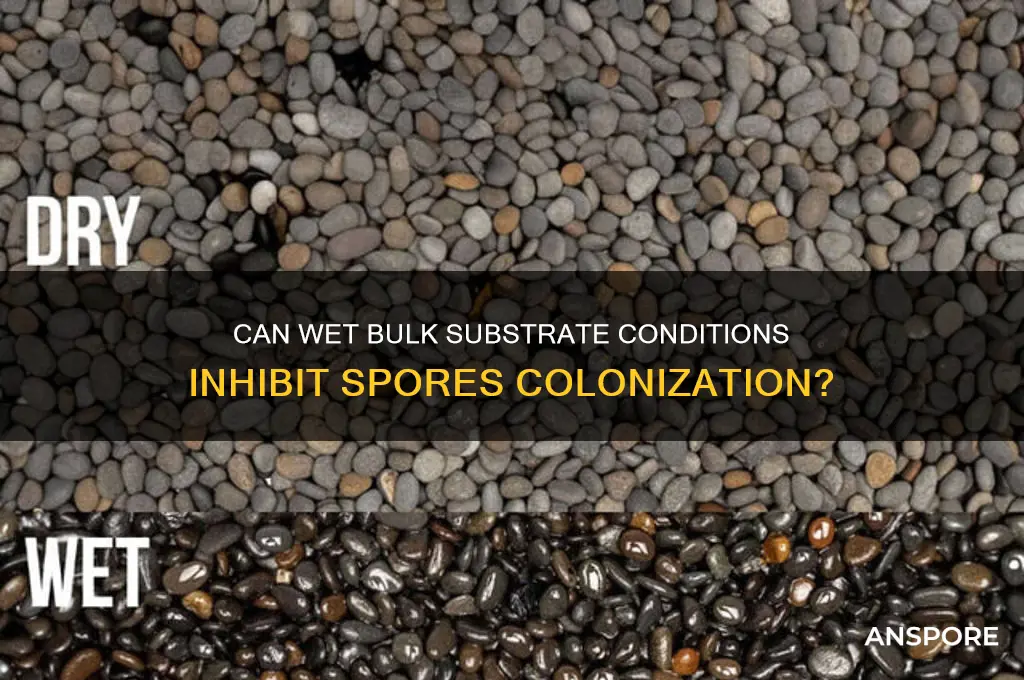

The Water Content (WC) of a substrate is a critical factor in the successful colonization of spores, particularly in mushroom cultivation. While a certain level of moisture is necessary to support mycelial growth, the question arises: can a substrate be too wet for spores to colonize? Excessive moisture can create an anaerobic environment, hindering oxygen exchange and potentially leading to contamination by competing microorganisms. Moreover, waterlogged substrates may cause spores to drown or fail to germinate due to insufficient oxygen availability. Therefore, understanding the optimal moisture balance is essential for creating a conducive environment that promotes spore germination and mycelial expansion, ultimately influencing the success of the cultivation process.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Optimal Moisture Range for Colonization | 50-60% moisture content in the substrate (WBS - Wheat Berry Spawn) |

| Excessive Moisture Effects | Inhibits oxygen availability, leading to anaerobic conditions |

| Risk of Contamination | High moisture increases the risk of bacterial and mold contamination |

| Water Activity (Aw) Threshold | Spores struggle to colonize when Aw > 0.95 (too wet) |

| Substrate Breakdown | Excess water causes substrate to break down, reducing nutrient availability |

| Temperature Sensitivity | Wet substrates can trap heat, affecting colonization efficiency |

| pH Changes | Overly wet conditions may alter substrate pH, hindering colonization |

| Remediation Strategy | Proper drainage, sterilization, and maintaining optimal moisture levels |

| Common Mistakes | Overwatering, lack of ventilation, and improper substrate preparation |

| Species Variability | Some mushroom species tolerate higher moisture better than others |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Optimal moisture levels for spore colonization in different substrates

- Effects of excessive water on mycelium growth and development

- How waterlogged conditions inhibit spore germination and colonization?

- Techniques to manage moisture content in WBS for successful colonization

- Role of substrate density and water retention in spore colonization

Optimal moisture levels for spore colonization in different substrates

Moisture is a critical factor in spore colonization, but the optimal level varies significantly depending on the substrate. For instance, wood-based substrates (WBS) like sawdust or wood chips require a delicate balance. Too much moisture can create anaerobic conditions, stifling spore growth, while too little can prevent spores from germinating. The ideal moisture content for WBS typically falls between 50-65% of the substrate’s dry weight. This range ensures sufficient water for spore hydration without promoting waterlogging or mold competition.

Consider the role of moisture in nutrient accessibility. Spores rely on water to dissolve and transport nutrients from the substrate into their cells. In WBS, a moisture content below 50% can render nutrients inaccessible, halting colonization. Conversely, above 65%, excess water fills air pockets, depriving spores of the oxygen they need to metabolize. For example, in a study on *Pleurotus ostreatus* (oyster mushroom), colonization rates peaked at 60% moisture, with significant declines at 70% due to waterlogged conditions.

Practical tips for achieving optimal moisture in WBS include pre-soaking the substrate and draining excess water before sterilization. A simple test: squeeze a handful of the substrate—it should release 1-2 drops of water, not drip continuously. For beginners, using a moisture meter can provide precise control, ensuring the substrate falls within the 50-65% range. Additionally, mixing WBS with materials like vermiculite can improve water retention and aeration, creating a more forgiving environment for spores.

Comparing WBS to other substrates highlights the importance of substrate-specific moisture management. For instance, straw-based substrates thrive at slightly lower moisture levels (45-55%) due to their higher air-to-water ratio. Meanwhile, grain substrates like rye or wheat berries require higher moisture (60-70%) during initial hydration but must be drained to 50-60% post-sterilization to avoid drowning the spores. Understanding these differences is key to tailoring moisture levels for successful colonization across substrates.

Finally, environmental factors like temperature and humidity interact with moisture to influence colonization. In warmer conditions (24-28°C), WBS may dry out faster, necessitating more frequent misting or a slightly higher initial moisture content. Conversely, in cooler environments (20-22°C), evaporation slows, and maintaining the lower end of the moisture range (50-55%) can prevent oversaturation. Monitoring these variables ensures spores receive the consistent moisture they need to thrive, regardless of the substrate or setting.

Breathing Fungal Spores: Uncovering Potential Health Risks and Concerns

You may want to see also

Effects of excessive water on mycelium growth and development

Excessive moisture in a substrate can significantly hinder mycelium growth, creating an environment more hostile than hospitable. Mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus, thrives in conditions that balance moisture and aeration. When a substrate, such as a grain spawn or bulk substrate, becomes waterlogged, oxygen availability plummets. This anaerobic environment stifles mycelial respiration, leading to slowed growth or even death. For instance, in a typical wheat berry spawn (WBS), a moisture content exceeding 70% can suffocate the mycelium, preventing it from colonizing effectively. The key takeaway? Maintain moisture levels between 50-60% to ensure optimal oxygen exchange and mycelial development.

Consider the analogy of a sponge: too dry, and it’s useless; too wet, and it becomes a breeding ground for stagnation. Mycelium behaves similarly. Excess water not only deprives it of oxygen but also dilutes essential nutrients, making them less accessible. In a WBS, for example, overhydration can leach out vital sugars and starches, leaving the mycelium starved despite being surrounded by substrate. This nutrient deficiency further compounds the stress caused by oxygen deprivation, creating a double-edged sword that halts colonization. To mitigate this, pre-soak grains for no more than 24 hours and drain thoroughly before inoculation, ensuring excess water is removed.

From a practical standpoint, monitoring hydration levels is crucial for successful colonization. A simple test involves squeezing a handful of the substrate: if water drips out, it’s too wet. For bulk substrates like coco coir or straw, aim for a "wrung-out sponge" consistency—moist but not dripping. For WBS, a moisture content of 55-60% is ideal, achievable by mixing 1 part water to 3 parts dry grains by weight. If overhydration occurs, spread the substrate thinly to allow evaporation, or mix in dry material to absorb excess moisture. Remember, mycelium is resilient but not invincible; corrective actions must be swift to salvage a compromised batch.

The consequences of excessive water extend beyond immediate growth inhibition. Prolonged exposure to high moisture levels can foster contamination by water-loving bacteria and molds, which outcompete mycelium for resources. This is particularly problematic in WBS, where the dense grain structure traps moisture, creating microenvironments conducive to contaminants. To prevent this, sterilize substrates thoroughly and ensure proper airflow during incubation. Additionally, using a hydrometer or moisture meter can provide precise readings, allowing for adjustments before inoculation. By treating water as a resource to manage, not a passive component, cultivators can safeguard mycelium from the pitfalls of overhydration.

Predicting Spore's Defeat: Analyzing Potential Round Losses in the Match

You may want to see also

How waterlogged conditions inhibit spore germination and colonization

Waterlogged conditions can significantly hinder spore germination and colonization, primarily by disrupting the delicate balance of oxygen and moisture required for fungal growth. Spores, the reproductive units of fungi, rely on a precise interplay of environmental factors to initiate germination. Excess water in the substrate, such as in a waterlogged WBS (wheat bran spawn), creates an anaerobic environment that deprives spores of the oxygen necessary for metabolic processes. Without adequate oxygen, spores struggle to break dormancy, and even if they do, the lack of aerobic respiration stifles energy production, halting further development.

Consider the substrate’s water activity (aw), a measure of free water available for microbial use. Most fungi thrive at an aw of 0.90–0.99, but waterlogged conditions can push this value above 0.99, effectively drowning spores. For example, in WBS, a moisture content exceeding 70% often leads to waterlogging. At this level, water fills the substrate’s air pockets, leaving no room for gas exchange. Spores submerged in such conditions fail to absorb sufficient oxygen, and the excess water dilutes nutrients, further inhibiting growth. Practical tip: Aim for a moisture content of 60–65% in WBS to maintain optimal aw and prevent waterlogging.

Another critical factor is temperature, which interacts with moisture to influence spore viability. Waterlogged substrates often retain heat poorly, creating temperature fluctuations that stress spores. For instance, a waterlogged WBS may cool unevenly, dropping below the ideal germination temperature range of 22–28°C (72–82°F). This thermal instability, combined with oxygen deprivation, creates a hostile environment where spores either fail to germinate or produce weak, stunted mycelium. Caution: Avoid using cold or unsterilized water when preparing WBS, as it increases the risk of waterlogging and contamination.

Comparatively, well-drained substrates allow spores to access both moisture and oxygen, fostering robust colonization. In contrast, waterlogged conditions force spores into a survival mode, where energy is diverted to repairing cellular damage rather than growth. Over time, this stress weakens the fungal population, making it susceptible to contaminants like bacteria, which thrive in anaerobic, water-rich environments. Takeaway: Proper substrate preparation, including adequate drainage and moisture control, is essential to ensure spores can germinate and colonize successfully.

Finally, the duration of waterlogging plays a pivotal role in spore survival. Short-term exposure may only delay germination, but prolonged waterlogging can lead to irreversible damage. For example, spores submerged in waterlogged WBS for more than 48 hours often exhibit reduced viability, with germination rates dropping by 50% or more. To mitigate this, monitor substrate moisture levels regularly and intervene at the first sign of waterlogging by aerating the substrate or reducing ambient humidity. Practical tip: Use a moisture meter to measure WBS moisture content and adjust as needed to maintain optimal conditions for spore colonization.

Can Pseudomonas Form Spores? Unraveling the Bacterial Survival Mystery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Techniques to manage moisture content in WBS for successful colonization

Excess moisture in WBS (wheat bran spawn) can create an anaerobic environment, hindering spore germination and mycelial growth. This occurs when water content exceeds the substrate's water-holding capacity, typically around 60-70% for WBS. Above this threshold, oxygen becomes scarce, promoting bacterial competition and drowning delicate fungal hyphae.

Balancing Act: Techniques for Optimal Moisture

The key lies in precise hydration control. Start by targeting a moisture content of 55-65% for WBS. Measure dry substrate weight, then add distilled water at a ratio of 2-2.5 parts water to 7-8 parts substrate (by weight). Mix thoroughly, ensuring even distribution. Verify moisture level by squeezing a handful: it should form a ball without releasing excess water. If too wet, spread the mixture thinly to air-dry, stirring periodically.

Active Management During Colonization

Once inoculated, monitor humidity within the incubation environment. Maintain relative humidity at 60-70% using a humidifier or by misting the container walls (not the substrate). For bulk substrates, incorporate 1-2% gypsum (calcium sulfate) by weight to improve water retention and prevent pooling. Periodically ventilate the incubation chamber to replenish oxygen, especially if condensation forms on container surfaces.

Troubleshooting Over-Saturation

If colonization stalls due to excess moisture, introduce absorbent amendments. Mix in 5-10% vermiculite or perlite (by volume) to wick away excess water without depriving the mycelium of necessary hydration. Alternatively, create a drainage layer at the bottom of the container using 1-2 cm of coarse sand or gravel. For severely waterlogged batches, carefully tilt the container to drain excess liquid, then re-seal and resume incubation.

Preventive Measures for Consistent Success

Pre-sterilize substrates using a pressure cooker at 15 psi for 60-90 minutes to eliminate competing organisms that thrive in wet conditions. Store dry WBS in airtight containers with silica gel packets to maintain <50% humidity. When rehydrating, use a spray bottle to apply water incrementally, testing moisture at each stage. Finally, calibrate your technique by documenting moisture levels, colonization rates, and environmental conditions for each batch to refine your process over time.

Dry Rot Spores: Uncovering Potential Health Risks and Concerns

You may want to see also

Role of substrate density and water retention in spore colonization

Substrate density and water retention are critical factors in determining whether spores can successfully colonize a given medium. A substrate that is too dense can restrict oxygen availability, which is essential for spore germination and mycelial growth. For instance, in wood-based substrates (WBS), a density exceeding 0.6 g/cm³ often impedes colonization due to poor gas exchange. Conversely, a substrate that retains excessive moisture can create anaerobic conditions, drowning spores and preventing colonization. Optimal WBS typically has a density between 0.4 and 0.5 g/cm³, balancing structural integrity with aeration.

Water retention in substrates is equally pivotal, as it directly influences spore viability and mycelial expansion. Spores require a thin film of water to activate metabolic processes, but excessive moisture can lead to waterlogging. For example, WBS with a water retention capacity above 70% often becomes too saturated, inhibiting oxygen diffusion and fostering bacterial competition. Practical guidelines suggest maintaining substrate moisture at 60-65% of its water-holding capacity to ensure spores have access to both water and oxygen. This range is particularly critical during the initial colonization phase, where spores are most vulnerable to environmental stressors.

To optimize spore colonization, consider the interplay between substrate density and water retention. A dense substrate with high water retention is a double-edged sword, as it exacerbates both oxygen deprivation and waterlogging risks. For WBS, incorporating coarse particles (e.g., 5-10% wood chips >5 mm) can improve aeration without significantly reducing water-holding capacity. Additionally, pre-soaking substrates to 65% moisture content and allowing them to drain for 24 hours ensures uniform hydration without oversaturation. These steps are particularly effective for mushroom cultivation, where precise control of these variables can increase colonization rates by up to 30%.

Comparatively, substrates with lower density and moderate water retention, such as those amended with 20-30% straw or coconut coir, often yield better colonization outcomes. Coconut coir, for instance, has a water retention capacity of 60-70% and a loose structure that promotes aeration. When mixed with WBS at a 1:3 ratio, it creates an ideal environment for spores, balancing moisture availability and gas exchange. This approach is especially beneficial for beginner cultivators, as it reduces the risk of common pitfalls like overwatering or compaction.

In conclusion, mastering the role of substrate density and water retention is essential for successful spore colonization. By maintaining substrate density below 0.5 g/cm³ and water retention at 60-65%, cultivators can create an environment conducive to spore germination and mycelial growth. Practical strategies, such as incorporating coarse particles and using moisture-regulating amendments like coconut coir, further enhance colonization efficiency. Whether for mushroom cultivation or other mycological applications, attention to these details ensures optimal conditions for spore development.

Are Liberty Caps Spore Prints Brown? Exploring Mushroom Identification

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, WBS that is too wet can create an anaerobic environment, which inhibits spore colonization by promoting bacterial growth and preventing proper oxygenation.

The ideal moisture level for WBS is around 60-70% field capacity, ensuring it is damp but not soggy, allowing spores to thrive without becoming waterlogged.

If the WBS feels overly soggy, water pools on the surface, or it emits a foul odor, it is likely too wet and unsuitable for spore colonization.

Yes, you can salvage overly wet WBS by spreading it out to dry, stirring it regularly, and reintroducing moisture gradually until it reaches the optimal dampness level.