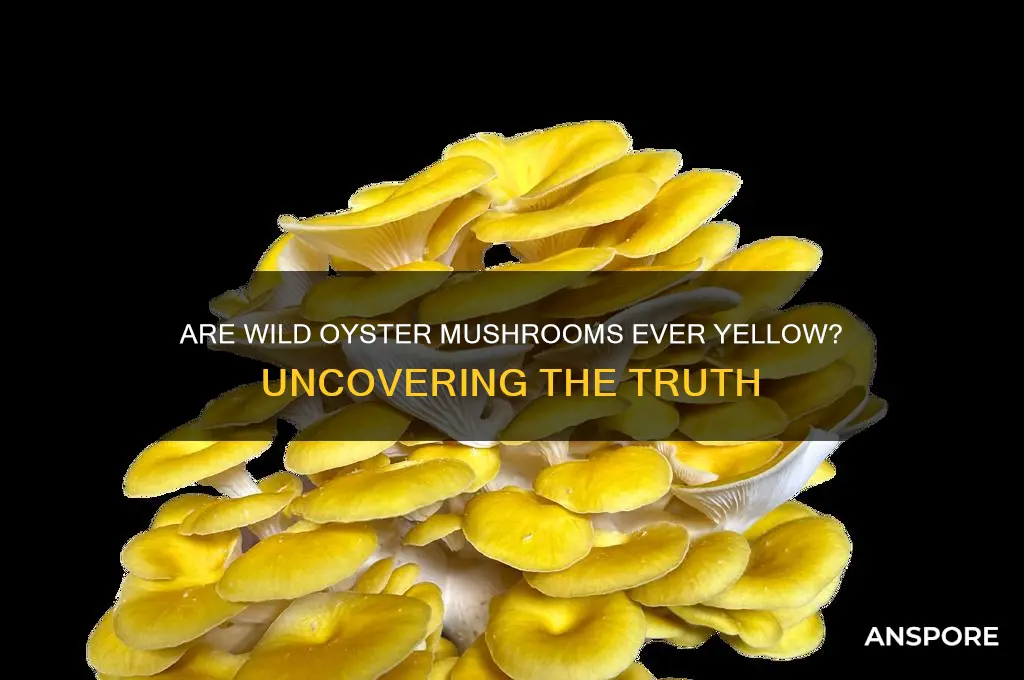

Wild oyster mushrooms, scientifically known as *Pleurotus ostreatus*, are typically recognized for their distinctive fan-like caps and shades of gray, brown, or tan. However, it is not uncommon for these mushrooms to exhibit variations in color, including yellow hues. Such variations can occur due to factors like genetic diversity, environmental conditions, or exposure to sunlight. While yellow wild oyster mushrooms are less frequently encountered, they are indeed a natural occurrence and remain edible, provided they are correctly identified and harvested from safe environments. Always exercise caution and consult a reliable guide or expert when foraging for wild mushrooms to ensure safety and accuracy.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Color | Wild oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) are typically grayish-brown to brown, but they can indeed be yellow. The yellow coloration is less common and may vary based on environmental factors such as substrate, humidity, and light exposure. |

| Species | Pleurotus ostreatus (common oyster mushroom) and other Pleurotus species can exhibit yellow hues, though it is not the standard color. |

| Edibility | Yellow oyster mushrooms are generally safe to eat, provided they are correctly identified and not confused with toxic species. Always verify with a reliable guide or expert. |

| Habitat | Found on dead or decaying wood, often in forests. Yellow variants may appear in specific conditions favoring pigment changes. |

| Season | Typically grows in spring and fall, but yellow forms may be more sporadic and dependent on environmental conditions. |

| Texture | Gills and caps may have a slightly different texture due to pigment variations, but overall similar to standard oyster mushrooms. |

| Taste | Flavor profile remains similar to other oyster mushrooms, mild and slightly sweet, regardless of color. |

| Identification | Yellow oyster mushrooms should be identified carefully to avoid confusion with toxic look-alikes like certain Amanita species. |

| Cultivation | Yellow variants can be cultivated, and some strains are specifically bred for their unique color. |

| Nutritional Value | Similar to other oyster mushrooms, rich in protein, vitamins, and minerals, regardless of color. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Natural Variations in Oyster Mushrooms

Wild oyster mushrooms, scientifically known as *Pleurotus ostreatus*, exhibit a surprising range of colors beyond the typical grayish-brown hues commonly associated with them. While less frequent, yellow varieties do exist in the wild, often causing foragers to pause and question their identification. These variations are not anomalies but natural expressions of the species’ adaptability to different environments. Factors such as sunlight exposure, temperature, and substrate composition can influence pigmentation, leading to yellower caps in certain specimens. Foragers should note that while yellow oyster mushrooms are edible, proper identification is crucial to avoid toxic look-alikes like the sulfur tuft (*Hypholoma fasciculare*).

To understand these color variations, consider the role of carotenoids, pigments responsible for yellow, orange, and red hues in many fungi. In oyster mushrooms, increased carotenoid production can result from prolonged exposure to sunlight, which acts as a stressor, prompting the mushroom to protect itself by producing more pigments. This phenomenon is similar to how leaves change color in autumn. Foragers in regions with higher sunlight intensity, such as open woodlands or forest edges, are more likely to encounter these yellow variants. However, this does not mean all yellow mushrooms in these areas are oyster mushrooms, emphasizing the need for careful examination of gill structure and spore color.

Cultivators can also intentionally produce yellow oyster mushrooms by manipulating growing conditions. For instance, exposing mycelium to controlled light stress during fruiting can enhance carotenoid production, resulting in brighter caps. This technique is often used in commercial cultivation to create visually appealing products. Home growers can experiment with this by placing mushroom kits near windows or using artificial lighting with higher blue wavelengths, which mimic sunlight. However, maintaining proper humidity and temperature remains critical to prevent contamination or stunted growth.

Comparatively, yellow oyster mushrooms are not as common as their gray or brown counterparts, making them a unique find in the wild. Their rarity adds to their allure, both for foragers and chefs, who appreciate their vibrant color and slightly nuttier flavor profile. When cooking, these mushrooms retain their hue, making them an excellent choice for dishes where visual appeal is as important as taste. Pairing them with ingredients like lemon, garlic, and thyme enhances their natural flavors without overpowering their delicate texture. Always cook wild mushrooms thoroughly to ensure safety, regardless of color.

In conclusion, the natural variations in oyster mushrooms, including yellow specimens, highlight the species’ remarkable adaptability and the intricate interplay between genetics and environment. Whether encountered in the wild or cultivated at home, these variations offer both scientific insight and culinary inspiration. By understanding the factors influencing pigmentation, foragers and growers alike can better appreciate and utilize these unique fungi, ensuring a safe and rewarding experience.

Testing for Magic Mushrooms: Methods, Risks, and Legal Considerations

You may want to see also

Yellowing Causes: Age or Environment

Wild oyster mushrooms, typically recognized by their creamy to grayish hues, can indeed exhibit yellow tones, sparking curiosity about the underlying causes. This yellowing is not merely a random occurrence but often a result of specific factors tied to age or environmental conditions. Understanding these factors is crucial for foragers, cultivators, and enthusiasts alike, as it impacts identification, safety, and cultivation practices.

Age-Related Yellowing: A Natural Process

As oyster mushrooms mature, their color can shift due to biochemical changes. Younger specimens often display lighter shades, while older ones may develop yellow or brownish tones. This is primarily due to the breakdown of pigments like melanins and the accumulation of carotenoids, which are naturally present in the mushroom’s tissue. For instance, *Pleurotus ostreatus*, a common wild oyster mushroom, tends to yellow around 7–10 days after reaching full maturity. Foragers should note that while age-related yellowing is natural, it may indicate tougher texture and reduced flavor, making younger specimens more desirable for culinary use.

Environmental Triggers: External Influences at Play

Environmental factors play a significant role in yellowing, often overshadowing age-related changes. Exposure to sunlight, for example, can accelerate pigment degradation, leading to rapid yellowing. This is particularly evident in mushrooms growing on sunlit logs or trees. Similarly, temperature fluctuations and humidity levels can stress the mushroom, causing it to produce enzymes that alter its color. A study found that oyster mushrooms exposed to temperatures above 25°C (77°F) for prolonged periods exhibited yellowing within 48 hours. Cultivators can mitigate this by maintaining optimal growing conditions: 18–22°C (64–72°F) and 60–70% humidity.

Comparative Analysis: Age vs. Environment

Distinguishing between age- and environment-induced yellowing requires careful observation. Age-related yellowing is gradual and uniform, affecting the entire mushroom cap and stem. In contrast, environmental yellowing often appears patchy or localized, particularly on areas exposed to direct sunlight or extreme conditions. For example, a mushroom growing on the south side of a log may show yellowing only on the sun-facing side, while the rest remains pale. This distinction is vital for safety, as environmental stress can sometimes lead to the accumulation of toxins, though this is rare in oyster mushrooms.

Practical Tips for Identification and Cultivation

For foragers, inspecting the mushroom’s habitat provides clues: mushrooms in shaded, stable environments are less likely to yellow due to external factors. Cultivators can prevent yellowing by using shade cloth to protect mushrooms from direct sunlight and monitoring temperature and humidity with digital sensors. Harvesting oyster mushrooms within 5–7 days of maturity ensures optimal color and texture. If yellowing occurs, it’s not necessarily a cause for alarm, but always cross-reference with other identification features to avoid confusion with toxic species.

In summary, yellowing in wild oyster mushrooms is a multifaceted phenomenon driven by age and environmental conditions. By understanding these factors, enthusiasts can better identify, cultivate, and appreciate these versatile fungi. Whether in the wild or a controlled setting, awareness of these causes ensures a safer and more rewarding experience.

Growing Mushrooms Indoors: Tips for Cultivating in Closed Spaces

You may want to see also

Edibility of Yellow Wild Oysters

Wild oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) are typically recognized by their grayish-brown caps, but variations in color, including yellow, do exist. These yellow variants, often referred to as "golden oysters" (Pleurotus citrinopileatus), are a distinct species known for their vibrant hue and delicate flavor. While both species are edible, the edibility of yellow wild oysters warrants specific attention due to their unique characteristics and potential risks.

Identification and Safety

Accurate identification is critical when foraging for yellow wild oysters. Their bright yellow caps and decurrent gills resemble other species, including the toxic *Omphalotus olearius* (Jack-O’-Lantern mushroom), which can cause severe gastrointestinal distress. Key distinguishing features include the absence of a ring on the stem and the lack of bioluminescence in golden oysters. Always consult a field guide or expert if uncertain, as misidentification can lead to poisoning.

Culinary Uses and Preparation

Yellow wild oysters are highly prized in culinary circles for their nutty flavor and tender texture. They are best sautéed or stir-fried to enhance their natural taste. Unlike their gray counterparts, golden oysters have a more delicate structure, so avoid overcooking to preserve their unique qualities. Pair them with light sauces or incorporate them into dishes like risottos or omelets for maximum flavor impact.

Nutritional Benefits and Cautions

These mushrooms are rich in protein, vitamins (B and D), and antioxidants, making them a nutritious addition to any diet. However, individuals with mushroom allergies or sensitivities should consume them in moderation. Start with small portions (50–100 grams per serving) to gauge tolerance. Additionally, always cook yellow wild oysters thoroughly, as consuming them raw may cause digestive discomfort due to their chitinous cell walls.

Foraging and Sustainability

When harvesting yellow wild oysters, prioritize sustainability by leaving some mushrooms to spore and ensure the ecosystem remains balanced. Avoid areas contaminated by pollutants or pesticides, as mushrooms readily absorb toxins. Foraging in pristine environments, such as hardwood forests, increases the likelihood of finding healthy specimens. Always follow local regulations and obtain necessary permits to forage legally.

In summary, yellow wild oysters are a delightful and edible find for foragers and chefs alike, but their consumption requires careful identification, proper preparation, and mindful harvesting practices. With these precautions in place, they can be a safe and flavorful addition to your culinary repertoire.

Can Morel Mushrooms Be Mistaken for False or Toxic Lookalikes?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Species Identification: Yellow vs. White

Wild oyster mushrooms, typically recognized by their fan-like caps and creamy white to grayish hues, can indeed present a yellow coloration, sparking curiosity and caution among foragers. This deviation from the expected palette often stems from species variation, environmental factors, or even mycelial aging. For instance, the Pleurotus citrinopileatus, commonly known as the golden oyster mushroom, boasts a vibrant yellow cap, distinguishing it from its white counterparts like Pleurotus ostreatus. Identifying these species accurately is crucial, as misidentification can lead to consuming toxic look-alikes, such as the Omphalotus olearius (Jack-O-Lantern mushroom), which also exhibits yellow tones but is poisonous.

To differentiate between yellow and white oyster mushrooms, start by examining the cap color and texture. Yellow oysters often have a brighter, more uniform yellow cap with a smoother surface, while white oysters tend to be more muted and may have slight gills or a velvety texture. Another key feature is the spore print: yellow oysters produce a white to pale yellow print, whereas white oysters yield a lilac-gray to pinkish print. Additionally, habitat plays a role—yellow oysters thrive in warmer climates and are often found on hardwoods like beech or oak, while white oysters are more adaptable and widespread.

Foraging safely requires a methodical approach. Always carry a field guide or use a reliable mushroom identification app to cross-reference findings. When in doubt, avoid consumption. A practical tip is to observe the mushroom’s reaction to touch: some yellow species, like the golden oyster, may bruise slightly when handled, whereas white oysters typically do not. For beginners, cultivating oyster mushrooms at home is a safer alternative, allowing for controlled observation of color variations without the risks of wild harvesting.

Environmental factors can also influence coloration. Exposure to sunlight or temperature fluctuations may cause white oysters to develop yellow patches, a phenomenon known as "sunburn." This does not necessarily indicate a different species but rather a stress response. To distinguish between natural variation and species difference, examine the mushroom’s overall morphology, including gill structure, stem thickness, and spore characteristics. A magnifying glass can be invaluable for this detailed inspection.

In conclusion, while yellow oyster mushrooms are a fascinating find, accurate identification is paramount. By focusing on cap color, spore prints, habitat, and environmental influences, foragers can confidently distinguish between species. Remember, the goal is not just to identify but to ensure safety. When in doubt, consult an expert or err on the side of caution—the forest will always offer another opportunity.

Transforming Mushroom Blocks: Can They Sprout Edible Mushrooms?

You may want to see also

Safety Concerns: Yellow Mushrooms Risks

Wild oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) are typically known for their grayish-brown caps, but variations in color, including yellow, can occur due to environmental factors, genetic mutations, or species misidentification. While some yellow oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus citrinopileatus) are cultivated and safe to eat, encountering a yellow wild mushroom raises safety concerns. Not all yellow mushrooms are edible, and misidentification can lead to severe consequences. For instance, the deadly Amanita species often present yellow or yellowish hues, making them a dangerous look-alike for foragers.

Analyzing the risks, the primary danger lies in the similarity between edible and toxic species. Yellow wild mushrooms may resemble the Jack-O-Lantern (Omphalotus olearius), which causes severe gastrointestinal distress, or the Sulphur Tuft (Hypholoma fasciculare), known for its toxic effects. Even experienced foragers can mistake these for edible varieties, especially in poor lighting or unfamiliar terrain. A single misidentified mushroom can cause symptoms ranging from nausea and vomiting to organ failure, depending on the toxin ingested. Always cross-reference findings with multiple reliable guides and consider consulting a mycologist.

To mitigate risks, follow these practical steps: First, avoid consuming any wild mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identification. Second, use a spore print test to determine the mushroom’s underside color, as this can differentiate between species. Third, document the mushroom’s habitat, as certain toxic species thrive in specific environments, such as decaying wood or coniferous forests. For example, the Jack-O-Lantern often grows in clusters on hardwood trees, while edible oyster mushrooms prefer dead or dying deciduous trees. Lastly, cook all mushrooms thoroughly, as some toxins are heat-sensitive, though this does not guarantee safety for poisonous species.

Comparatively, cultivated yellow oyster mushrooms are a safer alternative, as they are grown under controlled conditions and pose no risk of toxic look-alikes. However, wild foraging requires vigilance. For instance, the yellow-hued Velvet Foot (Flammulina velutipes) is edible but often confused with toxic species due to its similar color. Always err on the side of caution and discard any mushroom with uncertain identification. Remember, no meal is worth risking your health, and the consequences of a mistake can be irreversible.

In conclusion, while yellow wild mushrooms may pique curiosity, their risks far outweigh the rewards for inexperienced foragers. Toxic species like the Amanita or Jack-O-Lantern can cause life-threatening symptoms, and their resemblance to edible varieties makes misidentification a significant concern. By adhering to strict identification protocols, avoiding consumption of uncertain specimens, and prioritizing cultivated varieties, enthusiasts can enjoy mushrooms safely. When in doubt, throw it out—a simple rule that could save lives.

Can Wet Mushrooms Go Bad? Storage Tips and Shelf Life Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, wild oyster mushrooms can have yellow caps, though they are less common than the typical grayish-brown or tan varieties. The yellow coloration is due to natural variations in species like *Pleurotus citrinopileatus*, also known as the golden oyster mushroom.

Yes, yellow wild oyster mushrooms, such as *Pleurotus citrinopileatus*, are safe to eat and highly prized for their flavor. However, always ensure proper identification, as some toxic mushrooms may resemble oyster mushrooms in color.

Yellow wild oyster mushrooms typically have bright yellow caps, gills that are closely spaced, and a fan-like or oyster-shaped appearance. They often grow in clusters on wood. Confirm identification with a field guide or expert to avoid confusion with similar-looking species.