Chytrids, a group of fungi belonging to the phylum Chytridiomycota, are unique among fungi due to their production of flagellated spores, known as zoospores. Unlike most fungi that rely on non-motile spores for dispersal, chytrids utilize these zoospores, which are equipped with a single posterior flagellum, to swim through aqueous environments in search of suitable substrates or hosts. This characteristic motility distinguishes chytrids from other fungal groups and highlights their evolutionary adaptation to aquatic and moist habitats. The presence of flagellated spores is a defining feature of chytrids, playing a crucial role in their life cycle, ecology, and interactions with their environment.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do Chytrids have flagellated spores? | Yes |

| Type of Spores | Zoospores (flagellated) |

| Function of Flagella | Enable motility for dispersal and locating suitable substrates |

| Number of Flagella per Zoospore | Typically one, though some species may have more |

| Life Cycle Stage | Zoospores are part of the asexual reproductive phase |

| Ecological Role | Decomposers, parasites, or symbionts in aquatic and terrestrial habitats |

| Taxonomic Group | Kingdom Fungi, Division Chytridiomycota |

| Significance | Important in nutrient cycling and ecosystem dynamics |

| Examples of Chytrid Species | Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (causes chytridiomycosis in amphibians) |

| Habitat | Primarily aquatic or moist environments |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Chytrid Life Cycle Stages: Do all stages include flagellated spores, or is it specific to certain phases

- Flagellum Function: What role does the flagellum play in chytrid spore dispersal and survival

- Species Variation: Do all chytrid species produce flagellated spores, or is it species-specific

- Environmental Impact: How does the presence of flagellated spores affect chytrid ecology and habitat

- Comparative Analysis: How do chytrid flagellated spores differ from those of other fungal groups

Chytrid Life Cycle Stages: Do all stages include flagellated spores, or is it specific to certain phases?

Chytrids, often referred to as fungal organisms, exhibit a unique life cycle that sets them apart from other fungi. One of the most intriguing aspects of their life cycle is the presence of flagellated spores, which play a crucial role in their dispersal and survival. However, the question arises: do all stages of the chytrid life cycle include flagellated spores, or is this feature specific to certain phases? To answer this, let's delve into the distinct stages of the chytrid life cycle and examine the role of flagellated spores in each.

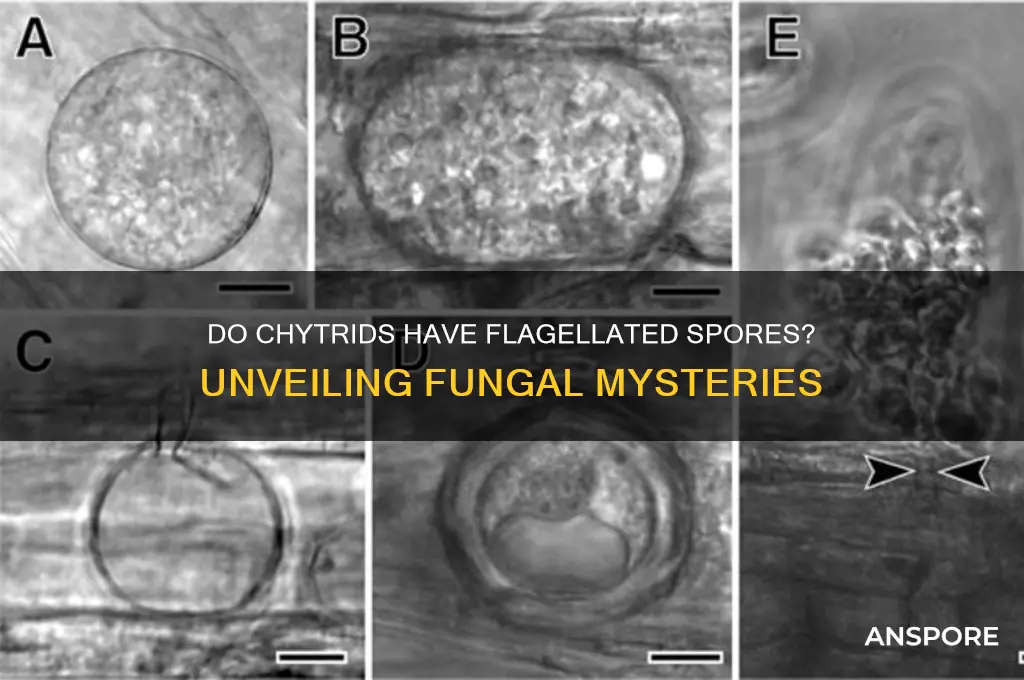

The chytrid life cycle begins with a sporangium, a structure that contains numerous zoospores, which are flagellated spores. These zoospores are released into the surrounding environment, where they swim using their flagella to locate a suitable substrate. This initial stage highlights the importance of flagellated spores in the early phases of the chytrid life cycle, as they enable the organism to disperse and colonize new habitats. For instance, in aquatic environments, zoospores can swim towards nutrient-rich areas, ensuring the chytrid's survival and proliferation.

As the life cycle progresses, the zoospore encysts upon finding a suitable surface, forming a germ tube that penetrates the substrate. This marks the transition to the mycelial stage, where the chytrid grows and develops. Notably, this stage does not involve flagellated spores; instead, the organism focuses on nutrient absorption and growth. The absence of flagellated spores in this phase suggests that their role is specific to dispersal rather than continuous mobility throughout the entire life cycle.

The final stage involves the production of new sporangia, which give rise to the next generation of zoospores. This cyclical process underscores the strategic use of flagellated spores in chytrids. By limiting flagellated spores to the dispersal phase, chytrids optimize energy expenditure, ensuring that resources are allocated efficiently to growth, reproduction, and survival. For example, in laboratory settings, researchers often observe that chytrids produce zoospores in response to environmental cues, such as nutrient depletion, further emphasizing the targeted use of these spores.

In practical terms, understanding the specific role of flagellated spores in the chytrid life cycle has implications for managing chytridiomycosis, a disease caused by chytrids that affects amphibians. By targeting the zoospore stage, interventions such as chemical treatments or environmental modifications can disrupt the dispersal mechanism, potentially mitigating the spread of the disease. For instance, maintaining water quality in amphibian habitats can reduce the viability of zoospores, thereby protecting vulnerable species.

In conclusion, not all stages of the chytrid life cycle include flagellated spores; their presence is specific to the dispersal phase, particularly in the zoospore stage. This specialization allows chytrids to efficiently colonize new environments while conserving energy during other life cycle stages. Recognizing this distinction provides valuable insights into both the biology of chytrids and the development of strategies to address chytrid-related challenges.

Are Psilocybe Cubensis Spores Illegal in Florida? Legal Insights

You may want to see also

Flagellum Function: What role does the flagellum play in chytrid spore dispersal and survival?

Chytrids, a group of fungi, are unique in the fungal kingdom due to their possession of flagellated spores, known as zoospores. These zoospores are equipped with a single, posteriorly directed flagellum, a whip-like structure that enables them to swim through aqueous environments. This flagellum is not merely a vestigial feature but a critical adaptation for spore dispersal and survival in wet habitats. The rhythmic, undulating motion of the flagellum propels the zoospore through water films, allowing it to reach new substrates and colonize diverse environments, from soil to aquatic ecosystems.

The function of the flagellum in chytrid spore dispersal is twofold: active movement and environmental sensing. As the flagellum beats, it generates thrust, enabling the zoospore to navigate through liquid mediums with precision. This active motility is essential for chytrids, as it allows them to escape unfavorable conditions, such as nutrient depletion or predation, and seek out more hospitable environments. For instance, zoospores can swim toward chemical gradients, a process known as chemotaxis, to locate food sources or suitable substrates for germination. This sensory capability enhances their survival by ensuring they settle in optimal locations for growth and reproduction.

From a survival perspective, the flagellum also plays a pivotal role in the life cycle of chytrids. Once a zoospore reaches a suitable substrate, it encysts, loses its flagellum, and germinates to form a new thallus. This transition from motile zoospore to sessile thallus is a critical phase, as it marks the shift from dispersal to colonization. The flagellum, therefore, is not just a tool for movement but a transient structure that facilitates the chytrid's dual lifestyle—mobile and sessile. This adaptability is key to their success in diverse and often challenging environments.

To illustrate the practical implications of flagellum function, consider the impact of chytrids on amphibian populations. The chytrid fungus *Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis* (Bd) disperses via flagellated zoospores, which can swim through water to infect new hosts. Understanding the role of the flagellum in spore motility has led to targeted strategies for disease control, such as disrupting water flow in habitats to limit zoospore dispersal. Additionally, researchers are exploring ways to inhibit flagellar function as a means of curbing chytrid infections, highlighting the flagellum's central role in both the fungus's ecology and its pathogenicity.

In summary, the flagellum in chytrid spores is a multifunctional organelle that drives dispersal, enables environmental sensing, and supports survival in dynamic ecosystems. Its role in active motility and chemotaxis ensures that chytrids can efficiently colonize new substrates, while its transient nature underscores the adaptability of their life cycle. By studying flagellum function, scientists gain insights into chytrid biology and develop strategies to mitigate their impact, whether in ecological contexts or disease management. This highlights the flagellum's significance as a key evolutionary innovation in the fungal kingdom.

Growing Mushrooms from Spores: A Beginner's Guide to Cultivation

You may want to see also

Species Variation: Do all chytrid species produce flagellated spores, or is it species-specific?

Chytrids, a diverse group of fungi, are known for their unique life cycle that includes the production of zoospores. These spores are a defining feature, but not all chytrids follow the same blueprint. The presence of flagellated spores, a characteristic that allows for motility, varies significantly across species. This variation is not random but is deeply rooted in the evolutionary adaptations of different chytrid lineages. For instance, species in the order *Chytridiales* typically produce flagellated zoospores, which enable them to swim through aquatic environments in search of nutrients or hosts. However, not all chytrids adhere to this model, raising the question: is flagellation a universal trait, or does it depend on the species?

To understand this species-specific variation, consider the ecological niches chytrids occupy. Aquatic chytrids, such as those infecting algae or invertebrates, often rely on flagellated spores to disperse efficiently in water. In contrast, chytrids inhabiting soil or plant surfaces may produce non-flagellated spores, as motility is less advantageous in these environments. For example, *Olpidium brassicae*, a soil-dwelling chytrid, lacks flagellated spores, instead relying on passive dispersal mechanisms. This adaptation highlights how environmental pressures shape the reproductive strategies of chytrids, making flagellation a species-specific trait rather than a universal one.

From a taxonomic perspective, the production of flagellated spores is not consistent across all chytrid clades. While the *Chytridiomycota* phylum is traditionally associated with flagellated zoospores, recent phylogenetic studies have revealed exceptions. For instance, members of the order *Spizellomycetales* produce aplanospores, which lack flagella and are dispersed through other means, such as water currents or vectors. This diversity underscores the importance of not generalizing chytrid characteristics based on a few well-studied species. Researchers must consider the broader taxonomic context to accurately describe and predict chytrid behavior.

Practical implications of this species variation are significant, particularly in fields like ecology and disease management. For example, *Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis* (Bd), a chytrid responsible for amphibian declines, produces flagellated zoospores that enable it to infect new hosts efficiently. Understanding whether a chytrid species produces flagellated spores can inform control strategies, such as disrupting water flow to limit spore dispersal. Conversely, non-flagellated species may require different approaches, such as targeting their passive dispersal mechanisms. This knowledge is crucial for developing targeted interventions to mitigate chytrid-related threats.

In conclusion, the production of flagellated spores in chytrids is not a one-size-fits-all trait but varies based on species-specific adaptations and ecological roles. While many chytrids rely on motile spores for survival, others have evolved alternative strategies suited to their environments. Recognizing this variation is essential for both scientific understanding and practical applications, ensuring that approaches to studying or managing chytrids are tailored to their unique characteristics.

Can Dust Masks Effectively Shield You from Mold Spores?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$17.95

Environmental Impact: How does the presence of flagellated spores affect chytrid ecology and habitat?

Chytrids, a group of fungi, are unique in their ability to produce flagellated spores, known as zoospores. These motile spores play a pivotal role in the ecology and habitat of chytrids, influencing their dispersal, colonization, and interaction with the environment. Zoospores are equipped with a single or posterior flagellum, enabling them to swim through aqueous environments, which is critical for their survival and propagation in wet or humid ecosystems. This mobility allows chytrids to access nutrients and colonize substrates that would otherwise be unreachable, such as decaying organic matter in water bodies or damp soil.

The presence of flagellated spores significantly enhances chytrids' adaptability to diverse habitats. For instance, in aquatic environments, zoospores can rapidly disperse across large areas, increasing the fungi's ability to exploit ephemeral nutrient sources. This is particularly evident in ecosystems like wetlands, where chytrids contribute to nutrient cycling by breaking down complex organic materials. In contrast, terrestrial chytrids utilize zoospores to navigate thin water films on soil surfaces or plant tissues, ensuring their survival in less water-saturated conditions. This adaptability underscores the ecological importance of chytrids as decomposers and their role in maintaining ecosystem health.

However, the environmental impact of flagellated spores extends beyond beneficial ecological functions. Chytrids, such as *Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis* (Bd), the causative agent of chytridiomycosis in amphibians, highlight the darker side of zoospore mobility. Bd zoospores can efficiently infect amphibian hosts by swimming through water, contributing to population declines and even extinctions in sensitive species. This demonstrates how the same trait that benefits chytrids in nutrient acquisition can have devastating effects on biodiversity when pathogens exploit it. Understanding this dual nature is crucial for managing ecosystems and mitigating the impact of chytrid-related diseases.

To study the environmental impact of flagellated spores, researchers often employ techniques like zoospore trapping and molecular analysis to track dispersal patterns. For example, in laboratory settings, zoospore motility can be quantified using video microscopy, providing insights into their behavior under different environmental conditions. Field studies, on the other hand, may involve monitoring chytrid populations in response to changes in water availability or temperature, which directly affect zoospore viability and dispersal. Practical tips for researchers include maintaining sterile conditions during sampling to avoid contamination and using pH-buffered solutions to preserve zoospore integrity for analysis.

In conclusion, the presence of flagellated spores profoundly shapes chytrid ecology and habitat by enabling efficient dispersal, colonization, and nutrient acquisition. While this trait is essential for their ecological roles as decomposers, it also poses risks when exploited by pathogenic species. By studying zoospore dynamics, scientists can better understand chytrids' environmental impact and develop strategies to protect vulnerable ecosystems. Whether in nutrient cycling or disease management, the mobility of chytrid spores remains a key factor in their interaction with the environment.

Transforming into an Epic Creature in Spore: Possibility or Myth?

You may want to see also

Comparative Analysis: How do chytrid flagellated spores differ from those of other fungal groups?

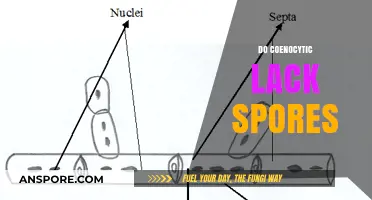

Chytrids are unique among fungi due to their possession of flagellated spores, a feature that sets them apart from other fungal groups. This characteristic is a defining trait of the Chytridiomycota phylum, making it a critical point of comparison in fungal biology. While most fungi rely on non-motile spores for dispersal, chytrids have evolved a distinct strategy, utilizing flagella for movement, which is more commonly associated with protists and certain bacteria. This motility allows chytrid spores to actively seek out favorable environments, a capability that other fungal spores lack.

The Mechanism of Motility: A Comparative Perspective

Chytrid flagellated spores, known as zoospores, are propelled by a single posterior flagellum, enabling them to swim through aqueous environments. This contrasts sharply with the dispersal methods of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, which release non-motile spores that rely on wind, water, or vectors for transport. For instance, the asexual spores of molds (Ascomycota) are typically dispersed passively, while the basidiospores of mushrooms (Basidiomycota) are ejected into the air. The active motility of chytrid zoospores not only enhances their dispersal efficiency but also allows them to colonize habitats inaccessible to non-motile spores, such as aquatic ecosystems.

Structural and Functional Differences

The flagellated spores of chytrids are structurally simpler than the multicellular fruiting bodies of other fungi. Unlike the complex structures of mushrooms or the asci of yeasts, chytrid zoospores are unicellular and transient, existing only during the dispersal phase. This simplicity is offset by their functional adaptability; the flagellum is a highly specialized organelle that requires precise coordination of microtubules and motor proteins. In contrast, the spores of other fungi invest energy in developing thick cell walls or elaborate dispersal mechanisms, such as the forcible discharge of basidiospores.

Ecological Implications

The flagellated spores of chytrids confer a competitive advantage in specific ecological niches. For example, chytrids thrive in aquatic and moist environments where water facilitates zoospore movement. This contrasts with the terrestrial dominance of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, whose spores are adapted for air dispersal. However, this specialization also limits chytrids to habitats with sufficient water, whereas other fungi can colonize a broader range of environments. Understanding these differences is crucial for predicting fungal distribution and their roles in ecosystems, particularly in the context of climate change and habitat alteration.

Practical Considerations and Applications

From a practical standpoint, the motility of chytrid spores has implications for disease management and biotechnology. For instance, *Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis*, a chytrid responsible for amphibian declines, uses zoospores to infect hosts, making water treatment and containment strategies essential. In contrast, managing diseases caused by non-motile fungal spores, such as powdery mildew, relies on fungicides and resistant cultivars. Additionally, the unique biology of chytrid zoospores has inspired biotechnological applications, such as using their enzymes for biomass degradation. By studying these differences, researchers can develop targeted interventions and harness the potential of chytrids in industrial processes.

In summary, chytrid flagellated spores differ from those of other fungal groups in their motility, structure, ecological niche, and practical implications. These distinctions highlight the evolutionary divergence of Chytridiomycota and underscore their significance in both natural and applied contexts.

Exploring Soridium: Unveiling the Presence of Fungus Spores Within

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, chytrids produce flagellated spores called zoospores, which are a defining characteristic of the group.

Flagellated spores (zoospores) in chytrids allow them to swim through water or moist environments to find new substrates or hosts for colonization.

No, while zoospores are flagellated, chytrids also produce non-motile spores, such as sporangiospores, depending on their life cycle stage.

Chytrid flagellated spores (zoospores) are unique among fungi because they possess a single posterior flagellum, a feature not found in other fungal groups.

Yes, once chytrid zoospores locate a suitable substrate and settle, they lose their flagella and develop into a germling, which grows into a new thallus.