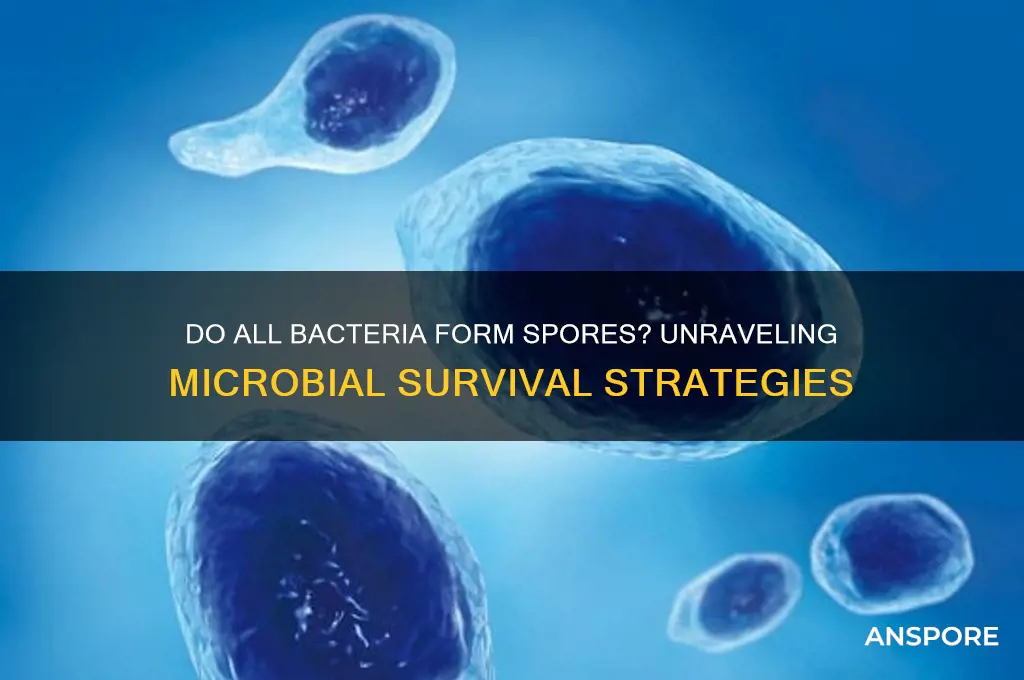

Not all bacteria are capable of forming spores. Sporulation is a specialized survival mechanism employed by certain bacterial species, primarily within the Firmicutes phylum, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*. These bacteria produce highly resistant endospores in response to harsh environmental conditions like nutrient depletion, desiccation, or extreme temperatures. Spores allow the bacteria to remain dormant for extended periods, ensuring their survival until more favorable conditions return. However, the majority of bacterial species lack this ability and rely on other strategies, such as biofilm formation or rapid reproduction, to endure adverse environments. Thus, while sporulation is a remarkable adaptation, it is not a universal trait among bacteria.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Are all bacteria spored? | No, not all bacteria form spores. |

| Bacteria that form spores | Primarily Gram-positive bacteria, including genera like Bacillus, Clostridium, Sporosarcina, and some Actinomycetes. |

| Purpose of spore formation | Survival in harsh conditions (e.g., heat, desiccation, radiation, chemicals). |

| Structure of bacterial spores | Highly resistant, dormant cells with thick, multilayered coats and minimal metabolic activity. |

| Bacteria that do not form spores | Most Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., Escherichia coli, Salmonella) and many Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., Staphylococcus, Streptococcus). |

| Sporulation process | Complex, energy-intensive process triggered by nutrient depletion or environmental stress. |

| Germination of spores | Spores revert to vegetative cells when conditions become favorable, resuming metabolic activity. |

| Significance of spores | Important in food spoilage, medical infections (e.g., Clostridium botulinum), and industrial applications (e.g., enzyme production). |

| Resistance of spores | Highly resistant to heat, UV radiation, desiccation, and disinfectants, making them difficult to eradicate. |

| Detection of spores | Specialized techniques like spore staining (e.g., Schaeffer-Fulton stain) and thermal resistance tests. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Endospore Formation: Some bacteria form endospores, resistant structures surviving harsh conditions, aiding in bacterial survival

- Exospore vs. Endospore: Exospores attach externally, while endospores form internally, differing in structure and function

- Non-Sporing Bacteria: Many bacteria lack spore-forming ability, relying on other mechanisms for survival and persistence

- Spore Germination: Spores activate under favorable conditions, resuming bacterial growth and metabolic activity

- Spore Resistance: Spores withstand extreme heat, radiation, and chemicals, ensuring bacterial longevity in adverse environments

Endospore Formation: Some bacteria form endospores, resistant structures surviving harsh conditions, aiding in bacterial survival

Not all bacteria form spores, but those that do employ a remarkable survival strategy: endospore formation. This process, unique to certain genera like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, involves the creation of highly resistant structures capable of withstanding extreme conditions such as heat, radiation, and desiccation. Endospores are not reproductive structures but rather dormant forms that allow bacteria to persist in environments where active growth is impossible. Unlike vegetative cells, which are vulnerable to environmental stressors, endospores can remain viable for years, even centuries, until conditions improve.

The formation of an endospore is a complex, multi-step process that begins with the replication of the bacterial genome and the assembly of a protective spore coat. Within the mother cell, a smaller cell, the forespore, develops and accumulates high levels of dipicolinic acid, a molecule that contributes to the spore’s heat resistance. The mother cell eventually lyses, releasing the mature endospore, which is encased in multiple layers, including a cortex rich in peptidoglycan and an outer exosporium. This layered structure provides unparalleled protection against physical and chemical insults, making endospores one of the most resilient life forms on Earth.

From a practical standpoint, understanding endospore formation is critical in fields like food safety and sterilization. For instance, *Clostridium botulinum* endospores can survive boiling temperatures, necessitating the use of high-pressure steam (autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes) to ensure their destruction. In healthcare, endospores of *Bacillus anthracis* pose a bioterrorism threat due to their stability and ease of dissemination. To mitigate risks, industries rely on spore-specific sterilization protocols, such as the use of hydrogen peroxide gas or gamma irradiation, which target the spore’s durable structure.

Comparatively, vegetative bacterial cells are far more susceptible to environmental challenges, often dying within minutes of exposure to heat or disinfectants. Endospores, however, require extreme measures for inactivation, underscoring their evolutionary advantage. This disparity highlights the importance of distinguishing between spored and non-spored bacteria in laboratory and industrial settings. For example, while ethanol (70%) effectively kills vegetative cells, it has no effect on endospores, which demand sporicidal agents like bleach (5% sodium hypochlorite) for decontamination.

In conclusion, endospore formation is a specialized adaptation that ensures bacterial survival in hostile environments. Its study not only deepens our understanding of microbial resilience but also informs practical strategies for controlling bacterial contamination. By recognizing the unique properties of endospores, we can develop more effective sterilization methods and safeguard public health. This knowledge bridges the gap between theoretical microbiology and real-world applications, demonstrating the profound impact of bacterial survival mechanisms on human activities.

Is Milky Spore Safe for Vegetable Gardens? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Exospore vs. Endospore: Exospores attach externally, while endospores form internally, differing in structure and function

Not all bacteria form spores, but those that do employ distinct strategies for survival. Among these, exospores and endospores represent two divergent adaptations, each with unique structural and functional characteristics. Exospores, less common and primarily observed in certain actinobacteria, form externally, often attached to the cell surface. This external attachment allows for rapid dispersal but offers limited protection compared to their internal counterparts. In contrast, endospores, found in genera like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, develop within the bacterial cell, providing unparalleled resistance to extreme conditions such as heat, radiation, and desiccation. This internal formation ensures a robust survival mechanism, albeit at the cost of slower release and dispersal.

Consider the process of endospore formation, a highly regulated and energy-intensive endeavor. It begins with the replication of the bacterial genome, followed by the engulfment of one copy within a developing spore. Layers of protective coatings, including a cortex rich in peptidoglycan and a proteinaceous coat, are then deposited. This intricate structure enables endospores to remain dormant for decades, only germinating when conditions become favorable. Exospores, on the other hand, lack this complexity, often consisting of a single protective layer, which limits their durability but facilitates quicker environmental adaptation.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these differences is crucial in fields like medicine and food safety. Endospores, due to their resilience, pose significant challenges in sterilization processes. For instance, autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes is typically required to destroy endospores, whereas exospores may succumb to less stringent conditions. In clinical settings, this distinction informs the selection of appropriate disinfection protocols, ensuring the elimination of spore-forming pathogens. Similarly, in the food industry, knowledge of spore types helps in designing preservation techniques, such as pasteurization or irradiation, tailored to the specific threats posed by exospores or endospores.

A comparative analysis reveals that while both exospores and endospores serve as survival mechanisms, their ecological roles differ markedly. Exospores, with their external attachment, are more suited to environments where rapid colonization is advantageous, such as nutrient-rich but unpredictable habitats. Endospores, however, excel in extreme and resource-scarce settings, acting as a long-term insurance policy for bacterial lineages. This divergence underscores the evolutionary ingenuity of bacteria, tailoring their spore strategies to specific environmental pressures.

In conclusion, the distinction between exospores and endospores highlights the diversity of bacterial survival mechanisms. While exospores prioritize quick dispersal and adaptability, endospores invest in unparalleled durability. Recognizing these differences not only advances our understanding of microbial ecology but also informs practical applications in sterilization, preservation, and pathogen control. Whether in a laboratory, hospital, or food processing plant, this knowledge equips us to combat spore-forming bacteria more effectively.

Understanding the Meaning of 'Spor' in Ancient Roman Culture and Language

You may want to see also

Non-Sporing Bacteria: Many bacteria lack spore-forming ability, relying on other mechanisms for survival and persistence

Not all bacteria form spores, and this distinction is crucial in understanding their survival strategies. While spore-forming bacteria, like *Clostridium botulinum* and *Bacillus anthracis*, can withstand extreme conditions by entering a dormant state, non-sporing bacteria rely on entirely different mechanisms to persist. These mechanisms are often tailored to their specific environments, whether it’s the human gut, soil, or aquatic systems. For instance, *Escherichia coli*, a common non-sporing bacterium, thrives by rapidly reproducing in nutrient-rich environments and forming biofilms to protect itself from antibiotics and host defenses. This adaptability highlights the diversity of bacterial survival strategies beyond spore formation.

One key survival mechanism for non-sporing bacteria is their ability to enter a viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state. In this state, bacteria reduce their metabolic activity to near-zero levels, making them undetectable by standard culturing methods. *Vibrio cholerae*, the causative agent of cholera, is known to adopt this strategy in response to nutrient deprivation or environmental stress. While VBNC bacteria are not actively dividing, they can revert to a culturable state when conditions improve, posing a potential health risk. Understanding this mechanism is essential for accurate detection and control, especially in water treatment and food safety protocols.

Another critical strategy for non-sporing bacteria is biofilm formation. Biofilms are structured communities of bacteria encased in a self-produced extracellular matrix, providing protection against antibiotics, host immune responses, and environmental stressors. *Pseudomonas aeruginosa*, a non-sporing pathogen commonly found in hospital settings, is notorious for its biofilm-forming ability, which contributes to its persistence in medical devices like catheters and ventilators. Disrupting biofilms often requires higher antibiotic dosages—up to 1,000 times the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)—or alternative treatments like enzymatic dispersal agents. Practical tips for preventing biofilm-related infections include regular cleaning of medical equipment and using antimicrobial coatings.

Non-sporing bacteria also exploit their genetic flexibility to survive. Unlike spore-formers, which rely on a fixed set of genes for dormancy, non-sporing bacteria can rapidly mutate or acquire new genes through horizontal gene transfer. *Helicobacter pylori*, a non-sporing bacterium associated with stomach ulcers, evades the immune system by altering its surface proteins, a process known as phase variation. This genetic adaptability allows it to persist in the hostile environment of the stomach for decades. For clinicians, this underscores the need for combination therapies, such as triple therapy (proton pump inhibitor, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin), to effectively treat infections caused by these bacteria.

Finally, some non-sporing bacteria survive by forming persistent cells, a small subpopulation that tolerates antibiotics without genetic resistance. *Mycobacterium tuberculosis*, the causative agent of tuberculosis, is a prime example. These persistent cells can remain dormant within macrophages, only to reactivate when conditions are favorable. This phenomenon complicates treatment, requiring prolonged antibiotic regimens (typically 6–9 months) to ensure complete eradication. For public health, this highlights the importance of adherence to treatment plans and the development of new drugs targeting persistent bacterial populations.

In summary, non-sporing bacteria employ a range of sophisticated mechanisms—from VBNC states and biofilms to genetic adaptability and persistent cells—to ensure their survival and persistence. Understanding these strategies is vital for developing effective control measures, whether in clinical, environmental, or industrial settings. While spore-forming bacteria grab attention for their resilience, non-sporing bacteria demonstrate that survival in the microbial world is far from one-size-fits-all.

Best Places to Purchase Morel Mushroom Spores for Cultivation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$430.79 $589.95

Spore Germination: Spores activate under favorable conditions, resuming bacterial growth and metabolic activity

Not all bacteria form spores, but those that do employ this strategy as a survival mechanism in harsh conditions. Spores are highly resistant structures that can endure extreme temperatures, desiccation, and chemical exposure. However, spore formation is not universal among bacteria; it is primarily observed in certain genera like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*. Understanding spore germination—the process by which spores activate and resume growth under favorable conditions—is crucial for fields like food safety, medicine, and environmental science.

Spore germination is a tightly regulated process triggered by specific environmental cues. These cues vary depending on the bacterial species but often include factors like nutrient availability, pH changes, and temperature shifts. For example, *Bacillus subtilis* spores germinate in response to nutrients like amino acids and sugars, while *Clostridium botulinum* spores require specific temperature ranges (25°C to 40°C) and the presence of certain chemicals. Once activated, the spore’s protective coat breaks down, allowing water and nutrients to enter, and metabolic activity resumes. This transition from dormancy to active growth is rapid, often occurring within minutes to hours under optimal conditions.

From a practical standpoint, controlling spore germination is essential in preventing bacterial contamination. In food preservation, for instance, understanding the conditions that trigger germination helps in designing effective sterilization processes. High-pressure processing (HPP) and thermal treatments (e.g., 121°C for 15 minutes) are commonly used to inactivate spores in canned foods. Similarly, in healthcare, knowing how spores like those of *Clostridioides difficile* germinate aids in developing targeted therapies to prevent infections. For example, antibiotics such as vancomycin and fidaxomicin are used to treat *C. difficile* infections by disrupting spore germination and outgrowth.

Comparatively, spore germination differs from vegetative bacterial growth in its resilience and activation requirements. While vegetative cells are more susceptible to environmental stressors, spores can remain dormant for years, waiting for the right conditions to germinate. This distinction highlights the evolutionary advantage of sporulation, enabling bacteria to survive in environments where non-spore-forming species would perish. However, this resilience also poses challenges, particularly in industries where complete sterilization is critical.

In conclusion, spore germination is a fascinating and complex process that bridges bacterial dormancy and active life. By understanding the specific triggers and mechanisms involved, we can better manage spore-forming bacteria in various contexts. Whether in food safety, medicine, or environmental management, controlling spore activation is key to preventing contamination and ensuring public health. Practical strategies, such as optimizing sterilization techniques and developing targeted antimicrobial agents, rely on this knowledge to combat spore-forming pathogens effectively.

Exploring the Microscopic World: What Do Spores Really Look Like?

You may want to see also

Spore Resistance: Spores withstand extreme heat, radiation, and chemicals, ensuring bacterial longevity in adverse environments

Not all bacteria form spores, but those that do possess an extraordinary survival mechanism. Spores are highly resistant structures that allow certain bacterial species to endure conditions that would be lethal to their vegetative forms. This resistance is a key factor in the longevity and persistence of bacteria in environments where other organisms cannot survive.

The Science of Spore Resistance

Spores achieve their remarkable durability through a combination of structural and biochemical adaptations. The spore coat, composed of layers of proteins and peptidoglycan, acts as a protective barrier against heat, desiccation, and chemicals. Additionally, the low water content and high concentration of calcium dipicolinate within spores minimize cellular damage from radiation and extreme temperatures. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores can withstand temperatures exceeding 100°C for hours, while *Clostridium botulinum* spores survive autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes—a standard sterilization method.

Practical Implications of Spore Resistance

Understanding spore resistance is critical in industries such as food safety, healthcare, and environmental management. In food processing, spores of *Clostridium perfringens* and *Bacillus cereus* can survive cooking temperatures, leading to foodborne illnesses if not eliminated through proper sterilization techniques. In healthcare, spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridioides difficile* pose challenges in hospital settings, as they resist common disinfectants such as alcohol-based hand sanitizers. To combat this, facilities must use sporicidal agents like chlorine bleach (5,000–10,000 ppm) or hydrogen peroxide (6–7%) for surface disinfection.

Comparative Analysis: Spores vs. Vegetative Cells

While vegetative bacterial cells are vulnerable to environmental stressors, spores can remain dormant for decades, waiting for favorable conditions to reactivate. This resilience is exemplified in extreme environments, such as the arid Atacama Desert or deep-sea hydrothermal vents, where spore-forming bacteria thrive despite harsh conditions. In contrast, non-spore-forming bacteria like *Escherichia coli* require nutrient-rich environments and are quickly inactivated by heat or disinfectants. This comparison highlights the evolutionary advantage of sporulation as a survival strategy.

Takeaway: Mitigating Spore Resistance

To effectively control spore-forming bacteria, targeted strategies are essential. For home use, boiling water for at least 10 minutes can inactivate most spores, while pressure cooking at 15 psi for 20 minutes ensures complete destruction. In industrial settings, combining heat treatment with chemical agents like formaldehyde or ethylene oxide is recommended for sterilization. Regular monitoring and validation of sterilization processes are crucial, especially in pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturing, to prevent contamination. By understanding and addressing spore resistance, we can minimize the risks associated with these resilient bacterial forms.

Understanding Bacterial Spores: Survival, Formation, and Significance Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all bacteria can form spores. Only certain types of bacteria, such as those in the genera *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, have the ability to produce spores as a survival mechanism.

Bacterial spores serve as a protective, dormant form that allows bacteria to survive harsh environmental conditions, such as extreme temperatures, lack of nutrients, or exposure to chemicals.

Yes, some spored bacteria, like *Clostridium botulinum* and *Clostridium difficile*, can cause serious infections in humans when their spores germinate and the bacteria become active.

Spored bacteria have the unique ability to form highly resistant spores, while non-spored bacteria lack this survival mechanism and are generally more susceptible to environmental stresses.