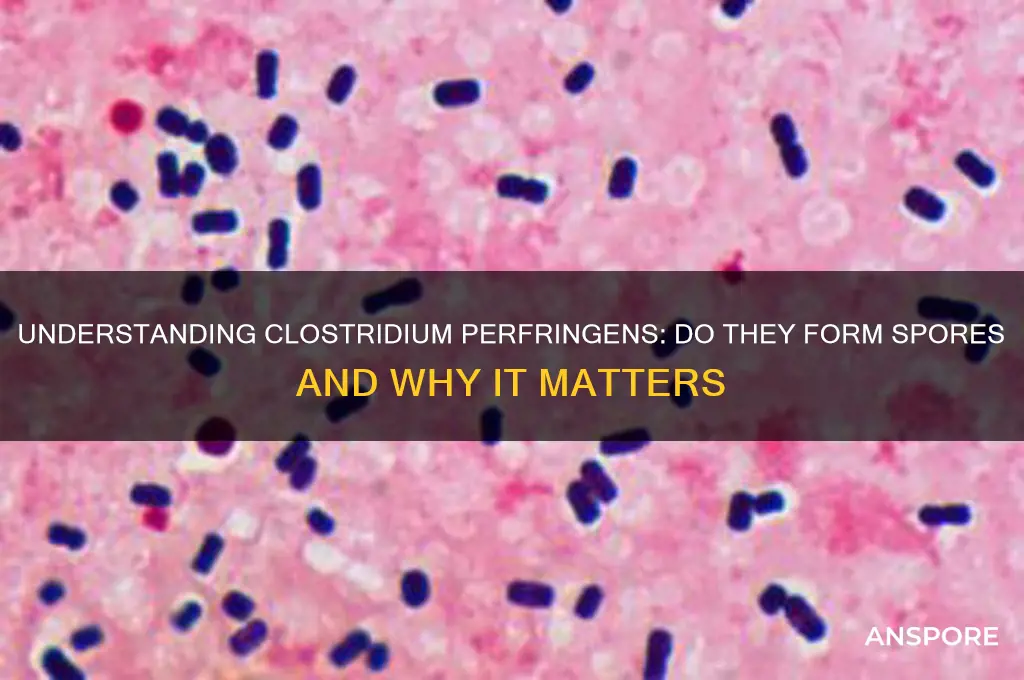

*Clostridium perfringens* is a gram-positive, anaerobic bacterium commonly found in soil, sediments, and the gastrointestinal tracts of humans and animals. Known for its ability to produce potent toxins, this bacterium is a leading cause of foodborne illnesses and various infections, including gas gangrene. One of the most intriguing aspects of *C. perfringens* is its ability to form spores, which are highly resistant structures that allow the bacterium to survive harsh environmental conditions, such as high temperatures, desiccation, and exposure to chemicals. These spores play a crucial role in the bacterium's persistence and transmission, making them a significant focus in understanding its pathogenicity and developing effective control measures.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Sporulation Ability | Yes, Clostridium perfringens is capable of forming spores. |

| Spore Formation Conditions | Sporulation occurs under conditions of nutrient deprivation or stress. |

| Spore Resistance | Spores are highly resistant to heat, desiccation, and chemicals. |

| Spore Structure | Spores are oval or round, with a thick, resistant outer coat. |

| Germination Triggers | Spores germinate in response to nutrients, warmth, and specific cues. |

| Survival in Environment | Spores can survive in soil, water, and gastrointestinal tracts for years. |

| Pathogenicity | Spores can cause disease upon germination in a suitable host. |

| Temperature Tolerance | Spores can withstand temperatures up to 100°C for extended periods. |

| Antimicrobial Resistance | Spores are resistant to most antibiotics and disinfectants. |

| Role in Infection | Spores are the primary mode of transmission for C. perfringens infections. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Conditions: Optimal temperature, pH, and nutrient requirements for C. perfringens spore formation

- Spore Structure: Unique morphological and biochemical characteristics of C. perfringens spores

- Sporulation Mechanism: Genetic and molecular processes involved in C. perfringens spore development

- Spore Survival: Resistance of C. perfringens spores to heat, chemicals, and environmental stressors

- Clinical Significance: Role of spore formation in C. perfringens infections and disease transmission

Sporulation Conditions: Optimal temperature, pH, and nutrient requirements for C. perfringens spore formation

Clostridium perfringens, a Gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium, thrives in environments that support its unique sporulation process. Understanding the optimal conditions for spore formation is crucial for both preventing contamination and harnessing its potential in biotechnological applications. Sporulation is not a random event but a highly regulated process influenced by temperature, pH, and nutrient availability.

Temperature plays a pivotal role in initiating and sustaining sporulation. C. perfringens exhibits optimal spore formation within a narrow temperature range of 37°C to 43°C (98.6°F to 109.4°F). At 37°C, the process is most efficient, aligning with the bacterium’s preference for warm-blooded hosts. Temperatures below 30°C or above 45°C significantly inhibit sporulation, as the metabolic pathways required for spore development are disrupted. For laboratory settings, maintaining a consistent temperature of 37°C in incubators ensures reliable spore production.

PH levels also critically influence sporulation, with C. perfringens favoring a slightly acidic to neutral environment. The optimal pH range for spore formation is 6.0 to 7.4, mirroring conditions found in its natural habitats, such as soil and the gastrointestinal tract. Deviations from this range, particularly toward alkalinity, can halt sporulation. Buffering media to pH 6.5–7.0 using phosphate or acetate buffers is recommended to stabilize conditions and promote efficient spore development.

Nutrient availability is another key factor, as sporulation is an energy-intensive process. C. perfringens requires a balanced supply of carbon and nitrogen sources, with glucose and peptone being particularly effective. Limiting nutrients, especially nitrogen, can trigger sporulation as the bacterium responds to starvation. However, complete deprivation halts the process. A medium containing 1% glucose and 1% peptone, supplemented with trace minerals, provides an ideal nutrient profile. Additionally, the presence of certain amino acids, such as glycine and arginine, enhances sporulation efficiency.

Practical tips for optimizing sporulation include monitoring oxygen levels, as C. perfringens is anaerobic, and using sealed containers or anaerobic chambers. Regularly sampling cultures at 12-hour intervals helps track spore formation progress. For industrial applications, scaling up requires precise control of temperature, pH, and nutrient concentrations to ensure consistent spore yields. Understanding these conditions not only aids in controlling C. perfringens in food safety contexts but also unlocks its potential in spore-based technologies.

Are Mold Spores Classified as VOCs? Unraveling Indoor Air Quality Concerns

You may want to see also

Spore Structure: Unique morphological and biochemical characteristics of C. perfringens spores

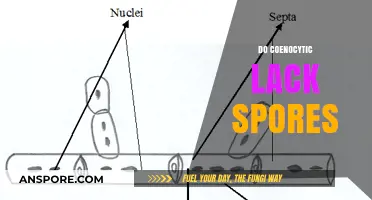

Clostridium perfringens, a Gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium, produces spores with distinct morphological and biochemical features that set them apart from other bacterial spores. These characteristics are critical for their survival in harsh environments and their role in pathogenesis. Morphologically, C. perfringens spores are oval-shaped and typically located centrally or subterminally within the bacterial cell, a feature that aids in their identification under microscopy. Unlike the spores of Bacillus species, which often exhibit a more pronounced refractivity, C. perfringens spores are less refractile and may appear more translucent, making them slightly more challenging to visualize without specialized staining techniques.

Biochemically, the spore structure of C. perfringens is fortified with a unique composition of proteins and lipids that contribute to its resilience. The spore coat, for instance, is rich in proteins like cotE and cotG, which play a role in spore germination and resistance to environmental stressors. Additionally, the exosporium, an outer layer surrounding the spore, contains glycoproteins and lipids that enhance adhesion to surfaces and protect against desiccation and heat. This layer is particularly significant in C. perfringens, as it facilitates the spore's ability to persist in soil, food, and the gastrointestinal tract, where it can cause infections.

One of the most intriguing aspects of C. perfringens spores is their ability to germinate rapidly under specific conditions, such as exposure to certain nutrients like amino acids and simple sugars. This rapid germination is facilitated by the presence of germinant receptors in the spore's inner membrane, which are highly sensitive to specific triggers. For example, L-alanine, L-cysteine, and inosine are known to induce germination in C. perfringens spores, a process that occurs within minutes under optimal conditions. This rapid response is crucial for the bacterium's lifecycle, allowing it to quickly transition from a dormant state to an active, vegetative form when favorable conditions arise.

Practical implications of understanding C. perfringens spore structure include improved strategies for food safety and medical treatment. For instance, knowing that these spores can survive cooking temperatures up to 100°C underscores the importance of proper food handling and storage. To inactivate C. perfringens spores in food, it is recommended to heat items to at least 74°C (165°F) for a minimum of 15 seconds, ensuring thorough cooking and reheating. In medical settings, recognizing the unique biochemical markers of these spores can aid in the development of targeted therapies, such as spore germinant inhibitors, to prevent spore activation and subsequent infection.

In summary, the spore structure of C. perfringens is characterized by unique morphological and biochemical traits that enhance its survival and pathogenic potential. From its distinct shape and composition to its rapid germination mechanisms, these features make C. perfringens spores a subject of significant interest in both microbiology and applied sciences. By understanding these characteristics, researchers and practitioners can develop more effective strategies to control and mitigate the risks associated with this bacterium.

Mastering Morel Mushroom Propagation: Effective Techniques to Spread Spores

You may want to see also

Sporulation Mechanism: Genetic and molecular processes involved in C. perfringens spore development

Clostridium perfringens, a Gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium, initiates sporulation in response to nutrient deprivation, particularly the depletion of carbon and nitrogen sources. This process is tightly regulated by a cascade of genetic and molecular events, ensuring survival in harsh environments. The sporulation mechanism in *C. perfringens* is less complex than in *Bacillus subtilis* but shares fundamental regulatory elements, such as the master regulator Spo0A, which activates sporulation genes upon phosphorylation. Understanding this mechanism is crucial for developing strategies to control *C. perfringens* contamination in food and medical settings, as spores are highly resistant to heat, desiccation, and chemicals.

The sporulation process begins with asymmetric cell division, forming a smaller forespore and a larger mother cell. This division is orchestrated by the SpoIIE protein, which localizes to the septum and activates sigma factor σ^F in the forespore. Sigma factors play a pivotal role in *C. perfringens* sporulation, sequentially activating gene expression in both compartments. For instance, σ^F drives early forespore-specific genes, while σ^E controls mother cell-specific genes, such as those encoding enzymes for cortex synthesis. Unlike *B. subtilis*, *C. perfringens* lacks σ^G activity, simplifying its sporulation pathway but maintaining efficiency in spore formation.

Genetic studies have identified key operons, such as the *spoIIA* operon, which encodes proteins essential for sigma factor activation. Mutations in these operons disrupt sporulation, highlighting their critical role. Additionally, the *spo0A* gene is central to the phosphorelay system, a signaling cascade that responds to environmental stressors. Phosphorylated Spo0A binds to promoters of sporulation genes, initiating the process. Notably, *C. perfringens* spores lack the calcium dipicolinate core found in *B. subtilis* spores, yet they retain remarkable resistance, suggesting alternative mechanisms for spore stability.

Molecularly, the spore coat and exosporium are assembled in the mother cell, providing structural integrity and protection. The coat proteins, encoded by genes like *cotA* and *cotB*, are synthesized under σ^K control in the late stages of sporulation. The exosporium, a loosely attached outer layer, contains proteins such as BclA, which contribute to spore adhesion and immune evasion. Interestingly, *C. perfringens* spores are often associated with foodborne illnesses, as their heat resistance allows survival in undercooked meats. Practical tips for reducing spore contamination include cooking foods to ≥74°C (165°F) and avoiding prolonged storage at room temperature.

In conclusion, the sporulation mechanism of *C. perfringens* is a genetically and molecularly orchestrated process, driven by sigma factors, Spo0A, and specific operons. While less complex than in *B. subtilis*, it ensures robust spore formation, posing challenges in food safety and medical contexts. Targeting these pathways could lead to novel antimicrobial strategies, emphasizing the importance of understanding this mechanism in applied settings.

Troubleshooting Spore Server Connection Issues: Solutions and Fixes

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spore Survival: Resistance of C. perfringens spores to heat, chemicals, and environmental stressors

Clostridium perfringens is a spore-forming bacterium notorious for its resilience, particularly in the food industry and healthcare settings. Its spores can withstand extreme conditions, making them a significant challenge for sterilization and disinfection processes. Understanding their resistance mechanisms is crucial for developing effective strategies to combat contamination.

Heat Resistance: A Formidable Barrier

C. perfringens spores are remarkably heat-resistant, surviving temperatures that would destroy most vegetative cells. For instance, they can endure exposure to 70°C (158°F) for up to 30 minutes, and even 100°C (212°F) for several minutes. This resilience is attributed to their thick protein coat and low water content, which protect the spore’s DNA. In food processing, this necessitates the use of autoclaving at 121°C (250°F) for 15–30 minutes to ensure complete spore destruction. Failure to reach these parameters can lead to foodborne outbreaks, as seen in cases of improperly cooked meats or reheated foods.

Chemical Resistance: A Complex Challenge

Chemicals commonly used for disinfection, such as chlorine and quaternary ammonium compounds, are often ineffective against C. perfringens spores. Spores possess a highly impermeable outer layer that prevents chemical penetration. For example, 100 ppm chlorine, a standard disinfectant concentration, may reduce spore counts but rarely eliminates them entirely. More potent agents like hydrogen peroxide or peracetic acid are required, with concentrations of 1–2% needed for effective spore inactivation. Even then, organic matter in the environment can reduce chemical efficacy, highlighting the need for meticulous cleaning protocols before disinfection.

Environmental Stressors: Adaptability in Action

C. perfringens spores thrive in diverse environments, from soil to the human gut, due to their ability to resist desiccation, UV radiation, and pH extremes. They can remain viable in soil for years, posing a risk in agricultural settings. UV radiation, commonly used for surface disinfection, is largely ineffective against spores due to their DNA repair mechanisms. Additionally, spores can survive in pH ranges from 4.5 to 9.0, though they are most stable in neutral to slightly alkaline conditions. This adaptability underscores the importance of multi-faceted control measures, such as combining physical (heat) and chemical treatments.

Practical Strategies for Control

To mitigate the risks posed by C. perfringens spores, a combination of strategies is essential. In food handling, ensure thorough cooking to internal temperatures of 74°C (165°F) and prompt refrigeration below 4°C (39°F) to prevent spore germination. For healthcare settings, use spore-specific disinfectants like hydrogen peroxide or glutaraldehyde, and follow manufacturer guidelines for concentration and contact time. In industrial processes, implement validation studies to confirm sterilization efficacy, particularly in autoclaves or pasteurization systems. Regular monitoring and staff training are equally critical to prevent cross-contamination and ensure compliance with safety protocols.

Takeaway: A Multifaceted Approach is Key

The resistance of C. perfringens spores to heat, chemicals, and environmental stressors demands a comprehensive strategy. No single method is foolproof; instead, a combination of physical, chemical, and procedural measures is required. By understanding their survival mechanisms, we can design targeted interventions that minimize the risk of contamination and protect public health. Whether in food production, healthcare, or environmental management, vigilance and adaptability are paramount in the fight against these resilient spores.

Save Spore Creatures: Modding Tips for Preservation and Gameplay

You may want to see also

Clinical Significance: Role of spore formation in C. perfringens infections and disease transmission

Clostridium perfringens, a Gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium, is a significant pathogen in both human and animal health. Its ability to form spores plays a critical role in its survival, persistence, and transmission, making it a formidable agent of disease. Spores are highly resistant structures that can withstand extreme conditions, including heat, desiccation, and chemicals, allowing C. perfringens to persist in diverse environments such as soil, water, and food. This resilience enables the bacterium to remain dormant until it encounters favorable conditions for germination and growth, thereby increasing its potential to cause infections.

The clinical significance of spore formation in C. perfringens infections lies in its ability to facilitate disease transmission and recurrence. Spores can contaminate food products, particularly meat and poultry, which, when improperly cooked or stored, can lead to foodborne illnesses. For instance, ingestion of spores in undercooked meat can result in enterotoxemia, characterized by abdominal pain, diarrhea, and, in severe cases, dehydration. The heat-resistant nature of spores means they can survive cooking temperatures that would kill vegetative cells, posing a challenge for food safety protocols. To mitigate this risk, it is essential to cook meat thoroughly (internal temperature of 165°F or 74°C) and refrigerate leftovers promptly to prevent spore germination.

Another critical aspect of spore formation is its role in chronic and recurrent infections. Spores can colonize the gastrointestinal tract, where they may remain dormant until triggered by factors such as antibiotic use, dietary changes, or immunosuppression. This can lead to conditions like antibiotic-associated diarrhea or necrotizing enterocolitis, particularly in vulnerable populations such as the elderly, infants, and immunocompromised individuals. For example, in healthcare settings, spores can contaminate medical equipment or surfaces, serving as a reservoir for nosocomial infections. Rigorous disinfection protocols, including the use of spore-specific sterilants like hydrogen peroxide or autoclaving, are crucial to prevent transmission in clinical environments.

Comparatively, the ability of C. perfringens to form spores distinguishes it from non-spore-forming pathogens, as it ensures long-term environmental survival and increases the likelihood of exposure. Unlike vegetative cells, spores do not actively replicate but can rapidly germinate and multiply once conditions are favorable, leading to sudden outbreaks. This underscores the importance of targeted interventions, such as spore-inactivating agents in food processing and healthcare settings. Additionally, understanding the sporulation process can inform the development of novel therapeutics, such as inhibitors of spore germination, to combat C. perfringens infections more effectively.

In summary, the role of spore formation in C. perfringens infections and disease transmission is multifaceted, impacting food safety, clinical outcomes, and public health. By recognizing the unique challenges posed by spores, healthcare professionals, food handlers, and researchers can implement evidence-based strategies to reduce the burden of C. perfringens-related diseases. Practical measures, such as proper cooking techniques, stringent disinfection practices, and targeted therapeutic approaches, are essential to mitigate the risks associated with this spore-forming pathogen.

Do Algae Have Spores? Unveiling the Truth About Algal Reproduction

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Clostridium perfringens is a spore-forming bacterium. It produces endospores under unfavorable environmental conditions, such as nutrient depletion or extreme temperatures.

Clostridium perfringens forms spores in response to harsh conditions like lack of nutrients, oxygen exposure, or extreme temperatures. These spores are highly resistant and allow the bacterium to survive until more favorable conditions return.

The spores themselves are not directly harmful, but they can germinate into active bacteria under suitable conditions, potentially causing infections or foodborne illnesses, such as gas gangrene or diarrhea. Proper cooking and food handling can prevent spore germination and bacterial growth.