Fungi are a diverse group of organisms that play crucial roles in ecosystems, from decomposing organic matter to forming symbiotic relationships with plants. One of the most distinctive features of fungi is their reproductive strategy, which often involves the production of spores. Spores are microscopic, single-celled or multicellular structures that serve as a means of dispersal and survival in adverse conditions. Unlike plants and animals, fungi do not produce seeds; instead, they rely on spores to propagate and colonize new environments. These spores can be produced in various ways, depending on the fungal species, and are typically released into the air, water, or soil, where they can germinate under favorable conditions. Understanding whether fungi have spores is fundamental to grasping their life cycle, ecological significance, and impact on human activities, such as agriculture and medicine.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do Fungi Have Spores? | Yes |

| Types of Spores | Sexual (e.g., zygospores, ascospores, basidiospores) and Asexual (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores, zoospores) |

| Function of Spores | Reproduction, dispersal, and survival in adverse conditions |

| Structure | Typically single-celled, lightweight, and often encased in a protective wall |

| Dispersal Methods | Wind, water, animals, or explosive mechanisms (e.g., in puffballs) |

| Dormancy | Can remain dormant for extended periods until favorable conditions arise |

| Examples of Spore-Producing Fungi | Mushrooms, molds, yeasts, and rusts |

| Role in Ecosystem | Key role in nutrient cycling, decomposition, and symbiotic relationships |

| Human Impact | Used in food (e.g., mushrooms), medicine (e.g., penicillin), and biotechnology |

| Pathogenic Potential | Some fungal spores can cause diseases in plants, animals, and humans |

Explore related products

$24.99 $24.99

What You'll Learn

- Fungal spore types: Fungi produce diverse spores like ascospores, basidiospores, conidia, and zygospores for reproduction

- Spore dispersal methods: Fungi use wind, water, animals, and explosive mechanisms to spread their spores effectively

- Role of spores in survival: Spores help fungi survive harsh conditions, such as drought, heat, and nutrient scarcity

- Spore formation process: Spores develop through meiosis or mitosis, depending on the fungal life cycle stage

- Comparison to plant spores: Fungal spores differ from plant spores in structure, function, and reproductive strategies

Fungal spore types: Fungi produce diverse spores like ascospores, basidiospores, conidia, and zygospores for reproduction

Fungi are masters of reproduction, employing a variety of spore types to ensure their survival and dispersal. Among these, ascospores, basidiospores, conidia, and zygospores stand out as the most prominent. Each type is uniquely adapted to the fungus's lifestyle and environment, showcasing the remarkable diversity of fungal reproductive strategies.

Ascospores, produced within sac-like structures called asci, are a hallmark of the Ascomycota phylum, one of the largest groups of fungi. These spores are typically haploid and formed through a process called meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity. For example, the common baker’s yeast *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* releases ascospores that can withstand harsh conditions, allowing it to persist in diverse habitats. Gardeners and farmers should note that ascospores of *Botrytis cinerea*, the causal agent of gray mold, can remain dormant in soil for years, making crop rotation essential to manage this pathogen.

In contrast, basidiospores are the reproductive units of Basidiomycota, another major fungal group. These spores develop on club-shaped structures called basidia and are often ejected into the air, facilitating wind dispersal. Mushrooms like the iconic *Agaricus bisporus* (button mushroom) release millions of basidiospores, each capable of germinating into a new fungus under favorable conditions. For foragers, understanding basidiospore dispersal is crucial, as it influences the distribution of edible mushrooms in forests.

Conidia represent a different reproductive approach, as they are asexual spores produced by fungi in the phyla Ascomycota and Deuteromycota. Unlike ascospores and basidiospores, conidia are formed through mitosis, resulting in genetically identical offspring. This rapid reproduction method allows fungi like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* to colonize new environments quickly. However, conidia’s lack of genetic diversity can be a double-edged sword, making fungal populations vulnerable to environmental changes. Homeowners dealing with mold should be aware that conidia from *Cladosporium* and *Alternaria* are common indoor allergens, necessitating proper ventilation and humidity control.

Finally, zygospores are the product of sexual reproduction in Zygomycota, a group of fungi that includes black bread mold (*Rhizopus stolonifer*). These thick-walled spores form when two compatible hyphae fuse, creating a zygospore that can remain dormant for extended periods. While less common than other spore types, zygospores highlight the importance of sexual reproduction in fungal survival. For food preservation, understanding zygospore formation is key, as *Rhizopus* can spoil fruits and bread, especially in warm, humid conditions.

In summary, the diversity of fungal spores—ascospores, basidiospores, conidia, and zygospores—reflects the adaptability and resilience of fungi. Each spore type serves a specific ecological role, from genetic diversity to rapid colonization. Whether you’re a gardener, forager, homeowner, or food enthusiast, recognizing these spore types can help you manage fungal interactions effectively.

Microbe Spores and ATP Readings: Unraveling the Detection Mystery

You may want to see also

Spore dispersal methods: Fungi use wind, water, animals, and explosive mechanisms to spread their spores effectively

Fungi are masters of dispersal, employing a diverse arsenal of strategies to ensure their spores travel far and wide. Among these, wind dispersal is perhaps the most ubiquitous. Lightweight spores, often equipped with structures like wings or hairs, are carried aloft by the slightest breeze. For instance, the common puffball fungus releases clouds of spores when disturbed, each capable of drifting kilometers before settling in a new habitat. This method, while reliant on chance, is remarkably effective due to its sheer scale—a single mushroom can produce billions of spores, ensuring at least some find fertile ground.

Water, too, plays a pivotal role in spore dispersal, particularly for fungi inhabiting aquatic or damp environments. Some species, like those in the genus *Coprinus*, release spores into water currents, which carry them to new locations. Others, such as certain molds, produce spores that are hydrophobic, allowing them to float on water surfaces until they reach a suitable substrate. This method is especially advantageous in ecosystems like wetlands or rainforests, where water is a constant presence. For gardeners or farmers dealing with water-dispersed fungi, managing irrigation and drainage can mitigate unwanted fungal growth.

Animals, both large and small, are unwitting accomplices in fungal spore dispersal. Spores often adhere to fur, feathers, or even the exoskeletons of insects, hitching a ride to new locations. The fly agaric mushroom (*Amanita muscaria*), for example, produces sticky spores that attach to insects, which then transport them to fresh habitats. Similarly, larger animals like deer or birds can carry spores on their coats or in their digestive systems, depositing them in their droppings. This symbiotic relationship highlights the ingenuity of fungi in leveraging existing ecosystems for their survival.

Perhaps the most dramatic method of spore dispersal is the explosive mechanism employed by certain fungi. The aptly named "gunpowder fungus" (*Peziza*) ejects spores at high speeds, propelled by the sudden release of stored energy. This method ensures spores are launched into the air with precision, increasing the likelihood of long-distance travel. While less common than wind or water dispersal, explosive mechanisms demonstrate the evolutionary sophistication of fungi. For enthusiasts studying these fungi, observing this process under a microscope reveals the intricate mechanics behind this natural phenomenon.

Each dispersal method underscores the adaptability of fungi, ensuring their survival across diverse environments. Whether through the gentle waft of wind, the steady flow of water, the unwitting aid of animals, or the dramatic burst of explosive force, fungi have perfected the art of spreading their spores. Understanding these mechanisms not only sheds light on fungal biology but also offers practical insights for managing fungal growth in agriculture, forestry, and even indoor spaces. By recognizing these strategies, we can better appreciate—and control—the pervasive presence of fungi in our world.

Purple Spore Prints: Are Any Poisonous Mushrooms Hiding in This Hue?

You may want to see also

Role of spores in survival: Spores help fungi survive harsh conditions, such as drought, heat, and nutrient scarcity

Fungi, unlike animals and plants, lack the ability to relocate when their environment becomes inhospitable. Instead, they rely on a remarkable survival mechanism: spores. These microscopic, single-celled structures are the fungi’s answer to adversity, enabling them to endure conditions that would otherwise be lethal. When faced with drought, extreme heat, or nutrient scarcity, fungi produce spores as a means of persistence. These spores are not just passive survivors; they are highly specialized units designed to withstand desiccation, temperature fluctuations, and prolonged periods without resources. For example, *Aspergillus* spores can remain viable for years in soil, waiting for favorable conditions to germinate and resume growth.

Consider the desert-dwelling fungus *Eurotium*, which thrives in environments where water is scarce. Its spores are encased in a thick, protective cell wall that minimizes water loss and shields against UV radiation. This adaptation allows the fungus to survive in arid conditions where other organisms perish. Similarly, in nutrient-poor environments, fungi like *Penicillium* produce spores that can lie dormant until organic matter becomes available. This ability to "pause" their life cycle ensures that fungi can outlast periods of scarcity, emerging when conditions improve. The key to this survival strategy lies in the spore’s metabolic inactivity, which drastically reduces energy requirements and allows it to persist in a near-indestructible state.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore survival mechanisms has significant implications for industries such as agriculture and food preservation. For instance, fungal spores contaminating crops or stored grains can remain dormant during harvesting and processing, only to germinate later and cause spoilage. To combat this, farmers and food producers use techniques like heat treatment (e.g., pasteurization at 70°C for 10 minutes) or chemical fungicides to eliminate spores. However, some spores, like those of *Talaromyces*, are notoriously resistant to such methods, underscoring the need for innovative solutions. Home gardeners can reduce spore contamination by rotating crops annually and using sterile potting soil, which minimizes the risk of dormant spores reactivating.

Comparatively, fungal spores’ resilience dwarfs that of bacterial endospores, often considered the hardiest microbial survival structures. While bacterial endospores can withstand extreme heat and radiation, fungal spores excel in long-term dormancy and resistance to desiccation. This distinction highlights the evolutionary sophistication of fungal survival strategies. For example, *Cryptococcus* spores can survive in the harsh environment of the human lung, evading immune responses and causing persistent infections. Such examples illustrate the spore’s dual role as both a survival tool and a challenge in medical and industrial settings.

In conclusion, spores are not merely a reproductive feature of fungi but a critical adaptation for survival in harsh environments. Their ability to withstand drought, heat, and nutrient scarcity ensures fungi’s persistence across diverse ecosystems. By studying these mechanisms, we gain insights into combating fungal contamination and appreciating the tenacity of life in extreme conditions. Whether in the desert, a food storage facility, or the human body, fungal spores remind us of nature’s ingenuity in overcoming adversity.

Are Spores Legal in Canada? Understanding the Current Laws and Regulations

You may want to see also

Explore related products

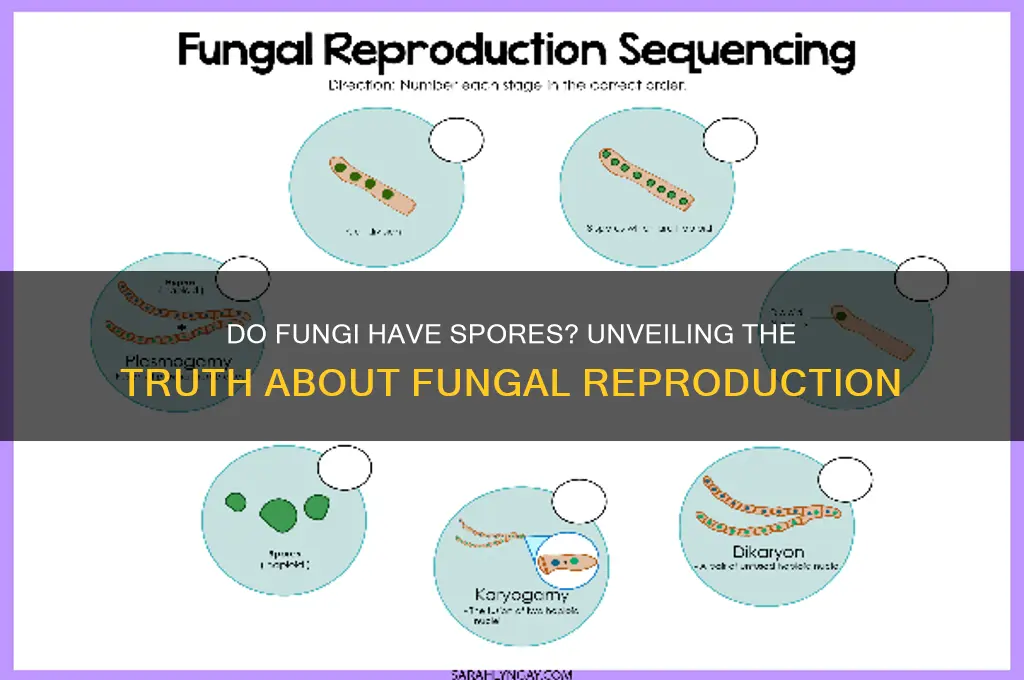

Spore formation process: Spores develop through meiosis or mitosis, depending on the fungal life cycle stage

Fungi reproduce through spores, microscopic units designed for dispersal and survival in diverse environments. The process of spore formation, however, is not uniform across all fungal species. Instead, it hinges on the life cycle stage and the type of fungus in question. At the heart of this process lies the distinction between meiosis and mitosis, two cellular division mechanisms that dictate how spores are produced.

Understanding the Dual Pathways:

In fungi, spore formation occurs via either meiosis or mitosis, depending on the reproductive strategy. Meiosis, a reductive division, is characteristic of sexual reproduction, where genetic diversity is introduced through the fusion of gametes. This process results in haploid spores, such as asci or basidiospores, which are crucial for long-term survival and adaptation. In contrast, mitosis, a replicative division, is employed during asexual reproduction, producing genetically identical spores like conidia or sporangiospores. These spores are ideal for rapid colonization of favorable environments.

Practical Implications of Spore Types:

For gardeners, farmers, or mycologists, understanding these pathways is essential. For instance, asexual spores (mitotic) are more common in molds and yeasts, often causing rapid decay of organic matter or food spoilage. To control such fungi, strategies like reducing humidity or using fungicides targeting mitotic processes can be effective. Conversely, sexual spores (meiotic) are more resilient and can survive harsh conditions, making them harder to eradicate. This knowledge informs practices like crop rotation or soil sterilization to disrupt fungal life cycles.

Comparative Analysis of Efficiency:

Mitosis offers fungi a quick and efficient means of reproduction, enabling them to exploit resources rapidly. However, this method lacks genetic variation, making fungal populations vulnerable to environmental changes or targeted treatments. Meiosis, while slower, ensures genetic diversity, enhancing the species' long-term survival. For example, rust fungi (Pucciniales) alternate between mitotic and meiotic spore production, showcasing a balanced strategy for both proliferation and adaptation.

Takeaway for Application:

Whether managing fungal growth in agriculture or studying fungal ecology, recognizing the spore formation process is key. Mitotic spores require immediate intervention to prevent spread, while meiotic spores demand strategies that address their resilience. By tailoring approaches to the specific reproductive mechanism, one can effectively manage fungal populations and harness their benefits, such as in fermentation or biodegradation. This nuanced understanding transforms spore formation from a biological curiosity into a practical tool for diverse fields.

Does Halo of Spores Affect Multiple Enemies Simultaneously? A Detailed Analysis

You may want to see also

Comparison to plant spores: Fungal spores differ from plant spores in structure, function, and reproductive strategies

Fungal spores and plant spores, while both serving reproductive purposes, exhibit distinct differences in structure, function, and reproductive strategies. Structurally, fungal spores are typically unicellular and lack the complex, multicellular structures found in plant spores, such as the embryo and stored nutrients. For example, fungal spores like those of *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium* are simple, lightweight cells designed for dispersal, whereas plant spores, like those of ferns or mosses, often contain a miniature plant embryo and nutrient reserves to support germination.

Functionally, fungal spores are primarily agents of dispersal and survival, capable of remaining dormant for extended periods until favorable conditions arise. In contrast, plant spores are more immediately focused on germination and growth. Fungal spores, such as those of mushrooms, can be dispersed over vast distances via wind or water, while plant spores often rely on localized dispersal mechanisms, like the bursting of sporangia in ferns. This difference highlights the adaptability of fungi to diverse and often harsh environments, compared to the more habitat-specific requirements of plants.

Reproductively, fungi employ a broader range of strategies than plants. Fungi can reproduce both sexually and asexually through spores, with some species alternating between these methods depending on environmental conditions. For instance, the fungus *Neurospora* produces asexual spores (conidia) under normal conditions but switches to sexual spores (ascospores) in response to stress. Plants, on the other hand, typically follow a more rigid reproductive cycle, with spores playing a specific role in alternation of generations, such as the transition from sporophyte to gametophyte in ferns.

Practical considerations underscore these differences. For gardeners or farmers, understanding fungal spores’ resilience and dispersal mechanisms is crucial for managing fungal diseases, such as powdery mildew or rust. Fungal spores can survive on crop debris or in soil for years, necessitating practices like crop rotation or fungicide application. In contrast, managing plant spores often involves creating optimal conditions for germination, such as maintaining moisture levels for moss or fern spores. This distinction highlights the need for tailored approaches when dealing with fungal versus plant reproductive structures.

In summary, while both fungal and plant spores serve reproductive functions, their differences in structure, function, and strategy reflect distinct evolutionary adaptations. Fungal spores prioritize dispersal and survival, with versatile reproductive methods, whereas plant spores focus on immediate germination and growth within specific habitats. Recognizing these differences is essential for fields ranging from agriculture to ecology, enabling more effective management and appreciation of these diverse organisms.

Do Coliforms Form Spores? Unraveling Their Survival Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, all fungi produce spores as part of their reproductive cycle, though the type and method of spore production vary among different fungal species.

Fungi release spores through various mechanisms, such as bursting spore-containing structures (like sporangia or asci), wind dispersal, water currents, or even by being carried by animals.

Fungal spores serve as a means of reproduction and dispersal, allowing fungi to survive harsh conditions, colonize new environments, and spread to new locations.