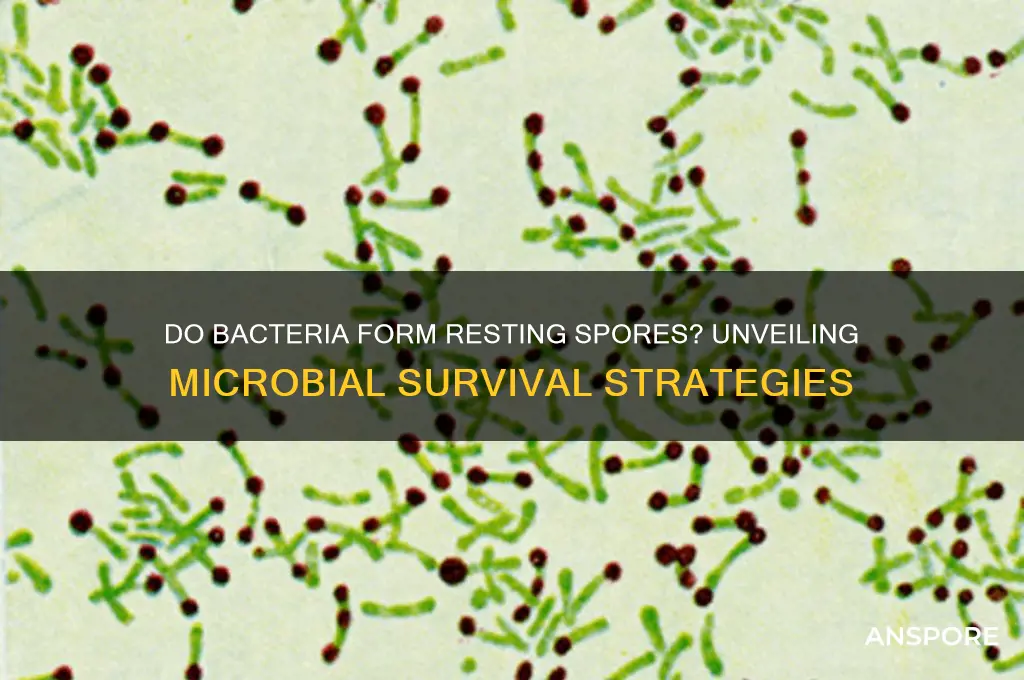

Bacteria, known for their remarkable adaptability and survival strategies, employ various mechanisms to endure harsh environmental conditions. One such strategy is the production of resting spores, a dormant form that allows them to withstand extreme temperatures, desiccation, and nutrient deprivation. Unlike vegetative cells, which are metabolically active, resting spores are highly resistant and can remain viable for extended periods, sometimes even centuries. This ability is particularly crucial for bacterial survival in unpredictable or hostile environments, ensuring their persistence until conditions become favorable again. While not all bacteria produce resting spores, those that do, such as species in the genera *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, highlight the evolutionary sophistication of microbial life. Understanding the formation and function of resting spores not only sheds light on bacterial resilience but also has significant implications in fields like food safety, medicine, and astrobiology.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Production of Resting Spores | Some bacteria produce resting spores, also known as endospores, as a survival mechanism. |

| Bacterial Groups | Primarily produced by Gram-positive bacteria, notably in the genus Bacillus and Clostridium. |

| Function | Serve as a dormant, highly resistant form to withstand harsh environmental conditions (e.g., heat, desiccation, chemicals). |

| Structure | Consist of a core cell containing DNA, surrounded by a cortex, spore coat, and sometimes an exosporium. |

| Resistance | Highly resistant to radiation, extreme temperatures, and most disinfectants. |

| Germination | Can remain viable for years or even centuries; germinate into vegetative cells under favorable conditions. |

| Significance | Important in food spoilage, medical infections (e.g., Clostridium botulinum), and environmental survival. |

| Examples | Bacillus anthracis (causes anthrax), Clostridium difficile (causes antibiotic-associated diarrhea). |

| Detection | Detected through spore staining techniques (e.g., Schaeffer-Fulton stain) and heat resistance tests. |

| Applications | Used in biotechnology for enzyme production and as probiotics in spore form. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Process: How and why bacteria form spores under stress conditions

- Types of Spores: Differentiating between endospores, cysts, and other bacterial resting forms

- Survival Mechanisms: Spores' resistance to heat, radiation, and desiccation for long-term survival

- Germination Triggers: Environmental cues that activate spore germination and return to vegetative growth

- Ecological Role: Spores' significance in bacterial persistence, dispersal, and ecosystem dynamics

Sporulation Process: How and why bacteria form spores under stress conditions

Bacteria, when faced with adverse environmental conditions such as nutrient depletion, extreme temperatures, or desiccation, initiate a survival mechanism known as sporulation. This process transforms a vegetative bacterial cell into a highly resilient spore, capable of enduring conditions that would otherwise be lethal. The sporulation process is a complex, multi-step transformation that involves significant morphological and biochemical changes. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis*, a well-studied bacterium, undergoes sporulation when starved of nutrients, forming spores that can survive for decades in a dormant state.

The sporulation process begins with an asymmetric cell division, where the bacterial cell divides into a larger mother cell and a smaller forespore. This division is regulated by a series of signaling pathways that detect environmental stress. The forespore then undergoes a series of maturation steps, including the synthesis of a thick, protective spore coat and the dehydration of the cytoplasm. This coat, composed of multiple layers of proteins and peptides, acts as a barrier against heat, radiation, and chemicals. For example, spores of *Clostridium botulinum* can survive boiling temperatures for several minutes, highlighting the effectiveness of this protective structure.

One of the most critical aspects of sporulation is the formation of dipicolinic acid (DPA), a molecule that binds calcium ions and contributes to the spore’s heat resistance. DPA levels in mature spores can reach up to 10-25% of the spore’s dry weight, playing a key role in stabilizing the spore’s DNA and proteins. This biochemical adaptation is essential for long-term survival, as demonstrated by spores of *Bacillus anthracis*, which can remain viable in soil for decades. Understanding this process has practical implications, such as in food preservation, where sporulation of pathogens like *Clostridium perfringens* poses significant challenges.

From a practical standpoint, preventing bacterial sporulation is crucial in industries like food production and healthcare. For instance, maintaining temperatures above 121°C for at least 15 minutes during sterilization processes (autoclaving) ensures the destruction of even the most resilient spores. Additionally, controlling nutrient availability and pH levels in food products can inhibit sporulation, reducing the risk of contamination. For example, acidic conditions (pH < 4.5) prevent spore germination in canned foods, a principle widely applied in the food industry.

In conclusion, the sporulation process is a remarkable bacterial survival strategy, driven by environmental stress and characterized by intricate cellular and biochemical changes. By forming spores, bacteria ensure their persistence in harsh conditions, posing challenges in various fields. However, understanding this process enables the development of effective strategies to control and eliminate spores, safeguarding health and industry. Whether in a laboratory or a factory, recognizing the mechanisms of sporulation is key to mitigating its impact.

Unlocking Rogue and Epic Modes in Spore: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Types of Spores: Differentiating between endospores, cysts, and other bacterial resting forms

Bacteria have evolved various survival strategies, and one of the most fascinating is their ability to produce resting forms, which allow them to endure harsh conditions. Among these, endospores, cysts, and other resting structures stand out, each with unique characteristics and functions. Understanding these differences is crucial for fields like microbiology, medicine, and environmental science.

Endospores, primarily produced by Gram-positive bacteria such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are highly resistant structures formed within the bacterial cell. They are not true spores but rather a dormant, tough coat that protects the bacterial DNA and a portion of the cytoplasm. Endospores can withstand extreme temperatures, radiation, and chemicals, making them nearly indestructible. For instance, *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax, forms endospores that can survive in soil for decades. To kill endospores, autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes is required, as standard disinfection methods often fail. This resilience makes endospores a critical concern in sterilization protocols, especially in healthcare and food industries.

Cysts, on the other hand, are resting forms produced by some protozoa and certain bacteria, such as *Azotobacter*. Unlike endospores, cysts are not as resistant to extreme conditions but serve as protective shells during unfavorable environments, such as nutrient depletion or desiccation. For example, *Giardia lamblia*, a protozoan parasite, forms cysts that can survive outside a host for weeks in water. Cysts are generally larger than endospores and contain a single cell encased in a protective wall. While they are less durable than endospores, cysts are still challenging to eliminate, often requiring specific disinfectants like chlorine or iodine. Understanding cyst formation is vital for water treatment and preventing waterborne diseases.

Other bacterial resting forms include exospores and budding cells. Exospores, produced by some Gram-negative bacteria like *Streptomyces*, are formed externally to the cell and are less resistant than endospores. Budding cells, seen in yeast-like bacteria such as *Blastococcus*, involve the formation of smaller cells that detach from the parent cell. These forms are less common but highlight the diversity of bacterial survival strategies. For instance, *Streptomyces* exospores are crucial in soil ecosystems, contributing to nutrient cycling and antibiotic production.

In practical terms, differentiating between these resting forms is essential for effective control measures. Endospores require extreme conditions for eradication, while cysts and other forms may be more susceptible to targeted treatments. For example, in a laboratory setting, a researcher might use heat shock to activate endospores before studying their germination, whereas cysts might be treated with specific chemicals to induce reactivation. Knowing the type of resting form can also guide public health interventions, such as ensuring water treatment plants use methods effective against cysts.

In summary, while all these structures serve as bacterial resting forms, their formation, resistance, and ecological roles differ significantly. Endospores are the most resilient, cysts are intermediate in durability, and other forms like exospores and budding cells are less common but equally important. Recognizing these distinctions is key to addressing challenges in sterilization, disease prevention, and environmental management. Whether in a clinical lab or a water treatment facility, this knowledge ensures targeted and effective strategies against bacterial survival mechanisms.

Can You Kill Mold Spores? Effective Methods and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Survival Mechanisms: Spores' resistance to heat, radiation, and desiccation for long-term survival

Bacteria, under adverse conditions, can transform into highly resilient structures known as spores. These spores are not merely dormant cells but are specifically engineered to withstand extreme environmental challenges. Among the most remarkable survival mechanisms of spores are their resistance to heat, radiation, and desiccation, enabling them to persist for centuries in environments that would destroy most life forms.

Consider the heat resistance of bacterial spores, particularly those from species like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*. These spores can survive temperatures exceeding 100°C, far beyond the boiling point of water. This resistance is attributed to their unique structure, including a thick protein coat and a dehydrated core that minimizes thermal damage. For instance, pasteurization at 72°C for 15 seconds is insufficient to kill spores, necessitating more extreme methods like autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes. This underscores the importance of precise temperature control in sterilization processes, especially in food preservation and medical settings.

Radiation resistance in spores is equally impressive. Spores can endure doses of ionizing radiation that would be lethal to vegetative cells. For example, *Deinococcus radiodurans* spores can survive exposure to thousands of Grays (Gy) of radiation, compared to the 5–10 Gy typically fatal to humans. This resistance stems from efficient DNA repair mechanisms and the spore’s compact, protected genetic material. Such resilience has implications for both astrobiology, where spores could potentially survive interplanetary travel, and biotechnology, where spores are studied for radiation-resistant genetic engineering.

Desiccation, or extreme drying, poses another challenge that spores overcome with ease. Spores can remain viable in dry conditions for decades, even centuries, by reducing their water content to as low as 1–2% of their dry weight. This desiccation tolerance is facilitated by the accumulation of protective molecules like dipicolinic acid, which stabilizes the spore’s structure. Practical applications of this resistance are seen in the long-term storage of bacterial cultures and the persistence of pathogens in arid environments, such as *Bacillus anthracis* in soil.

Understanding these survival mechanisms is not just an academic exercise; it has practical implications for industries ranging from healthcare to space exploration. For instance, hospitals must employ rigorous sterilization protocols to ensure spores are eradicated from medical equipment. Conversely, the study of spore resistance informs the development of extremophile-based technologies, such as radiation-resistant materials for space missions. By unraveling the secrets of spore survival, we gain insights into both the limits of life and the potential for its endurance in the harshest conditions.

Mushroom Spores and Respiratory Health: Potential Risks Explained

You may want to see also

Germination Triggers: Environmental cues that activate spore germination and return to vegetative growth

Bacteria, particularly species like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, produce resting spores as a survival strategy in harsh conditions. These spores remain dormant until specific environmental cues trigger germination, allowing them to revert to vegetative growth. Understanding these germination triggers is crucial for fields like food safety, medicine, and environmental science, as they dictate when and where bacterial populations can re-emerge.

Analytical Perspective:

Germination triggers are highly specific and often species-dependent. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores require a combination of nutrients (e.g., amino acids like L-valine or L-alanine) and warm temperatures (around 37°C) to initiate germination. In contrast, *Clostridium botulinum* spores respond to specific sugars and pH levels, typically in anaerobic environments. These cues mimic conditions favorable for growth, signaling to the spore that resources are available. Research shows that the concentration of triggers matters—for example, L-alanine must reach a threshold of 50–100 mM to effectively activate *Bacillus* spores. This specificity ensures spores remain dormant until conditions are truly optimal, maximizing survival chances.

Instructive Approach:

To control spore germination in practical settings, such as food preservation or medical sterilization, focus on manipulating environmental factors. For food safety, maintain low temperatures (below 4°C) and avoid cross-contamination with nutrient-rich substances. In laboratory settings, use nutrient-depleted media to keep spores dormant. Conversely, to activate spores for research, prepare a germination medium with specific triggers like 100 mM L-alanine and incubate at 37°C for 1–2 hours. Always monitor pH levels, as deviations from neutrality (pH 7) can inhibit or accelerate germination depending on the species.

Comparative Insight:

Unlike bacterial spores, fungal spores often require light or moisture as primary triggers. For example, *Aspergillus* spores germinate in the presence of water and oxygen, while bacterial spores prioritize nutrient availability. This difference highlights the evolutionary adaptation of bacteria to survive in nutrient-scarce environments. Additionally, bacterial spores are more resistant to extreme conditions, such as desiccation and radiation, making their germination triggers more complex and tightly regulated. Understanding these distinctions helps tailor strategies for controlling microbial growth in diverse contexts.

Descriptive Example:

Imagine a soil environment after a drought. As rain reintroduces moisture and organic matter, *Bacillus* spores detect nutrients like glucose and amino acids. Within hours, their coats rupture, and metabolic activity resumes. This process is not instantaneous—it involves a series of biochemical steps, including the activation of enzymes like germinant receptors and cortex-lytic enzymes. The spore’s return to vegetative growth is a testament to its resilience, transforming from a dormant, resilient structure into an active, replicating cell.

Persuasive Takeaway:

Mastering germination triggers is not just academic—it has real-world implications. In healthcare, understanding how *Clostridioides difficile* spores activate in the gut can lead to better treatments for antibiotic-associated diarrhea. In agriculture, controlling spore germination in soil can reduce crop contamination. By manipulating these cues, we can either prevent unwanted bacterial growth or harness it for biotechnological applications. The key lies in recognizing that spores are not passive entities but responsive survivors, waiting for the right moment to thrive.

Can Breathing Mold Spores Be Fatal? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Ecological Role: Spores' significance in bacterial persistence, dispersal, and ecosystem dynamics

Bacteria, often perceived as simple unicellular organisms, exhibit remarkable strategies for survival, and one of their most intriguing adaptations is the production of resting spores. These spores are not merely dormant forms but are dynamic entities that play a pivotal role in bacterial persistence, dispersal, and ecosystem dynamics. Understanding their ecological significance reveals how bacteria thrive in diverse and often harsh environments.

Consider the soil microbiome, a bustling ecosystem where bacterial spores act as time capsules. When conditions become unfavorable—such as drought, extreme temperatures, or nutrient scarcity—spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* enter a state of dormancy. These spores can remain viable for decades, even centuries, waiting for optimal conditions to reactivate. This persistence ensures that bacterial populations endure environmental fluctuations, maintaining ecosystem stability. For instance, in agricultural systems, spore-forming bacteria contribute to soil health by cycling nutrients and degrading organic matter, even during periods of stress.

Dispersal is another critical function of bacterial spores. Unlike vegetative cells, spores are highly resistant to physical and chemical stresses, allowing them to travel vast distances via wind, water, or animal vectors. This dispersal mechanism enables bacteria to colonize new habitats, from the depths of the ocean to the surfaces of plants. For example, *Bacillus thuringiensis* spores, known for their insecticidal properties, are widely dispersed in agricultural fields, where they protect crops by targeting pests. This natural biocontrol highlights how spores contribute to ecosystem balance and human food security.

The ecological dynamics of bacterial spores extend beyond persistence and dispersal; they also influence community structure and function. Spores act as a reservoir of genetic diversity, ensuring that bacterial populations can adapt to changing environments. In disturbed ecosystems, such as those affected by pollution or climate change, spore-forming bacteria often dominate, driving recovery processes. For instance, in oil-contaminated soils, *Bacillus* spores germinate and degrade hydrocarbons, facilitating remediation. This resilience underscores the role of spores in maintaining ecosystem services, from nutrient cycling to pollutant breakdown.

To harness the ecological potential of bacterial spores, practical strategies can be employed. In agriculture, incorporating spore-forming bacteria into biofertilizers enhances soil fertility and plant health. For environmental restoration, spore-based bioremediation agents can be applied to accelerate the cleanup of contaminated sites. However, caution is necessary; while most spore-forming bacteria are benign, some, like *Clostridium botulinum*, pose health risks. Proper identification and handling are essential to maximize benefits while minimizing hazards.

In summary, bacterial spores are not just survival mechanisms but key drivers of ecological processes. Their ability to persist, disperse, and shape ecosystem dynamics underscores their significance in both natural and managed environments. By understanding and leveraging these traits, we can foster sustainable practices that benefit ecosystems and human endeavors alike.

Alcohol's Effectiveness Against Bacteria Spores: Fact or Fiction?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all bacteria produce resting spores. Only certain bacterial species, such as those in the genera *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are known to form resting spores as a survival mechanism.

Bacterial resting spores serve as a protective, dormant form that allows bacteria to survive harsh environmental conditions, such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, or lack of nutrients, until more favorable conditions return.

Bacteria form resting spores through a process called sporulation, where a single cell undergoes a series of morphological and biochemical changes to produce a highly resistant spore within a protective outer layer.

Bacterial resting spores are extremely resistant to many common disinfection methods, including heat, chemicals, and radiation. Specialized treatments, such as autoclaving at high temperatures and pressures, are often required to destroy them.