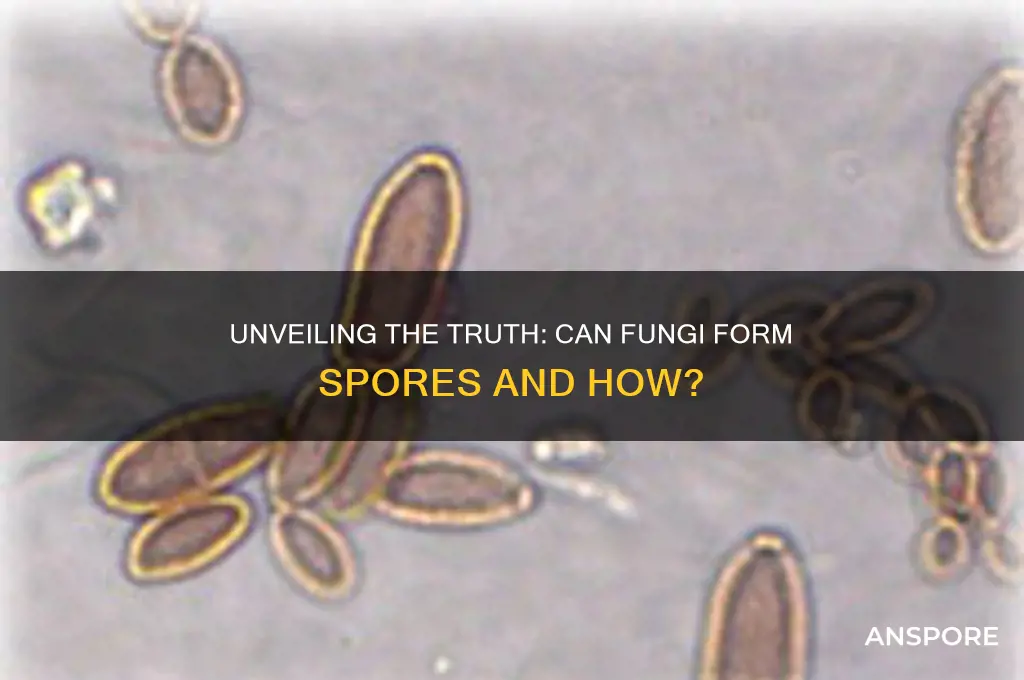

Fungi are masters of survival, and their ability to form spores is a key strategy. These microscopic structures are not just dormant cells; they are highly specialized for dispersal, survival in harsh conditions, and rapid germination when conditions improve. Understanding the different types of fungal spores—such as conidia, zygospores, and ascospores—reveals the diversity of fungal reproductive strategies and their ecological roles.

Conidia: The Asexual Workhorses

Conidia are asexual spores produced at the ends of specialized hyphae called conidiophores. They are among the most common fungal spores and are responsible for the rapid spread of many fungi, including those causing plant diseases like powdery mildew and black mold in homes. Conidia are typically single-celled, lightweight, and easily dispersed by wind or water. For example, *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* fungi produce conidia in vast quantities, which can become airborne and colonize new substrates within hours. To control conidia-producing fungi in indoor environments, maintain humidity below 60% and promptly address water leaks, as these spores thrive in damp conditions.

Zygospores: The Survivors of Fusion

Zygospores are formed through the sexual fusion of two compatible hyphae in fungi of the phylum Zygomycota. These thick-walled spores are highly resistant to environmental stresses, such as desiccation and extreme temperatures, making them ideal for long-term survival. For instance, the black bread mold *Rhizopus* produces zygospores that can remain dormant in soil for years before germinating when conditions are favorable. While zygospores are less common in indoor environments, their resilience underscores the importance of thorough cleaning and disinfection to prevent fungal recurrence.

Ascospores: The Products of Sexual Reproduction

Ascospores are sexual spores produced within sac-like structures called asci in Ascomycota, the largest fungal phylum. These spores are often ejected forcefully from the ascus, allowing for efficient dispersal. *Fusarium* and *Colletotrichum* are examples of ascomycetes that produce ascospores, which play a significant role in plant diseases. Ascospores are also found in indoor environments, particularly in water-damaged buildings, where they can contribute to respiratory issues. To minimize their impact, use HEPA filters to capture airborne spores and regularly inspect HVAC systems for mold growth.

Comparative Analysis and Practical Takeaways

While conidia, zygospores, and ascospores all serve as dispersal and survival mechanisms, their formation, structure, and ecological roles differ markedly. Conidia are the most prevalent and rapidly produced, making them key players in fungal spread. Zygospores, though less common, are unparalleled in their durability. Ascospores, meanwhile, highlight the importance of sexual reproduction in fungal diversity and adaptation. For homeowners and professionals, understanding these distinctions can inform targeted strategies for mold prevention and remediation. Regular monitoring, moisture control, and proper ventilation are essential to disrupt the life cycles of these spores and maintain healthy indoor environments.

Can Spore Syringes Contaminate During Storage Between Uses?

You may want to see also

Environmental Triggers: Factors like light, temperature, and nutrients that induce spore formation

Fungi, unlike animals, lack the luxury of mobility. To disperse and colonize new environments, they rely on spores, microscopic units of reproduction. But spore formation isn't a constant process. It's a strategic response, triggered by specific environmental cues. Light, temperature, and nutrient availability act as conductors, orchestrating the intricate dance of spore development.

Understanding these triggers is crucial for various fields. Farmers can manipulate conditions to control fungal pathogens, while mycologists can optimize spore production for research or biotechnological applications.

The Light Switch: Illuminating Spore Development

Light, particularly its wavelength and intensity, plays a pivotal role in spore formation. Many fungi exhibit phototropism, growing towards light sources. This response is often linked to spore production. Blue light, in the range of 400-500 nanometers, is particularly effective in inducing sporulation in species like *Aspergillus nidulans*. Interestingly, some fungi, like *Neurospora crassa*, require complete darkness for spore formation, highlighting the diverse ways light influences this process.

Experimentally, exposing fungal cultures to specific light wavelengths and intensities for controlled periods can significantly impact spore yield. For instance, a study found that 12 hours of blue light exposure daily increased spore production in *Penicillium chrysogenum* by 40%.

Temperature: The Thermostat of Sporulation

Temperature acts as a master regulator, influencing the timing and extent of spore formation. Each fungal species has an optimal temperature range for sporulation. Deviations from this range can either inhibit or accelerate the process. For example, *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, commonly known as baker's yeast, sporulates most efficiently at temperatures between 25-30°C. Lower temperatures can delay sporulation, while higher temperatures may prevent it altogether.

Nutrient Availability: Fueling the Spore Factory

Nutrients are the building blocks of spores. When nutrients become scarce, fungi often respond by entering a reproductive phase, producing spores to ensure survival. This is particularly evident in filamentous fungi, which form specialized structures called conidiophores to bear spores. Nitrogen limitation is a common trigger for sporulation in many species. When nitrogen levels drop below a certain threshold, typically around 10 mM ammonium ions, fungi like *Aspergillus niger* initiate spore production.

Orchestrating the Symphony: A Delicate Balance

These environmental triggers don't act in isolation. They interact in a complex symphony, fine-tuning spore formation. For instance, the combined effect of light and nutrient limitation can significantly enhance sporulation in some species. Understanding these intricate relationships allows us to manipulate fungal behavior, whether it's controlling unwanted fungal growth or optimizing spore production for beneficial applications. By deciphering the language of environmental cues, we gain a powerful tool to harness the potential of these remarkable organisms.

Exploring the Unique Characteristics of Agaricus Mushroom Spores

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Survival Mechanisms: How spores help fungi survive harsh conditions (e.g., drought, cold)

Fungi, unlike animals that flee or plants that wither, face environmental extremes head-on through the production of spores. These microscopic, often single-celled structures are not just reproductive tools but survival capsules engineered to endure conditions that would destroy the parent organism. When faced with drought, cold, or nutrient scarcity, fungi enter a dormant state by forming spores, which can remain viable for years, even centuries, until conditions improve. This ability to suspend life is a testament to the evolutionary ingenuity of fungi, allowing them to colonize nearly every habitat on Earth.

Consider the desert-dwelling fungus *Aspergillus* spp., which thrives in arid environments by producing spores resistant to desiccation. These spores have a thickened cell wall and reduced metabolic activity, enabling them to survive temperatures exceeding 50°C and humidity levels below 10%. Similarly, psychrophilic fungi like *Cryptococcus* spp. produce cold-resistant spores that remain dormant in freezing soils, only germinating when temperatures rise. Such adaptations highlight the spore’s role as a biological time capsule, preserving genetic material until the environment becomes hospitable again.

To understand the spore’s survival mechanism, imagine a seed bank for fungi. Spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind, water, or animals, allowing fungi to colonize new areas rapidly once conditions improve. For instance, after a forest fire, heat-resistant spores of *Neurospora* spp. germinate in the nutrient-rich ash, aiding ecosystem recovery. This dispersal strategy ensures that even if a local population is wiped out, spores can travel to more favorable locations, maintaining the species’ continuity.

Practical applications of spore survival mechanisms are vast. In agriculture, understanding spore dormancy can improve crop protection against fungal pathogens. For example, knowing that *Fusarium* spores can survive in soil for over a decade helps farmers implement long-term rotation strategies. In biotechnology, spores’ resistance to extreme conditions inspires the development of preservation techniques for vaccines and enzymes. By mimicking spore structures, scientists are creating stabilizers for heat-sensitive drugs, ensuring their efficacy in remote or resource-limited areas.

In conclusion, spores are not just a means of reproduction but a survival toolkit for fungi. Their ability to withstand drought, cold, and other stresses underscores their role as nature’s ultimate survivalists. By studying these mechanisms, we unlock insights into resilience, with applications ranging from agriculture to medicine. The next time you see mold reappearing after cleaning, remember: it’s not just persistence—it’s the power of spores at work.

Rain's Role in Spreading Fungal Spores: Myth or Reality?

You may want to see also

Dispersal Methods: Ways spores spread, including wind, water, and animal vectors

Fungi are masters of dispersal, employing a variety of strategies to spread their spores far and wide. Among the most common methods are wind, water, and animal vectors, each offering unique advantages for colonization and survival. Wind dispersal, for instance, is a passive yet highly effective technique. Spores, often lightweight and equipped with structures like wings or tails, are carried by air currents over vast distances. This method is particularly prevalent in species like *Puccinia* (rust fungi) and *Cladosporium*, which can travel hundreds of miles, ensuring genetic diversity and access to new habitats. However, wind dispersal is unpredictable, relying heavily on weather conditions, which can limit its efficiency in certain environments.

Water, on the other hand, provides a more directed means of dispersal, especially in aquatic or humid ecosystems. Fungi like *Phycomyces* and *Pilobolus* eject their spores with force, often using water as a medium. For example, *Pilobolus* can launch spores up to 2 meters away, aiming toward light sources, which often correlate with the presence of water. In aquatic environments, spores may float on water surfaces or be carried by currents, allowing fungi to colonize new substrates like decaying wood or plant matter. This method is particularly effective in rainforests and wetlands, where water is abundant and predictable. However, it is less useful in arid regions, where water is scarce.

Animal vectors introduce a more targeted and reliable dispersal mechanism. Fungi like *Cordyceps* and *Coprinus* produce spores that adhere to the bodies of insects, rodents, or other animals. For instance, *Cordyceps* spores attach to ants, which then carry them to new locations, often infecting other ants in the colony. Similarly, birds and mammals may inadvertently transport spores on their fur or feathers, spreading fungi across diverse habitats. This method ensures that spores reach specific environments, such as animal nests or burrows, where conditions may be favorable for fungal growth. However, reliance on animal vectors limits dispersal to areas frequented by these creatures, reducing reach in isolated or inhospitable regions.

Each dispersal method comes with trade-offs, and fungi often employ multiple strategies to maximize their chances of survival. For example, a fungus might produce both wind-dispersed and animal-carried spores, ensuring adaptability to different environments. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for managing fungal populations, whether in agriculture, forestry, or medicine. For instance, controlling wind-dispersed pathogens in crops may require windbreaks or fungicides, while managing animal-vectored fungi might involve pest control or habitat modification. By studying these dispersal methods, we can better predict and mitigate the spread of both beneficial and harmful fungi, fostering healthier ecosystems and more resilient industries.

Can Spores or Pollen Survive in Distilled Water? Exploring the Science

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all fungi can form spores. While most fungi reproduce via spores, some species, like certain yeasts, primarily reproduce asexually through budding or fission.

Fungi form spores through specialized structures like sporangia, asci, or basidia, depending on the species. Spores are produced via sexual or asexual reproduction and are released into the environment for dispersal.

Fungi form spores as a survival and dispersal mechanism. Spores are lightweight, durable, and can withstand harsh conditions, allowing fungi to spread to new environments and survive unfavorable conditions like drought or extreme temperatures.