Algae, a diverse group of photosynthetic organisms, exhibit a wide range of reproductive strategies, and the question of whether they produce spores is a fascinating aspect of their biology. While not all algae form spores, many species do, particularly those in the groups of green algae (Chlorophyta) and red algae (Rhodophyta). These spores serve as a means of dispersal and survival, allowing algae to endure harsh environmental conditions and colonize new habitats. Spores in algae can be classified into various types, such as zoospores, which are motile and can swim to find suitable environments, and aplanospores, which are non-motile and rely on external factors for dispersal. Understanding the role of spores in algal reproduction provides valuable insights into their life cycles and ecological success.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do algae produce spores? | Yes, many algae species produce spores as part of their life cycle. |

| Types of spores | - Zygospores: Formed by the fusion of gametes in some algae (e.g., Zygnematophyceae). - Aplanospores: Non-motile spores produced asexually. - Zoospores: Motile spores with flagella, common in groups like Diatoms and Phaeophyceae. - Carpospores: Formed in the life cycle of red algae (Rhodophyta). - Tetraspores: Produced in the tetrasporic phase of red algae. |

| Function of spores | - Survival: Spores help algae survive harsh conditions (e.g., desiccation, temperature extremes). - Dispersal: Spores aid in spreading algae to new habitats. - Reproduction: Spores are involved in both sexual and asexual reproduction. |

| Life cycle involvement | Spores are a key stage in the alternation of generations (e.g., haploid and diploid phases) in many algae. |

| Examples of spore-producing algae | - Green algae (Chlorophyta): Some species produce zoospores or aplanospores. - Red algae (Rhodophyta): Produce carpospores and tetraspores. - Brown algae (Phaeophyceae): Produce zoospores. |

| Non-spore-producing algae | Some algae, like certain Cyanobacteria, do not produce spores and reproduce via other methods (e.g., fragmentation, akinetes). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Algae spore types: Different algae species produce unique spore types, each adapted to specific environments

- Spore formation process: Algae spores develop through specialized reproductive structures like sporangia or zygotes

- Spore dispersal methods: Algae spores spread via water, wind, or animals, ensuring species survival and colonization

- Dormancy in algae spores: Spores can remain dormant for years, reviving under favorable environmental conditions

- Ecological role of spores: Algae spores contribute to ecosystem balance, nutrient cycling, and biodiversity maintenance

Algae spore types: Different algae species produce unique spore types, each adapted to specific environments

Algae, often overlooked in the grand scheme of plant life, exhibit a remarkable diversity in their reproductive strategies, particularly through the production of spores. These spores are not one-size-fits-all; instead, they are finely tuned to the specific environments in which different algae species thrive. For instance, zyospores, produced by certain green algae like *Chlamydomonas*, are encased in a thick, protective wall that allows them to survive harsh conditions such as desiccation or extreme temperatures. This adaptation ensures their longevity in unpredictable habitats like temporary pools or soil crusts.

Consider the carpospores of red algae, such as those found in the genus *Porphyra*. These spores are formed within specialized structures called carpogonia and are crucial for the algae’s life cycle. Carpospores are often larger and more robust, enabling them to settle and grow in the turbulent, nutrient-rich environments of intertidal zones. Their size and structure reflect an evolutionary strategy to anchor firmly in rocky substrates, where wave action is constant.

In contrast, zoospores, common in brown algae like *Phaeophyceae*, are motile spores equipped with flagella. This mobility allows them to swim through water, seeking out optimal conditions for germination. Zoospores are particularly advantageous in aquatic environments where dispersal and rapid colonization are key to survival. Their short-lived nature is balanced by their ability to quickly establish new growth in favorable locations.

For a practical application, understanding these spore types can inform aquaculture practices. For example, when cultivating *Porphyra* (nori) for sushi production, farmers can optimize conditions for carpospore settlement by mimicking rocky intertidal environments. Similarly, in algal biofuel research, knowing the motility of zoospores can enhance the efficiency of algae cultivation systems by ensuring even distribution in large tanks.

In summary, the diversity of algae spore types is a testament to their adaptability. From the resilient zyospores to the motile zoospores and the robust carpospores, each spore type is a specialized tool in the algae’s survival kit. By studying these adaptations, we not only gain insight into algal biology but also unlock practical applications in industries ranging from aquaculture to biotechnology.

Can Spores Get Contaminated? Understanding Risks and Prevention Methods

You may want to see also

Spore formation process: Algae spores develop through specialized reproductive structures like sporangia or zygotes

Algae, often overlooked in discussions of spore-producing organisms, indeed form spores through intricate reproductive mechanisms. Unlike plants or fungi, algae exhibit a diverse range of spore types and formation processes, reflecting their evolutionary adaptability. Central to this process are specialized structures such as sporangia and zygotes, which serve as factories for spore development. Understanding these structures and their functions provides insight into algae’s survival strategies in varying environments.

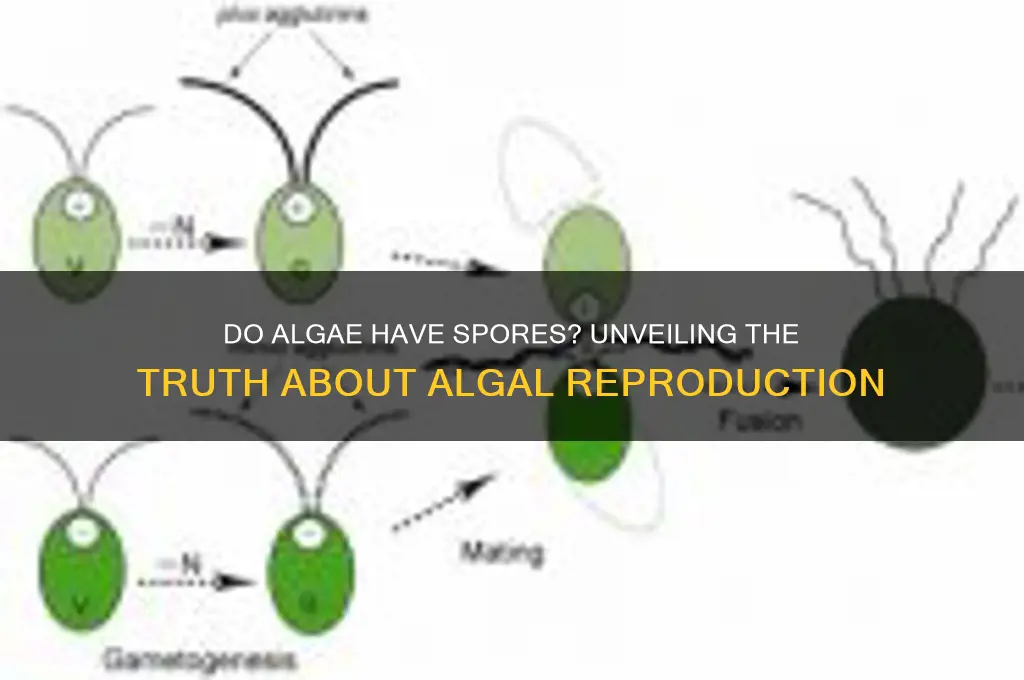

The spore formation process in algae begins with the development of sporangia, sac-like structures where spores are produced. In species like *Chlamydomonas*, sporangia form after the fusion of gametes, creating a zygote that undergoes meiosis to produce haploid spores. These spores are then released into the environment, where they can remain dormant until conditions favor germination. For instance, in green algae (*Ulva*), sporangia develop on the thallus, releasing spores that disperse through water currents. This mechanism ensures genetic diversity and enhances the species’ ability to colonize new habitats.

Zygotes also play a critical role in spore formation, particularly in algae with complex life cycles. In red algae (*Rhodophyta*), zygotes develop into carposporangia, which produce carpospores. These spores germinate into a new generation, showcasing a biphasic life cycle. Similarly, brown algae (*Phaeophyta*) produce zygotes that develop into structures like sporophytes, which release spores through meiosis. This alternation of generations highlights the sophistication of algae’s reproductive strategies, rivaling those of higher plants.

Practical applications of algae spore formation are evident in aquaculture and biotechnology. For example, *Haematococcus pluvialis*, a green alga, produces spores under stress conditions, which are harvested for astaxanthin production—a high-value antioxidant. To optimize spore yield, cultivators manipulate environmental factors such as light intensity and nutrient availability. In laboratories, spores are induced to germinate by adjusting pH levels (typically between 6.5 and 7.5) and temperature (20–25°C), ensuring controlled growth for research or commercial purposes.

In conclusion, the spore formation process in algae is a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. Through structures like sporangia and zygotes, algae produce spores that ensure survival, dispersal, and genetic diversity. Whether in natural ecosystems or industrial settings, understanding this process unlocks opportunities for conservation, biotechnology, and sustainable resource utilization. By studying these mechanisms, we gain not only scientific knowledge but also practical tools for harnessing algae’s potential.

Chanterelles' Spore Secrets: Unveiling the Mushroom's Reproduction Mystery

You may want to see also

Spore dispersal methods: Algae spores spread via water, wind, or animals, ensuring species survival and colonization

Algae, often overlooked in discussions of spore-producing organisms, employ diverse strategies to disperse their spores, ensuring survival and colonization across varied environments. Unlike plants, which rely heavily on wind or animal vectors, algae leverage their aquatic habitats to their advantage. Water, their primary medium, facilitates spore dispersal through currents, tides, and even the movement of aquatic organisms. This method is particularly effective for species like *Chara* (stoneworts) and *Ulva* (sea lettuce), which release spores directly into the water column. The fluid dynamics of their environment not only carry spores to new locations but also dilute them, reducing competition in the parent habitat.

Wind, though less dominant in aquatic ecosystems, still plays a role in spore dispersal for algae that inhabit shallow or intertidal zones. Species like *Enteromorpha* (green algae) produce lightweight spores that can be carried short distances by air currents, especially during low tide when they are exposed to the atmosphere. This dual adaptation—utilizing both water and wind—highlights the versatility of algal spore dispersal mechanisms. For instance, spores of *Cladophora* can adhere to surfaces or form buoyant structures, increasing their chances of being transported by wind or water depending on environmental conditions.

Animals, both aquatic and terrestrial, act as inadvertent carriers of algal spores, further expanding their dispersal range. Zoospores, motile spores propelled by flagella, can attach to the bodies of fish, crustaceans, or birds, hitching a ride to new habitats. Similarly, spores may adhere to the fur or feathers of terrestrial animals that frequent coastal areas. This method is particularly effective for algae like *Prasiola*, which thrive in bird-frequented environments. The role of animals in spore dispersal underscores the interconnectedness of ecosystems and the passive yet ingenious strategies algae employ to colonize new territories.

Understanding these dispersal methods has practical implications for conservation and aquaculture. For instance, in restoring algal populations in degraded marine ecosystems, introducing spores via water currents can mimic natural dispersal patterns, enhancing colonization success. Similarly, managing animal movement in aquaculture settings can prevent the unintentional spread of invasive algal species. By studying these mechanisms, scientists can develop targeted strategies to protect native algae while controlling unwanted species, ensuring the health and balance of aquatic ecosystems.

In conclusion, the spore dispersal methods of algae—via water, wind, and animals—are finely tuned to their environments, ensuring species survival and colonization. These strategies not only highlight the adaptability of algae but also provide valuable insights for ecological management and conservation efforts. Whether through the gentle flow of a stream, the gust of a coastal breeze, or the unwitting assistance of a passing animal, algal spores continue their journey, perpetuating life in some of the planet’s most dynamic ecosystems.

Mold Spores in Gainesville, Florida: Are Levels High?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Dormancy in algae spores: Spores can remain dormant for years, reviving under favorable environmental conditions

Algae, often overlooked in discussions of plant biology, possess a remarkable survival strategy: the production of spores capable of dormancy. These spores can remain inactive for years, even decades, waiting for the right environmental cues to revive and grow. This ability is not just a biological curiosity; it has significant implications for ecosystems, industries, and even climate science. Understanding how and why algae spores enter dormancy can unlock insights into their resilience and adaptability.

Consider the process of spore dormancy as a biological time capsule. When conditions become unfavorable—such as extreme temperatures, drought, or nutrient scarcity—algae produce spores that shut down metabolic activity. These spores are often encased in protective layers, shielding them from environmental stressors. For example, *Chlamydomonas*, a common green alga, forms zygospores that can withstand desiccation and freezing temperatures. Once conditions improve—perhaps after a rainstorm or seasonal shift—these spores germinate, restoring the algal population. This mechanism ensures survival across generations, even in unpredictable habitats like ephemeral pools or polar ice edges.

From a practical standpoint, harnessing algal spore dormancy could revolutionize industries like aquaculture and biotechnology. For instance, dormant spores of *Dunaliella salina*, a salt-tolerant alga rich in beta-carotene, could be stored and activated on demand for commercial production. Similarly, in wastewater treatment, dormant algal spores could be used to rapidly colonize polluted waters when conditions become favorable for growth. However, activating dormant spores requires precision: factors like light intensity, pH, and nutrient availability must be carefully calibrated. For optimal results, a gradual increase in light exposure (e.g., from 50 to 200 μmol/m²/s over 48 hours) and a pH range of 7.0–8.5 are recommended.

Comparatively, algal spore dormancy shares similarities with seed banks in higher plants but operates on a faster timescale. While plant seeds may remain dormant for centuries, algal spores typically revive within weeks or months. This rapid response allows algae to exploit transient environments, such as seasonal blooms in nutrient-rich waters. However, unlike plants, algae often lack complex structures to regulate dormancy, relying instead on external triggers like temperature shifts or salinity changes. This simplicity makes algal spores both vulnerable and versatile, adapting to a wide range of ecological niches.

In conclusion, dormancy in algal spores is a testament to the ingenuity of nature’s survival strategies. By remaining dormant for years, these spores ensure the persistence of algal species in the face of environmental challenges. For researchers and practitioners, understanding this mechanism opens doors to innovative applications, from sustainable resource production to ecological restoration. Whether in a laboratory or a natural habitat, the revival of dormant algal spores underscores their potential as both a scientific marvel and a practical tool.

Where to Buy Psilocybin Spores Legally: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Ecological role of spores: Algae spores contribute to ecosystem balance, nutrient cycling, and biodiversity maintenance

Algae spores are microscopic time capsules, each one a dormant reservoir of genetic potential. These resilient structures allow algae to survive harsh conditions, from desiccation to extreme temperatures, ensuring their persistence across diverse ecosystems. But their role extends far beyond mere survival. Algae spores are key players in maintaining ecological balance, driving nutrient cycling, and fostering biodiversity.

Understanding their ecological function reveals a sophisticated network of interactions that underpin the health of aquatic and terrestrial environments.

Consider nutrient cycling, a fundamental process for ecosystem productivity. When algae spores germinate, they rapidly absorb nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus from their surroundings. This uptake helps prevent excessive nutrient accumulation, which can lead to harmful algal blooms and eutrophication. For instance, in freshwater systems, diatom spores contribute to nutrient regulation by sequestering phosphorus, a common pollutant from agricultural runoff. Conversely, during periods of nutrient scarcity, spore germination can release stored nutrients back into the environment, acting as a natural fertilizer. This dual role highlights the dynamic contribution of algae spores to nutrient balance.

The dispersal of algae spores also plays a critical role in maintaining biodiversity. Spores can travel vast distances via wind, water, or animal vectors, colonizing new habitats and preventing monocultures. In marine ecosystems, for example, the dispersal of kelp spores ensures genetic diversity across kelp forests, which are vital habitats for numerous species. Similarly, in soil ecosystems, algae spores contribute to microbial diversity, enhancing soil health and supporting plant growth. This dispersal mechanism not only sustains local ecosystems but also facilitates adaptation to changing environmental conditions, a crucial aspect of resilience in the face of climate change.

To harness the ecological benefits of algae spores, practical strategies can be implemented. In aquaculture, controlled spore release can be used to manage water quality and prevent algal blooms. For instance, introducing specific algae species known for their nutrient-absorbing capabilities can mitigate pollution in fish farms. In agriculture, incorporating algae-rich biofertilizers can improve soil fertility while reducing reliance on chemical inputs. Additionally, conservation efforts should focus on preserving spore-dispersal pathways, such as maintaining riparian zones and reducing air pollution, to ensure the continued functioning of these ecological processes.

In conclusion, algae spores are not just survival mechanisms but active contributors to ecosystem health. Their role in nutrient cycling, biodiversity maintenance, and habitat colonization underscores their importance in both natural and managed environments. By understanding and leveraging these processes, we can develop sustainable practices that enhance ecosystem resilience and productivity. The humble algae spore, often overlooked, is a cornerstone of ecological balance, deserving of greater attention in environmental research and management.

Prevent Mold Growth: Can Mattress Covers Block Spores Effectively?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, many algae species produce spores as part of their life cycle for reproduction and dispersal.

Algae produce various types of spores, including zoospores (motile spores), aplanospores (non-motile spores), and resting spores, depending on the species and environmental conditions.

Algae spores are often simpler in structure and function compared to plant spores. They are typically unicellular or consist of a few cells, while plant spores are part of a more complex life cycle involving alternation of generations.

No, not all algae produce spores. Some algae reproduce solely through vegetative methods like fragmentation or the release of gametes, while others have spore-producing stages in their life cycles.

Spores in algae serve as a means of dispersal, survival in unfavorable conditions, and genetic diversity. They allow algae to colonize new habitats and persist through harsh environments.