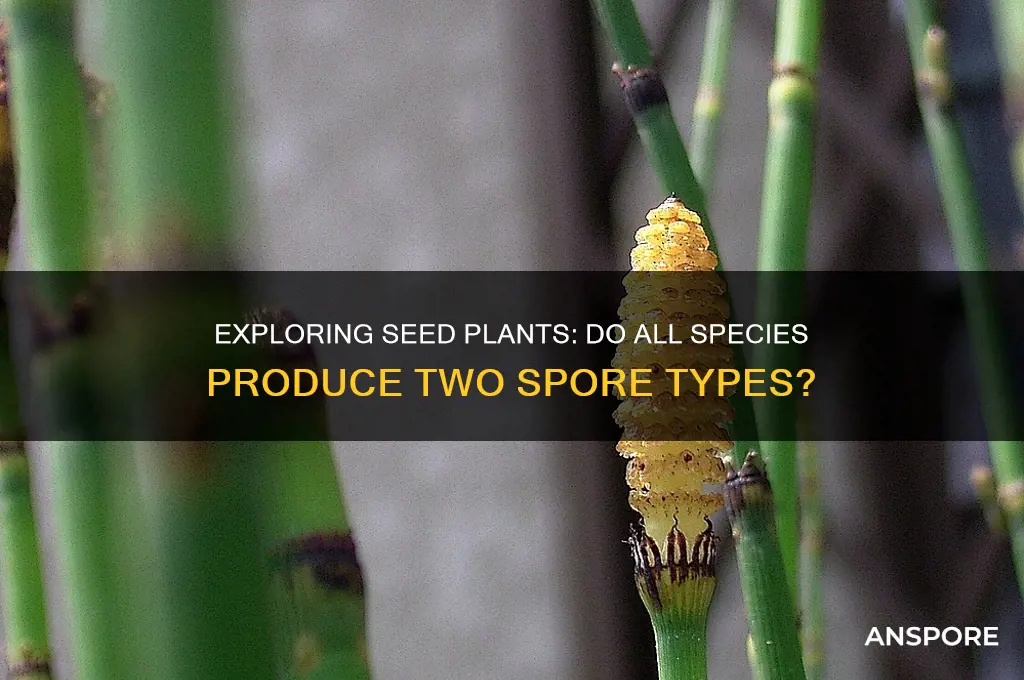

Seed plants, a diverse group that includes gymnosperms and angiosperms, are characterized by their ability to produce seeds for reproduction. A fundamental aspect of their life cycle involves the formation of spores, which are crucial for alternation of generations. However, not all seed plants form two types of spores. While non-seed plants like ferns typically produce two distinct spore types (microspores and megaspores), seed plants have evolved to produce only one functional type of spore in their reproductive structures. In seed plants, the microspores develop into pollen grains, which ultimately give rise to male gametophytes, while the megaspores develop into the female gametophytes within the ovules. This specialization reflects the adaptation of seed plants to more efficient and protected reproductive strategies, distinguishing them from their non-seed plant ancestors.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do all seed plants form two types of spores? | No, not all seed plants form two types of spores. |

| Types of Seed Plants | 1. Gymnosperms: Typically form two types of spores (microspores and megaspores). 2. Angiosperms: Do not form spores; they produce seeds directly from flowers. |

| Spores in Gymnosperms | - Microspores: Develop into male gametophytes (pollen grains). - Megaspores: Develop into female gametophytes (within ovules). |

| Angiosperms and Spores | Angiosperms (flowering plants) do not produce spores; they reproduce via seeds formed from fertilization in flowers. |

| Key Distinction | Gymnosperms rely on spores for reproduction, while angiosperms bypass the spore stage and produce seeds directly. |

| Examples | - Gymnosperms: Conifers (e.g., pines), cycads, ginkgo. - Angiosperms: Roses, oaks, wheat, sunflowers. |

| Evolutionary Context | Seed plants (spermatophytes) evolved from spore-producing plants, but angiosperms evolved a more direct reproductive strategy. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Alternation of Generations in Seed Plants

Seed plants, including gymnosperms and angiosperms, exhibit a unique life cycle known as alternation of generations, where the plant alternates between a diploid sporophyte and a haploid gametophyte phase. Unlike ferns and mosses, which produce two distinct types of spores (microspores and megaspores), seed plants have evolved a more specialized reproductive strategy. In seed plants, the sporophyte generation is dominant and long-lived, while the gametophyte generation is reduced and dependent on the sporophyte for nutrition. This adaptation has been key to their success in diverse environments.

Consider the process of spore formation in seed plants. The sporophyte produces two types of spores, but these are not free-living, as in non-seed plants. Instead, they develop into male and female gametophytes within the confines of the cone or flower. For example, in pine trees (gymnosperms), microspores develop into pollen grains, which are the male gametophytes, while megaspores develop into the female gametophytes within the ovule. This internal development of gametophytes is a critical distinction from plants that release spores into the environment.

The alternation of generations in seed plants is further characterized by the protection and nourishment of the gametophytes. In angiosperms, the female gametophyte (embryo sac) is enclosed within the ovule, which later develops into a seed. The male gametophyte (pollen grain) is transported to the female reproductive structure, often via wind or animals, where it germinates to produce sperm. This dependency on the sporophyte for protection and nutrient supply highlights the evolutionary shift toward seed-based reproduction, reducing reliance on external water for fertilization.

Practical observations of this cycle can be made by examining the reproductive structures of common seed plants. For instance, dissecting a flower reveals the ovary containing ovules, each housing a female gametophyte. Similarly, examining a pine cone shows microsporangia and megasporangia, where spores develop. Understanding this cycle is crucial for horticulture and agriculture, as it informs practices like pollination management and seed production. For example, hand-pollination in greenhouses relies on knowledge of when and how male and female gametophytes are ready for fertilization.

In conclusion, while seed plants do not form two types of free-living spores like ferns or mosses, their alternation of generations involves specialized spores that develop into dependent gametophytes. This adaptation has enabled seed plants to dominate terrestrial ecosystems by ensuring reproductive success in varied conditions. By studying this cycle, we gain insights into plant evolution and practical applications in plant cultivation and conservation.

Hydrogen Peroxide's Power: Can It Effectively Kill Mold Spores?

You may want to see also

Microspores vs. Megaspores Formation

Seed plants, encompassing gymnosperms and angiosperms, universally engage in the production of two distinct spore types: microspores and megaspores. This heterospory is a cornerstone of their reproductive strategy, ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability. Microspores, smaller in size, develop into male gametophytes, while megaspores, larger, give rise to female gametophytes. This division of labor is critical for the sexual reproduction of seed plants, setting them apart from more primitive plant groups like ferns and mosses, which produce only one type of spore.

The formation of microspores and megaspores occurs within specialized structures: microsporangia and megasporangia, respectively. In angiosperms, these are housed within the anthers and ovules of flowers, while in gymnosperms, they are found in cones. Microsporogenesis involves the meiotic division of microspore mother cells within the microsporangia, producing four haploid microspores. Each microspore then develops into a pollen grain, the male gametophyte. Megasporogenesis, more complex, typically involves the production of a single functional megaspore from a megaspore mother cell via meiosis, though the process can vary among species. This megaspore develops into the female gametophyte, which houses the egg cell.

A key difference in the formation process lies in the number of spores produced and their fate. Microsporogenesis is prolific, generating numerous microspores to increase the chances of successful pollination. In contrast, megasporogenesis is more conservative, often resulting in a single functional megaspore per megasporangium. This disparity reflects the differing reproductive roles: male gametophytes are expendable and produced in abundance, while female gametophytes are resource-intensive and produced sparingly.

Practical observations of these processes can be made through microscopy. For instance, examining anther cross-sections from flowering plants reveals microspores in various developmental stages, from tetrads to mature pollen grains. Similarly, ovule dissections can showcase the megaspore mother cell and the subsequent development of the female gametophyte. Such hands-on exploration underscores the precision and efficiency of spore formation in seed plants.

In conclusion, the formation of microspores and megaspores is a finely tuned process that underscores the reproductive success of seed plants. Understanding these mechanisms not only highlights the evolutionary sophistication of heterospory but also provides practical insights for fields like botany, agriculture, and conservation. By appreciating the nuances of microspore and megaspore formation, we gain a deeper understanding of the intricate balance between male and female reproductive strategies in the plant kingdom.

Blocking with Spore Frog: Can You Sac It Post-Block?

You may want to see also

Role of Pollen and Ovules

Seed plants, encompassing gymnosperms and angiosperms, are characterized by their ability to produce seeds, a trait that has significantly contributed to their evolutionary success. Central to this process are pollen and ovules, which play distinct yet interdependent roles in reproduction. Pollen, the male gametophyte, is produced in the anthers of flowers or microsporangia of cones. It contains the sperm cells necessary for fertilization. Ovules, the female reproductive structures, develop within the ovary of flowers or ovulate cones and house the egg cells. Together, they ensure the continuation of seed plant lineages through sexual reproduction.

The interaction between pollen and ovules is a finely tuned process. Pollination, the transfer of pollen to the stigma of a flower or directly to the ovule in gymnosperms, initiates a series of events. In angiosperms, the pollen grain germinates, producing a pollen tube that grows through the style to reach the ovule. In gymnosperms, pollen lands on the micropyle of the ovule and similarly forms a pollen tube. This mechanism ensures the delivery of sperm to the egg, culminating in fertilization. The resulting zygote develops into an embryo, while the ovule matures into a seed, encapsulating the next generation.

From an ecological perspective, pollen and ovules are critical for genetic diversity. Pollen dispersal, facilitated by wind, water, or animals, allows for cross-fertilization between individuals, promoting genetic recombination. This diversity enhances the adaptability of plant populations to changing environments. For instance, wind-pollinated plants like pines produce vast quantities of lightweight pollen to increase the likelihood of successful fertilization, while animal-pollinated plants like orchids invest in specialized structures to attract specific pollinators.

Practical considerations highlight the importance of pollen and ovules in agriculture and horticulture. For crop plants, understanding pollen viability and ovule receptivity is essential for maximizing yield. Techniques such as hand pollination or the use of controlled environments can mitigate poor natural pollination rates. For example, in greenhouses, tomato growers often use vibrating devices to simulate bee activity, ensuring effective pollen release and transfer. Similarly, in orchards, the strategic planting of compatible varieties enhances cross-pollination, leading to better fruit set.

In conclusion, the role of pollen and ovules in seed plants is both fundamental and multifaceted. They are the linchpins of sexual reproduction, ensuring genetic continuity and diversity. Their interplay is a testament to the sophistication of plant reproductive strategies, adapted over millennia to thrive in diverse ecosystems. Whether in natural habitats or cultivated fields, the success of seed plants hinges on the delicate balance and functionality of these reproductive structures.

Are Magic Mushroom Spores Legal in Nevada? Exploring the Law

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Heterospory in Seed Plant Evolution

Seed plants, a diverse group encompassing gymnosperms and angiosperms, are characterized by their ability to produce seeds, a trait that has significantly contributed to their success in various ecosystems. However, not all seed plants form two types of spores, a phenomenon known as heterospory. This evolutionary innovation is a key aspect of seed plant diversity and adaptation. Heterospory involves the production of two distinct spore types: microspores, which develop into male gametophytes, and megaspores, which give rise to female gametophytes. This differentiation is a critical step in the evolution of seed plants, as it allows for more efficient reproduction and greater adaptability to different environments.

The Origins of Heterospory

Heterospory first emerged in the Devonian period, approximately 385 million years ago, among the ancestors of modern seed plants. Fossil evidence suggests that early heterosporous plants, such as the genus *Baragwanathia*, exhibited small microspores and larger megaspores. This size difference is functionally significant: smaller microspores can be produced in greater quantities, enhancing the chances of successful pollination, while larger megaspores provide more resources for the developing embryo, increasing survival rates. The evolution of heterospory is closely linked to the development of ovules, which eventually led to the formation of seeds. By encapsulating the megaspore within a protective structure, plants reduced their dependence on water for reproduction, enabling colonization of drier habitats.

Mechanisms and Advantages

The mechanism of heterospory involves genetic and developmental changes that regulate spore size and function. In gymnosperms like conifers, microspores are produced in pollen cones, while megaspores develop in ovulate cones. Angiosperms further refine this process, with microspores forming pollen grains and megaspores developing into embryo sacs within flowers. The advantages of heterospory are manifold. Firstly, it allows for more efficient resource allocation, as the larger megaspore can support the initial growth of the embryo. Secondly, it facilitates the evolution of pollination strategies, such as wind and animal pollination, which enhance genetic diversity. Lastly, heterospory is a prerequisite for the development of seeds, which provide protection and nourishment to the developing plant, ensuring higher survival rates in diverse environments.

Comparative Analysis: Heterospory Across Seed Plants

While all seed plants exhibit heterospory, the degree of specialization varies. Gymnosperms, such as pines and cycads, retain a more primitive form of heterospory, with exposed ovules and reliance on wind pollination. In contrast, angiosperms have evolved highly specialized reproductive structures, including flowers and fruits, which maximize reproductive success. For example, orchids have developed intricate pollination mechanisms involving specific animal pollinators, while grasses produce vast quantities of lightweight pollen to ensure widespread dispersal. These differences highlight how heterospory has been adapted to suit the ecological niches of various seed plant groups.

Practical Implications and Future Research

Understanding heterospory has practical applications in agriculture and conservation. For instance, knowledge of spore development can inform breeding programs aimed at improving crop resilience and yield. Additionally, studying heterospory in endangered plant species can provide insights into their reproductive biology, aiding conservation efforts. Future research should focus on the genetic basis of heterospory, particularly the genes regulating spore size and differentiation. Advances in genomics and developmental biology could reveal how this trait evolved and how it can be manipulated to address challenges such as climate change and food security. By unraveling the mysteries of heterospory, scientists can unlock new strategies for sustainable plant management and biodiversity preservation.

Can Mold Spores Stick to Your Clothes? Facts and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Exceptions in Seed Plant Reproduction

Seed plants, encompassing gymnosperms and angiosperms, are traditionally known for their alternation of generations, where two types of spores—microspores and megaspores—play pivotal roles in reproduction. However, not all seed plants adhere strictly to this binary spore system. Exceptions exist, particularly in certain gymnosperm groups, where reproductive strategies diverge from the norm. For instance, some cycads and Ginkgo biloba exhibit unique spore development patterns that challenge the universal applicability of the two-spore model. These exceptions highlight the evolutionary diversity and adaptability of seed plant reproduction.

Consider the cycads, ancient plants often referred to as "living fossils." Unlike most seed plants, cycads produce only one functional megaspore per megasporangium, rather than the typical four. This megaspore then develops into a female gametophyte, which is significantly larger and more complex than those of other seed plants. This deviation from the standard four-megaspore pattern underscores the cycads' distinct reproductive biology. Similarly, Ginkgo biloba, another relic species, forms megasporangia that produce only one functional megaspore, further illustrating how some seed plants break the mold of the two-spore paradigm.

From an analytical perspective, these exceptions can be attributed to evolutionary adaptations to specific ecological niches. Cycads and Ginkgo, for example, have persisted in relatively stable environments for millions of years, allowing their reproductive systems to diverge from those of more widespread seed plants. Their unique spore development may reflect a trade-off between energy efficiency and reproductive success in their respective habitats. This suggests that while the two-spore system is common, it is not a universal requirement for seed plant reproduction.

For those studying or cultivating these exceptional plants, understanding their reproductive quirks is essential. For instance, when propagating cycads, it’s crucial to account for their single functional megaspore, as this affects seed production and viability. Similarly, Ginkgo growers should be aware of its distinct megasporangium structure to optimize pollination efforts. Practical tips include monitoring environmental conditions closely, as these relic species often thrive in specific temperature and humidity ranges. For cycads, maintaining soil pH between 5.0 and 6.5 can enhance nutrient uptake, while Ginkgo benefits from well-draining soil and full sunlight.

In conclusion, while the two-spore system is a hallmark of seed plant reproduction, exceptions like cycads and Ginkgo biloba demonstrate the flexibility and diversity of plant reproductive strategies. These deviations are not anomalies but rather evolutionary adaptations that have allowed these species to survive and thrive in their unique ecological contexts. By studying these exceptions, we gain deeper insights into the complexity of plant reproduction and the factors driving evolutionary divergence. Whether for academic research or practical horticulture, recognizing these exceptions enriches our understanding of the natural world.

Are Mold Spores Alive? Unveiling the Truth About Fungal Life

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all seed plants form two types of spores. Seed plants, including gymnosperms (like pines) and angiosperms (flowering plants), produce seeds directly and do not rely on spores for reproduction. However, some seed plants, like certain gymnosperms, may produce spores during their life cycle, but this is not universal.

Seed plants reproduce using seeds, which contain an embryo, while plants that form two types of spores (like ferns and mosses) reproduce via alternation of generations, producing both male (microspores) and female (megaspores) spores. Seed plants have evolved to bypass the spore-dependent reproductive stage.

Yes, some seed plants, particularly gymnosperms like conifers, produce spores during their life cycle. For example, conifers produce pollen (microspores) and ovules (containing megaspores), but these spores are part of the process leading to seed formation, not the primary reproductive method.