Archaea, a domain of single-celled microorganisms distinct from bacteria and eukaryotes, are known for their remarkable adaptability to extreme environments, such as hot springs, deep-sea hydrothermal vents, and highly saline habitats. While archaea share some similarities with bacteria, they possess unique cellular structures and metabolic pathways. One question that often arises is whether archaea produce spores, a survival mechanism commonly associated with bacteria and some fungi. Unlike bacteria, which form endospores to withstand harsh conditions, archaea do not produce spores. Instead, they rely on other strategies, such as robust cell walls, specialized membrane lipids, and unique metabolic adaptations, to survive in their extreme habitats. This distinction highlights the evolutionary divergence between archaea and bacteria, emphasizing the diverse ways in which microorganisms cope with environmental challenges.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do Archaea produce spores? | No, archaea do not produce spores. Sporulation is a process primarily associated with certain bacteria (e.g., Bacillus, Clostridium) and some eukaryotes (e.g., fungi), but not with archaea. |

| Reproduction in Archaea | Archaea reproduce asexually through binary fission, fragmentation, or budding, depending on the species. |

| Survival Mechanisms | Instead of spores, archaea have evolved other strategies to survive harsh conditions, such as forming cysts, biofilms, or producing protective molecules like extremozymes and compatible solutes. |

| Endospores vs. Archaea | Endospores, produced by some bacteria, are highly resistant structures, whereas archaea lack such structures and rely on their robust cell walls and membranes for survival in extreme environments. |

| Environmental Adaptation | Archaea are known for their ability to thrive in extreme environments (e.g., high temperatures, salinity, acidity) due to unique cellular adaptations, not spore formation. |

| Genetic Evidence | Genomic studies have not identified spore-related genes in archaea, further confirming their inability to produce spores. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Sporulation mechanisms in archaea

Archaea, often thriving in extreme environments, have evolved unique survival strategies. While sporulation is a well-known mechanism in bacteria, its occurrence in archaea has been a subject of scientific inquiry. Recent studies suggest that certain archaeal species, particularly those in the genus *Halobacterium*, exhibit sporulation-like processes, though distinct from bacterial spore formation. These structures, termed "cysts" or "resting cells," serve as protective states during adverse conditions, challenging the traditional view that archaea lack sporulation mechanisms.

Analyzing the sporulation-like process in *Halobacterium salinarum* provides insight into its adaptive strategies. When exposed to high salinity or desiccation, these archaea undergo cellular shrinkage, DNA condensation, and wall thickening, forming cysts. Unlike bacterial spores, these cysts retain metabolic activity at a reduced rate, allowing rapid revival upon environmental improvement. This mechanism highlights archaea’s ability to balance dormancy and readiness for reactivation, a critical trait for survival in fluctuating habitats.

For researchers studying archaeal sporulation, a step-by-step approach can elucidate these mechanisms. Begin by culturing *Halobacterium* under optimal conditions (37°C, 20% salinity). Induce sporulation by gradually increasing salinity to 30% or subjecting cultures to controlled desiccation. Monitor cellular changes using phase-contrast microscopy and DNA staining to observe condensation. Revive cysts by returning them to optimal conditions and measure metabolic recovery rates. Caution: Avoid abrupt environmental shifts, as they may damage cells irreversibly.

Comparatively, archaeal cysts differ from bacterial spores in key aspects. Bacterial spores are metabolically dormant, with DNA protected by a thick protein coat, while archaeal cysts maintain low metabolic activity and lack a distinct spore coat. This distinction suggests convergent evolution of dormancy mechanisms rather than a shared ancestral trait. Understanding these differences is crucial for biotechnological applications, such as using archaeal cysts for bio preservation in extreme conditions.

In practical terms, archaeal sporulation mechanisms offer potential for industrial and environmental applications. For instance, cyst-forming archaea could be employed in bioremediation of hypersaline or arid environments, where their resilience ensures survival during cleanup processes. Additionally, studying these mechanisms may inspire synthetic biology approaches to engineer robust microbial systems. Researchers should focus on identifying genetic regulators of cyst formation, such as those involved in DNA condensation and cell wall modification, to harness this potential effectively.

Are Spores an Aerosol? Exploring the Science Behind Airborne Particles

You may want to see also

Environmental triggers for archaeal spore formation

Archaea, often thriving in extreme environments, have long fascinated scientists with their resilience. While not all archaea produce spores, certain species within the phylum Euryarchaeota, particularly those in the class Halobacteria, are known to form structures akin to bacterial endospores. These spore-like structures, termed "cysts," serve as survival mechanisms in harsh conditions. Understanding the environmental triggers for archaeal spore formation is crucial for unraveling their adaptive strategies and potential biotechnological applications.

Identifying Key Triggers:

Archaeal spore formation is primarily induced by environmental stressors that threaten cellular integrity. One of the most potent triggers is desiccation, a common challenge in hypersaline habitats where halophilic archaea reside. Studies show that water activity levels below 0.75 (measured as aw) consistently initiate cyst formation in species like *Halobacterium salinarum*. Another critical factor is nutrient deprivation, particularly the depletion of phosphorus and nitrogen, which signals cells to enter a dormant state. For instance, reducing phosphate concentrations to below 10 μM in growth media has been observed to accelerate spore-like structure development in *Haloarcula* species.

Comparative Analysis of Stressors:

While desiccation and nutrient limitation are well-documented triggers, other stressors exhibit varying efficacy. High UV radiation, a common challenge in surface-dwelling archaea, induces DNA damage but does not consistently trigger spore formation unless coupled with other stressors. In contrast, temperature extremes (above 50°C or below 4°C) can stimulate cyst formation in some species, though the response is highly strain-specific. For example, *Natronomonas pharaonis* forms cysts at temperatures exceeding 55°C, whereas *Halorubrum lacusprofundi* responds more robustly to freezing conditions.

Practical Implications and Experimental Tips:

For researchers studying archaeal spore formation, controlling environmental parameters is essential. To induce cysts in halophilic archaea, gradually reduce water activity using polyethylene glycol (PEG) solutions or increase salt concentrations to mimic desiccation. Nutrient limitation experiments should involve replacing standard media with minimal media lacking key elements like phosphate or ammonium. When testing temperature effects, use gradient incubators to avoid thermal shock, which can confound results. Additionally, monitor cellular responses using phase-contrast microscopy to track morphological changes indicative of spore formation.

Takeaway and Future Directions:

Mold Spores: Are They Truly Everywhere in Our Environment?

You may want to see also

Types of spores produced by archaea

Archaea, often thriving in extreme environments, have evolved unique survival strategies. Unlike bacteria, which commonly produce endospores, archaea primarily form cyst-like structures or resting cells as their spore equivalents. These structures are not true spores in the bacterial sense but serve similar functions, enabling archaea to endure harsh conditions such as desiccation, high salinity, or extreme temperatures. For instance, *Halobacterium salinarum* forms cysts in response to nutrient deprivation, showcasing archaea’s adaptability.

To understand the types of spore-like structures archaea produce, consider their environmental niches. Thermophilic archaea, such as those in the genus *Sulfolobus*, form resting cells when exposed to heat stress or pH fluctuations. These cells have thickened cell walls and reduced metabolic activity, allowing them to persist until conditions improve. Unlike bacterial endospores, these resting cells retain their cellular integrity without undergoing a complete metabolic shutdown, making them a distinct survival mechanism.

Another notable example is halophilic archaea, which produce cysts in response to osmotic stress. These cysts are characterized by a condensed cytoplasm and a protective outer layer that minimizes water loss. For practical purposes, researchers studying archaea in hypersaline environments often induce cyst formation by gradually increasing salt concentrations, observing the transition from active cells to dormant states. This process highlights the dynamic nature of archaeal survival strategies.

Comparatively, psychrophilic archaea in cold environments, such as those in the genus *Methanogenium*, form spore-like structures that resist freezing temperatures. These structures are less studied but are believed to involve membrane alterations and protein stabilization to maintain cellular function. While not as robust as bacterial endospores, these adaptations underscore archaea’s ability to thrive in extreme cold, where other organisms cannot survive.

In summary, archaea produce diverse spore-like structures tailored to their specific environments. From thermophilic resting cells to halophilic cysts and psychrophilic adaptations, these mechanisms demonstrate archaea’s evolutionary ingenuity. Understanding these structures not only sheds light on archaeal biology but also has practical applications in biotechnology, such as developing extremophile-inspired preservation techniques. For enthusiasts and researchers alike, studying these spore-like forms offers a window into the resilience of life’s earliest forms.

Are All Gram-Positive Bacteria Non-Spore Forming? Unraveling the Myth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of spores in archaeal survival

Archaea, often thriving in extreme environments, face challenges that demand robust survival strategies. While not all archaea produce spores, those that do leverage this mechanism to endure harsh conditions such as desiccation, radiation, and temperature extremes. Spores are dormant, highly resistant structures that safeguard the organism’s genetic material until conditions improve. For example, *Halobacterium salinarum*, an archaeon found in salt flats, forms spore-like structures to survive prolonged salt stress. This ability underscores the evolutionary advantage of sporulation in archaeal survival.

To understand the role of spores, consider the step-by-step process of spore formation in archaea. First, the cell undergoes metabolic changes, accumulating protective molecules like trehalose and proteins that stabilize DNA. Next, the cell wall thickens, creating a barrier against external stressors. Finally, the cell enters a dormant state, minimizing energy consumption. This process is akin to hibernation, allowing archaea to persist in environments where active growth is impossible. For instance, in hot springs, *Thermococcus* species form spores to withstand sudden temperature fluctuations, ensuring long-term survival.

Comparatively, archaeal spores differ from bacterial endospores in structure and composition. While bacterial spores have a thick protein coat, archaeal spores often rely on unique lipids and polysaccharides tailored to their habitats. This distinction highlights archaea’s adaptability to extreme niches. For practical application, researchers studying archaeal spores in Martian-like conditions have found that these structures can survive radiation doses up to 500 Gy, far exceeding what most life forms can tolerate. This resilience makes archaeal spores valuable models for astrobiology and biotechnology.

Persuasively, the study of archaeal spores offers more than academic curiosity—it has tangible benefits. Understanding spore formation could inspire new preservation techniques for vaccines or food in arid regions. For instance, mimicking archaeal spore mechanisms might lead to stabilizers that protect biologics at room temperature, reducing reliance on cold chains. Additionally, archaeal spores’ resistance to radiation could inform strategies for protecting crops in space agriculture. By harnessing these natural strategies, we can address real-world challenges in medicine, agriculture, and space exploration.

Descriptively, imagine a hypersaline lake where sunlight blazes and salt crystals encrust the shore. Here, archaea like *Haloarcula* form spores that glimmer like microscopic pearls, each a testament to life’s tenacity. These spores remain dormant for years, waiting for rain to dilute the salinity and revive them. This vivid example illustrates how spores serve as archaea’s time capsules, preserving life in environments that oscillate between inhospitable and habitable. Such adaptations remind us of the ingenuity embedded in microbial survival strategies.

Mushroom Spores and Allergies: Uncovering the Hidden Triggers and Symptoms

You may want to see also

Comparing archaeal and bacterial spore production

Archaea and bacteria, both members of the prokaryotic domain, have evolved distinct survival strategies in response to harsh environmental conditions. While bacterial spore formation is well-documented, the question of whether archaea produce spores remains a topic of scientific inquiry. Unlike bacteria, which form highly resistant endospores, archaea are known to produce structures like cysts or dormant cells, but these are not equivalent to bacterial spores in terms of resilience or structure. This fundamental difference highlights the unique adaptations of archaea to extreme environments, such as high salinity, temperature, and pH, where bacterial spores might not thrive.

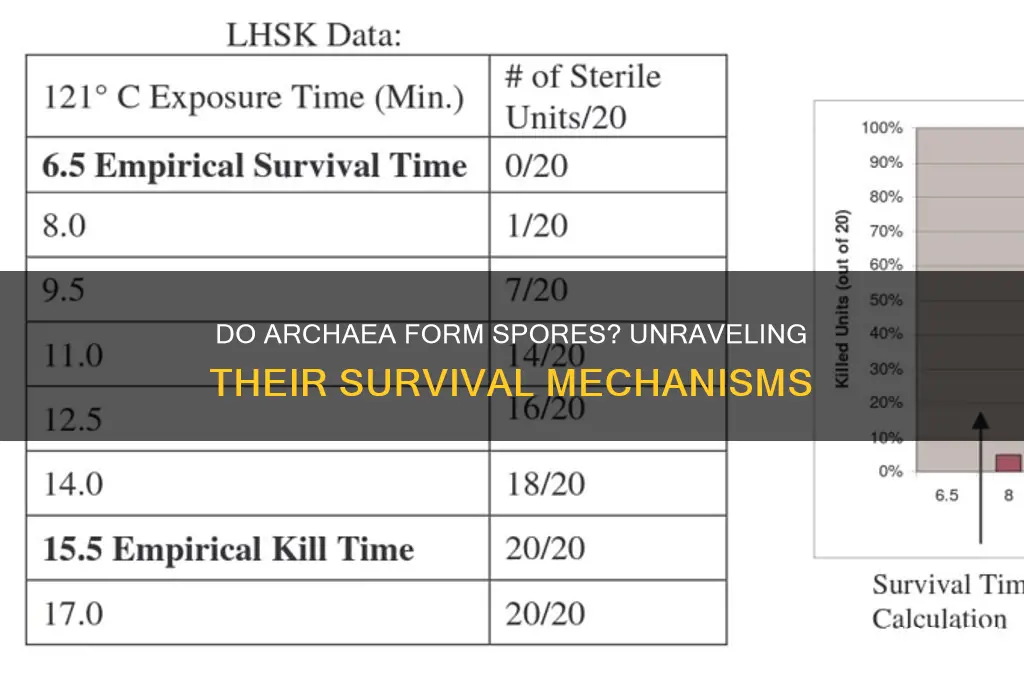

To compare archaeal and bacterial spore production, consider the mechanisms involved. Bacterial spores, such as those formed by *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, undergo a complex process of sporulation, involving the formation of a thick protein coat and multiple layers that protect the DNA. Archaea, on the other hand, lack this elaborate process. Instead, some archaea, like *Halobacterium*, form cyst-like structures through changes in cell wall composition and metabolism. These structures are less durable than bacterial spores but suffice for survival in their specific niches. For instance, while bacterial spores can withstand autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes, archaeal cysts are typically viable only under the extreme conditions they are adapted to, such as hypersaline lakes.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these differences is crucial for industries like biotechnology and astrobiology. Bacterial spores are often targeted in sterilization processes, requiring specific protocols to ensure their eradication. Archaeal dormant forms, however, may not be affected by standard sterilization methods, posing challenges in environments like food processing or pharmaceutical manufacturing. For example, archaea in salted food products might survive typical pasteurization, necessitating alternative preservation techniques, such as high-pressure processing or specific antimicrobial agents.

A persuasive argument can be made for further research into archaeal dormancy mechanisms. While bacterial spore biology has been extensively studied, archaeal strategies remain understudied, despite their potential applications. Archaeal resilience could inspire new biomolecules or preservation methods for extreme conditions, such as space travel or deep-sea exploration. For instance, enzymes from archaea like *Thermococcus* are already used in PCR due to their thermostability, and understanding their dormant forms could unlock similar innovations.

In conclusion, while archaea do not produce spores in the bacterial sense, their unique dormant structures reflect specialized adaptations to extreme environments. Comparing these mechanisms reveals not only evolutionary divergence but also practical implications for industries and research. By studying archaeal dormancy, scientists can bridge gaps in our understanding of microbial survival and harness these adaptations for technological advancements. This comparison underscores the importance of exploring less-studied organisms to uncover novel solutions to age-old challenges.

Effective Methods to Eliminate Fungal Spores and Prevent Growth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, archaea do not produce spores. Sporulation is a process primarily associated with certain bacteria and fungi, not archaea.

While archaea do not form true spores, some species can enter dormant states or produce cyst-like structures under harsh conditions, though these are not equivalent to bacterial or fungal spores.

Archaea have evolved unique adaptations, such as specialized cell membranes and proteins, to survive extreme conditions, eliminating the need for spore formation as a survival strategy.