Not all microorganisms produce spores; this ability is specific to certain types of bacteria, fungi, and some protozoa. Spores are highly resistant, dormant structures that enable these organisms to survive harsh environmental conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, and lack of nutrients. For example, bacterial species like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* form endospores, while fungal species such as *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* produce spores as part of their reproductive cycle. However, many microorganisms, including most viruses, archaea, and many other bacteria, do not form spores and rely on other mechanisms for survival and dispersal. Thus, spore formation is a specialized adaptation rather than a universal trait among microorganisms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do all microorganisms make spores? | No, not all microorganisms produce spores. |

| Microorganisms that form spores | Bacteria (e.g., Bacillus, Clostridium), Fungi (e.g., Aspergillus, Penicillium), Some Protists (e.g., certain algae), Few Microalgae. |

| Microorganisms that do not form spores | Most bacteria (non-sporulating), Yeasts, Most viruses, Most protozoa, Most microalgae. |

| Purpose of spore formation | Survival in harsh conditions (e.g., heat, desiccation, chemicals), Long-term dormancy, Dispersal to new environments. |

| Spore types | Endospores (bacterial), Exospores (fungal), Cysts (protozoan), Akinetes (cyanobacterial). |

| Key differences | Spores are highly resistant and metabolically inactive, while non-spore-forming microorganisms are generally more susceptible to environmental stresses. |

| Latest research (as of 2023) | Ongoing studies focus on spore resistance mechanisms, applications in biotechnology, and environmental survival strategies. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Bacterial Sporulation Mechanisms: How and why certain bacteria form spores for survival in harsh conditions

- Fungal Spore Formation: Processes fungi use to produce spores for reproduction and dispersal

- Non-Spore Forming Microbes: Microorganisms that lack spore-forming abilities and their survival strategies

- Environmental Triggers for Sporulation: Factors like nutrient depletion or heat that induce spore formation

- Medical Significance of Spores: Role of microbial spores in infections, diseases, and antibiotic resistance

Bacterial Sporulation Mechanisms: How and why certain bacteria form spores for survival in harsh conditions

Not all microorganisms form spores, but among those that do, bacteria stand out for their remarkable ability to enter a dormant state through sporulation. This process is a survival strategy employed by certain bacterial species, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, to endure extreme environmental conditions. Unlike vegetative cells, spores are highly resistant to heat, desiccation, radiation, and chemicals, making them a critical adaptation for long-term survival in harsh habitats. Understanding the mechanisms of bacterial sporulation reveals how these microorganisms ensure their persistence in environments where other life forms might perish.

The sporulation process begins with an asymmetric cell division, where the bacterium divides into a larger mother cell and a smaller forespore. This division is tightly regulated by genetic signals, primarily the Spo0A protein, which activates the sporulation pathway in response to nutrient deprivation or other stressors. The forespore is then engulfed by the mother cell, forming a double-membrane structure. Within this protective compartment, the forespore undergoes a series of morphological changes, including the synthesis of a thick, multilayered spore coat and the accumulation of dipicolinic acid (DPA), a molecule that stabilizes the spore’s DNA and proteins. This intricate process ensures the spore’s resilience, allowing it to remain viable for years or even centuries.

From a practical standpoint, bacterial spores pose significant challenges in industries such as food preservation and healthcare. For instance, *Clostridium botulinum* spores can survive pasteurization temperatures, necessitating more stringent sterilization methods like autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes. Similarly, *Bacillus anthracis* spores, the causative agent of anthrax, can persist in soil for decades, making decontamination efforts difficult. Understanding sporulation mechanisms not only highlights bacterial adaptability but also informs strategies to control spore-forming pathogens, such as using spore-specific antimicrobials or improving sterilization protocols.

Comparatively, while some fungi and protozoa also form spores, bacterial sporulation is unique in its efficiency and resistance. Fungal spores, for example, are generally less resistant to extreme conditions than bacterial spores. This distinction underscores the evolutionary advantage of bacterial sporulation, particularly in environments where resources are scarce or conditions are unpredictable. By forming spores, these bacteria ensure their genetic continuity, even in the absence of favorable growth conditions, exemplifying nature’s ingenuity in overcoming survival challenges.

In conclusion, bacterial sporulation is a finely tuned survival mechanism that enables certain species to withstand environmental extremes. Its complexity and effectiveness make it a fascinating subject of study, with practical implications for industries and public health. While not all microorganisms form spores, those that do, particularly bacteria, demonstrate an extraordinary capacity to endure and thrive in the face of adversity. This knowledge not only deepens our understanding of microbial life but also equips us with tools to manage spore-related challenges effectively.

Can Spores Survive in Space? Exploring Microbial Life's Cosmic Resilience

You may want to see also

Fungal Spore Formation: Processes fungi use to produce spores for reproduction and dispersal

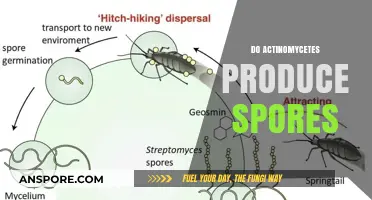

Not all microorganisms produce spores, but fungi have mastered this survival strategy. Unlike bacteria, which primarily rely on binary fission, fungi employ diverse mechanisms to generate spores, ensuring their persistence across harsh conditions and facilitating dispersal to new habitats. This process, known as sporulation, is a cornerstone of fungal life cycles, enabling them to thrive in diverse environments, from soil and decaying matter to human hosts.

Fungal spore formation is a complex, multi-step process involving specialized cellular structures and intricate signaling pathways. It begins with the differentiation of specific fungal cells, often triggered by environmental cues such as nutrient depletion, temperature changes, or population density. These cells then undergo a series of morphological changes, including nuclear division, cell wall modifications, and the accumulation of storage compounds, ultimately leading to the production of spores. For instance, in the model fungus *Aspergillus nidulans*, sporulation is regulated by the *brlA* gene, which activates a cascade of transcription factors, orchestrating the development of conidiospores, a type of asexual spore.

Consider the following steps in fungal spore formation, using *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker's yeast) as an example: (1) Induction: Nutrient limitation, particularly nitrogen depletion, triggers the initiation of sporulation. (2) Meiosis: Diploid cells undergo two rounds of nuclear division, producing four haploid nuclei. (3) Sporulation: Each nucleus becomes enclosed within a prospore membrane, forming a spore. (4) Maturation: Spores accumulate storage carbohydrates, such as trehalose, and modify their cell walls to enhance resistance to environmental stresses. This process typically takes 5-7 days under optimal conditions (e.g., 25°C, pH 5.5) and results in the production of 4-8 spores per cell.

A comparative analysis of fungal spore types reveals distinct strategies for survival and dispersal. Asexual spores, like conidia in *Aspergillus* or yeast cells in *Candida*, are produced rapidly and in large quantities, enabling quick colonization of new environments. In contrast, sexual spores, such as asci in *Neurospora* or basidiospores in mushrooms, are more resilient, often surviving extreme conditions like desiccation or freezing. For example, *Cryptococcus neoformans* produces melanized spores that can withstand temperatures as low as -80°C, while *Claviceps purpurea* spores remain viable in soil for over a decade.

To harness fungal sporulation in practical applications, consider these tips: (1) Laboratory Cultivation: Maintain cultures at 22-28°C and adjust pH to 5.0-6.0 for optimal sporulation. (2) Industrial Fermentation: Use sporulation-inducing media (e.g., 2% glucose, 1% peptone, 0.1% yeast extract) to maximize spore yield in biotechnological processes. (3) Disease Control: Target sporulation pathways in pathogenic fungi, such as inhibiting *brlA* homologs, to develop antifungal strategies. For instance, fludioxonil disrupts spore formation in *Botrytis cinerea*, reducing gray mold in crops.

In conclusion, fungal spore formation is a sophisticated, adaptable process that underpins fungal ecology and biotechnology. By understanding the mechanisms and diversity of sporulation, we can leverage this knowledge for applications ranging from food production to disease management, while also appreciating the resilience of fungi in the natural world.

Are Psilocybin Mushroom Spores Legal in the US?

You may want to see also

Non-Spore Forming Microbes: Microorganisms that lack spore-forming abilities and their survival strategies

Not all microorganisms possess the remarkable ability to form spores, a survival mechanism that allows certain bacteria and fungi to endure extreme conditions. This raises the question: how do non-spore-forming microbes persist in environments that would otherwise be inhospitable? These organisms, lacking the protective spore structure, have evolved a diverse array of strategies to ensure their survival and proliferation. Understanding these mechanisms not only sheds light on microbial resilience but also has practical implications for fields like food preservation, medicine, and environmental science.

One key survival strategy employed by non-spore-forming microbes is the formation of biofilms. Biofilms are complex communities of microorganisms encased in a self-produced extracellular matrix, often composed of polysaccharides, proteins, and DNA. This matrix provides a protective barrier against harsh conditions such as desiccation, antibiotics, and host immune responses. For instance, *Pseudomonas aeruginosa*, a common pathogen in hospital-acquired infections, thrives in biofilms on medical devices like catheters. To combat biofilm-related infections, clinicians often recommend antimicrobial lock therapy, where a high concentration (e.g., 70% ethanol or 10,000 IU/mL heparin) is instilled into the catheter to disrupt the biofilm matrix.

Another survival tactic is the production of resistant cell structures. Some non-spore-forming bacteria, like *Mycobacterium tuberculosis*, have cell walls rich in mycolic acids, which confer resistance to drying and chemical disinfectants. This adaptation allows them to persist in hostile environments, including the human body, where they can remain dormant for years. Similarly, certain yeasts, such as *Candida albicans*, can transition into a filamentous form, enhancing their ability to adhere to surfaces and evade immune detection. For individuals at risk of fungal infections, maintaining a balanced diet rich in probiotics (e.g., yogurt with live cultures) can help suppress opportunistic pathogens like *Candida*.

Non-spore-forming microbes also exploit metabolic flexibility to survive in nutrient-limited environments. For example, *Escherichia coli*, a common gut bacterium, can switch between aerobic and anaerobic respiration depending on oxygen availability. This adaptability allows it to thrive in diverse habitats, from the intestines to contaminated water sources. In food preservation, understanding this metabolic versatility is crucial; techniques like pasteurization (heating to 63°C for 30 minutes) effectively kill vegetative cells but must be combined with refrigeration to prevent residual bacteria from multiplying.

Finally, some non-spore-forming microbes rely on symbiotic relationships for survival. For instance, *Lactobacillus* species in the human gut produce lactic acid, which inhibits the growth of harmful bacteria while benefiting the host by aiding digestion. This mutualistic relationship highlights how microbes can thrive without spores by leveraging their environment and host interactions. To support beneficial gut flora, adults are advised to consume 10–20 billion CFUs (colony-forming units) of probiotics daily, particularly after antibiotic treatment.

In summary, non-spore-forming microbes employ a range of sophisticated strategies—from biofilm formation to metabolic adaptability—to survive and flourish in challenging environments. By studying these mechanisms, we gain insights into microbial ecology and develop more effective methods to control harmful pathogens while promoting beneficial microorganisms.

Understanding Isolated Spore Syringes: A Beginner's Guide to Mushroom Cultivation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Triggers for Sporulation: Factors like nutrient depletion or heat that induce spore formation

Not all microorganisms form spores, but those that do often respond to specific environmental cues. This process, known as sporulation, is a survival strategy employed by certain bacteria, fungi, and algae to endure harsh conditions. Understanding the triggers that initiate spore formation is crucial for fields like microbiology, food safety, and environmental science.

Nutrient depletion acts as a primary signal for many spore-forming organisms. When essential resources like carbon, nitrogen, or phosphorus become scarce, microorganisms like *Bacillus subtilis* and *Clostridium botulinum* initiate sporulation. This response is not merely a last-ditch effort but a highly regulated process. For instance, in *B. subtilis*, the depletion of amino acids triggers a signaling cascade involving the phosphorylation of the master regulator Spo0A, ultimately leading to the activation of sporulation genes. In practical terms, this means that controlling nutrient availability in food processing can prevent spore formation, reducing the risk of contamination by pathogens like *C. botulinum*.

Heat stress is another potent environmental trigger for sporulation, particularly in thermophilic bacteria such as *Geobacillus stearothermophilus*. Exposure to temperatures above their optimal growth range (e.g., 50–70°C) induces these organisms to form spores as a protective measure. This mechanism is exploited in sterilization processes, where heat-resistant spores serve as bioindicators. For example, in autoclave validation, the complete inactivation of *G. stearothermophilus* spores at 121°C for 15 minutes confirms effective sterilization. Conversely, understanding this trigger helps in designing more efficient pasteurization methods to eliminate spore-forming pathogens in dairy products without compromising quality.

Osmotic stress, caused by high salt or sugar concentrations, also induces sporulation in certain microorganisms. Halophilic bacteria like *Halobacterium salinarum* form spores in response to extreme salinity, while some fungi, such as *Aspergillus* species, sporulate under hypertonic conditions. This adaptation is particularly relevant in food preservation, where high-salt or high-sugar environments are used to inhibit microbial growth. However, spore formation under these conditions can lead to spoilage or health risks if not managed properly. For instance, honey’s low water activity prevents most microbial growth but can still support spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridium* if contaminated.

Finally, pH extremes and oxidative stress are less common but equally significant triggers for sporulation. Acidophilic bacteria like *Sulfolobus acidocaldarius* form spores in highly acidic environments, while some fungi sporulate under alkaline conditions. Oxidative stress, often caused by exposure to reactive oxygen species, induces sporulation in certain bacteria as a defense mechanism. These triggers highlight the versatility of sporulation as a survival strategy across diverse ecosystems. For researchers and industry professionals, identifying and manipulating these environmental factors can lead to advancements in biotechnology, such as enhancing spore production for probiotics or developing targeted antimicrobial strategies.

In summary, sporulation is not a random event but a response to specific environmental challenges. By understanding the triggers—nutrient depletion, heat, osmotic stress, pH extremes, and oxidative stress—we can better control spore formation in various contexts, from food safety to industrial processes. This knowledge not only aids in preventing contamination but also opens avenues for harnessing spores in beneficial applications.

Do All Bacteria Form Spores? Unraveling Microbial Survival Strategies

You may want to see also

Medical Significance of Spores: Role of microbial spores in infections, diseases, and antibiotic resistance

Not all microorganisms produce spores, but those that do pose unique challenges in medical settings. Spores are highly resistant structures that allow certain bacteria, fungi, and even some protozoa to survive extreme conditions—heat, desiccation, radiation, and antibiotics. This resilience enables them to persist in hospital environments, on medical equipment, and even within the human body, often leading to infections that are difficult to treat. For instance, *Clostridioides difficile* spores can survive on surfaces for months, causing recurrent infections in healthcare facilities, particularly among elderly patients or those on prolonged antibiotic therapy. Understanding spore-forming microorganisms is critical for infection control and treatment strategies.

Consider the role of spores in disease pathogenesis. When spores enter a favorable environment, such as the human gut, they germinate into active cells that can produce toxins or invade tissues. *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax, forms spores that can remain dormant in soil for decades before infecting humans or animals. Inhalation of just 8,000–50,000 spores can lead to fatal pulmonary anthrax if untreated. Similarly, *Clostridium tetani* spores, found in soil and animal feces, germinate in deep puncture wounds, producing tetanospasmin, a potent neurotoxin causing tetanus. These examples highlight how spores act as silent reservoirs of infection, requiring specific medical interventions.

Antibiotic resistance further complicates the management of spore-related infections. Spores themselves are inherently resistant to most antibiotics due to their impermeable outer layers and dormant metabolic state. Once germinated, the active cells may also harbor resistance genes, as seen in *C. difficile* strains resistant to fluoroquinolones and metronidazole. This dual resistance mechanism necessitates alternative treatments, such as fecal microbiota transplantation for *C. difficile* infections or high-dose penicillin for anthrax. Additionally, spore decontamination in healthcare settings relies on harsh disinfectants like chlorine bleach or hydrogen peroxide vapor, as standard cleaning methods often fail.

To mitigate the risks posed by microbial spores, healthcare providers must adopt targeted strategies. For at-risk populations, such as immunocompromised patients or those undergoing chemotherapy, prophylactic measures like vaccination (e.g., tetanus toxoid) or environmental spore control are essential. In outbreak scenarios, rapid identification of spore-forming pathogens through molecular diagnostics (e.g., PCR for *C. difficile* toxin genes) can guide appropriate treatment. Patients should be educated on infection risks, such as avoiding soil contamination of wounds and practicing proper hand hygiene in healthcare settings. By addressing spores at both the clinical and environmental levels, medical professionals can reduce the burden of spore-related diseases.

In conclusion, while not all microorganisms produce spores, those that do have a disproportionate impact on human health. Their ability to withstand extreme conditions, cause severe diseases, and resist antibiotics underscores their medical significance. From anthrax to *C. difficile* infections, spore-forming pathogens demand specialized prevention, diagnosis, and treatment approaches. By understanding their unique biology and implementing evidence-based practices, healthcare systems can better manage the challenges posed by these resilient microbial forms.

Mold Spores and Fatigue: Uncovering the Hidden Health Connection

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all microorganisms produce spores. Only certain types of bacteria, fungi, algae, and protozoa have the ability to form spores as a survival mechanism.

Spores serve as a protective, dormant state that allows microorganisms to survive harsh environmental conditions such as heat, cold, desiccation, and chemicals, ensuring long-term survival.

Spores are commonly produced by bacteria (e.g., Bacillus and Clostridium), fungi (e.g., molds and mushrooms), and some algae and protozoa, but not by viruses or most other microbes.

No, only a specific group of bacteria called endospore-forming bacteria, such as those in the genera Bacillus and Clostridium, have the ability to produce spores.

Some spores, such as those from certain bacteria (e.g., Clostridium botulinum) and fungi (e.g., Aspergillus), can be harmful if ingested or inhaled, but many spores are harmless or even beneficial in various ecosystems.