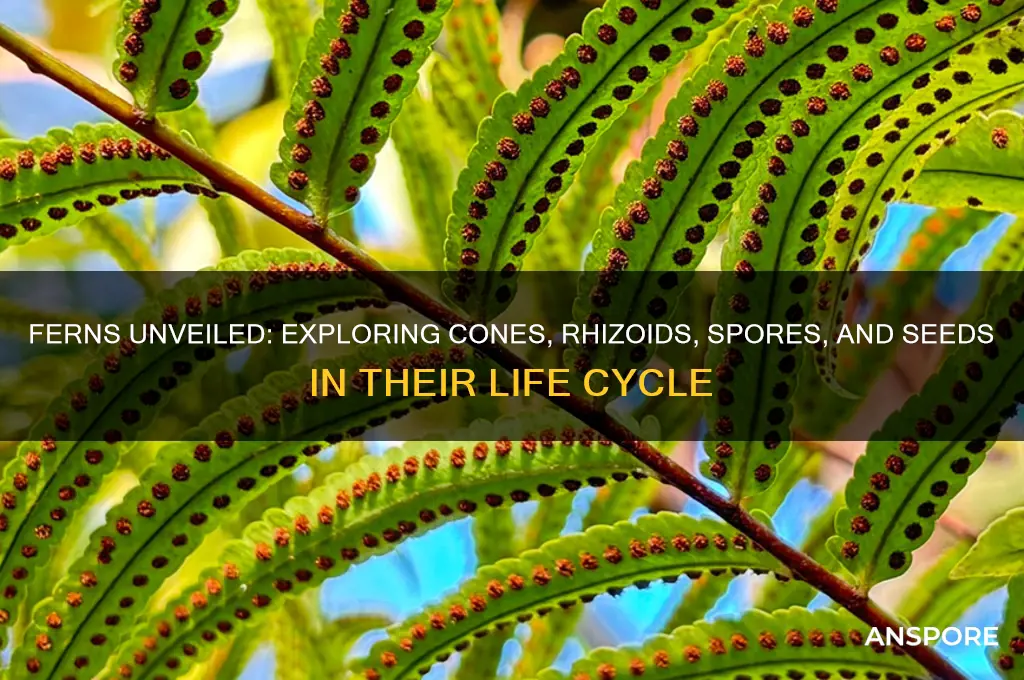

Ferns are unique plants that reproduce through spores rather than seeds, cones, or flowers. Unlike coniferous trees that produce cones or flowering plants that develop seeds, ferns rely on a different reproductive strategy. They generate spores, which are tiny, single-celled structures typically found on the undersides of their fronds in structures called sori. These spores are dispersed by wind or water and, under suitable conditions, develop into a small, heart-shaped gametophyte (prothallus) that produces both male and female reproductive cells. Additionally, ferns often have rhizoids, which are root-like structures that anchor the gametophyte to the substrate and absorb moisture, but they lack true roots, stems, and leaves in the gametophyte stage. This combination of spores and rhizoids distinguishes ferns from other plant groups and highlights their ancient, non-seed-bearing nature.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Ferns and Cones: Ferns do not produce cones; this feature is exclusive to coniferous trees like pines

- Rhizoids in Ferns: Ferns have rhizoids, which anchor them and absorb water and nutrients in gametophytes

- Spores in Ferns: Ferns reproduce via spores, tiny structures released from the undersides of their fronds

- Seeds in Ferns: Ferns lack seeds; they rely on spores for asexual reproduction and dispersal

- Fern Life Cycle: Ferns alternate between sporophyte and gametophyte generations, using spores for propagation

Ferns and Cones: Ferns do not produce cones; this feature is exclusive to coniferous trees like pines

Ferns and coniferous trees, though both ancient plant groups, have distinct reproductive structures that set them apart. One of the most striking differences lies in their reproductive organs: ferns do not produce cones. Instead, this feature is exclusive to coniferous trees like pines, spruces, and firs. Cones are the seed-bearing structures of these trees, designed to protect and disperse their offspring. Ferns, on the other hand, rely on spores for reproduction, a process that is entirely different from the seed-based system of conifers. Understanding this distinction is key to appreciating the diversity of plant life and the unique adaptations each group has evolved.

To grasp why ferns lack cones, consider their life cycle. Ferns reproduce via spores, which are produced in structures called sporangia, typically found on the undersides of their fronds. These spores are incredibly lightweight and can be carried by wind over long distances, allowing ferns to colonize new areas efficiently. In contrast, coniferous trees produce seeds within cones, which are heavier and often rely on animals or gravity for dispersal. This fundamental difference in reproductive strategy reflects the distinct ecological niches these plants occupy. While cones provide protection and a mechanism for seed dispersal in conifers, ferns thrive with their spore-based system, which is well-suited to their environments, often shaded and moist habitats.

From a practical standpoint, identifying whether a plant produces cones or spores can help gardeners and botanists determine its care needs. For instance, ferns prefer indirect light and consistently moist soil, conditions that mimic their natural habitats. Coniferous trees, however, typically require full sun and well-drained soil to support their larger size and seed-producing structures. Knowing that ferns do not produce cones eliminates confusion when selecting plants for specific landscaping purposes. For example, if you’re designing a shaded garden, ferns are an excellent choice, while conifers are better suited for sunny areas where their cones can develop fully.

A comparative analysis highlights the evolutionary advantages of both systems. Cones, with their protective scales and seeds, are well-adapted for survival in harsher environments, such as cold or dry climates. Ferns, with their spore-based reproduction, excel in stable, humid environments where spores can germinate readily. This divergence in reproductive strategies underscores the principle of adaptation in biology: each organism evolves traits that best suit its environment. For enthusiasts and educators, this comparison offers a rich opportunity to explore how plants have diversified over millions of years, each developing unique solutions to the challenges of survival and reproduction.

In conclusion, while ferns and coniferous trees share a place in the plant kingdom, their reproductive structures—spores versus cones—highlight their distinct evolutionary paths. Ferns’ reliance on spores for reproduction contrasts sharply with the cone-producing conifers, a feature that is not only biologically significant but also practically useful for identification and cultivation. By understanding these differences, we gain deeper insight into the natural world and can better appreciate the intricate ways plants have adapted to thrive in their environments.

Effective Milky Spore Application: A Step-by-Step Guide for Lawn Grub Control

You may want to see also

Rhizoids in Ferns: Ferns have rhizoids, which anchor them and absorb water and nutrients in gametophytes

Ferns, unlike seed-producing plants, rely on rhizoids for essential functions during their gametophyte stage. These thread-like structures, though often overlooked, play a critical role in the fern life cycle. Rhizoids act as anchors, securing the delicate gametophyte to the substrate, preventing it from being washed away in moist environments where ferns typically thrive. This anchoring function is particularly vital for the survival of the gametophyte, which is the sexual phase of the fern's life cycle and is responsible for producing the next generation.

Beyond their structural role, rhizoids are also the primary means by which fern gametophytes absorb water and nutrients from their surroundings. Unlike roots in more complex plants, rhizoids lack vascular tissue, but they efficiently draw in moisture and essential minerals through a process of osmosis and diffusion. This ability is crucial in the often nutrient-poor habitats where ferns grow, such as forest floors or rocky outcrops. For gardeners cultivating ferns, ensuring that the growing medium remains consistently moist can enhance the effectiveness of rhizoids, promoting healthier gametophytes and, ultimately, more robust sporophytes.

A comparative analysis highlights the uniqueness of rhizoids in ferns. While mosses also possess rhizoids, their function is primarily anchoring, as mosses absorb water and nutrients directly through their leaf-like structures. In contrast, fern rhizoids serve a dual purpose, combining both anchoring and absorptive functions. This distinction underscores the adaptability of ferns, which bridge the gap between simpler bryophytes and more complex vascular plants. Understanding this difference can aid educators in explaining plant evolution and the diversity of plant structures to students.

For those interested in observing rhizoids firsthand, a simple experiment can be conducted. Collect a mature fern frond with spores on its underside and place it on a damp paper towel in a sealed container. Over time, the spores will germinate into gametophytes, and under magnification, the rhizoids will become visible as tiny, hair-like projections. This hands-on approach not only illustrates the role of rhizoids but also provides a deeper appreciation for the intricate biology of ferns. Whether for educational purposes or personal curiosity, this activity offers a tangible connection to the often unseen world of plant reproduction.

Can Filtration Effectively Eliminate Spores? Exploring Methods and Limitations

You may want to see also

Spores in Ferns: Ferns reproduce via spores, tiny structures released from the undersides of their fronds

Ferns, unlike their cone-bearing cousins in the plant kingdom, rely on a fascinating method of reproduction: spores. These microscopic structures, often likened to tiny seeds, are the key to a fern's lifecycle. Released from the undersides of their fronds, spores are the fern's answer to survival and propagation. This unique reproductive strategy sets ferns apart, offering a glimpse into the diversity of plant reproduction.

The Spore's Journey: A Life Cycle Unveiled

Imagine a fern's life beginning with a single spore, so small it's almost invisible to the naked eye. When released, these spores embark on a journey, carried by the wind to new locations. Upon landing in a suitable environment, a spore germinates, giving rise to a tiny, heart-shaped structure called a prothallus. This delicate, flat organism is the fern's intermediate stage, a bridge between spore and mature plant. The prothallus is a self-sustaining entity, capable of photosynthesis, but its primary role is to facilitate the next phase of the fern's life cycle.

Reproduction and Dispersal: A Strategic Approach

Ferns employ a clever strategy for reproduction. The prothallus produces both male and female reproductive cells. When water is present, the male cells swim to the female cells, a process known as fertilization. This results in the growth of a new fern plant from the prothallus. The young fern, now a sporophyte, will eventually develop the familiar fronds we associate with ferns. As the sporophyte matures, it produces spores on the undersides of its fronds, completing the cycle. This method ensures ferns can colonize new areas, as spores are easily dispersed by wind, water, or even animals.

A Comparative Advantage: Spores vs. Seeds

In the plant world, ferns' use of spores is a distinct advantage. Unlike seeds, which require specific conditions to germinate, spores are resilient and can survive in various environments. This adaptability allows ferns to thrive in diverse habitats, from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands. The spore's small size and lightweight nature enable long-distance travel, ensuring ferns can establish themselves in new territories. This reproductive strategy has been key to ferns' success, with over 10,000 species identified worldwide, each with its unique spore characteristics.

Practical Insights: Observing Fern Spores

For enthusiasts and botanists alike, observing fern spores can be a rewarding experience. To witness this process, one can carefully examine the undersides of mature fern fronds, often revealing clusters of spore cases called sporangia. These structures, arranged in patterns unique to each fern species, release spores when mature. Collecting and examining spores under a microscope unveils their intricate shapes and structures, offering a glimpse into the fern's reproductive secrets. This hands-on approach provides a deeper understanding of ferns' ancient and successful reproductive strategy.

Can Mold Spores Penetrate Plastic? Uncovering the Truth and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Seeds in Ferns: Ferns lack seeds; they rely on spores for asexual reproduction and dispersal

Ferns, unlike their cone-bearing counterparts in the plant kingdom, do not produce seeds. This fundamental distinction sets them apart from gymnosperms and angiosperms, which rely on seeds for reproduction. Instead, ferns have evolved a unique reproductive strategy centered around spores. These microscopic, single-celled structures are the lifeblood of fern propagation, enabling them to thrive in diverse environments without the need for seeds. Understanding this mechanism not only highlights the adaptability of ferns but also underscores the diversity of reproductive strategies in the plant world.

The absence of seeds in ferns is closely tied to their life cycle, which alternates between a sporophyte (spore-producing) and gametophyte (gamete-producing) phase. Spores, produced in structures called sporangia on the underside of fern fronds, are dispersed through wind or water. Once a spore lands in a suitable environment, it germinates into a small, heart-shaped gametophyte known as a prothallus. This delicate structure, often no larger than a thumbnail, is where fertilization occurs. The prothallus produces both sperm and eggs, and when conditions are right, sperm swim to the egg, initiating the development of a new sporophyte. This asexual-to-sexual cycle ensures genetic diversity while bypassing the need for seeds.

From a practical standpoint, the spore-based reproduction of ferns offers both advantages and challenges for gardeners and enthusiasts. Spores are lightweight and easily dispersed, allowing ferns to colonize new areas rapidly. However, their tiny size and specific germination requirements—such as consistent moisture and indirect light—can make cultivation tricky. For successful spore propagation, consider creating a humid environment, such as a sealed container with a moist substrate, and maintaining temperatures between 68°F and 75°F. Patience is key, as spore-to-sporophyte development can take several months.

Comparatively, the seedless nature of ferns contrasts sharply with seed-bearing plants, which often rely on animals or wind for seed dispersal. While seeds provide a protective casing and nutrient reserve for the developing embryo, spores offer ferns a different kind of resilience. Their small size and ability to remain dormant for extended periods allow ferns to survive harsh conditions, from droughts to frosts. This adaptability has enabled ferns to persist for over 360 million years, making them one of the oldest plant groups on Earth.

In conclusion, the absence of seeds in ferns is not a limitation but a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. By relying on spores for asexual reproduction and dispersal, ferns have carved out a niche in ecosystems worldwide. For those looking to cultivate ferns, understanding their spore-based life cycle is essential. With the right conditions and a bit of patience, anyone can witness the fascinating journey from spore to sporophyte, gaining a deeper appreciation for these ancient plants.

Why You Can't Control Villagers in Spore: Understanding the Limitations

You may want to see also

Fern Life Cycle: Ferns alternate between sporophyte and gametophyte generations, using spores for propagation

Ferns, unlike seed-producing plants, rely on an intricate dance between two distinct generations: the sporophyte and gametophyte. This alternation of generations is a cornerstone of their life cycle, a process that ensures their survival and propagation without the need for cones, seeds, or even true roots. Instead, ferns utilize spores, tiny reproductive units that are both lightweight and resilient, allowing them to disperse over vast distances through wind or water. This method of reproduction is not just a biological curiosity but a highly efficient strategy that has sustained ferns for over 360 million years.

To understand this cycle, imagine a mature fern plant, the sporophyte generation, which is what most people recognize as a fern. This plant produces spores in structures called sporangia, typically found on the undersides of the fronds. When conditions are right, these spores are released and dispersed. Each spore, upon landing in a suitable environment—moist, shaded, and rich in organic matter—germinates into a gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure often no larger than a thumbnail. This gametophyte is the sexual phase of the fern’s life cycle, producing both sperm and eggs. Unlike the sporophyte, the gametophyte is short-lived and dependent on moisture to facilitate fertilization.

Fertilization occurs when sperm, released from the gametophyte, swim through a thin film of water to reach an egg. This process results in the formation of a new sporophyte, which grows directly from the gametophyte. Over time, the young sporophyte develops into a mature fern, completing the cycle. This alternation between generations is not just a quirk of evolution but a testament to the fern’s adaptability. By separating the two phases, ferns maximize their reproductive efficiency: the sporophyte is robust and long-lived, while the gametophyte is specialized for sexual reproduction under specific conditions.

Practical observation of this cycle can be a rewarding experience for gardeners or nature enthusiasts. To witness the gametophyte stage, collect spores from a mature fern by placing a sheet of paper under a fertile frond and gently tapping it. Sow these spores on a sterile, moist growing medium, such as a mix of peat and perlite, kept in a humid environment. Within a few weeks, you’ll see the tiny, green gametophytes emerge. Ensure the medium remains damp, as dryness will halt their development. For those interested in cultivating ferns, understanding this cycle is crucial, as it highlights the importance of moisture and shade in their care.

In contrast to plants that produce seeds or cones, ferns’ reliance on spores and their dual-generation life cycle offers a fascinating glimpse into the diversity of plant reproduction. This system, while complex, is remarkably effective, enabling ferns to thrive in environments ranging from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands. By studying this cycle, we not only gain insight into the biology of ferns but also appreciate the ingenuity of nature’s solutions to the challenges of survival and propagation. Whether you’re a botanist, a gardener, or simply a curious observer, the fern’s life cycle is a story worth exploring.

Mastering Circle of Spores: Effective Use in D&D Campaigns

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, ferns do not have cones. Cones are typically found in coniferous plants like pines and spruces, which are seed-producing plants. Ferns reproduce differently, primarily through spores.

Yes, ferns have rhizoids, but only in their gametophyte stage (the small, heart-shaped structure that grows from a spore). Rhizoids in ferns are simple, root-like structures that anchor the gametophyte and absorb water and nutrients.

Yes, ferns produce spores as their primary method of reproduction. Spores are found on the undersides of mature fern fronds in structures called sori. These spores develop into gametophytes, which then produce the next generation of ferns.

No, ferns do not produce seeds. They are non-seed plants (vascular plants that reproduce via spores). Seed-producing plants, like flowering plants and conifers, belong to a different group called spermatophytes.

![Greenwood Nursery: Live Perennial Plants - Gaura 'Whirling Butterflies' + Oenothera lindheimeri - [Qty: 2X Pint Pots] - (Click for Other Available Plants/Quantities)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71TyKNqhxAL._AC_UY218_.jpg)