Coliforms, a group of bacteria commonly found in the environment and used as indicators of fecal contamination, are primarily non-spore-forming organisms. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as *Clostridium* or *Bacillus*, coliforms do not produce endospores, which are highly resistant structures that allow bacteria to survive harsh conditions. Instead, coliforms, including *Escherichia coli* and other members of the Enterobacteriaceae family, rely on their ability to multiply rapidly in favorable conditions. Their lack of spore formation makes them more susceptible to environmental stressors, such as heat, desiccation, and disinfectants, which is why they are often used as markers for water quality and sanitation. Understanding their non-spore-forming nature is crucial for assessing their presence and significance in various settings, particularly in public health and environmental monitoring.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Coliform spore formation: Do coliform bacteria produce spores as a survival mechanism

- Coliforms vs. spore-formers: How do coliforms differ from spore-forming bacteria like Clostridium

- Coliform survival strategies: What methods do coliforms use instead of spore formation

- Detection of coliform spores: Are there tests to identify spore-like structures in coliforms

- Environmental persistence: How do coliforms survive without spores in harsh conditions

Coliform spore formation: Do coliform bacteria produce spores as a survival mechanism?

Coliform bacteria, commonly found in soil, water, and the intestines of humans and animals, are often used as indicators of fecal contamination. A critical question arises: do these bacteria produce spores as a survival mechanism? The answer lies in understanding the biological capabilities of coliforms. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as *Clostridium* or *Bacillus*, coliforms, including *Escherichia coli*, do not produce spores. This distinction is vital because spore formation is a specialized survival strategy that allows certain bacteria to withstand extreme conditions like heat, desiccation, and chemicals. Coliforms, however, rely on other mechanisms, such as rapid reproduction and biofilm formation, to endure harsh environments.

Analyzing the survival strategies of coliforms reveals why spore formation is absent in these organisms. Coliforms thrive in nutrient-rich environments and have evolved to adapt quickly to changing conditions rather than investing energy in spore production. For instance, *E. coli* can double its population in as little as 20 minutes under optimal conditions, ensuring survival through sheer numbers. Additionally, coliforms form biofilms—structured communities encased in a protective matrix—that shield them from antimicrobial agents and environmental stressors. These adaptations, while effective, differ fundamentally from the dormant, resilient state achieved through spore formation.

From a practical standpoint, the absence of spore formation in coliforms has significant implications for water and food safety protocols. Since coliforms do not produce spores, standard disinfection methods like boiling water (100°C for 1 minute) or using chlorine (1–5 mg/L for 30 minutes) are generally effective in eliminating them. However, their ability to multiply rapidly means that even small populations can quickly recolonize if conditions become favorable. For example, in water treatment plants, continuous monitoring and maintenance are essential to prevent coliform regrowth. Understanding this distinction helps in designing targeted interventions without over-relying on methods aimed at spore-forming bacteria.

Comparatively, the absence of spore formation in coliforms highlights the diversity of bacterial survival strategies. While spore-formers like *Bacillus anthracis* can remain dormant for decades, coliforms prioritize active growth and adaptation. This difference underscores the importance of context-specific approaches in microbial control. For instance, in healthcare settings, coliform contamination is managed through routine sanitation and hygiene practices, whereas spore-forming pathogens require more aggressive measures, such as autoclaving (121°C for 15–20 minutes). Recognizing these distinctions ensures that resources are allocated efficiently in both prevention and remediation efforts.

In conclusion, coliform bacteria do not produce spores as a survival mechanism, relying instead on rapid reproduction and biofilm formation. This biological trait shapes how we detect, control, and mitigate coliform contamination in various settings. By focusing on their unique survival strategies, we can implement more effective and targeted measures to ensure public health and safety. Understanding these specifics not only clarifies the science behind coliform behavior but also empowers practical decision-making in real-world applications.

Mold Spores and Fatigue: Uncovering the Hidden Link to Tiredness

You may want to see also

Coliforms vs. spore-formers: How do coliforms differ from spore-forming bacteria like Clostridium?

Coliforms and spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridium* are both indicators of environmental and food safety, but their survival strategies and implications differ significantly. Coliforms, which include *Escherichia coli* and other gram-negative bacteria, are commonly found in soil, water, and the intestines of warm-blooded animals. Unlike spore-formers, coliforms do not produce spores; instead, they rely on rapid reproduction under favorable conditions, such as temperatures between 20°C and 45°C and nutrient availability. This makes them useful indicators of fecal contamination but also limits their ability to survive harsh conditions like extreme heat, desiccation, or chemical disinfectants.

In contrast, spore-forming bacteria, including *Clostridium* species, produce highly resistant endospores as a survival mechanism. These spores can withstand temperatures above 100°C, prolonged desiccation, and exposure to UV radiation, making them a significant concern in food preservation and sterilization processes. For example, *Clostridium botulinum* spores can survive boiling and germinate in anaerobic, nutrient-rich environments, producing deadly toxins. To eliminate such spores, specific conditions are required, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes or the use of sporicidal chemicals like hydrogen peroxide.

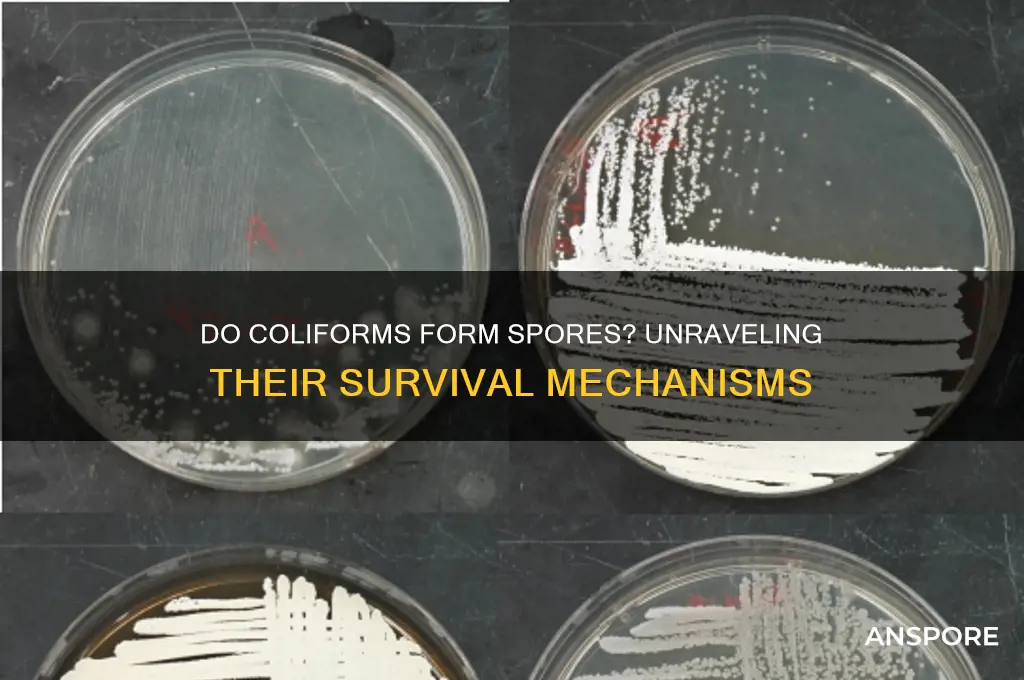

The detection methods for coliforms and spore-formers also differ. Coliforms are typically identified through tests like the Most Probable Number (MPN) or membrane filtration, which assess their ability to ferment lactose and produce acid and gas within 24–48 hours. Spore-formers, however, require more specialized techniques, such as spore staining (e.g., the Schaeffer-Fulton method) or enrichment cultures under anaerobic conditions to encourage spore germination and growth. For instance, *Clostridium perfringens* is detected using sulfite-polymyxin-sulfadiazine (SPS) agar, which suppresses non-spore-forming bacteria.

Practically, understanding these differences is crucial for risk management. Coliform contamination often indicates recent fecal pollution and is addressed through standard sanitation practices, such as chlorination or filtration. Spore-formers, however, require more stringent measures, particularly in food processing, where inadequate heat treatment or storage conditions can lead to spore germination and toxin production. For example, canned foods must be processed in a retort to ensure spore destruction, while perishable items should be stored below 4°C to prevent spore germination.

In summary, while coliforms serve as indicators of immediate contamination and are relatively easy to control, spore-formers pose a long-term threat due to their resilience. Effective management requires tailored strategies: routine hygiene for coliforms and rigorous sterilization for spore-formers. By recognizing these distinctions, industries and individuals can better safeguard public health and ensure product safety.

From Barracks to Beliefs: Can Military Cities Transform into Religious Hubs?

You may want to see also

Coliform survival strategies: What methods do coliforms use instead of spore formation?

Coliform bacteria, unlike spore-forming species such as *Clostridium* or *Bacillus*, lack the ability to produce endospores for long-term survival in harsh conditions. Instead, they rely on a suite of adaptive strategies to endure environmental stresses like desiccation, temperature extremes, and nutrient deprivation. One key method is biofilm formation, where coliforms aggregate and secrete a protective extracellular matrix. This biofilm shields them from antimicrobials, predators, and environmental fluctuations, allowing them to persist on surfaces like pipes, food processing equipment, and even in water systems. For instance, *Escherichia coli*, a common coliform, can form biofilms within 24–48 hours under favorable conditions, significantly enhancing its survival in hostile environments.

Another survival strategy employed by coliforms is their ability to enter a viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state. When exposed to stressors like starvation or disinfectants, coliforms can reduce their metabolic activity to near-zero levels, making them undetectable by standard culturing methods. This state is not permanent; when conditions improve, they can revert to an active, culturable form. Research shows that *E. coli* can remain in the VBNC state for weeks, retaining the potential to cause infection if reintroduced to a suitable environment. This mechanism underscores the challenge of completely eradicating coliforms in settings like water treatment plants or food production facilities.

Coliforms also exploit their rapid replication rate and genetic adaptability to survive. For example, *E. coli* can double every 20 minutes under optimal conditions, enabling quick colonization of new environments. Additionally, horizontal gene transfer allows coliforms to acquire resistance genes, such as those conferring tolerance to antibiotics or heavy metals. A study found that *E. coli* strains in contaminated water sources often carry plasmids encoding multidrug resistance, highlighting their ability to thrive in polluted environments. This adaptability makes them formidable survivors, even without spore formation.

Lastly, coliforms leverage their ability to persist in diverse habitats, from soil and water to the gastrointestinal tracts of animals. Their metabolic versatility allows them to utilize a wide range of carbon sources, ensuring survival in nutrient-limited conditions. For instance, *Klebsiella pneumoniae*, a coliform species, can metabolize complex sugars and even certain alcohols, giving it an edge in environments where other bacteria might struggle. This ecological flexibility, combined with their other survival mechanisms, explains why coliforms are ubiquitous and resilient, despite lacking spores.

In practical terms, understanding these survival strategies is crucial for controlling coliform contamination. Biofilm disruption requires mechanical cleaning or biofilm-specific disinfectants, while VBNC cells may necessitate more stringent monitoring methods. Preventing horizontal gene transfer in coliform populations involves minimizing antibiotic use and reducing environmental pollution. By targeting these specific mechanisms, industries and public health agencies can more effectively mitigate the risks posed by coliforms, even in the absence of spore formation.

Fungal Sexual Spores: Haploid or Diploid? Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Detection of coliform spores: Are there tests to identify spore-like structures in coliforms?

Coliform bacteria, commonly associated with fecal contamination and water quality assessment, are not typically known for producing spores. However, recent studies have sparked curiosity about the existence of spore-like structures in certain coliform strains. This raises the question: can we detect such structures, and what methods are available for their identification?

The Search for Spore-like Structures

In the realm of microbiology, the presence of spores is a distinctive feature, often associated with bacterial resilience and survival in harsh conditions. While coliforms are primarily known for their role as indicators of sanitary quality, some research suggests that specific strains might possess spore-forming capabilities under particular environmental stresses. This phenomenon, though rare, has significant implications for water treatment and food safety. For instance, a study published in the *Journal of Applied Microbiology* (2020) reported the detection of spore-like structures in *E. coli* isolates from wastewater, challenging the conventional understanding of coliform biology.

##

Detection Methods: Unveiling the Invisible

To identify these elusive spore-like structures, microbiologists employ a range of techniques. One common approach is the use of spore stains, such as the Schaeffer-Fulton method, which differentially stains spores, making them visible under a microscope. This technique involves heating the bacterial sample to kill vegetative cells and then applying a primary stain (e.g., malachite green) followed by a counterstain (e.g., safranin). Spores appear green against a pink background, providing a clear indication of their presence. However, this method requires skilled microscopy and may not be suitable for large-scale screening.

Molecular Techniques: A Modern Approach

Advancements in molecular biology offer more precise tools for detecting spore-related genes in coliforms. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) assays can target specific DNA sequences associated with sporulation, such as the *spo0A* gene, a key regulator of spore formation in bacteria. This method is highly sensitive and can detect even low levels of spore-forming cells. For example, a PCR-based study in *Water Research* (2019) successfully identified spore-like coliforms in drinking water sources, highlighting the potential for molecular techniques in routine monitoring.

Practical Considerations and Challenges

While these detection methods provide valuable insights, they are not without limitations. Spore stains, though effective, are time-consuming and subjective, relying on the observer's expertise. PCR, on the other hand, requires specialized equipment and trained personnel, making it less accessible for routine testing. Furthermore, the rarity of spore-forming coliforms means that large sample sizes are often needed to ensure accurate detection.

In practical terms, water treatment facilities and food safety laboratories must balance the need for comprehensive testing with the resources available. Implementing a combination of traditional and molecular methods could be a strategic approach, ensuring both efficiency and accuracy in detecting these unusual coliform variants.

The detection of spore-like structures in coliforms is a fascinating aspect of microbial research, with implications for public health and safety. While not all coliforms produce spores, the existence of such variants underscores the importance of continued exploration and improved detection methods. By employing a range of techniques, from traditional microscopy to modern molecular biology, scientists can unravel the mysteries of these resilient bacteria, ultimately enhancing our ability to safeguard water and food supplies.

Extracting DNA from Bacterial Spores: Techniques, Challenges, and Applications

You may want to see also

Environmental persistence: How do coliforms survive without spores in harsh conditions?

Coliform bacteria, unlike spore-forming organisms such as *Clostridium* or *Bacillus*, lack the ability to produce spores as a survival mechanism. Yet, they persist in diverse and often harsh environments, from soil and water to food processing facilities. This raises the question: how do coliforms endure without the protective advantage of spores? The answer lies in their remarkable adaptability and a suite of survival strategies that enable them to withstand adverse conditions.

One key to coliform survival is their ability to form biofilms, a slimy matrix of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that encases bacterial communities. Biofilms provide a physical barrier against desiccation, UV radiation, and antimicrobial agents. For instance, *Escherichia coli*, a common coliform, can form biofilms on surfaces like pipes or food processing equipment, where it remains viable for weeks. Studies show that biofilm-embedded *E. coli* can tolerate up to 100 times higher concentrations of disinfectants like chlorine compared to planktonic (free-floating) cells. To mitigate this, industries must employ rigorous cleaning protocols, including mechanical scrubbing and the use of biofilm-penetrating agents like enzymes or surfactants.

Another survival mechanism is coliforms' metabolic flexibility. These bacteria can enter a dormant or slow-growing state, known as oligotrophic growth, when nutrients are scarce. In this state, their metabolic activity decreases, reducing energy expenditure and increasing resistance to stressors like temperature extremes or pH fluctuations. For example, coliforms in nutrient-poor water bodies can survive for months by utilizing minimal organic matter. This adaptability underscores the importance of monitoring water quality parameters such as nutrient levels and temperature to prevent coliform proliferation.

Coliforms also exploit their genetic diversity to thrive in harsh conditions. Horizontal gene transfer allows them to acquire resistance genes, enabling survival in environments with antibiotics or heavy metals. A study found that *E. coli* strains isolated from polluted rivers exhibited multidrug resistance, highlighting the role of environmental pressure in shaping bacterial resilience. To combat this, wastewater treatment plants should implement advanced filtration and disinfection methods, such as UV treatment or activated carbon adsorption, to reduce the spread of resistant strains.

Finally, coliforms leverage their short generation time and high reproductive rate to rapidly colonize favorable niches when conditions improve. A single *E. coli* cell can divide every 20 minutes under optimal conditions, quickly establishing a population capable of withstanding subsequent stressors. This underscores the need for proactive environmental management, such as regular sanitation and moisture control, to prevent coliforms from gaining a foothold in critical areas like food production or healthcare settings.

In summary, while coliforms lack spores, their survival in harsh conditions is facilitated by biofilm formation, metabolic flexibility, genetic adaptability, and rapid reproduction. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing effective strategies to control coliform persistence in various environments. By targeting their vulnerabilities, such as disrupting biofilms or limiting nutrient availability, we can minimize their impact on public health and industry.

Are Spores Legal in Nevada? Understanding the Current Laws

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, coliforms do not form spores. They are non-spore-forming bacteria.

Coliforms are less resistant to harsh conditions compared to spore-forming bacteria because they lack spores, which are essential for long-term survival in extreme environments.

No, coliforms are genetically incapable of producing spores, as they lack the necessary cellular mechanisms for spore formation.

Coliforms rely on rapid reproduction and favorable conditions for survival, whereas spore-forming bacteria can enter a dormant spore state to endure harsh environments.