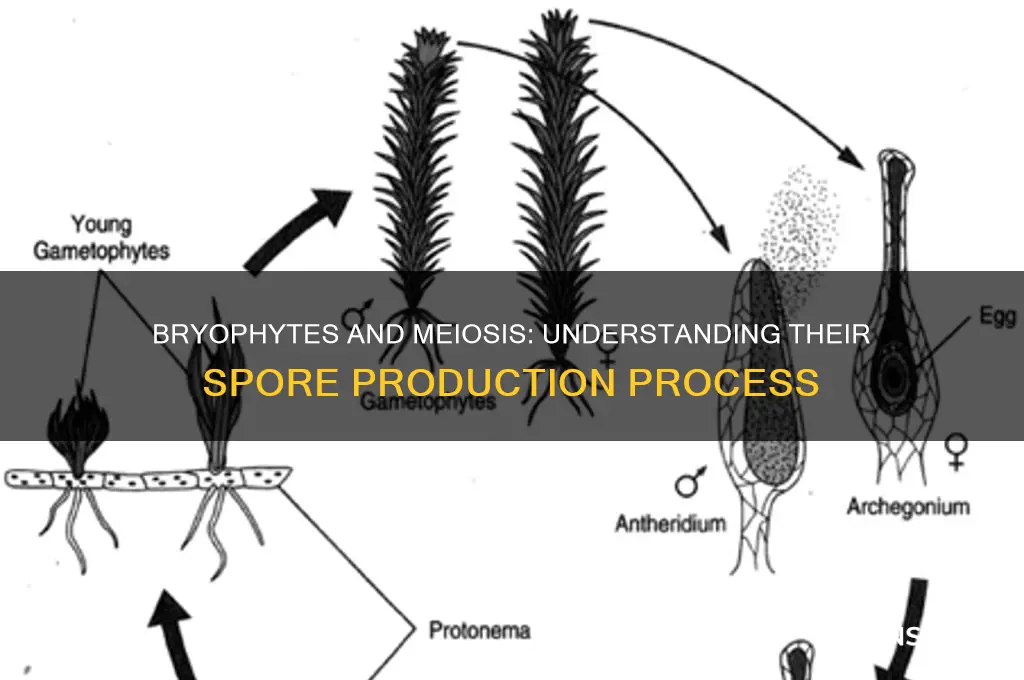

Bryophytes, a diverse group of non-vascular plants that includes mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, reproduce through a unique life cycle that alternates between a gametophyte and a sporophyte generation. A key aspect of their reproductive strategy is the production of spores, which are crucial for dispersal and survival. These spores are indeed produced through the process of meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in haploid cells. In bryophytes, meiosis occurs within the sporangium, a structure located on the sporophyte, leading to the formation of spores that can develop into new gametophytes. This meiotic process ensures genetic diversity and is fundamental to the life cycle of bryophytes, distinguishing them from more complex vascular plants.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spores Production Method | Bryophytes produce spores through meiosis. |

| Life Cycle Stage | Spores are produced in the sporophyte generation of the life cycle. |

| Type of Meiosis | Meiosis occurs in the sporangia, resulting in haploid spores. |

| Sporophyte Dependency | The sporophyte phase is dependent on the gametophyte for nutrition. |

| Spore Function | Spores serve as the dispersal and reproductive units in bryophytes. |

| Gametophyte Dominance | The gametophyte generation is dominant and long-lived in bryophytes. |

| Spore Germination | Spores germinate into protonema, which develops into the gametophyte. |

| Taxonomic Groups | Applies to all bryophytes, including mosses, liverworts, and hornworts. |

| Chromosome Number | Spores are haploid (n), while the sporophyte is diploid (2n). |

| Reproductive Strategy | Alternation of generations with meiosis ensuring genetic diversity. |

Explore related products

$18.49 $24.95

What You'll Learn

Meiosis in Bryophyte Life Cycle

Bryophytes, a group of non-vascular plants including mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, exhibit a life cycle that alternates between a gametophyte and a sporophyte generation. Central to this cycle is meiosis, a specialized cell division process that ensures genetic diversity. In bryophytes, meiosis occurs within the sporophyte, the diploid phase of the life cycle, to produce haploid spores. These spores are not merely reproductive units; they are the foundation of the next generation, developing into the gametophyte, which in turn produces gametes for sexual reproduction.

To understand meiosis in bryophytes, consider the sporophyte structure, typically a small, unbranched stalk that grows from the gametophyte. Within the sporophyte’s capsule, spore mother cells undergo meiosis, reducing the chromosome number from diploid to haploid. This process is critical for maintaining the alternation of generations, a hallmark of plant life cycles. Unlike vascular plants, where the sporophyte dominates, bryophytes have a gametophyte-dominated life cycle, yet meiosis remains a key event in the sporophyte phase. For example, in mosses, the sporophyte capsule, or sporangium, releases spores through a structure called the peristome, which regulates spore dispersal.

Practical observation of meiosis in bryophytes can be achieved by examining mature sporophytes under a microscope. Look for the spore mother cells within the capsule, which will show signs of meiotic division, such as chromosome pairing and separation. This process typically occurs in controlled environmental conditions, as sporophyte development is sensitive to factors like humidity and light. For educators or enthusiasts, collecting samples from moist, shaded habitats increases the likelihood of finding mature sporophytes ready for analysis.

Comparatively, meiosis in bryophytes differs from that in vascular plants in its timing and structural context. In vascular plants, the sporophyte is the dominant phase, and meiosis often occurs in specialized structures like flowers or cones. In bryophytes, the sporophyte is nutritionally dependent on the gametophyte, and meiosis is confined to the capsule, a simpler structure. This distinction highlights the evolutionary divergence in plant life cycles and the adaptability of meiosis across different plant groups.

In conclusion, meiosis in the bryophyte life cycle is a precise and essential process that ensures genetic diversity and sustains the alternation of generations. By producing haploid spores, it bridges the gap between the sporophyte and gametophyte phases, maintaining the continuity of the species. Understanding this process not only sheds light on bryophyte biology but also provides insights into the broader mechanisms of plant reproduction and evolution. Whether for academic study or personal exploration, observing meiosis in bryophytes offers a window into the intricate world of plant life cycles.

How to Register an EA Account for Spore: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Sporophyte Structure and Function

Bryophytes, including mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, are unique in their reproductive strategies, particularly in how they produce spores. Unlike vascular plants, bryophytes have a dominant gametophyte phase, but their sporophyte generation is still crucial for completing their life cycle. The sporophyte in bryophytes is structurally simpler compared to ferns or seed plants, yet it serves a vital function in spore production through meiosis. This structure typically consists of a sporangium, a foot, and a seta. The foot anchors the sporophyte to the gametophyte and absorbs nutrients, while the seta elevates the sporangium, facilitating spore dispersal.

Analyzing the sporophyte’s function reveals its primary role in meiosis, the process that reduces the chromosome number by half, producing haploid spores. In bryophytes, the sporangium houses the sporogenous tissue where meiosis occurs. This process ensures genetic diversity, a critical advantage for organisms often exposed to fluctuating environments. For example, moss sporophytes release spores that can disperse over long distances, increasing the species’ ability to colonize new habitats. Understanding this mechanism highlights the sporophyte’s significance beyond its modest structure.

To observe sporophyte function in bryophytes, consider a practical experiment: collect a moss species like *Sphagnum* and examine its sporophytes under a dissecting microscope. Note the capsule-like sporangium atop the slender seta. Gently open the sporangium to observe the spore-producing cells. This hands-on approach demonstrates how meiosis occurs within the sporophyte, producing spores that will later germinate into protonema, the juvenile stage of the gametophyte. Such activities are ideal for educational settings, offering tangible insights into plant reproduction.

Comparatively, the sporophyte in bryophytes is short-lived and dependent on the gametophyte for nutrition, contrasting sharply with vascular plants where the sporophyte is the dominant phase. This dependency underscores the bryophyte’s evolutionary position as a transitional group between algae and more complex plants. Despite its simplicity, the sporophyte’s role in meiosis and spore production is a cornerstone of bryophyte survival, ensuring their persistence in diverse ecosystems, from arctic tundras to tropical rainforests.

In conclusion, the sporophyte in bryophytes, though structurally simple, is functionally indispensable. Its role in producing spores through meiosis not only ensures genetic diversity but also facilitates the species’ adaptability and dispersal. By examining its structure and function, we gain a deeper appreciation for the evolutionary ingenuity of these early land plants. Whether in a classroom or a field study, exploring the sporophyte offers valuable lessons in botany and ecology.

Can Air Filters Effectively Trap and Prevent Mold Spores?

You may want to see also

Spore Formation Process

Bryophytes, including mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, are non-vascular plants that reproduce via spores. A critical question arises: are these spores produced by meiosis? The answer is yes. Spore formation in bryophytes is a meiotic process, ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability. This process occurs within the sporangium, a specialized structure that develops on the gametophyte generation of the plant. Meiosis, a type of cell division, reduces the chromosome number by half, producing haploid spores capable of growing into new individuals under favorable conditions.

The spore formation process in bryophytes begins with the maturation of the sporangium. Inside this structure, sporocytes (spore mother cells) undergo meiosis, dividing twice to produce four haploid spores. This reduction division is essential for maintaining the alternation of generations in bryophytes, where the gametophyte (haploid) and sporophyte (diploid) phases alternate. Unlike vascular plants, bryophytes have a dominant gametophyte phase, and the sporophyte remains dependent on it for nutrition. The spores, once released, can disperse via wind or water, germinating into protonema—a filamentous structure that eventually develops into a new gametophyte.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore formation in bryophytes is crucial for conservation and horticulture. For instance, mosses are increasingly used in green roofs and urban landscaping due to their ability to retain water and withstand harsh conditions. Propagating these plants via spores requires controlled environments to mimic natural dispersal and germination conditions. Collectors and researchers often use sterile techniques to harvest spores, placing them in growth media with specific pH levels (typically 5.0–6.5) and humidity (80–90%) to encourage protonema development. This process highlights the importance of meiosis in producing viable spores for sustainable cultivation.

Comparatively, the spore formation process in bryophytes contrasts with that of ferns and seed plants. While all three groups rely on meiosis for spore production, bryophytes lack true vascular tissue, resulting in simpler sporangia and more direct spore dispersal mechanisms. For example, mosses often have capsule-like sporangia that dry out and split open, releasing spores explosively. In contrast, ferns have more complex sporangia (often clustered into sori) that rely on humidity for gradual spore release. This comparison underscores the evolutionary adaptations of bryophytes to thrive in moist, shaded environments where water is essential for fertilization.

In conclusion, the spore formation process in bryophytes is a meiotic event that ensures genetic diversity and survival. From a scientific perspective, it exemplifies the alternation of generations, a fundamental concept in plant biology. Practically, it enables the propagation of bryophytes for ecological and aesthetic purposes. By studying this process, we gain insights into the resilience of these ancient plants and their role in modern ecosystems. Whether for research, conservation, or horticulture, understanding spore formation in bryophytes is a key to unlocking their potential.

Black Mold Spores in Gypsum: Risks, Detection, and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Genetic Diversity in Spores

Bryophytes, including mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, produce spores through meiosis, a process that ensures genetic diversity by shuffling and recombining genetic material. This mechanism is crucial for their survival in diverse and often harsh environments. Unlike vascular plants, bryophytes rely solely on spores for reproduction and dispersal, making the genetic variability within these spores a key factor in their adaptability. Meiosis introduces unique genetic combinations in each spore, allowing bryophyte populations to respond to environmental pressures such as climate change, disease, or habitat fragmentation.

To understand the practical implications of this genetic diversity, consider the role of spores in colonizing new habitats. When a bryophyte releases spores, each carries a distinct genetic profile, increasing the likelihood that at least some will thrive in varying conditions. For instance, spores with genes resistant to drought or salinity can establish themselves in arid or coastal environments, while others may excel in shaded, moist areas. This natural selection process is amplified by the sheer number of spores produced—a single moss plant can release millions of spores annually, maximizing the potential for successful colonization.

However, maintaining genetic diversity in spores is not without challenges. Inbreeding, which can occur in isolated populations, reduces genetic variability and increases susceptibility to environmental stressors. Conservation efforts must therefore focus on preserving diverse bryophyte habitats to ensure ongoing genetic recombination. For enthusiasts cultivating bryophytes, introducing spores from multiple sources can mimic natural diversity, enhancing the resilience of cultivated populations. For example, mixing spores from different moss species in a terrarium can create a genetically robust ecosystem capable of withstanding fluctuations in humidity or light.

A comparative analysis highlights the contrast between bryophytes and seed plants in spore diversity. While seed plants invest energy in protecting and nourishing seeds, bryophytes prioritize quantity and variability in spores. This strategy reflects their evolutionary adaptation to unpredictable environments, where rapid dispersal and genetic flexibility are more critical than resource-intensive seed development. By studying these differences, researchers can gain insights into the trade-offs between reproductive strategies and their ecological consequences.

In conclusion, the genetic diversity in bryophyte spores, generated through meiosis, is a cornerstone of their evolutionary success. This diversity enables them to colonize diverse habitats, resist environmental challenges, and maintain population health. Whether in natural ecosystems or cultivated settings, understanding and preserving this genetic variability is essential for the long-term survival of these ancient plants. Practical steps, such as habitat conservation and thoughtful cultivation practices, can ensure that bryophytes continue to thrive in an ever-changing world.

Are Anthrax Spores Lurking in Fields? Uncovering the Hidden Danger

You may want to see also

Comparison with Other Plant Spores

Bryophytes, including mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, produce spores through meiosis, a process shared with other plant groups like ferns, lycophytes, and seed plants. However, the lifecycle and spore function in bryophytes differ significantly. In bryophytes, spores germinate directly into a gametophyte-dominant generation, whereas in ferns and seed plants, spores develop into a diminutive gametophyte that remains dependent on the sporophyte. This fundamental distinction highlights bryophytes’ evolutionary position as a bridge between non-vascular and vascular plants.

Consider the spore dispersal mechanisms across plant groups. Bryophytes release spores from a sporangium (capsule) often elevated on a seta, relying on wind for dispersal. Ferns, in contrast, use similar wind-dispersal strategies but produce larger spores in greater quantities. Seed plants, however, have evolved more sophisticated methods, such as pollen grains in gymnosperms and angiosperms, which are smaller, more numerous, and often transported by animals or water. This comparison underscores bryophytes’ simpler, ancestral approach to spore dissemination.

Analyzing spore wall composition reveals another layer of comparison. Bryophyte spores possess a thick, resistant wall made of sporopollenin, a trait shared with ferns and lycophytes. This durability allows spores to survive harsh conditions, a critical adaptation for plants lacking true roots, stems, or leaves. Seed plants, however, invest energy in protecting their reproductive units (seeds) rather than individual spores, reducing reliance on sporopollenin. This divergence illustrates how bryophytes prioritize spore resilience over complex reproductive structures.

Practical observations can deepen understanding. For instance, in a classroom or lab setting, compare bryophyte spores under a microscope to those of ferns or pollen grains of angiosperms. Note the size, shape, and wall thickness differences. Bryophyte spores are typically smaller (10–50 μm) and more uniform than fern spores (20–100 μm), which often exhibit intricate ornamentation. This hands-on approach reinforces the evolutionary and functional distinctions among plant spores.

In conclusion, while all these plants produce spores via meiosis, bryophytes stand out for their gametophyte-centric lifecycle, simple dispersal mechanisms, and reliance on durable spore walls. These traits position bryophytes as a critical reference point for understanding plant evolution. By comparing their spores to those of ferns and seed plants, one gains insight into the adaptive strategies that have shaped plant diversity over millions of years.

Buying Death Cap Spores: Legal, Ethical, and Safety Concerns Explored

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, bryophytes produce spores through the process of meiosis, which is a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in haploid spores.

Meiosis occurs in the sporophyte stage of the bryophyte life cycle, where the sporangium (spore-producing structure) undergoes meiosis to generate haploid spores.

The spores produced by meiosis in bryophytes are haploid, as meiosis reduces the chromosome number from diploid (2n) to haploid (n).

After release, the haploid spores germinate to form the gametophyte generation, which is the dominant and independent phase in the bryophyte life cycle.